ANALYSIS : Mexico – Between structural reform and “humanitarian crisis” over violence

04/09/2013

ARTICLE : The Trailblazing Lectures of Tata Juan Chávez Alonso – Never Again a Mexico Without Us

04/09/2013“We know that the problems of looting of land and natural resources which occur throughout Latin America and within Mexico correspond to a predatory and exclusive form of capitalism, which materializes through the imposition of megaprojects for mining or electricity production in indigenous territories, as in the case of the wind-energy looting of the Tehuantepec Isthmus.”

The Tehuantepec Isthmus and wind-energy

In recent years, there have been seen important advances in the development of renewable energy, also known as “green energy” or non-polluting energy sources, within which is included the development of wind energy.

Among the arguments used in favor of the development of this type of energy resources are those which make reference to the need to generate clean energy, in order to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases through replacing the use of the damaging fossil fuels. However, questions related to the impacts and effects that projects dedicated to the development of such types of energy have on local people and the environment itself are not often taken into consideration.

As is noted in the statement made by the International Seminar on Energy Megaprojects and Indigenous Territory, “The Isthmus at the Crossroads,” the opposition to wind-energy projects has to do not so much with a rejection of clean and renewable energy, but rather to the means by which such projects are implemented. This is done without regard to the desires of local peoples, the impacts and affects these can cause, and what the benefit and use is expected to be from this generated energy: “we are not opposed to the usage of technology to produce energy through renewable energy, but yes we do reject its employment merely for the profitability of companies and to the detriment of peoples and their bio-cultural inheritance.”

The region of the Tehuantepec Isthmus, understood as comprising the states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco, and Veracruz, is considered one of the most important sites for the potential generation of wind-energy. Its geographical uniqueness (a narrow stretch of land between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans that is practically a plain) makes possible the generation of between 5000 and 10000 MW of energy per year, which is enough to provide for 18 million people.1

These circumstances led the region of the Isthmus to be increasingly developed since the mid-1990s with an eye toward proposed wind-energy plans associated with the “Wind-Energy Project of the Wind Corridor of the Tehuantepec Isthmus,” which has been promoted by large national and transnational electricity companies which are supported by Mexican State agencies as well as the international financial institutions, such as the World Bank.

In the state of Oaxaca there are currently wind-energy parks operating.. There are presently 15 wind-energy parks in operation with 13 more in different stages of planning and development. These sites take up 60,000 hectares of collective property and generate 1263 MW (a mere 10% of the electricity-generation capacity estimated for this region).2 In the case of Chiapas today, there is only one wind-energy park, although it is believed that the number of such projects will increase over time in the state.

According to data from the Mexican Association for Wind Energy (AMNDEE), of the 28 parks that have been built or planned (2014), 3 of these belong to the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) and so are public, while 5 are the property of national firms, 3 pertaining to dual ownership (CFE and private), and 17 to foreign private corporations. The data indicates that close to two-thirds of the wind-energy parks are controlled by foreign interests. Furthermore, a large part of the technology that is needed to generate wind-energy is manufactured only by Spanish (Gamesa and Acciona), Danish (Vestas), and US firms (Clipper). This means that, taken together with the aforementioned, the expansion of wind-energy resources in Mexico implies a great deal of technological dependence and loss of State control over the generation of energy and the strategic sectors of the country’s economy.3

Some of the private firms that have invested in the wind-energy projects of the Isthmus include the following: EDF (France); ENEL (Italy); the MacQuaire Infrastructure Fund (Australia); PGGM (Netherlands); Mitsubishi (Japan); Iberdrola, Gamesa, Acciona, Renovalia, Fenosa Natural Gas, Preneal, EYRA-ACS (Spain); and Peñoles, Grupomar, Cemex, and Grupo Salinas (Mexico), among others.

Bettina Cruz, representative of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Tehuantepec Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory (APIITDTT), has indicated that the majority of the wind-energy projects, beyond being owned by private capital, are destined to provide energy to other private corporations, not to the public network and hence the citizenry.4 These projects, known as “self-generation,” are governed by the principle whereby private firms produce energy for themselves or to sell to other private firms, thus implying a double effect of privatization of the nation’s energy resources. As one example, only 22% of the electricity generated by the wind-energy parks of Oaxaca reaches the public network, while 78% is destined to private corporations such as Bimbo, Wal Mart, Soriana, Cemex, Cruz Azul, Grupo FEMSA (Coca Cola, Heineken, Oxxo), etc.5

Impacts of wind-energy projects in the Isthmus

© SIPAZ

Since the mid-1990s, the development of wind-energy projects in the region of the Tehuantepec Isthmus has been resulting in different sorts of impacts.

In a recent report carried out by different civil organizations from Oaxaca, the violations of the rights of indigenous peoples implied by the planning and execution of developmental megaprojects have increased over the past four years. Among the megaprojects in question, there are explicit references to wind-energy ones.6

Political impacts:

Legal challenges of these wind-energy projects have to do with the violation of local decision-making norms and the legal agreements to which Mexico is a signatory (the second article of the Political Constitution and the International Labor Organization’s Convention 169, principally), for example the right to prior free and informed consent owed to indigenous peoples regarding all realities that affect their lands and territories, as well as the right to choose and participate in development plans and models which accord with their traditional ways of life. As an example, according to Bettina Cruz, on 21 March it was shown in the European Parliament that in not one of the wind-energy projects of the Isthmus had there been consultations carried out with affected peoples, nor had any possibility been made so that local peoples could participate in the design of the development plans to which they would be subjected.

In some cases there has been denounced the sale and ceding of communal and ejidal lands (jointly owned lands) through force and without the consent of the general assemblies of communards and ejidatarios. Such negative developments have been tied to policies of cooptation advanced by firms, local authorities, and social leaders. As an example, communard assemblies from the San Dionisio and San Mateo del Mar municipalities have accused the ejidal president and the mayors of having accepted bribes made by firms to strengthen ties between the two forces, without any concern for the wishes of the community.

Beyond this, acts of criminalization, death threats, and attacks constitute other forms of the most significant political impacts. National and international organizations have been denouncing the numerous attacks suffered by rights-defenders, opponents to wind-energy projects, and landowners who demand compensation and better contract conditions.7

The rent contracts for land signed by firms and the commitments they have attained with respect to local populations of the zones in which the wind-energy plants are erected form yet another source of denunciation and conflictivity. For example, the Digna Ochoa Center for Human Rights from the coastal region of Chiapas warns of the lack of information and clarity of the contracts that have been agreed to. They often have been signed under the pressure of companies and include abusive implications for landowners in terms of the modification or cancellation of said contracts. Furthermore, the unjust compensation paid for the rent of such lands is stressed, given that such amounts go much lower than they should: a same-sized plot of land dedicated to the installation of a wind-plant will cost 9300 pesos per year ($670 US), as in the case of the La Venta III wind-energy park in 2012, while in Spain costs for such would oscillate between $5000 and $9000 annually.8.

Social and cultural impacts:

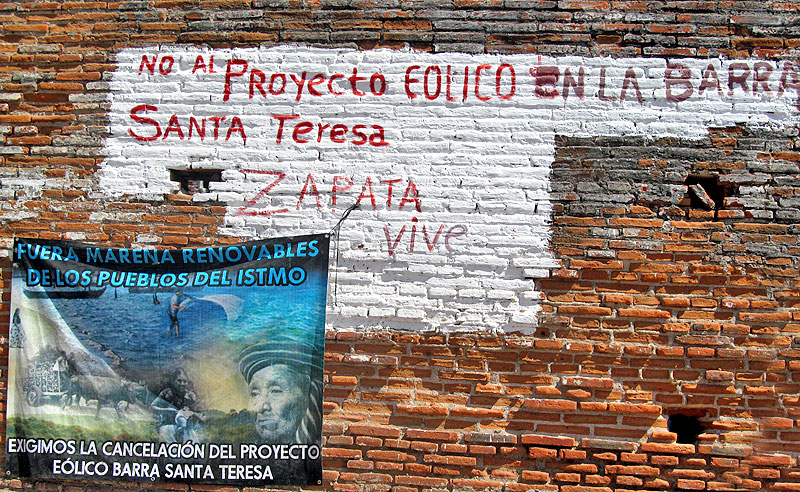

The divisions in communities and the degradation of the social fabric represent two of the principal social impacts confronted by the populations that are affected. Cases of cooptation of communal leaders, as already described, as well as offers of money to campesinos so that they do not present opposition to the interests of firms, and the sowing of rumors and distrust among the populace so as to provoke confrontations have all been indicated by different social organizations as abusive practices carried out by corporations such as Iberdrola, Fenosa Natural Gas, and Mareña Renovables. For example, the irregular organizing of a General Assembly of communards as promoted by Mareña Renovables on 29 December 2012 in San Dionisio del Mar had the objective to revoke a motion that had been placed by the community in order to impede the continuation of the company’s construction of the wind-energy park Barra de Santa Teresa. The outcome to this irregular session was a physical confrontation and a deepening of communal divisions among neighbors in favor and opposed to the project.

Among the cultural impacts, the above situation creates is the imposing of different culture values, being directed at the indigenous peoples of the region. It is a request to perceive nature and natural resources in commercial terms – a philosophy that does not necessarily agree with locals’ views of the world. Under the outsiders belief system, there is imposed a notion of decision-making processes based on majorities, which differs from the traditional emphasis on consensus-based decision-making processes.

The violation and destruction of spaces held by indigenous groups to be sacred or significant, such as the example of the Tileme Island in Barra de Santa Teresa, represents yet another type of cultural impact of these projects.

Economic impacts:

With the 1992 reform of the Law on Public Service of Electricity (LSPEE), the sector was denationalized, and so it was allowed that private capital could begin to generate electricity to sell to the CFE. With this change, by the end of 2010, private firms produced 33% of Mexico’s energy, while the percentage produced and sold publicly by the CFE increasingly declined. This situation has resulted in a marked increase in electricity prices, given the tendency of private firms to take an increasingly central role in the generation and sale of the electricity distributed by CFE to the citizenry, with the consequence that it becomes the private rather than public firms which have the capacity of dictating prices which are then paid in turn by consumers.9 This is a process which is more, within the commercialist logic that conflicts with concepts of public service, the destination of the major part of the energy which is generated in wind-energy parks is not for public but instead private uses. It follows then that many rural zones and popular neighborhoods go without infrastructure and electrical energy due to lack of profit potential as seen from the firms’ points of view.

This is a process which is more, within the commercialist logic that conflicts with concepts of public service, the destination of the major part of the energy which is generated in wind-energy parks is not for public but instead private uses. It follows then that many rural zones and popular neighborhoods go without infrastructure and electrical energy due to lack of profit potential as seen from the firms’ points of view.

Environmental impacts:

Among the environmental impacts resulting from the construction of wind-energy parks are those that have to do with the destruction of habitat and biodiversity. According to data from the World Bank, in only one year, the wind-energy park La Venta II provoked the death of some 9900 animals (principally birds and bats) after they collided with the blades of the 98 wind-energy turbines located in the park. It should be recalled that the Tehuantepec Isthmus is an important migratory corridor for birds; an estimated 12 million such birds travel through this region every year.10.

Wind-energy projects such as that of Barra de Santa Teresa or Bii Hioxho, located in the aquiferous zone of the Superior Laguna, also gravely threaten the flora and fauna of the mangrove ecosystem found in this area which, beyond providing life to a large number of aquatic and bird species, also represents the basis of the productive and nutritional system of fishing communities who live around the Laguna. According to criticisms from the APIITDTT, the impacts that could be seen in the construction area of the wind-energy parks would represent a serious threat to the food sovereignty of the populations of the region.

A final type of environmental impact is the pollution of soils, rivers, lakes, and aquifers due to the leaking of the oils used in the turbines, in addition to the accumulation of effluent originating in the construction yards, the erosion of soil and loss of vegetation, the electromagnetic noise pollution caused by the increased number of functioning wind-energy plants and, lastly, visual pollution of the landscape.11

Organization and resistance

Como consecuencia de las afectaciones ocasionadas por los proyectos eólicos en la región del Istmo, distintos colectivos de personas y comunidades se han venido organizando durante los últimos años en diferentes procesos organizativos y de resistencia. Entre estas experiencias cabe destacar (no son todas) la conformación en el año 2007 de la APIITDTT integrada por personas y pueblos de toda la región contrarios a la construcción de megaproyectos en sus tierras y territorios, la constitución de la Asamblea Popular del Pueblo Juchiteco (APPJ) el 24 de febrero del presente año para hacer frente a la construcción del parque Bii Hioxho en tierras comunales de Juchitán o la unión, el pasado mes de marzo, de las asambleas de distintas comunidades en la Asamblea de Pueblos Ikoots y Binniza’a.

Entre las demandas que exponen organizaciones y comunidades opositoras a los megaproyectos eólicos se encuentran el cese de la criminalización, las amenazas y las agresiones en contra de las personas defensoras de los derechos humanos y del territorio, y aquellas que hacen referencia al derecho de los pueblos indígenas a decidir un modelo de desarrollo propio y a ser consultados previamente a la realización de cualquier proyecto que afecte a su territorio y formas de vida. Relacionado con lo anterior, el derecho a la conservación, gestión y explotación de los bienes naturales que se encuentran en su territorio y el derecho a la soberanía alimentaria. El derecho a un desarrollo socioeconómico de la región y al suministro de servicios públicos regidos por una lógica social y no mercantilista, la contratación de personas de las comunidades en los proyectos que se desarrollen, contratos de arrendamiento de tierras legales y transparentes y el pago de rentas justas por las tierras utilizadas por las empresas serían otros de los reclamamos que pueblos y organizaciones realizan.

La forma en cómo las comunidades y organizaciones han venido defendiendo sus derechos al territorio ha englobado distintas actividades como: demandas civiles, mesas de diálogo, marchas, encuentros, foros, acciones directas, difusión informativa e incidencia a nivel nacional e internacional.

Actualmente el conflicto permanece abierto entre empresas, gobierno y comunidades del Istmo opositoras a la construcción de megaproyectos eólicos en sus tierras y territorios. No obstante, nuevos proyectos son anunciados como, por ejemplo, los del parque eólico Dos Arbolitos, de la multinacional española Iberdrola, o el parque Energía Sureste I-fase II, de la italiana ENEL.

Entre tanto, los pueblos del Istmo, además de resistir el embate de los proyectos eólicos, continúan planteando y construyendo un proyecto de vida y desarrollo propio basado en su sistema de valores y cultura. “Hemos defendido nuestro derecho a decirle NO al megaproyecto eólico de destrucción de la vida comunitaria y nuestro patrimonio biocultural. Emprendamos ahora la tarea de construir desde abajo y con la fuerza de las comunidades una propuesta propia: un plan alternativo de desarrollo para la región istmeña, que tenga como eje la reproducción y fortalecimiento de nuestros modos de vida, de nuestra cultura y nuestro territorio” (Pronunciamiento: Seminario Internacional Megaproyectos de energía y territorios indígenas “El Istmo en la encrucijada”. 26-28/07/13)

Notes:

- Castillo, Problemática en torno a la construcción de parques eólicos en el Istmo de Tehuantepec. México, Revista Desarrollo Local Sostenible Vol.4, nº 12., 2011, p.3. (^^^)

- Los Derechos Humanos en Oaxaca 2009-2012. Informe Ciudadano: Una Deuda Pendiente. México, 2013, p.9-10

Bracamontes, “Duerme 90% de potencial eólico“. Noticiasnet, 20/04/2013. (^^^) - Hugarte, Las multinacionales en el siglo XXI: Impactos múltiples. España, Ed. 2015 y más., 2012, p.103

AMNDEE (^^^) - Cruz, Ponencia. Seminario Internacional Megaproyectos de energía y territorios indígenas “El Istmo en la encrucijada”. Juchitán de Zaragoza, México, 26, 27 y 28 de julio de 2013. (^^^)

- Íbid, p.105 (^^^)

- Los Derechos Humanos en Oaxaca 2009-2012. Informe Ciudadano: Una Deuda Pendiente. México, 2013, p.9-10 (^^^)

- Código DH, Colectivo Oaxaqueño en Defensa de los Territorios, Red Nacional Todos los Derechos para tod@s, Red Nacional de Comunicación y Acción Urgente de Defensoras de Derechos Humanos en México, Proyecto de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales, A.C., Oficina Ecuménica por la Paz y la Justicia de Múnich, Amnistía Internacional, etc. (^^^)

- Íbid, p.107 (^^^)

- Hugarte.., p.97 (^^^)

- Ibíd., p.112 (^^^)

- Pronunciamiento del Foro Regional: Parque eólico del Istmo: Impactos ambiental, económico, social y cultural de los proyectos privados de energía eléctrica. Unión Hidalgo, México, 2005. (^^^)