SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (From mid-February to mid-May 2013)

27/05/2013

IN FOCUS : Impacts and affects of the wind-energy projects in the Tehuantepec Isthmus

04/09/2013The six-year term of Felipe Calderón from the National Action Party (PAN) was characterized by an explosion of violence in several regions of Mexico as a result of his frontal “war” strategy against organized crime, leaving a dramatic number of people killed, disappeared, or displaced. Enrique Peña Nieto, from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), ascended to the presidency promising a change to security strategies. Several organizations nonetheless have stressed that the only change between the two has been a discursive one, accompanied by a tendency on the part of the mass-media to discuss the question of the drug-war less (with the exception of the capture of particular ringleaders). The creation of a “national gendarmerie,” or militarized police, has been postponed on several occasions. In this sense, though the government has worked to contain insecurity, the devastation provoked by organized crime has not diminished.

In parallel terms, the government has advanced different parts of its political agenda. These aspects, set forth in the “Pact for Mexico” signed by the three most important political parties of the country, include reforms for labor, education, media, energy and finance (these last two still to come).

The opposition to the educational reforms manifested by the National Coordination of Educational Workers (CNTE) is still leading to mass-protests. Peña Nieto’s recent proposal for energy reform has provoked yet more controversy by those who consider it clearly to be framed in terms favorable to neoliberalism, given that it suggests that the State no longer retain a monopoly in the petroleum and electricity industries. The Movement for National Regeneration (MORENA), the political base-movement aligned with former center-left presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has already announced mobilizations for the month of September.

In social terms, the National Crusade against Hunger, which was to reach some 400 municipalities in a struggle against extreme poverty and food insecurity, reduced its scope and in fact never became a real solution in light of the precarious situation lived by an increasing number of Mexicans.

Human rights: avalanche of reports presenting Mexico as being in “humanitarian crisis”

In July, more than 30 civil organizations released a report on the human-rights situation in Mexico. This report anticipated the second Periodical Universal Exam (EPU) taken by the United Nations Council on Human Rights (CDH), which will occur in October. The report stresses the “exponential increase” in the numbers of human-rights violations, principally as derived from the context of violence which grips the country. It presents updated information, as well as giving recommendations in each of the 11 subjects it examines. The organizations emphasize that many of these recommendations were already released by the Mexican CDH itself in 2009; nonetheless, they have yet to be implemented by the State in an effective manner.

In June, several civil organizations pronounced themselves in observance of the International Day against Torture. The National Network “All Rights for All” has emphasized that “if the Mexican State has formally approved the proper international treaties on torture and subjected itself to periodical evaluations on human rights, the recommendations released by these mechanisms remain far from being implemented […]. In contrast, there is seen an increase in the practice of torture in our country, in addition to impunity.”

For its part, the UN High Commissioner’s Office for Human Rights presented a “report on the situation of human-rights defenders in Mexico,” which reveals that, from 2010 to 2012, it had documented 89 cases of attacks on activists, and that the authorities had prosecuted only three of the presumed individuals responsible for such attacks. The Office emphasizes that “the lack of punishment against perpetrators not only contributes to the repetition of the acts, but also aggravates the level of danger in which human-rights defenders carry out their work.”

Also in June, a year after the Law for the Protection of Human-Rights Defenders and Journalists was passed, more than 80 civil organizations indicated that “there exist grave obstacles and failures which impede the law’s adequate and effective functioning.” These groups identify three large problems: the lack of access to resources, the lack of trained personnel, and inadequate political and institutional support for the Mechanisms that are needed to be “adequately implemented at the federal, state, and municipal levels.”

This same month, Amnesty International (AI) presented a report on forced disappearances in Mexico, noting “the magnitude of what has happened and the negligence of the State” in doing justice for thousands of persons. According to this report, “between 2006 and 2012 there were more than 26,000 disappeared or lost persons registered in Mexico It is not clear how many of these continue presently to be disappeared. Some of these are the victims of forced disappearances in which public officials have been implicated.”

In May, AI declared that, despite the legislative advances which are supposed to favor Mexican women, they continue to live within a social environment in which they see their rights as violated. AI noted that the promises and discourses of good intentions on the part of the new federal administration are not translated into new, different realities; instead of being reduced, rights-violations continue to increase. According to AI, this year there were 14,000 rapes reported, but guilty sentences were found in only 21 of these cases.

Chiapas: Social conflict and changes in the state government

The most significant change in the state government of Chiapas took place in July when Manuel Velasco Coello, governor of the state, named Eduardo Ramírez Aguilar as the new Secretary General of Governance, replacing Noé Castañón in this charge, who had held the position during the majority of the previous government of Juan Sabines.

This change was attributed to the necessity for another type of response in light of the growing conflictivity and social mobilizations seen in the state. On August, 6, civil organizations published the report “Generalized violence in Venustiano Carranza”; based on information collected during a Civil Observation Mission, the report “seeks to clarify the violent acts which took place in Venustiano Carranza on 5 May.” The report notes that these acts found their basis in the “lack of interest on the part of the state government to profoundly resolve the demands of both groups. The government’s actions before, during, and after 5 May have generated polarization and a wave of violence in the municipality.” The report recalls “the result of these [factors] are the following: the murder of two persons […]; the displacement of 49 families, who to date live in a highly vulnerable situation without the government working to guarantee conditions for their return or relocation; damage to 42 homes, 22 vehicles, and 8 shops; the arbitrary detention of 19 campesinos […]; nine persons arbitrarily incarcerated; two tortured persons; and 167 arrest-orders which are still to be carried out.”

Another critical case is that of Colonia Puebla, Chenalhó municipality, where new aggressions that seem to have a religious basis coincided with the release of yet another group of those accused and incarcerated for the Acteal massacre of 1997. On 10 June, Catholics from Chenalhó denounced the looting of the land on which their chapel and construction materials are located, actions in which the ejidal authorities took part. On 18 June, they carried out a pilgrimage-march to Chenalhó so as to denounce the lack of attention from authorities. A month later, tensions increased once again when members of an anti-Catholic faction supported by ejidal authorities dismantled the construction site of the chapel. On 20 July, two persons, Mariano Méndez Méndez and Luciano Méndez Hernández, were detained and accused of having poisoned the community’s water supply. Both are from support bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). A third person, of Baptist denomination, was arrested for having manifested his opposition to such measures. They were released three days later, after no evidence was produced tying them to the charges of poisoning. But the problem at its root continues without resolution, this despite the signing of a civil pact on 8 August. The Las Abejas Civil Society has denounced that “the paramilitaries from Chenalhó are now reactivated, firing their weapons and causing displacements as they did previously in the year 1997.” Near the end of August, more than 90 persons (Catholics and two Baptist families) had fled Colonia Puebla.

Besides this, on 29 June, more than a thousand units of the state police invaded the Extraordinary Congress being held by Section 7 of the National Union of Educational Workers (SNTE) in Tuxtla Gutiérrez. As a part of this show of public force, more than 200 teachers were injured, some seriously, and 29 arrested, though they were released soon thereafter.

It should also be mentioned that women organized from the municipality of San Cristóbal de las Casas have declared a “Gender Violence Alert” amidst the refusal of the authorities to take adequate measures to detain violence against women in Chiapas. It has been calculated that there have been seen more than 55 femicides, and that dozens of women have disappeared since the beginning of the year.

© SIPAZ

Another source of mobilization has been related to prisoners. In June, upon completing 13 years’ imprisonment, events were once again organized to demand the release of Alberto Patishtán Gómez, an indigenous Tsotsil professor who is a member of the Voz del Amate, presently being held outside San Cristóbal de Las Casas. There was held a mass outside the prison, with hundreds of participants emphasizing the urgency of the matter. On 4 July, nine prisoners who adhere to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration of the Lacandona Jungle were released, an event also attended by governor Manuel Velasco Coello. However, neither Alberto Patishtán Gómez nor Alejandro Díaz Sántiz, a prisoner in solidarity with the Voz del Amate, were released on this occasion. In August, Amnesty International has added its voice to the call for the release of Patishtán.

During the time covered by this report, the EZLN published several communiques which were signed by either Subcomandante Marcos or Subcomandante Moisés. Some of them address the political context, while others discuss their new initiatives, such as the “little school” (Escuelita) and the creation of the “Trailblazing Lecture ‘Tata Juan Chávez Alonso'” which it organized jointly with the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) for 17 and 18 August (see article). More than 2000 students from different states of Mexico and other countries attended the “little school” which was held behind closed doors in the five Caracoles and the CIDECI-Unititerra of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. The students received a packet containing two CDs and several books dealing with the issues “autonomous government, participation of women in autonomous government, and autonomous resistance,” and they moreover were invited to stay with a “votán,” or an EZLN member who was especially designated to serve as comrade, teacher, and guide. During this time, it was denounced that “on 12 and 13 August during the night, military planes were engaged in overflights above the zones pertaining to the five Zapatista caracoles.”

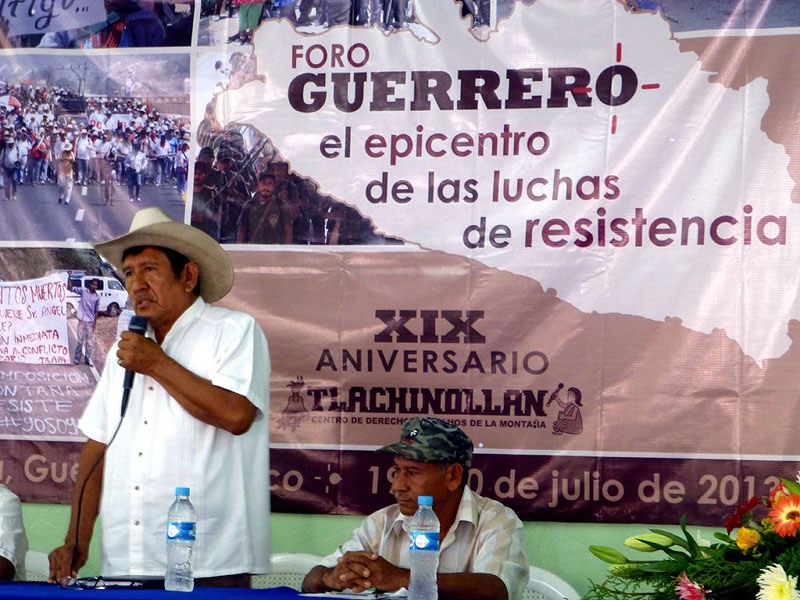

GUERRERO: Violence and ungovernability

© SIPAZ

In May, Humberto Salgado, Secretary General, resigned his position due to the crisis that the state government has been confronting amidst the spread of social conflicts, including protests undertaken by teachers’ movements over education reform and the proliferation of communal self-defense groups. Salgado was replaced by Florentino Cruz Ramírez, who resigned in turn at the beginning of July, supposedly because of his frustrations over being constrained in his political and economic operations. Jesús Martínez Garnelo has been named in his place . This second change re-enforced the perception of ungovernability which is experienced in the state, adding to the incessant waves of violence and executions. An example of this took place in June, when three activists—among them the PRD leader Arturo Hernández Cardona–were killed three days after a commando-group abducted them from Iguala, together with another five others who succeeded in escaping. A series of kidnappings has also been denounced which has targeted government workers. Beyond this, in the Sierra, drug-trafficking groups have, due to their violent disputes over production and transport pathways, provoked the displacement of at least 2000 people from three municipalities: San Miguel Totolapan, General Heliodoro Castillo, and Apaxtla de Castrejón.

Within this difficult context, impunity prevails and few spaces remain open for social actors who seek change. Civil organizations have denounced that the Federal Secretary of Governance claimed as complete the process of observing the sentences emitted against the Mexican State by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights (IACHR) in the cases of Inés Fernández and Valentina Rosendo, indigenous women who were raped by soldiers in 2002. In June, some 500 persons, members of civil and social organizations, marched in Coyuca de Benítez to commemorate the eighteenth anniversary of the Aguas Blancas massacre of June 1995, in which 17 campesinos were killed. Protestors denounced that eighteen years on, justice has not been realized, and they demand that the case be re-opened, such that those responsible be punished, especially in light of the continuing policies of repressing social leaders today.

Another question that has been raised by social processes in Guerrero has been to reject militarization. In August, the Collective against Torture and Impunity (CCTI) reported that Julián Blanco, one of the leaders of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP), was harassed for the sixth time by soldiers. In other news, Communal Police in El Paraíso, Ayutla de Los Libres municipality (pertaining to the CRAC, Regional Coordination of Communal Authorities), blockaded roads to reject the structural reforms advanced by the Pact for Mexico and to support the coastal peoples (like CECOP) in their struggles against military harassment. They affirmed that their principal demand of the state government is that it put an end to the harassment carried out against them by federal, state, and municipal police, as well as that exercised by the Army and Navy. For its part, the Regional Coordination for Security and Justice-Communal and Popular Police (CRSJ-PCP) demanded that the “Guerrero and Mexican governments immediately withdraw the Army from our communal lands. Here we do not need your services; here we watch out for and protect ourselves.”

OAXACA: relative political continuity despite increase in number of red alerts

On 7 July in Oaxaca, elections were held among the system of political parties for State Congress and municipalities. The “United for Development” alliance comprised of the PAN, PRD, and Labor Party (PT) won 14 out of 25 electoral districts for State Congress, thus maintaining its majority in the legislative branch. The alliance also won the majority of disputed mayorships, but it nonetheless was defeated for mayorship of the state capital. It should be mentioned that both before the elections as on the day of the elections, several violent incidents took place in relation to these elections.

Nonetheless, these electoral results, which in a sense entrenches the political parties who carried Gabino Cué to the gubernatorial palace, do not accurately reflect the various challenges that have recently been launched against the present administration. Civil organizations published the report “Human Rights in Oaxaca 2009-2013, Citizens’ Report: A Pending Debt.” The Report notes that, while in the period under examination there were seen legislative advances, these did not often translate into applied public policy. It notes the principal problems of the state: attacks on human-rights defenders and impunity for past such crimes, an official rights-defense ministry that does not award precautionary measures, having neither personnel nor budget; indigenous peoples who are greatly marginalized, lacking access to the justice system and facing the violation of their collective rights through the construction of megaprojects; criminalization of social protest; torture; arbitrary arrests; extrajudicial executions; and forced disappearances, among other human-rights violations.

In observance of the Forum “Defense of Human Rights in Oaxaca,” which was held in July, civil organizations have denounced that the number of attacks on rights-defenders and journalists in Oaxaca has increased to an alarming degree since 2012. These organizations noted that “between 2012 and 2013 there have been 35 attacks registered against rights-defenders, thus placing Oaxaca as the state with the greatest number of aggressions on human-rights defenders.” They mentioned as cases that had taken place in the recent past days the following: “armed and masked persons arriving in broad daylight to the home of Mariano López from the Popular Assembly of Juchitan; the disappearance on 15 July of the rights-defender Heron Sixto López, a Mixteco indigenous person and member of the Center for Orientation and Assessment of Indigenous Peoples from Santiago Juxtlahuca [whose body was found some days later]; and the violent death of the journalist Alberto López Bello, from the local daily newspaper El Imparcial.”

In May, the birth of the “Network of Communal Human-Rights Defenders of the Peoples of Oaxaca: Defending Territory, We Sow the Future” was announced. They stressed that “in Oaxaca it is the communal defenders who confront the greatest risks, given that they are the ones who most directly face the abuses of power exercised by the municipal authorities; they also are at the mercy of the established powers and regional actors who support projects that loot their territories and natural resources.” Harassment, aggressions, and murders have been reported among other crimes in the Tehuantepec Isthmus, where part of the populace has been organizing to oppose the construction of wind-energy parks in the region, as well as in San José del Progreso (against the mining operations carried out by the Cuzcatlán firm).

It should also be mentioned that a multiplicity of activities have emerged to protest the growing wave of violence against women, which has led to the disappearance of 58 women and girls so far this year, as well as against the irregularities exercised by the corresponding authorities.