LATEST: International concern continues over the context of violence and human rights violations in Mexico

21/03/2016

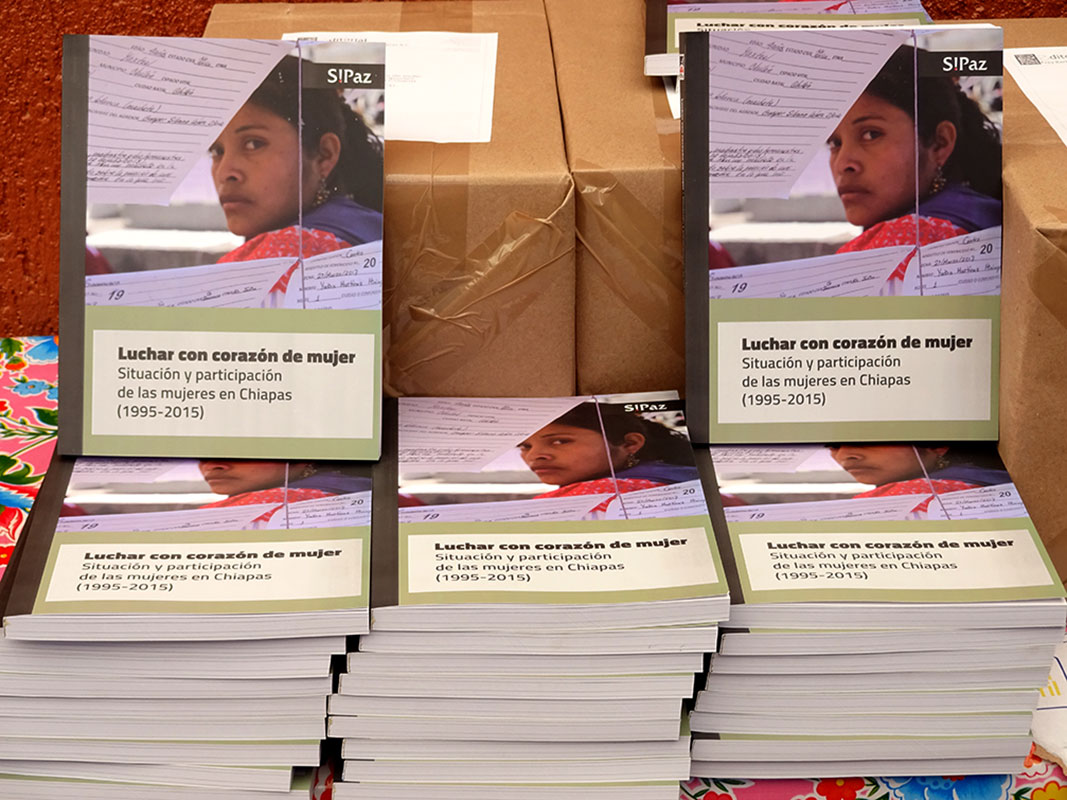

FOCUS: “Fighting With the Heart of a Woman ” – The situation and participation of women in Chiapas (1995-2015)”

21/03/2016At the end of November of 2015, the team and Board of Directors of the International Service for Peace (SIPAZ), together with more than 30 participants from different parts of Mexico and overseas, celebrated our 20th anniversary of presence in the south of Mexico. Although the permanence of SIPAZ for 20 years, despite the challenges that had to be faced can be seen as an achievement, it is still alarming that an international presence for peace is still necessary after this length of time. Even though, from this perspective there isn’t much to celebrate, with two decades of existence of SIPAZ, we thought that we have great capital to share about what we have learned along the path. As Ana Maria Garcia of Services for an Alternative Education (Servicios para una Educación Alternativa – EDUCA), Oaxaca, who gave a presentation at the event, “we are not celebrating that [fact that] the reality is the same but that we continue struggling with hope and dignity.”

Given this, we organized a meeting to exchange ideas about the changes in the political and social context of Mexico of the last 20 years, the situation and participation of women in Chiapas (see Focus of the Report), as well as responses and lessons learned from the civil society given the challenges. For two days we met with people from different social, civil, and campesino organizations, from the academic world and from different collectives. The event took place in an atmosphere of hope with a very positive general attitude, but fully aware of the numerous difficulties and challenges we have ahead.

The Firt Steps of SIPAZ

“We arrived twenty years ago in the middle of an openly declared conflict situation, in moments in which [bishop] Samual Ruiz calls on the community of solidarity to be present and look for solutions“, the current president of SIPAZ, Gustavo Cabrera, Costa Rica, recalled. In its first years, SIPAZ responded to a more “classical’ strategy of Civil Intervention for Peace. This strategy mainly combined international presence with the diffusion of information outside the conflict zone. With time, SIPAZ decided to open new areas of work to be able to contribute to the transformation of the context of structutal violence through the axis of Education for Peace, Inter-religious dialogue, and Networking.

Later, the activites of SIPAZ widened geographically: from 2006, the team began to be present in the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero, takiong into account the similarities of these entities with Chiapas as regards poverty and marginalization of the most vulnerable sectors of society. As Martha Ramirez Galeana, a young member of the Montaña Tlachinollan Center for Human Rights noted: “in those years, the 90s, democracy was turned around, and in thisevironment 500 years of resistance occurs, and the peoples begin to arise, it seemed that in Oaxaca, guerrero and Chiapas our struggles were the same.”

The darkness of the current context

Martha Ramirez referred a dawning of the peoples of different regions of southern Mexico due to the strong repression, such as the massacres of Aguas Blancas and El Charco in Guerrero, seeking responses to the system of oppression being lived. The people began to realize that “the state [wanted] to divide and break the consolidated struggles of the people.” The change that Martha sees today is the multiplication of agents in the system of supression. “Now, not only the ‘cacique’ State [wants to break and divide] now it is what we call the triangle of power: the state, businesses and organized crime.” Moreover, according to Ana Maria Garcia, member of EDUCA in Oaxaca, there is a subsantial tendency to identify ‘cultural pillage’ in the current context, which strongly weakens the peoples. ‘This strategy erodes the strength four peoples. Pillaging territories […], for example, but also the pillage of our dreams and hopes.”

Philip MacManus, who was the first president of SIPAZ participated by sending a video message which was shared in the event, spoke of the economic interests that threaten the welfare and unity of the peoples. “Division is a great threat that responds to various causes: it must be understood that there are distant interests to provoke divisions. Therefore a challenge is how to confront this phenomenon without falling into a perspective that sees it as a division between good and bad.” Another interpretation of the darkness of the social and political context that Mexico is living through was created by a group of children, some belomging to the displaced families of the community of Banavil, Tenejapa municipality, Chiapas, who were present at the event, accompanied by their fathers and mothers. They painted a 2×3 square meter mural about Mexico today. What began as a landscape with plants, flowers, hills, animanls and people, ended in a great balck stain. The children themselves named the work “The Disaster.”

Another world is possible: A global challenge

In the event, it was also argued that the context in which we find ourselves should be analyzed from a transnational persspective. In this regard, Gustavo Cabrera considered that “many of the times that local actors respond to a conflict situation, they lose this perspective, that it is not a local issue, but that it has a supranational and international root.” similarly, Richard Stahler-Sholk, member of the Baord of Direction of SIAPZ,, began the introduction of the panel on the Mexican context with reference to the context of globalization in which we find today’s reality. ‘The context of this table is a global context. It is a struggle to think about the possible golbalization as well as the the one we live, with this motto of the alter-globalization that is ‘Another world is possible. We must have faith in this other world and be aware we are building this other possible world’, he said. Dolores Gonzalez of of Services and Assessment for Peace, SERAPAZ, said that in this global context she sees: “three tendencies: ecological catastrophe, economic crisis, and permanent war.” She clarified that, at the same time, “it is important that facing darkness, we see the light. Atenco, La Parota, Paso de la Reyna, the Yaquis, San Javier, the Seris, the peoples on the Isthmus confronting wind farms, autonomous communities in Chiapas, and many other expressions of protest.” In this sense, Pedro Ameglio of the Service for Peace and Justice of the Service for Peace and Justice, Morelos, Mexico, underlined that “one comes to Chiapas to learn always and to learn, on a personal level, the closest definition of non-violence: ‘how to disobey inhumane orders, which for me is the definition of non-violence.”

The Lights of Hope

Another of the experiences of non-violent resistance presented was that of Tita Radilla, daughter of Rosendo Radilla, the social leader from Guerrero in the 70s, who was forcefully disappeared at a military checkpoint in that state in 1974. His daughter has carried on the search process for her father for 41 years, which has not given any result to date. Nevertheless, she emphasized that her efforts and those of her family have brought about changes in the Mexican judicial syatem, improving the chances that other cases of other people do not remain in impunity. Specifically, Tita Radilla referred to the sentence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) in 2010, in which the IACHR blamed the Mexican State for the forced disappearance of Rosendo Radilla and recommended that crimes committed by the military that involve civilians be tried by civil rather than military courts. This led to a reform of the Code of Military Justice, approved by the Senate of the Republic of Mexico in April, 2014.

Eloy Cruz, member of the Council of Peoples United in Defense of Rio Verde (Consejo de Pueblos Unidos en Defensa del Río Verde – COPUDEVER) of the coast of Oaxaca, in his presentation on the panel about lessons learned, said that “fear of government must be lost’. He told how the Federal Electricity Commission (Comisión Federal de Electricidad – CFE) came to the communities that would be affected by the Paso de la Reina hydroelectric dam saying that “you are the last [to sign].” The comuneros realized that this was the government strategy to convince them and that “it was necessary to convene the 47 communities to clarify that we hadn’t accepted anything. It turned out that it was the strategy of the CFE. But we look after the ejido as one would look after his home.” This way of resisting entering the plans of others, governments and companies, is what Pietro Ameglio calls non-cooperation. As he explained, “This is the scheme of non-cooperatrin that is the key to Zapatismo and Ghandism, power is in us, not in them, we don’t need to as them to do what they are not going to do, but we have to be conscientious and act..” Realizing the importance of being informed, the members of COPUDEVER have had local, national, and even international forums. They have also involved the general public distributing information leaflets in the streets and also through public festivals.

Another way of building the other possible world, as the president of the civil society Las Abejas de Acteal, Jose Alfredo Jimenez, commented in 2015, is through denouncing. “For us, to struggle is to denounce, not to remain silent in the face of injustice. To be pacifists implies working, building peace, this doesn’t come from nothing, it is built.” The organization of Las Abejas was born in 1992 and since then has opted for struggle and the method of active non-violence. Jose Alfredo explained that another strategy of the government to create conflicts is to call problems in communities “inter-community conflicts.” He recalled that ‘that was how they mentioned it officially after the massacre of Acteal.” Instead of falling into vengeance and taking arms to harm brothers and sisters who took part in the massacre, Las Abejas de Acteal decided to use their voice: they have denounced the situation of injustice and impunity for 18 years since December, 1997.

The video-documentary titled That the Heart not be broken (Que el corazón no esté partido), that SIPAZ produced in 2015 as part of the project of systematization of the learnings of the last 20 years, Jose Alfredo Jimenez explained that in the Tsotsil language of the Highlands of Chiapas the term ‘peace’ is translated as “jun o´ontonal”, which can be understood as “a heart” or that ‘the heart not be broken.” It refers to the fact that the people remain united in difficult moments and that problems and conflicts not generate divisions. As Martha Ramirez also commented, being Me’phaa indigenous from Montaña de Guerrero: ‘The grandparents say that what is amde of heart never dies.” With this message from the full heart guided by the lights on the path which closed the event to celebrate 20 years of presence of SIPAZ in the south of Mexico. Celebrating that we continue struggling with hope and dignity…