© Emma Rodríguez

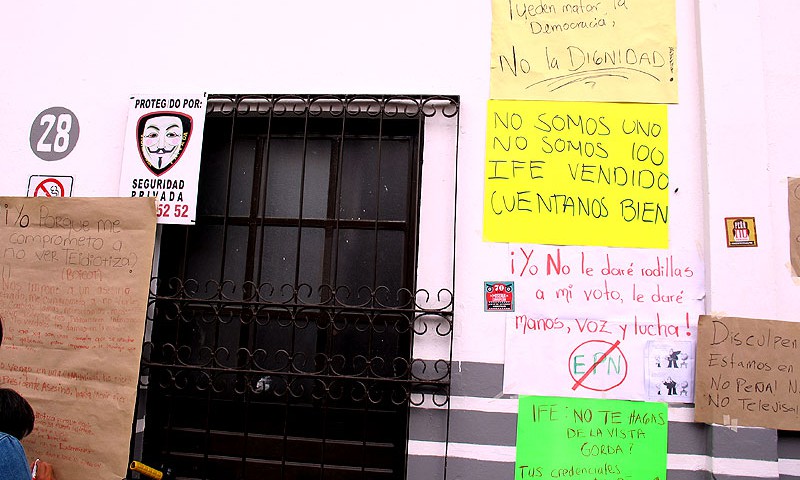

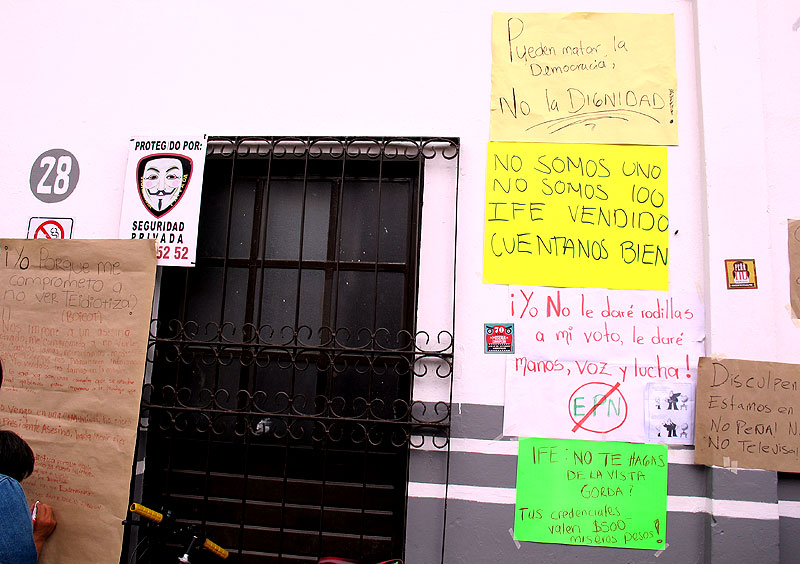

Unsurprisingly, on 31 August, Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN), presidential candidate for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM), received official confirmation accrediting him as president-elect, following the validation of the 1 July electon by the Judicial Electoral Tribunal of the Federation (TEPJF). More surprisingly, if we recall its behavior in the 2006 elections, the TEPJF unanimously rejected all the denunciations made by the left-wing party coalition toward the end of requesting that the election results be nullified. The Progressive Movement had presented 359 challenges indicating the exorbitant spending by the PRI in its campaign, the early promotion of EPN’s candidacy through the Televisa chain, as well as the mass buying and coercion of votes. In accordance with a poll carried out by Covarrubias, only 37% of the population believes that Peña Nieto “cleanly won” these elections.

© kontrakorriente85

Both the Progressive Movement, led by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO, presidential candidate for the leftist parties in the July election), as well as social movements and civil organizations have rejected the decision of the magistrates. Thousands of people took to the streets of Mexico City to protest and surround the TEPJF office. AMLO organized a demonstration on 9 September in the zócalo of the capital city at which he reiterated his refusal to admit defeat, announcing his departure from the Party for Democratic Revolution (PRD) and calling for a decision regarding the creation of a new party to emerge from the Movement for National Regeneration (Morena). Meanwhile, the PRD proposed “a position of respect for law and the legal order.” Subsequently, on 22 and 23 September, 280 organizations and collectives from 20 states, including the youth movement #IAm132, carried out a Second National Convention against Imposition in Oaxaca de Juárez, at which they discussed a plan of action to impede EPN’s taking of power on 1 December.

For his part and without seemingly even acknowledging these challenges, Peña Nieto chose his transition team during the first days of September, while at the same time fleshing out some proposals and actions he hopes to promote upon taking office. He also engaged in an international tour to various Latin American and European countries.

Sixth and final report by Felipe Calderón

Another front of social mobilization emerged in response to the sixth and final report of the government of President Felipe Calderón. The #IAm132 movement presented a counter-report in which it also evaluated the president’s six-year term, “six years in which year by year we have seen a cowardly president speaking of bravery while we citizens of society bury the dead [and tend] to those displaced, kidnapped, and humiliated by the authorities.” In a public act, Calderón affirmed for his part that his behavior was “humanist.” He placed particular emphasis on progress against organized crime, stressing that this struggle “advanced significantly in containing and debilitating criminal organizations.”

Shortly before the release of this report, Amnesty International presented a severe appraisal of the six-year term in terms of security and human rights. “The government of Felipe Calderón put in place a policy of public security to confront groups of organized crime militarily, a strategy that severely aggravated violence in several regions of the country, without having any strategy or capacity to arrest this violence or guarantee security for affected populations. This policy was built upon the routine mass deployment of the Armed Forces in police work, a tendency that created an alarming increase in the number of denunciations of human rights violations committed by public security forces.” In this sense, in October, the National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” released a condemnation of the federal government for “60 thousand deaths, a number that proportionally is larger than those killed in the Guatemalan civil war; more than a thousand disappeared, which exceeds the number similarly affected during the Dirty War; thousands of refugees and people internally displaced by violence; an unprecedented increase in the use of torture as a means of investigation and punishment; attacks on the rights of women, and increasing feminicide.”

…And more mobilizations…

© www.caravanforpeace.org

In other news, these past weeks have seen a great deal of mobilization against the labor reform being discussed in Congress at this time, a proposal that many see as opposing the interests of workers. There are various structural changes that have been proposed even before the new government is inaugurated: labor, fiscal, and energy reforms. Given the composition of the newly elected Congress, the PRI, with the support of PVEM and the Party of New Alliance (Panal), has the majority in the Chamber of Deputies, a reality that will allow it to advance its proposals for at least the coming three years.

Beyond this, on 12 September, the Caravan of the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity (MPJD) concluded its tour through the United States. Although the coverage of the Caravan by U.S. mass media was limited, Javier Sicilia characterized the initiative as a positive one, given that “for the first time, Mexican and U.S. citizens decided to engage in citizens’ diplomacy” in light of the omission by their respective governments. The MPJD met with several U.S. Congresspeople and members of the Executive Branch to demand that they not only stop supporting the war strategy against organized crime by suspending sales of weapons to the Mexican Army, but also that they redouble their efforts to restrict the trafficking of arms and the demand for drugs within U.S. society.

Some advances in terms of human rights, with much more to be done

© zapateando.wordpress.com

In mid-August, the Supreme Court of Justice in the Nation (SCJN) decided to restrict the jurisdiction of military tribunals, declaring that crimes committed by soldiers against civilian populations should not be judged in military courts. This has been a central demand raised by human rights centers, national and international, for several years now. Another significant advance occurred in November with the installation of the “Governmental Council” made up of members of civil society and governmental authorities, which formally launched the mechanism for the protection of human rights defenders and journalists, derived from the Law for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists that was recently approved. The Council’s function will be to observe, monitor, and make effective the protection measures that are to be established.

Nevertheless, it remains clear that Mexico has shortcomings regarding the observance of human rights, particularly in terms of torture, given that in November the United Nations Committee against Torture (CAT) carried out a highly critical evaluation of the Mexican State in these terms (see In Focus). Similarly, in October, the Forum on Migration in Mexico expressed that “during the administration of Felipe Calderón […] corruption, complicity, and impunity have favored atrocious violations of the human rights of migrant populations transiting through Mexico.” The Work Group on Migration Policy for its part has indicated that the rules implementing the Law on Migration, passed on 28 September, reflect some changes, but that “profound problems persist which make vulnerable the rights of migrant persons.” It indicated in particular that “the Rules that were approved leave gaps […] given that they promote selective migration by means of systems of points and quotas, without comprehensively addressing the totality of migratory flows through the national territory. It limits itself to administration, and this without innovating in questions such as alternatives to imprisonment. Nor does it promote progress in terms of the protection of especially vulnerable groups.”

Chiapas: political transition at the national, state, and municipal levels

In parallel to the close of Felipe Calderón’s administration, the administration of the present governor of Chiapas, Juan Sabines Guerrero, will also be coming to a close. Sabines went from being considered a “model student” in terms of human rights to being progressively questioned in recent months, not only in terms of human rights but also due to the indebtedness of the state (it owes slightly more than 20,300,000 pesos). The governor-elect, Manuel Velasco Suárez, will take office at the beginning of December. Similarly in Chiapas, on 30 September, the mayors elected in the July elections took power, a transition that saw several violent acts in Motozintla, Chicomuselo, Bejucal de Ocampo, Frontera Comalapa, Mazapa de Madero, Cintalapa, Tila, and Las Rosas. Another series of conflicts and blockades occurred in protest against the exiting municipal teams of Villacorzo, San Juan Chamula, and Teopisca.

Not unrelatedly, several communal conflicts have worsened in these months, and the exiting state government seems not to be interested in involving itself in these, especially those that have emerged in the Venustiano Carranza and Chicomuselo municipalities among different social organizations, or even within them.

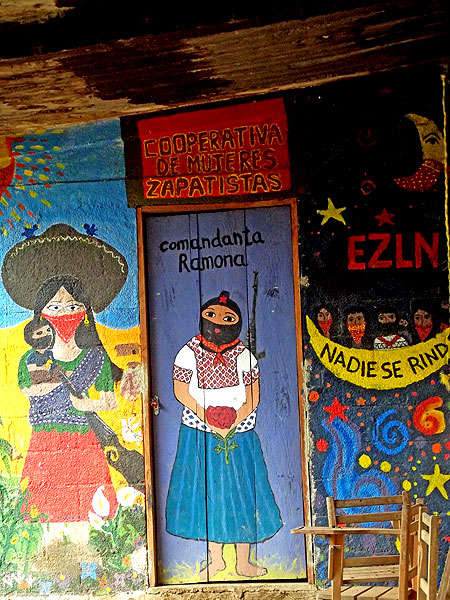

Beyond this, the denunciations released by all of the Good Government Council (JBGs) during these months have increased significantly, all of them addressing conflicts between support bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and members of other social organizations or political parties, whether over agrarian questions or those relating to territorial control. Perhaps the most serious case, one that the Roberto Barrios JBG has published several communiques on, has to do with the situation in the Comandante Abel New Community, official municipality of Sabanilla, in the northern zone of Chiapas. The Roberto Barrios JBG reported that on 6 September, a group of 55 masked PRI members carrying firearms and wearing military-type uniforms invaded a piece of land belonging to Zapatista support bases, resulting in the displacement two days later of 83 Zapatistas. The Roberto Barrios JBG has denounced the direct participation of the Secretary of Governance, Noé Castañón, in the planning and implementation of the escalation of violence in the region.

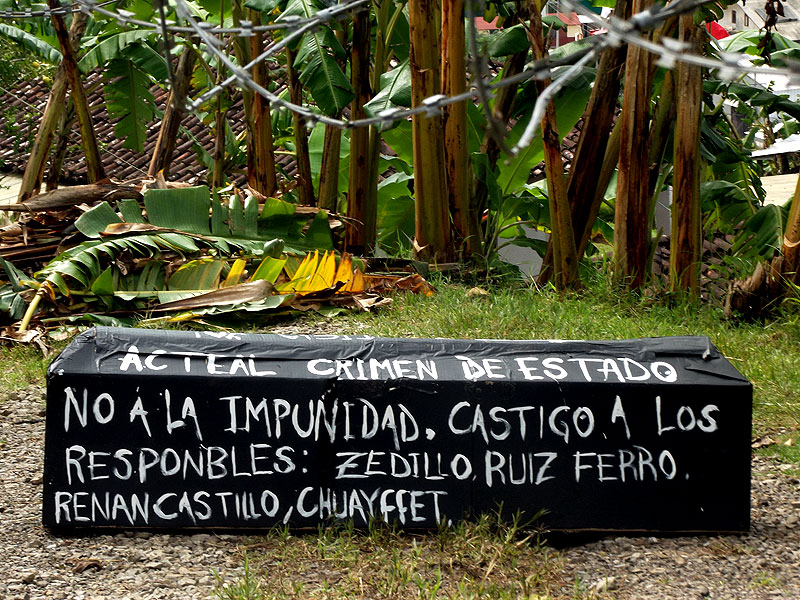

From the Highlands of Chiapas, the Las Abejas Civil Society in October denounced the reactivation of paramilitary groups in the Chenalhó municipality, in a manner similar to what is occurring in the northern zone of the state. Las Abejas affirmed that the mass release of prisoners previously imprisoned for the Acteal massacre which has been taking place from August 2009 to the present has “greatly favored the regrouping of these [paramilitary organizations], and now they are coordinating with those who were not judged; they carry firearms on the highways, in the mountains, and on pathways to milpas and coffee groves.” Las Abejas also reported that some time before, a Zapatista support base member had been shot in Yabteclum.

Impunity, a constant that fuels conflictivity

On 7 December, the U.S. State Department awarded former Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo diplomatic immunity, in light of the trial he faces for his presumed responsibility for the 1997 Acteal massacre. The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC) has affirmed that this decision represents an attempt to “protect not a person but rather a counterinsurgency strategy that was applied against indigenous communities in Chiapas by the Mexican Army, under the advice of its U.S. counterpart.”

Beyond this, in November the CDHFBC recalled that on 13 November 2006, a group of 40 persons from the Nueva Palestina community, accompanied by 300 police, invaded Viejo Velasco, located on the border of the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, leaving six people dead and two disappeared, besides provoking the forced displacement of 36 others. The CDHFBC indicated that through acts like this the “the six-year term of the government that will end its term in a few days was nothing more than one of makeup and illusion; the governor of the state, Juan José Sabines Guerrero, indebted the state in order to sell an image that scored points with some intergovernmental and governmental organizations of ‘support of human rights,’ when the grave rights violations that have occurred have been marked by the constant of impunity.”

Oaxaca: many bumps in the road two years into the governorship of Gabino Cué

Violence has worsened considerably in Guerrero, a key region in the transfer of drugs toward the center of the country, which is fought over by at least two criminal organizations: the Michoacán Family and United Warriors (Guerreros Unidos). The implementation of the program Secure Guerrero notwithstanding, the local population has demonstrated a strong rejection of the behavior of public security forces. In October, civil organizations, merchants, transport workers, and students marched in Acapulco to protest the “arbitrary actions and abuses” committed by members of the Federal Police (PF) since the launching of Secure Guerrero. At a subsequent rally, they listed a number of irregularities, including arbitrary arrests, unfounded accusations, and illegal detention of transport vehicles.

At the end of October, some 700 residents of Olinalá took the defense of their community into their own hands, installing barricades to impede invasion by organized crime. They expressed that they saw themselves as obligated to take these measures, in light of the lack of response on the part of authorities. Some days later, elements of the Marines arrived to carry out a security operation in this municipality. Members of the Regional Coordination of Communal Authorities (CRAC) affirmed that while the presence of soldiers could be positive in Olinalá, “when the federal forces leave the problems will continue.” They emphasized that the state and federal governments have not fulfilled their obligations of providing security to the municipalities located in the Mountain region of the state.

Finally, data from civil organizations revealed in September that up to August, at least 135 women have been murdered in 2012; for this reason, they consider a general declaration of alert for gender to be imperative. The Observatory of Violence in Guerrero “Hannah Arendt” noted furthermore that while the assaults against victims worsen, “sexual violence and torture prior to murder have been observed in a significant number of cases.” Gender violence is also on the rise: Guerrero has maintained third-worst place in the nation in these terms, after Mexico City and Chihuahua.

Two years after the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) handed down its sentences in the cases of Inés Fernández Ortega and Valentina Rosendo Cantú, indigenous women who were raped by soldiers in 2002, the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights emphasized that in these cases “although the investigations were transferred to civil courts a year ago, there is to date no indication that those responsible will be sentenced in the near term. This is due to the fact that the Secretary for National Defense has decided not to cooperate.” Days before, the Judicial Power of the Federation had sent a report to the IACHR informing that punctual observance had been made of the sentences of the Court in the cases of Rosendo Radilla (forced disappearance from 1974) and Valentina Rosendo.