2004

03/01/2005

UPDATE: From the Red Alert to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle

29/07/2005In January, during his visit to Chiapas, from the very heart of the “conflict zone,” President Vicente Fox claimed that the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) is an issue that “now essentially remains in the past and everyone sees it going forward.” These statements unleasheda controversy. The COCOPA (Commission for Agreement and Pacification, a legislative body that has facilitated the strained negotiations between the EZLN and the Executive Branch) expressed an “extreme bewilderment,” although not on an official level, due to the lack of a quorum at the emergency session that was called because of these declarations.

Pablo Salazar Mendiguchía, Governor of Chiapas, was somewhat able to mend the unfortunate statement made by Fox, by saying: “I share his point of view that Zapatismo as an armed strategy is a thing of the past. We were speaking about the new expressions of Zapatismo, which are civilian in nature, and efforts within their own territory to provide themselves with new forms of coexistence.”

Many non-government organizations emphasized that the conflict in Chiapas continues unabated in its structural causes (see SIPAZ Website). They affirmed that the strategy of a “war of attrition” currently doesn’t feature direct conflict, but instead focuses on a series of military, political and economic strategies that aim to isolate the Zapatistas while sparking conflicts at the community level. More than anything else, the words of President Fox prove that the EZLN is not the biggest problem of the current government, which already finds itself embroiled in a heated premature struggle for the 2006 presidential elections, cornered by the growing problem of drug trafficking, and with legislative bills still pending, which take greater priority for his administration.

On the other side, the EZLN has maintained a kind of unofficial truce with the authorities on the state level. The group has opted for a strategy of non-confrontation that permits them to continue strengthening their process of constructing autonomy through the pragmatic way of facts (see Focus).

New Conflicts, Old Conflicts

On a state level, a multiplication of different types of conflicts can be seen. On one hand, there has been a reactivation of several peasant organizations, which brings with it a renewed confrontation with the state government. Some of these groups, like the CIOAC (The Independent Central of Farm Workers and Peasants), which once supported governor Pablo Salazar, now have turned their backs on him, questioning the lack of attention given to their demands. Other conflict fronts have come from teachers’ unions and the growing resistance movement against high electricity prices (see previous newsletter).

In addition, the conflict in the Biosphere Reserve in Montes Azules still continues. In January, more than 800 indigenous Tzeltales that had been living in seven communities around Ocosingo were relocated to the settlement of “New Montes Azules,” in the municipality of Palenque. It is worthwhile to highlight that these relocations can create new conflicts that are inter-ethnic in character, by grouping together families that speak different languages in the new settlements. The state continues to skirt the root causes of this problem rather than confronting them directly.

Three other phenomena that, up to now, have corresponded mostly to the border regions are beginning to extend to other regions of the state. They are: the growth of the maras salvatruchas (Salvadoran gangs) and drug trafficking, along with the denouncement of the ever more widespread trend of “femicide.” Chiapas ranks as one of the top five locations in the nation for murders of women.

Another theme of growing concern, from small villages to cities, is migration due to the lack of economic opportunities in the state. The government admitted that during 2004, Chiapas received $500 million in money transfers, the product of the work of thousands of migrants, and a 40% increase over the previous year. It is to be noted that these last three problems are not exclusive to Chiapas, but rather are found throughout the whole Central America.

On the eve of January 1, the date that the new municipal authorities took power after the elections from last October, demonstrations were held, highways were blocked, and confrontations took place in various municipalities (Oxchuc, Tila and Sabanilla, for example).

Tila was the most violent case. In this municipality of the northern zone, the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) won by less than 100 votes over the Alianza PRD-PT (Alliance of the Democratic Revolutionary Party and the Workers’ Party). Both groups announced victory. Due to the lack of agreement, the issue was taken to the corresponding electoral institutions. The highest court, the Electoral Tribunal of Judicial Power of the Federation (TEPJF) declared the PRI, and its candidate Juan José Díaz Solórzano, victorious. Ignorant of this resolution, members of the Alianza PRD-PT staged a sit-in at the municipal palace in late December to prevent the new mayor from taking power. A resolution was sought by allowing Alianza members to participate in municipal court, but they refused since the posts were secondary.

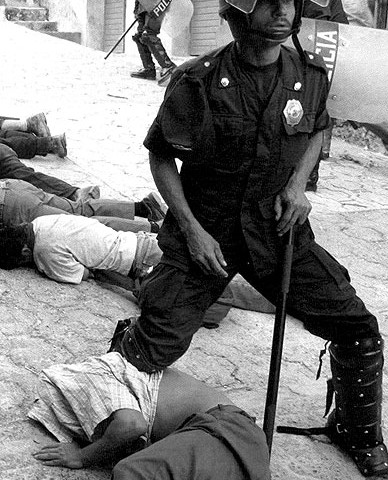

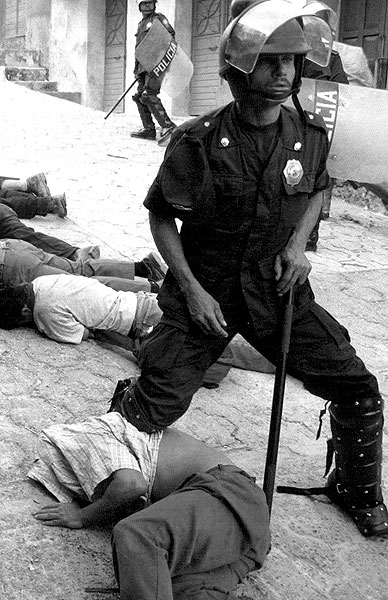

On February 15th, there was a violent dispersal of the sit-in, and around 54 people were arrested, according to the numbers provided by the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center (49 according to official numbers). Six houses were burnt, three cars were destroyed, and highways were blocked intermittently. At least 800 armed members of the Policía Sectorial (Sectorial Police) and the Agencia Estatal de Investigaciones (State Investigations Agency) took part in the action.

The first operation took place in the morning. Members of the Alianza set fire to a few houses and took five people prisoner in order to exchange them for 19 people previously detained by the police (they were released later that day). In the afternoon, a strongly armed police contingent selectively searched a few houses again. Thirty-five more people were arrested. On this day, many Tila inhabitants, mainly Alianza supporters, chose to take refuge in the mountains, in different cities of the area, and even outside Chiapas. On February 28th 30 of those arrested were released; the rest remain in prison.

The parish priest of Tila, Heriberto Cruz, noted that tension in the region had resurfaced due to the post-election conflicts and to the revival of the paramilitary group ‘Paz y Justicia’ (Peace and Justice). He stated that in such a context, the police evictions “reopened the wounds of the indigenous people of Tila” and also “put peace at risk.”

In the days following the evictions, Samuel Sánchez Sánchez, founder and leader of ‘Paz y Justicia’ was arrested. This arrest was described as “late and insufficient” by the Fray Bartolomé Human Rights Center. Currently, Petalcingo, another main city in the Northern Region, is still occupied by police, and more evictions are feared.

All these facts take us back to the question of who actually won the elections. The permanent rotation of candidates between PRI-PRD-PT, so characteristic of the Northern Region, puts in evidence the deep identity crisis in which these political parties are immersed. For example in Tila, the municipal presidency was being disputed by two quarreling factions of ‘Paz y Justicia’. On one side, the PRI is mostly made up of members of UCIAF (a group that split from ‘Paz y Justicia’); on the other, there were also former leaders of ‘Paz y Justicia’ in the PRD-PT Alliance.

Even though the dispute was mainly due to the PRI’s internal struggles, people traditionally linked to the PRD also expressed their disapproval of the PRI candidate. The violent military operation did not take into account this complexity, nor the fragile situation in the Northern Region. The excessive attack by police struck a weak spot: the breaking down of the social fabric.

In order to better understand the context in which this conflict developed, it is useful to review a few issues that some would like to consider no longer relevant. On February 9th the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center made public a complaint about human rights violations in the Northern Region of Chiapas, which had been previously submitted to the Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (Interamerican Human Rights Comission) in October 2004. They delayed in making it public in order to guarantee the safety of the plaintiffs, but the chosen date was not a coincidence.

On February 9, 1995, the government of Ernesto Zedillo launched a military offensive to capture the Zapatista leadership. After this date there was a marked change in the military’s strategy. There was a significant escalation of violence against Zapatistas and the civilian population by paramilitary groups, such as ‘Paz y Justicia,’ which left thousands displaced and dozens murdered or disappeared. The complaint accuses former President Ernesto Zedillo of crimes against humanity in his role as Commander in Chief of the Mexican Armed Forces. It also levies the same charge against General Enrique Cervantes Aguirre, former Secretary of National Defense and General Mario Renán Castillo, former Commander of the Seventh Military Region.

The Fray Bartolomé Human Rights Center specified that, the same as in the Ch’ol region, justice still hasn’t been served in Acteal (December 2004 marked the seventh anniversary of the massacre), among other cases. The group denounced the fact that paramilitary groups have neither disarmed nor disbanded, that those responsible for planning and carrying out the attack remain unpunished, and that no reparations have been made to the victims of forced displacement, murder, disappearances and torture. The Center’s complaint emphasizes that an “invisible war” still continues in Chiapas.

The National Situation is Equally Complex

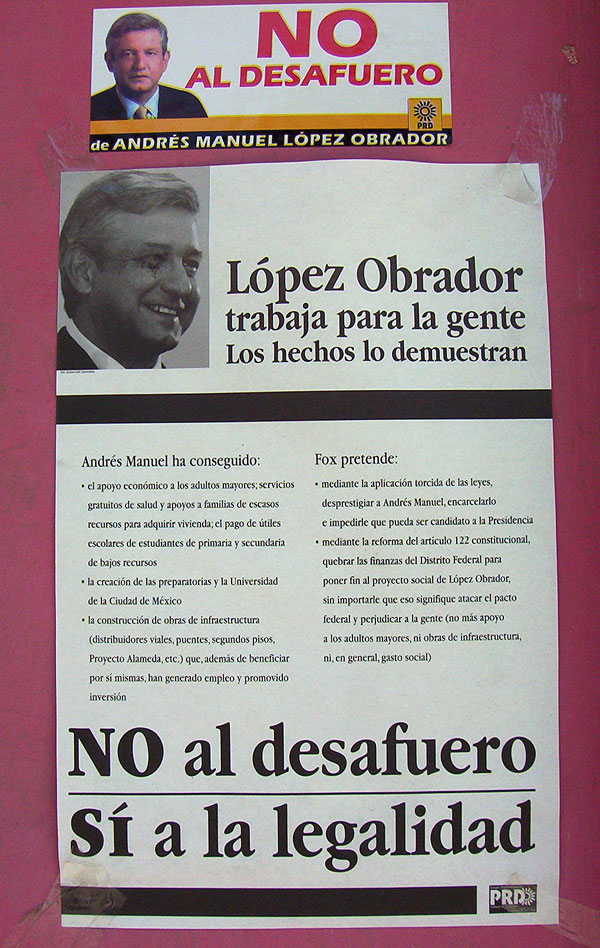

Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s (AMLO) desafuero issue (the attempt to disqualify him from running for president) remains a central matter in the national political debate. It should be known that a request has been made by the Procuraduría General de la República (the Office of the Procurator General of the Republic) to strip AMLO, the mayor of México City, of his right to run for office by prosecuting him for his alleged abuse of power and non-compliance with a court order demanding him to stop the construction of two roads. This could prevent his candidacy. The excessive media coverage of this issue has overwhelmed citizens, which could be part of the strategy. Mexicans are largely against this arbitrary action of the federal government. In the past few months there were several demonstrations and many citizen support committees are still being formed. Regarding attacks from the current President, AMLO himself declaredthat “President Fox is my best campaign manager.”

President Fox and his PAN (National Action Party) Party, when not making accusations against the governor of the capital, limit themselves to issuing messages in favor of “legality.” The PRI has had a certain amount of success in defining the debate, and has taken advantage of the situation to iron out internal differences and strengthen itself through state elections. After regaining ground in the northern states, and with its victories in Veracruz, Oaxaca and Puebla, the PRI is currently in control of the north, east and south of the country. They have cornered the central and western states, which are governed by PAN and the PRD. However, the PRD’s victory in Guerrero opened an important space in the south, a traditional PRI stronghold.

Even the EZLN has joined the debate about the desafuero with an apparently impartial position. After the indigenous reforms of 2001, which was considered a “betrayal” by the EZLN, they broke off communication with political parties. However, the Zapatistas expressed their strong disapproval to the process of desafuero. They emphasized that even though they do not support AMLO or the PRD, they are against the desafuero process since ‘it is not only illegitimate, but also illegal and unfair”, adding that it would be a “pre-emptive coup detach.”

For their part, represantives of Mexican banks, considering a possible victory of the PRD on the presidential elections, stated that a left-wing president would not be a threat for the country’s economy. This statement differs from the one that bankers previously made, when they predicted economic disaster if the presidency was won by a left-wing party.

On the other hand, the last few months have witnessed the tough war waged by drug traffickers against the federal government, with tens of policemen executed in several states around the country. A number of people have been arrested for being suspected of having infiltrated various state agencies,and even Los Pines (residence of the President). The decision made to militarize the high security prison at La Palma, as well as other prisons, due to the infiltration of drug tsars among prison workers.

The US State Department issued its annual report on human rights in México, pointing out serious problems regarding police and army corruption, kidnappings and extortion carried out by state and local policemen, arbitrary arrests, confessions made under torture, and extrajudicial murders committed by cops and army personnel, along with the “poor” state of human rights, especially in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca and Chiapas.

José Luis Soberness, president of the Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (National Human Rights Commission), declared that the US has no moral authority to criticize México on this matter, but recognized that “it is unfortunately true.” However, Condolezza Rice, US Secretary of State, assured during her visit to the country that the White House “is not targeting México.” Referring to the next presidential elections she also declared that the US government would accept any type of government in México “as long as it is within the democratic parameters.”

In late February, the representative of the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights in the country, Anders Kompass, affirmed that México is “the last in the line” of Latin American nations in terms of administration of justice, and urged that legislative and legal frameworks be improved in order to protect the individual constitutional rights of citizens.

Even though the case of Digna Ochoa’s death is already closed, and that of Noel Pavél, is about to be concluded, both still lack justice. In January, replying to the letter written last September by Bernardo Bátiz Vázquez, Attorney General of Mexico City (PGJDF), sub-commander Marcos stated: “What the PGJDF has done, Señor Bátiz, did not uncover the truth nor administer justice. The only thing intended, and achieved, was the gaining of the support of the right wing by discrediting two people who were worth more than all the Mexico City Government workers combined. And it has been done in the most shameful way: by defiling their deaths.” He demanded that the General Attorney reopen the case on Digna and force his officials to behave responsibly, seriously and efficiently in the case of Pavél. For his part, Bátiz approved the conclusion that human rights lawyer Digna Ochoa and Noel Pavél both committed suicide. However, in February, the second court in criminal affairs ordered the PGJDF to reopen the investigation of the death of Digna Ochoa.