2014

04/02/2015

IN FOCUS: “There is no news that is worth a life” – The courageous work of communicators in Mexico

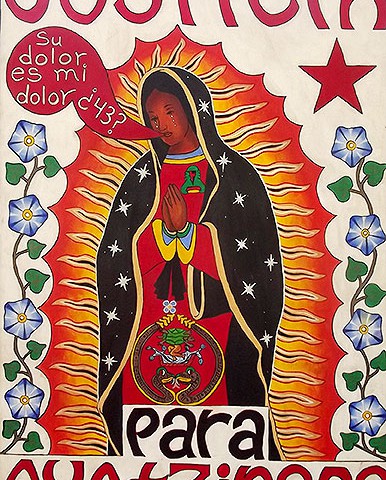

21/02/2015The forced disappearance of the 43 students from the Rural Normal School of Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, in September, and the scandals involving property sold by the Higa Group to President Enrique Peña Nieto’s (EPN) wife and the federal Housing Secretary under suspiciously advantageous terms, have negatively impacted the administration’s approval rating, which has reached the lowest levels since the beginning of the current presidential term. This all takes place furthermore within an adverse economic situation, one that is far removed from what EPN had promised during his campaign. The changes are due to the fall in oil prices and the depreciation of the peso against the dollar. According to the Bank of Mexico, the energy reform, which is considered the crown jewel of the structural reforms that were initiated at the beginning of this administration, is endangered by this context.

Ayotzinapa: an unconvincing investigative process

The actions of the federal government in regards to the case of the 43 students have provoked, step by step, the opposite effect from what the government desired, in the sense that it has failed to provide a credible explanation that would allow for “closure” in the case. During this process of investigation, increasingly more clandestine graves were found containing bodies that had not been expected, thus exposing a larger problem. Initially, the federal government presented the Ayotzinapa case as a “narcopolitical” problem that was limited to the Iguala region or at most the state of which it is a part, Guerrero.

Due to national and international pressure, the federal government found it necessary to follow the case more closely. The resignation in October of the PRD governor, Ángel Aguirre, did not succeed in silencing the mobilizations that expanded both within as well as outside of the country. In fact, the opposite took place. This limited the reading of the resignation as a mere attempt to prevent judicial action. By the end of November, the protests intensified in number and tactics, leading to the occupation of City Halls and damage to buildings and vehicles, with some of these actions likely involving the participation of agents provocateur.

In what has been interpreted as reflecting a desire to close the case indefinitely, the Federal Attorney General’s Office (PGR) reported on 7 November that the 43 students were presumably incinerated. The relatives of the students reject this account, and several independent investigators have pointed to various inconsistencies.

Faced with protests that would not stop, EPN in late November publicly announced ten actions having to do with public security and the administration of justice. These include a Law Against the Infiltration of Organized Crime within municipal authorities, which would allow the federal government to take direct control of security matters in municipalities in which there is evidence of collusion between officials and organized crime, and the obligatory creation of a single state police force that would substitute “more than 1,800 weak municipal police forces.”

In this regard, the parliamentary opposition groups have lamented that the Executive would transfer responsibility for the problem of security to the municipal level. Human rights and victims’ organizations recalled that this is not the first time EPN’s government has announced plans with no results to date. They lamented that there has not been any consultative process to develop the proposal. They warned as well that a large number of the measures do not imply immediate actions to move forward on the investigation of the more than 22,000 forced disappearances that have been denounced in recent years.

At the beginning of December, with the positive identification of the remains of Alexander Mora Venancio, the only student from the group of 43 who has been identified to date, the relatives of the disappeared announced that these remains had been planted to support the “official story.” During this period as well, it was reported that the Center for Investigation and National Security (CISEN) opened a file on the parents’ legal defenders, claiming they represented a “danger for governmental stability.” Civil organizations have lamented that the government would attempt to discredit them, and that public resources would be utilized to weaken the movement instead of combating the corruption of the “narcogovernments” and fighting against impunity.

In January, the same point of contention continued: the PGR reaffirmed its version that has been challenged not only by relatives of the disappeared, but also by Amnesty International. The Institute for Forensic Medicine of Innsbruck University (Austria) has reported that the “excessive heat has destroyed the DNA” of the remains that presumably belong to the disappeared students.

The relatives and the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights insist that the Army’s participation in the case be investigated, and that they be allowed to enter the barracks to search for evidence. Despite the initial opening provided by the Secretary of Governance, this demand has been rejected. On 12 January, relatives of the students had a confrontation with units from the military riot police and the state police as they tried to enter the military installations of Iguala.

In February, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) declared that the Ayotzinapa case “illustrates the serious challenges that the State confronts in terms of prevention, investigation, and punishment of forced disappearances and the search for the disappeared.” It recalled that the State has an obligation “to effectively investigate all state agents or organizations that could have been involved, as well as to exhaust all lines of investigation.” At the same time, the inconsistencies pointed out by the Argentine Team for Forensic Anthropology (EAAF) regarding the PGR’s investigation have strengthened the demand to open new lines of investigation. The PGR, for its part, has attempted to discredit the feedback provided by the EEAF. On 1 March, the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) will arrive in Mexico to begin the work of verifying the investigation in the case.

The temptation of repression

Several of the multitudinous protests in the country led to violence. For example, on 20 November in Mexico City, a group of youth launched rockets and attempted to break down the entrance to the National Palace. Riot police intervened against them and against the rest of the protestors who did not participate in such actions. This same day in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, after a group of people identified as infiltrators burned and looted stores, the police were deployed in force – long after the actions had occurred — leading to several arrests. In December, confrontations in Chilpancingo, Guerrero, left 22 people injured after a group of students who were preparing the “Light in the Darkness” Festival were attacked by police.

Amidst this grand social effervescence, the Chamber of Deputies in December approved a bill on “social mobility” that, according to the analysis of some NGOs and experts, could allow the authorities to stifle the exercise of the freedom of expression and the rights to protest and public assembly. Some legislators in opposition have qualified the law as an “anti-protest law.” The Front for the Freedom of Expression and Social Protest has indicated that it is alarming that the reform come now “within a context of enormous social discontent and public protests that have been met with disproportionate public force.”

A challenge that goes beyond Ayotzinapa

The Ayotzinapa case has created an unusual level of solidarity. However, it is not an isolated case: violence is part of daily bread in a society that has expressed itself in numerous mobilizations rejecting not only the disappearance of the students, but also the narcopolitical system that functions with near-total impunity.

The denunciations of corruption, particularly of the “White House” belonging to the president’s wife (which has been estimated as being worth 86 million pesos, equivalent to almost 6 million US dollars), revealed the “crony capitalism” (Proceso) that prevails in the country. Once again, the explanations that were provided by the Executive were unconvincing, but instead contributed to a further decline in the credibility and legitimacy of the authorities. This dynamic could have impacts on the elections coming up in June and July, when nine governors, 500 federal deputies, local congresses, and mayorships in 17 states of the Mexican Republic will be chosen.

Other actors have already called for abstention or turning in blank ballots. Within this debate, relatives of the disappeared of Ayotzinapa in February, together with public personalities such as Bishop Raúl Vera, Father Alejandro Solalinde, the poet Javier Sicilia, and members of civil and social organizations, churches, and unions, launched an initiative for a Popular Citizens’ Constituent Assembly for a new constitution to “create the democratic basis for the election of representatives of a new congress subject to the will of the citizenry, and forever buries all types of juridical and economic forms of organization that turns public administration into loot to be plundered. This constitution must put an end to impunity, racism, and patriarchy.”

Guerrero: Vulnerability of human rights defenders

Organizations close to the Ayotzinapa case, such as the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights and the Guerrero Network of Human Rights Organizations, have been subjected to campaigns of discrediting. Unfortunately, they are not the only vulnerable rights defenders in the state. In November, the team of the Workshop for Communal Development (TADECO) was threatened by means of a written note. In December, the body of the priest Gregorio López Gorostieta was found in the Tlapehuala municipality. During the past year, four priests and one lay person have been killed. Of the cases that have been reported, four took place in the Tierra Caliente region of Guerrero.

Vicente Suástegui Muñoz, brother of Antonio Suástegui Muñoz, the spokesperson of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP), who has been imprisoned since June, publicly denounced that in December, marines attempted to arrest him outside his home. In January, judicial authorities decided against the penal authorities, concluding that Antonio’s transfer to a maximum-security prison in Nayarit could not be justified. Therefore they ordered his return to a jail in Guerrero. Tlachinollan had filed an appeal based on “the argument that there exists a systematic pattern of utilization of maximum-security prisons to punish and silence social activists and communal defenders.”

In January, the interim governor of Guerrero, Rogelio Ortega Martínez, requested that the state attorney general suspend the charges against Nestora Salgado, who was arrested in August 2013 after individuals who had been arrested by the Communal Police that she led claimed to have been kidnapped. A federal judge dismissed these charges in 2014, but the state charges have remained. However, the petition was rejected by the attorney general following pressure applied by anti-kidnapping activists.

Chiapas paints itself green

© SIPAZ

Since the beginning of this school year, Governor Manuel Velasco Coello has distributed millions of backpacks and uniforms, all of them colored green, the color of the Party which brought him to power. Although the state is being painted green, environmental organizations such as Maderas del Pueblo del Sureste and the Na Bolom cultural association have challenged the government for its lack of a comprehensive and sustainable ecological approach, particularly amidst threats of reactivating mining operations in several parts of the state.

It is publicly known that Manuel Velasco seeks to run for president in 2018, seemingly following the media campaign formula used by Enrique Peña Nieto before his election. The media have reported that Velasco Coello has spent 500 million pesos of public monies on propaganda and public relations in less than two years in power. Furthermore, he has announced his marriage to a Televista actress—in another parallel to EPN and his wife. Since the release of Velasco Coello’s second report of his administration, the governor’s face is ubiquitous in the media and on public transit. Many other politicians are using this same strategy.

Despite the evident expenditures by Velasco and the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM), the Electoral Tribunal of the Judiciary of the Federation struck down the sanctions that had been applied to Velasco Coello for the presumed undue use of power to promote the governor’s image nationally. However, in mid-February, the same Tribunal decided that the publication of five banners on the website of a national newspaper which has contracts with the Chiapas state government to be improper.

In addition, on 21 December, the First Global Festival for Anti-Capitalist Resistance and Rebellion began in Mexico State. This event was headed by relatives of the disappeared students from Ayotzinapa, at the invitation of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) who gave them center stage. The Festival included the participation of more than 80 organizations comprising the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) that represents 35 indigenous ethnicities as well as adherents to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle from all of Mexico and 26 other countries. The EZLN members who participated in the event did so “with faces uncovered so that they cannot identify us. Or, better still, so that they identify us as just one more in the number.” The Festival closed in January in Chiapas, after having held “sharing” events in four different states. In the Oventic Caracol, Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés emphasized that “what is now most important is truth and justice for Ayotzinapa,” given that “the most painful and outrageous matter of all is that the 43 are not here with us.”

© SIPAZ

In addition to massive marches in solidarity with Ayotzinapa, in November, in observation of the International Day against Violence and Exploitation of Women, thousands of persons belonging to the Believing People of the San Cristóbal diocese held a simultaneous pilgrimage in 12 municipalities of Chiapas to express their rejection of the San Cristóbal-Palenque highway, their demand for justice for the disappeared students of Ayotzinapa, and their repudiation of violence against women, alcoholism, the Energy Reform, and corruption, among other themes.

Also, close to 250 women and men marched that same day in San Cristóbal, given that they view “with great concern the fact that big capital is at war with all the peoples of the world, because it wants to plunder us from our lands and territories to make investments in mining firms, airports, hotels, highways, ports, genetically modified seeds, monocultures, hydroelectric dams, and so on.”

In the case with greatest tensions, in December 2014, more than 300 ejidatarios from San Sebastián Bachajón, Chilón municipality, peacefully recovered the lands on which access to the Agua Azul waterfall is located. On 9 January, at least 900 state and federal police evicted the ejidatarios’ camp. Subsequently, the ejidatarios installed a regional headquarters for the ejido. They have continued to denounce that police presence continues, that the ejidal commissioner and his security aide are organizing paramilitary groups to “open fire at night with high-caliber weapons,” and that they have “information that they are preparing arrest orders to forcibly disappear the organization and remove us from our new San Sebastián headquarters.”

In terms of the omnipresent question of impunity, 17 years after the Acteal massacre in the Chenalhó municipality, the Las Abejas Civil Society denounced that “17 years, four presidents, and two political parties in power have passed . . ., and not one of these has had the dignity, humanity, or decency to apply justice and recognize the truth of the Acteal massacre.” Bishop Felipe Arizmendi stressed that “it is unconscionable that nearly all those imprisoned for this crime have been absolved, just because there were judicial deficiencies in their legal processing, not because they were innocent.” It should be noted that only 2 persons linked to the massacre remain incarcerated.

Oaxaca: Some progress, but much remains to be done in terms of human rights

On 21 January, Elías Cruz Merino, leader of the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle (MULT) and official of San Juan Copala, was arrested as one of the presumed murderers of the human rights defenders Bety Cariño y Jyri Jaakkola (Finnish citizen). Both were killed in April 2010 as they participated in a humanitarian caravan headed to San Juan Copala. In February, members of the National Association of Democratic Lawyers (ANAD) denounced the death threats received by two female witnesses in the case following this arrest. Amidst the lack of protection and effective responses on the part of the authorities, the ANAD reported that it had decided to protect them itself with its own resources in a safe house and request that Finland grant them asylum for humanitarian reasons. ANAD also condemned intimidation and harassment of the judge and prosecutor who are involved in the case.

In February, civil organizations reported that Bettina Cruz Velázquez, who has worked with organizing efforts opposed to the wind energy projects in the Tehuantepec Isthmus, was exonerated of the charges against her stemming from a denunciation made by the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). In 2012, she was arrested for having participated in a protest in front of a CFE installation. While celebrating the resolution of this case, Santiago Aguirre, subdirector of the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Center for Human Rights, emphasized that this is an emblematic case of harassment that many other defenders suffer from in Mexico. In fact, in Mexico, the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA) calculates that, in the period from the beginning of 2013 to April 2014, 82 attacks were recorded against environmentalists, 35 of which took place in Oaxaca. The majority of these events took place within the context of wind energy megaprojects in the Tehuantepec Isthmus. In Juchitán a very controversial consultation process is proceeding to decide the fate of a planned wind energy project.

In this same region, on 5 December, two people were injured during a confrontation in San Dionisio del Mar between followers of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and members of the Peoples’ Assembly (ADPSM) of this community. The ADPSM group had set up a blockade to prevent the entrance of personnel from the National Electoral Institute (INE) who sought to organize extraordinary elections there. The Peoples’ Assembly denounced that the head of the State Electoral Institute of Oaxaca is responsible for these violent acts, “insofar as it is anticipated that there will not be the proper conditions for municipal elections due to the fallout from our recent struggle against the Mareña Renewables wind energy firm, in addition to the post-electoral conflict that has torn the social fabric. The federal and Oaxaca state governments seek to install functionaries in the municipality, so as to open the door to the firms.”

Also in February, representatives of 25 communities from the municipalities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus met, where they pointed to several cases of intimidation and threats from PEMEX (state-owned oil company) workers who had been preparing the land for the construction of a natural gas pipeline that would connect Jalipan (Veracruz) to Salina Cruz (Oaxaca). Participants of the meeting warned that these changes would cut them off from their lands. They also demand restitution of the damages caused by more than 30 accidents in the past 20 years, actions for environmental remediation and development in the region, as well as information and consultation regarding the planned Trans-isthmian Corridor Project.

In terms of impunity, on 25 November 2014, the eight years since the beginning of the confrontation between civil society and the police in 2006 and 2007 were commemorated, which led to the death of 25 people, the arrest of about 500, the torture of 380, and the forced disappearance of five. The Commission for Relatives of the Disappeared, Murdered, and Political Prisoners in Oaxaca (COFADAPPO) called on the recently established Truth Commission to provide real results to the people of Oaxaca. That same day, in commemoration of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, the problem was made visible in the state. Consorcio Oaxaca has documented 344 cases of femicides and 122 forced disappearances of women that have not been sanctioned in the past four years of the present state administration.