SIPAZ Activities (January – March 2005)

31/03/2005

ANALYSIS: Mexico, Between Electoral Pre-campaigns and the “Other Campaign” of the Zapatistas

31/10/2005The Zapatista Red Alert: Uncertainties…

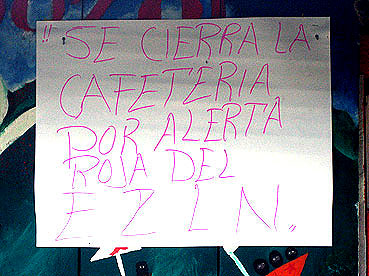

The Red Alert declared by the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) on June 20th again called the attention of Mexico and the rest of the world to Chiapas. In a communiqué, the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee-General Command (CCRI-CG) declared the closing of the civil autonomous structures, whose members were placed “under protection,” while making it clear that they would continue their work in a “transient” fashion. The state of alert throughout the entire rebel territory meant, in addition to the regrouping of the military command and the support bases, the quartering of the Zapatista insurgents who had been doing “social labor” in the communities, as well as the withdrawal of members of national and international civil society present in the autonomous communities at the time of the alert. The EZLN released all of the people, civil and political organizations, as well as solidarity committees from any responsibility for its future actions. At the same time, they declared the breakdown of relations between the Zapatista civil structure and the institutions of the Chiapas state government.

The Red Alert declared by the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) on June 20th again called the attention of Mexico and the rest of the world to Chiapas. In a communiqué, the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee-General Command (CCRI-CG) declared the closing of the civil autonomous structures, whose members were placed “under protection,” while making it clear that they would continue their work in a “transient” fashion. The state of alert throughout the entire rebel territory meant, in addition to the regrouping of the military command and the support bases, the quartering of the Zapatista insurgents who had been doing “social labor” in the communities, as well as the withdrawal of members of national and international civil society present in the autonomous communities at the time of the alert. The EZLN released all of the people, civil and political organizations, as well as solidarity committees from any responsibility for its future actions. At the same time, they declared the breakdown of relations between the Zapatista civil structure and the institutions of the Chiapas state government.

This was not the first time that the EZLN has declared a “Red Alert.” The first time was in 1995 during the federal government’s military offensive against the Zapatistas and the second in 1997 due to the massacre in Acteal. However, this current alert, announced as the ongoing process of building autonomy through action continues, sparked great uncertainty due to the reappearance of an unmistakably militaristic language, causing concern about a possible return to arms. It proved the existence – for those who attempt to minimize it – of the ongoing war in which both parties (the Mexican Army and the EZLN) remain armed and recalled the declaration of war of January 1994. Only with time, and with a reading of the subsequent EZLN communiqués, did people begin to speak of an “important political sign.” It became clear that the communiqués, beyond their militaristic nature, continued in the same vein of political and ideological struggle. Making use of their discursive abilities and their capacity for communication, the EZLN carried out a risky, but at the same time “provocative,” measure through which they announced a “new step” in the Zapatista movement.

…and the Birth of a New Initiative

In a second communiqué following the announcement of the Red Alert, the EZLN stated that since mid-June it had been building parallel an internal political and military restructuring parallel to its autonomous process, which has made them capable of responding to any kind of government attack. The third communiqué explained more clearly that the Red Alert had been a “preventative measure,” initiated to protect an internal consultation called by the CCRI-CG of the EZLN. It’s important to remember that in February of 1995, while the EZLN held an internal consultation, the federal government under Ernesto Zedillo launched a military offensive aimed at detaining the Zapatista Command. The EZLN reported that the current consultation was being held by the insurgents and the support bases in order to evaluate their years of struggle and resistance before deciding upon a “new step.” In the communiqué, they acknowledge that this new direction could cost them the “loss of the much or little that has been achieved.” They also indicated that in this new process “all Zapatistas are morally free to continue, or not continue with the EZLN in its next step.”

Later, in a letter addressed to National and International Civil Society, Subcomandante Marcos dispelled any doubts, declaring that the next step would not involve military action, again drawing closer to the pro-Zapatista civil society that has long accompanied the civil autonomous process and who were disconcerted by the closing of the Caracoles and the Good Government Councils (Juntas de Buen Gobierno – JBG), the public face of the Zapatista movement. The fifth communiqué informed the public that as a result of the consultations with the community assemblies, the EZLN had decided to embark on “a new political initiative of a national and international nature,” to be explained in the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.

It’s important to remember that the previous Declarations – except for the First one, which coincided with the declaration of war – called for the peaceful mobilization of civil society in order to bring about a holistic reform of the Mexican Republic. The Second Declaration (1994) announced the National Democratic Convention, the Third, the formation of the National Liberation Movement (MLN). In the Fourth, the creation of the Zapatista Front for National Liberation (FZLN) was announced and, in the Fifth, they launched the consultation for the Recognition of Indian Peoples and for an End to the War of Extermination. However, these various proposals did not always have the hoped-for results.

The Sixth Declaration sums up and evaluates the history and struggle of the Zapatistas during the last eleven years. In the extensive document, the Zapatistas underline that “we’ve arrived at a point which we cannot go beyond” and “a new step in the indigenous struggle is only possible if the indigenous join together with the workers of the city and the countryside.” They undertake an analysis of the current situation at a national and international level, in which they say that “a war of conquest in the whole world, a world war” is being waged. Therefore, at a national level, they propose the creation of a new “broad front”: “an agreement with people and organizations who are from the real left, because we think that it is in the political left where the possibility really exists to resist neo-liberal globalization, and to create a country where there is, for all, justice, democracy and freedom.” To make this possible, the EZLN will send a delegation to travel throughout the country for an indefinite time and to forge alliances with indigenous, worker, campesino, populist student, political and social groups, and, ultimately, unite movements against neo-liberal globalization. The objective of these meetings is to create “a national movement, but a movement that is clearly of the Left, and that is anti-capitalist.” In this way, the Zapatistas have again focused their strategy on a national level, embarking on an active strategy of alliance building. They’ve opted for reviving the general populace and “taking them out of” the logic of partisan electoral campaigns in order to create a movement for national structural change, including the writing of a new Constitution.

In addition, at an international level, the Zapatistas propose a new Intercontinental meeting in order to build networks with anti-globalization movements around the world. This meeting would follow the two “Intergalactic” meetings previously called by the Zapatistas: one in La Realidad (Chiapas) in 1996 and the other in Spain in 1997, both considered to be the origin of the global justice movements started in Seattle in 1999.

The Context of the Alert

The timing of the Red Alert was not casual. If the communiqué that announced this drastic measure of putting the Zapatista political-military structure in alert took us by surprise, it soon became clear that it was not a spur-of-the-moment act, but rather the fruit of a long process of reflection and analysis, not an end, but rather a beginning. It is important to analyze the alert within the context of the current national political scene and read it together with the communiqués released since last year. Just before the Alert, the EZLN released “The irresolvable power equation in Mexico.” In this communiqué, the EZLN affirms its opposition to the Mexican political parties, including strong criticisms of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), probable candidate for the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD), who has a good chance of winning the presidency. We recall that this year all national politics revolve around the presidential elections of 2006 and that in the last months, the largest social mobilizations were prevented at impeding AMLO’s elimination from the electoral race. Considered by many a populist alternative, compared to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil or Tabaré Vázquez in Uruguay, López Obrador is not considered by the Zapatistas to be a real alternative for the Mexican Left. In their proposal for the construction of an alternative project “to the Left and towards the bottom,” AMLO represents for the Zapatistas the “moderate Right,” which will continue in the same model of a nation dependent on international capital.

Various factors came together around the Red Alert, which increased the atmosphere of tension in the region. Weeks before, the Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Bank (BBVA-Bancomer) closed nine accounts held by Enlace Civil, A.C., the organization responsible for supporting projects in the Zapatista autonomous communities, based on an accusation of “illicit money laundering.” In addition, unusual regroupings of some military and police bases occurred in Chiapas, an event without precedent since 2001. These movements occurred without any explanation from the National Defense Department (SEDENA) and were not accompanied by any statements from other government officials. Army bases were closed in El Calvario (in the canyon of the river Perla), in X’oyep and in Los Chorros (both in the Highlands region), and in Bochil and Escopetazo (northern part of the Highlands region), as were two bases located outside of the “conflict zone.” Three weeks after the Red Alert, new military movements were noted in the municipality of Chenalhó; these movements do not indicate the withdrawal of the military from Chiapas.

Diverse Reactions to the Red Alert

Until now, there have been few responses from the Federal government to the Sixth Declaration. Xóchitl Gálvez, head of the National Commission for the Development of the Indian Peoples (CONADEPI) stated that “the Presidency of the Republic is awaiting communiqués from the Zapatista Army for National Liberation (EZLN) to see when and how they will carry out the announced actions.” The verbal manipulations of politicians and certain signs of war had preceded the EZLN’s proposed initiative.

On the same day as the announcement of the Red Alert, the SEDENA stated that during an operation executed on June 15, 16 and 17, they found and destroyed 44 marijuana plants in Zapatista territory. The media repeated this story, presenting the EZLN as a narco-guerilla force. Many politicians demanded explanations from the EZLN about their links with drug trafficking. Nevertheless, it soon surfaced that the municipalities in which the operation had taken place – Tapilula, Rayón, Pueblo Nuevo – are not only located outside of the so-called “conflict zone,” but also have no Zapatista presence. As a result, the Secretary of Governance had to deny the claim. It was feared that these accusations could have been used to justify a government counteroffensive on the eve of the Zapatistas’ new step.

In political power circles, the Zapatista proposal, even when the Sixth Declaration had not yet been published in its entirety, was interpreted as an abandonment of arms, the EZLN’s opting for the path of electoral politics, and even its transformation into a political party. President Vicente Fox gave “a most enthusiastic welcome to this communiqué and the EZLN’s opting for the political route and its departure from the armed path,” affirming that “he is at Mr. Marcos’s command to formulate a period of agreements and the integration of the Zapatistas into public life.” A spokesperson to the president assured that Mr. Fox was willing to cancel the long-standing arrest warrant out against Subcomandante Marcos, so that there are no obstacles to his full integration into political life. The government also insisted on its “willingness to dialogue” and on its “search for ways to come together.”

However, the Zapatistas have made clear that their new initiative does not mean returning to dialogue (that is, resuming the process of negotiation); it does not mean laying down arms; the declaration of war is not being withdrawn; and their transformation into a partisan political force has been entirely ruled out. Politicians read into the declaration what they wanted to hear, from the point of view of their own participation in the electoral process. This dissonance clearly demonstrated the distance between the two visions.

The Commission for Peace and Reconciliation (COCOPA) reminded the public that the 1995 Law for Dialogue, Reconciliation and a Just Peace in Chiapas continues to be valid. The Zapatistas, as long as they are respecting the ceasefire, are working within the framework of what is allowed by this law, and therefore do not need the arrest warrants to be lifted before they can launch their political initiative. The government commissioner for peace in Chiapas, Luis H. Alvarez, affirmed however, that “it is incompatible to choose a political path and remain armed.”

The state government, for its part, officially abstained from declaring a position on the Red Alert, “for lack of information” and because “it is a federal matter.” After two days, without providing further details, the state government announced that it too “had suspended all contact with the Caracoles and Good Government Councils.”

The Lifting of the Alert and Changes in the Civil Structure

Three weeks later, on July 11th, the CCRI-CG of the EZLN issued a new communiqué, lifting the state of Red Alert and announcing the reopening of the respective Caracoles and of all offices of the councils of the Autonomous Municipalities. At the same time, the Zapatistas extended an invitation to national and international society to resume contact with the Zapatista civil structure, whose work will gradually return to normal. In addition, as a result of the evaluation concluded during these weeks, the Zapatistas announced a reorganization within the Caracoles. In order to limit the involvement of the military wing of the EZLN in civilian life, a self-criticism made on various occasions, the Vigilance Commissions (Comisiones de Vigilancia) will be comprised only of the civilian Zapatista support bases. These commissions will serve as a bridge between the JBG and visitors. They will also keep the communities and Autonomous Municipalities informed so that they can be involved in consultations and keep an eye on the autonomous process “from the ground up.” Also, the creation of a new cell within the offices of the JBG was announced: the Information Commissions, in which they will attend to people who want to know more about the history and struggle of the Zapatistas.

Three weeks later, on July 11th, the CCRI-CG of the EZLN issued a new communiqué, lifting the state of Red Alert and announcing the reopening of the respective Caracoles and of all offices of the councils of the Autonomous Municipalities. At the same time, the Zapatistas extended an invitation to national and international society to resume contact with the Zapatista civil structure, whose work will gradually return to normal. In addition, as a result of the evaluation concluded during these weeks, the Zapatistas announced a reorganization within the Caracoles. In order to limit the involvement of the military wing of the EZLN in civilian life, a self-criticism made on various occasions, the Vigilance Commissions (Comisiones de Vigilancia) will be comprised only of the civilian Zapatista support bases. These commissions will serve as a bridge between the JBG and visitors. They will also keep the communities and Autonomous Municipalities informed so that they can be involved in consultations and keep an eye on the autonomous process “from the ground up.” Also, the creation of a new cell within the offices of the JBG was announced: the Information Commissions, in which they will attend to people who want to know more about the history and struggle of the Zapatistas.

Challenges of the New Initiative

The “new step in the Zapatista struggle” generates multiple challenges, not just for the Zapatista movement, but also for all of society. As they themselves have affirmed, it is a risky initiative, in its essence as well as because of the political situation in the country. This initiative has proven a variety of things. It confirms the Zapatista’s ability to launch a proposal driven by its own political vision, which addresses the particular political moment experienced by the country at large.

The release of this initiative also demonstrates that in order for the Zapatistas to be coherent in their struggle against neo-liberal globalization, it has become necessary for them to form closer ties with those international and Mexican movements that have experience in active resistance. This change in course coincides with criticisms that have been made of the Zapatistas of late: that they would continue on their path towards autonomy without undertaking concrete proposals “beyond Chiapas.”

Many of the movements and national social organizations who are in sympathy with the EZLN and also have ties to the national PRD or the network in support of Lopez Obrador, both of which belong to the institutional left, become obligated to define themselves in light of the Zapatista proposal. This could create some discomfort for those who have maintained their support for both and will determine the resonance of the Zapatista proposal in the different ‘lefts‘ they’ve identified.

Also it remains to be seen how this space will be articulated, a space which, due to its broad scope, implies not only certain challenges, but also the danger of repeating frustrated experiences such as the unsuccessful formation of a Constituent Assembly (proposed in 1994). To date, some organizations have expressed their support of the new Zapatista initiative, such as the Mexican Electrician’s Union (SME) and the Indigenous National Congress which, along with the Zapatistas, declared themselves “in red alert.” The response of other sectors of civil society remains to be seen; they will surely wait for the Zapatistas to further define their actions before making concrete statements. Another challenge for the Zapatistas will include drawing in organizations that were previously out of their sphere, but who now, faced with the country’s current situation, see in the EZLN proposal a political outlet for the nation. With this goal in mind, on June 13 the Zapatistas announced the formation of two commissions: the “intergalactic” one, which will develop the proposal on an international level, and a national commission, which during the month of August, will begin holding meetings with all of the organizations and people who are in agreement with the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.

It is relevant to point out that the ‘turning‘ of the Zapatistas towards national and international politics does not mean a de facto regression in the autonomous process. The autonomous structure headed by the Caracoles and the multiple education, production and health projects embodied in these regional centers represent advances in a variety of areas. Based in the process of internal evaluation, the Zapatistas have undertaken some changes intended to improve the function of the Caracoles. Without anticipating the progress of the new Zapatista proposal at national and international levels, we can nevertheless predict that two parallel processes will be sustained: the continuation of the building of alternatives from the ground up, which respond to local needs, and the formation of an intense political process aimed outward. These two processes will surely nourish each other.

In a “non-electoral” way, while making the most of the current political schedule, in which attention will be primarily focused on the upcoming elections, the Zapatistas want to demonstrate the relevance of making “another politics possible.” Therefore, they’ve opted to continue exerting pressure on the powers that be from outside the political system and to return to motivating and uniting the general populace in mobilizing for change. Given the impossibility that the “neo-liberal war” will ever be confronted from within the system, the Zapatistas have closed ranks in order to do so from the outside, with the people.