PRESENCE OF MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS

06/02/2012

LOCATION

31/03/2012“The right to development of the indigenous peoples brings with it the right to determine their own rhythm of change, in accordance with their own vision of development. This right also implies the ability to say no to large projects that seriously affect their lives.“

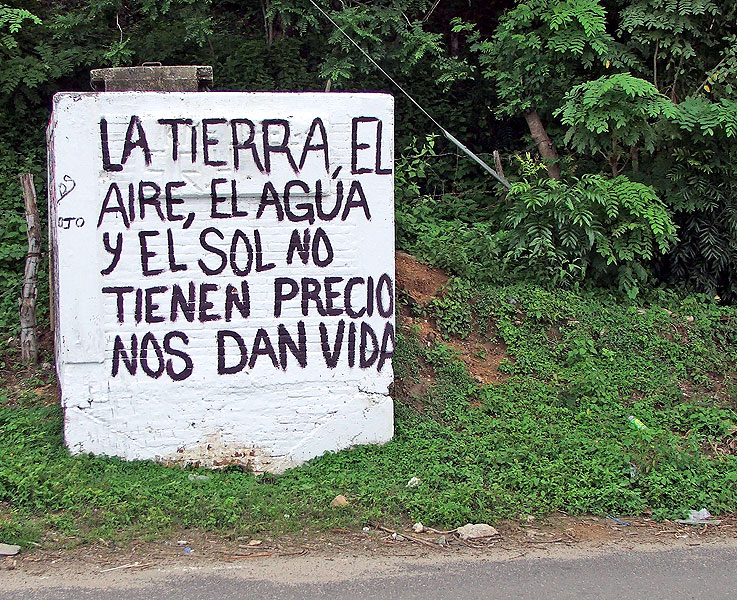

Throughout Latin America, indigenous, civil, and social organizations have denounced the intervention of national and transnational firms in the lands of indigenous peoples. They shield themselves with the term “development” as the promotion of economic and social activity of a country, while the interest of these firms has translated into the maximum exploitation of natural resources, a reality that has devastated nature and dismantled forms of life and cultures based on ancestral traditions.

At a certain point, multilateral platforms saw it necessary to regulate the form and means of development that each people or community would like to apply, because it is not a question of the indigenous populations not wanting to live better or have better living conditions, but rather that they be able to do so in their own ways, on their own time, and in a fashion that most aids future generations to grant them a better future. What many have called the self-determination of indigenous peoples that will allow the Tsotsils and Tseltals of Chiapas the space to live life to the fullest by their standards, as summarized in their lekil kuxlejal, or the harmonious integration of the individual, society, and nature.

At the margin of questioning the idea of development for some and not others, the problem that many indigenous populations suffer is based on the fact that their territories, lands, or sacred spaces are the sources of rich natural resources that are very desirable for the private sector and the powers that regulate it. Water, mountains, and forests are seen as perfect scenery for dams, mines, highways, and eco-tourist centers, among other mega projects. Zones that previously were forgotten now are seen to be strategic in the eyes of the neo-liberal market.

In the idea of the right to consultation is stressed the importance to recognize indigenous peoples as the legitimate actors to take decisions regarding their own destiny. It is a practical and concrete expression of their more general right to self-determination. It is not the State or any other existing power that must determine what is best for the development of peoples and communities. It is a mechanism capable of overturning the historical exclusion of indigenous peoples from decision-making spaces and also of avoiding the imposition of schemes from the past.

International mechanisms regarding consultation and indigenous rights

The progress in the debate on the rights of indigenous peoples and in particular the question of the right to consultation and prior informed consent have been translated into the elaboration of various international conventions. These assert that the right to consultation should be considered principally collective, as a mechanism that peoples and communities use to defend other collective rights, such as their right to cultural identity, land, territory, and natural resources, to conserve their normative institutions and systems, and in extreme cases their right to survival as people. To assure the participation of indigenous peoples, the State has the obligation to actively consult with a given community according to their customs, to supply information, and to promote constant communication between the parties, without aim to trick or betray them or provide them misleading or partial information. Consultation processes, as well as the decision of the peoples that these allow for, should not merely be considered formalities.

In this sense, governments have the responsibility to guarantee the carrying out of studies on social and environmental impacts in coordination with indigenous peoples, toward the end of evaluating social, spiritual, cultural, and environmental risks. The results should be fundamental criteria for the carrying out or rejection of development projects.

In 1990 the Mexican State ratified Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), one of the oldest instruments that most specifically recognizes and protects the rights of indigenous peoples, especially the right to consultation, given that this establishes that indigenous peoples should participate effectively in the decision-making processes that could affect their rights and interests.

The 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, signed by Mexico in 2009, is another international mechanism addressing the rights of indigenous peoples. Concretely, article 19 indicates that “States will carry out consultations and cooperate in good faith with interested indigenous peoples […] before adopting and applying legislative or administrative measures that could affect them, toward the end of obtaining their prior informed consent.”

The absence of prior informed consent can generate violent contexts of division

Consultation should be prior to implementation—that is to say, “before undertaking or authorizing whatever program of exploration or exploitation of given resources in a given territory” (Convention 169). In many cases, when indigenous peoples were not previously informed and decided to oppose themselves to projects, they often confront violent contexts due to lack of protection by public-security units or indeed precisely from these institutions. In 2006 the Canadian company Fortuna Silver arrived in San José del Progreso, Oaxaca; this firm operates through its Mexican subsidiary Cuzcatlán, given that this company obtained permission from local authorities for their extractive project while the rest of the community had not been informed. Since then, the sector of the community that has opposed itself to the mine has been victimized by constant aggressions, death-threats, arbitrary detentions, and criminalization of protest. In March 2009, residents affected by the firm decided to block access to the mine to demand that permits and authorizations for exploratory operations be re-examined, and this was met with a joint police-military operation. The community suffers profound internal divisions, and their rights to consultation and consent continue to be violated while the mining company continues with its work. On 18 January a member of the Coordination of United Peoples of the Ocotlán Valley (CPUVO) was killed. He was fired on presumably by police and members of the municipality when he was protesting the installation on his land of tubes that would permit water-exploitation by the mining company. The permit for this was granted by the municipal authorities without having consulted the people. The conflict continues worsening. It could potentially end in a social explosion by the residents.

Information and regression

The true exercise of the right to consultation demands that it be carried out free of coercion, intimidation, or manipulation. Indeed, the forced choice of either to develop oneself or continue in poverty and marginalization also could be considered a form of coercion regarding the decisions of indigenous peoples. Similarly, as stipulated in international law, the people should enjoy sufficient information to permit them to take a position with respect to the project. If there existed some problem or if this violated one of the principles in a true consultation process, the communities and peoples would have the right to repudiate the decision that has authorized the project. In the case of the community of San Dionisio del Mar, in the Tehuantepec Isthmus, Oaxaca, an assembly was held last January among “shared land owners” (comuneros) that analyzed the conditions under which a contract of usage had been signed with the Preneal firm in 2004. They denounce that “the “shared land owners” (comuneros) were not informed of the extent and significance of the wind project in the territory of the Ikojts people.” For this reason, they agreed unanimously to revoke the contract with said company “for its being a contract signed in duplicity and bad faith, toward the end of obtaining economic benefits, taking advantage of our ignorance of national and international law. For these reasons our right as indigenous people to full, sufficient, and adequate information was violated.” The conflict in the community began on 29 January, when the mayor reported the authorization of the permits of change of surface-use for the wind project that the Macquaire (formerly Preneal) firm would like to construct in the community of Pueblo Viejo. The “shared land owners” (comuneros) accuse the mayor of having received 17 million pesos for this. To protest, residents took city hall.

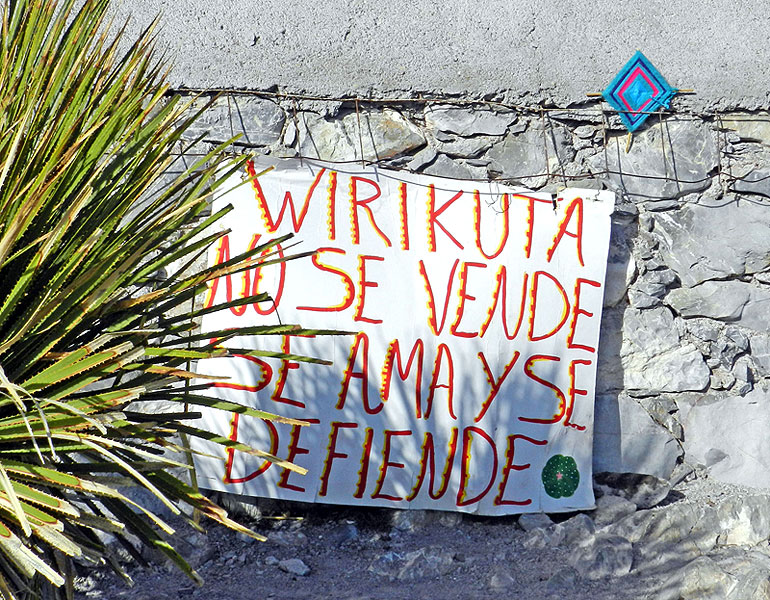

Culture and environment: symbols for indigenous peoples

On occasions, the places most profitable for economic exploitation contain important cultural or spiritual significance for the traditions and cosmovisions of indigenous peoples. Clearly, the maintenance of these zones in environmental and public-health terms is a primordial resource for those people affected by these projects. One example is Wirikuta, a sacred space and pilgrimage route for the Wixárika people in San Luis Potosí, where the Mexican government awarded 22 mining concessions to the Canadian firm First Majestic Silver Corp. and its Mexican counterparts, Minera Real Bonanza and Minera Real de Catorce without consultation. Tunuary Chávez, responsible for environmental analysis and forest management for the Jalisco Association of Support for Indigenous Peoples (AJAGI) affirms that “Pollution by heavy metals is permanent, and to eliminate it is practically impossible once these metals have entered the food chain. Such contamination is persistent and irreversible, and this is now clear in Wirikuta.” Despite the fact that in 2008 the Mexican government signed a pact to respect, protect, and preserve the sacred sites of the Huichol people, mining concessions continue, and so do denunciations regarding the lack of studies into environmental impact and the violation of the state decree of the Wirikuta Natural Protected Area and Ecological Reserve.

When the opposition delays projects

Organizations such as the Project for Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ProDESC) have identified that transnational companies foment divisions among affected communities, in collaboration with orders from the government. Rosalía Márquez García, member of ProDESC, affirms that “the Mexican government omits its obligation to inform and consult communities and owners of lands.” In Chiapas in 2009, there was announced the highway project between San Cristóbal de Las Casas and Palenque, the latter city being the site of many communities and spaces of interest for touristy development. It bears contemplating that the planned project would connect with the Palenque international airport and affect 70 kilometers of the so-called Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, including the Agua Azul waterfalls, a tourist site that is even more important than the archaeological zone at Palenque. The highway, which would measure 21 meters for four lanes with a central divider, would reduce the transit time between the cities to 2 hours. Ejidos such as Mitzitón and San Sebastián Bachajón have spent years resisting the implementation of the project. According to the denunciations of various members of the ejido in Mitzitón, engineers from the Secretary for Communication and Transport (SCT) have determined to date that 10 homes would have to be destroyed, and that croplands and fruit trees would also have to give way—these being the primary modes of production and subsistence for many. Whether the rejection of those that would be affected or by lack of resources to carry it out, the planned highway at the moment finds itself suspended.

Fixed communal assemblies

In cases like that of Guerrero and the hydroelectric dam “La Parota,” the assembly mechanism as a system for consultation continues to be inadequate as regards the stipulations of the ILO’s Convention 169, given that large segments of the populace that would be affected have been excluded. In 2004 the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) carried out technical studies for the construction of said dam, close to Acapulco. Its construction on the Papagayo river would imply the flooding of 13 communities and more than 14,000 hectares, the relocation of more than 25,000 residents, forced to abandon their homes, and would indirectly affect 75,000 other people, in addition to grave environmental consequences. The Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP) is an organization resisting this initiative, which represents 63% of the land that would be affected by the project. Since 2005, several ejidal assemblies have been held to decide whether or not to permit the progression of the project. CECOP turned to legal means to repudiate the assemblies in four communities in which the campesinos supposedly had agreed to the expropriation of the lands. For example, in April 2010, during an assembly called for by communal authorities close to the government, residents of Cacahuatepec approved the expropriation of more than 1,300 hectares of land for the dam. The assembly was overseen by 600 police who refused entry to members of CECOP, and for this reason the organization demanded that the Unitary Agrarian Tribunal (TUA) nullify the results of the assembly—a petition that was accepted a year later. The Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights emphasizes that “with [this resolution] we find FIVE CASES resolved in favor of the “shared land owners” (“comuneros” and “ejidatarios”) opposed to La Parota.” The opposition of the communities and disposition of others to accept the destruction of lands for the construction of the project has divided local populations. These divisions have in turn resulted in recent years in several deaths, grave injuries, and arrests.

In light of “development” projects, why the lack of consultation?

The lack of will to include indigenous populations in consultation processes on the part of the Mexican government seems systematic. One hypothesis for this lack of interest to inform and consult communities is that it would yield negative results for the prosecution of the majority of development projects. Every day more and more investigations by civil and social organizations and university students demonstrate the environmental and social costs that would be borne by the local populations that would be affected would be much greater than the economic and employment benefits that could be experienced if these development projects were to proceed. It would seem that the lack of consultation hides an interest that would continue taking advantage of firms and state authorities, but not the owners of the lands who would remain when the firms disappear, having exploited all possible resources, with all the consequences this would imply. Mina Navarro, professor in the Political and Social Sciences at UNAM, declared in her speech “Mining as a global project” that “Firms do not internalize environmental costs; if they did, they would not be profitable and would not make any money.”

For this reasons numerous processes have been created, social networks, and civil organizations in opposition to mega-projects in the Mexican Republic and most of Latin America. One example of resistance to mining companies is the Communal Police, an organization of peoples of the regions of Costa Chica and Montaña in Guerrero that includes 65 communities and is comprised of the Regional Coordination of Communal Authorities (CRAC-PC). In 2010 and 2011, CRAC began to lead the movement against mining concessions in the area. All the polluted water would be sent to the coast, which would suggest generalized side effects, including for residents of other communities. They initiated the campaign “With open heart, we defend our Mother Earth against mining,” which implies information-reporting oriented above all toward the youth, “because the concessions are for 50 years—that is, they can just hold them there for 30 years and then start to remove things again. In 30 years we will not be here,” noted one of CRAC’s regional coordinators.