SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (Start of April, 2016, to mid-May, 2017)

27/06/2017

FOCUS: Gender violence alerts: understanding the problem to be able to deal with it

26/09/2017From May 26th to 28th, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI in its Spanish acronym) was held to form the Indigenous Council of Government (CIG in its Spanish acronym) and to appoint its spokesperson who will be independent candidate for the presidency in 2018. 858 representatives of 58 indigenous peoples participated, guests, observers, as well as the general command of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN in its Spanish acronym).

Mural of “CompArte for Humanity – Against Capital and Its Walls, All the Arts” convened by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, July 2017 © SIPAZ

Two councilors, one woman and one man, were appointed for each indigenous region participating in the CNI, except for the people residing in the metropolitan areas of Mexico City and Guadalajara, in which cases a single councilor was appointed per town. Maria de Jesus Patricio Martinez (Marichuy), 57 years old, a Nahua native from Tuxpan, Jalisco and a traditional doctor, was appointed spokeswoman for the CIG. She reaffirmed that the process they are undertaking as indigenous peoples is for life and not for power, and that it is not only for indigenous peoples, but for all sectors of society.

Since that date, the CNI has repudiated “the escalation of repression against colleagues in our villages where they have been nominating council members for the composition of the Indigenous Council of Government.” In June, it reported threats, attacks, arrests and a murder in four communities in Chiapas, one in Queretaro, one in Morelos, one in the State of Mexico, one in Michoacan, one in Campeche, as well as the situation of Mayan indigenous people of Guatemala who are displaced in Campeche.

On an international level, in June, during the 47th regular session of the General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS) in Cancun, Quintana Roo, Mexico, the Plan of Action on the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was approved. It had been ratified in June of last year. Animal Politico website said that, given what was discussed, indigenous peoples pleaded with the OAS to “respect the self-determination and autonomy of our peoples over our territories and natural assets”, to “implement prior, free and informed consent on any issue that affects them” and that consultations are not carried out when there are already “agreements, permits, licenses and previous contracts because these consultations are part of a simulation.”

This request finds a strong echo in the demands of the Indigenous Peoples of Mexico. For example, in June, the Mexican Network of Workers Affected by Mining (REMA in its Spanish acronym) questioned the limitations of the Report presented by the United Nations Working Group on Human Rights and Corporations after its visit to Mexico in September 2016: “Our complaints and indications expressed the disrespect of our right to consent or not to their projects that seek the dispossession of our natural assets, but this does not mean that we were requesting the consultation as a solution; on the contrary, we emphasized that we have assumed what is said in our constitution, laws and international conventions and declarations: the full exercise of our right to self-determination, (…) we are the ones who are conducting our consultations, our assemblies, specifically to avoid that now, with the modes and the auspices of the guiding principles, these governments and companies violating rights, impose mechanisms and procedures as they wish”.

In fact, at the end of July, the civil organizations that made up the Civil Society Focus Group on Business and Human Rights disengaged themselves from the two-year process to create a National Business and Human Rights Program (PNEDH in its Spanish acronym), considering that the proposal presented by the Mexican government does not meet international standards.

Negotiation of Free Trade Agreements with elections in 2018: of greater concern for the players in power

“CompArte por la Humanity – Against Capital and its Walls, All the Arts” convened by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, July 2017 © SIPAZ

In June, 129 Mexican civil society organizations expressed their concern that while Mexico “is plunged into an ever deeper human rights crisis recognized by all international human rights bodies”, negotiations for “modernization” of the Global Agreement between Mexico and the European Union are speeding up. They pointed out that a new Global Agreement “with a purely commercial focus” can “deepen inequality, violence against defenders, journalists and the population in general; that is, it would deepen the human rights crisis in the country.”

In mid-August, the United States, Mexico and Canada also began renegotiating the trade agreement that the three countries have maintained for 23 years. It will not be an easy negotiation, since, from his campaign, the US president, Donald Trump, has not stopped attacking Mexico and has claimed that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has damaged the American economy. The free trade area, opened in 1994, covers 450 million people and represented $ 1.2 trillion in commercial transactions in 2016. Security and migration issues are two sensitive issues that will have to be addressed.

Defenders and journalists still targeted

In June, The New York Times reported that Mexican journalists and activists were spied on with a software called Pegasus, which infiltrates phones and other devices to monitor details of a person’s daily life. The company stated that they sell that application “exclusively to governments on the condition that it is used only to combat terrorists or criminal groups and drug cartels” and that only a federal judge can give permission to monitor private communications. According to several ex-officials of the Mexican intelligence services “it is very unlikely that the government has received such approval.” There is no definitive evidence to prove that the Mexican government was responsible because “Pegasus software leaves no trace of the hacker who used it. (…) But cyberexperts can verify when the software has been used on the phone of a target, which leaves little doubt that the Mexican government or some internal corrupt group are involved. “

The federal government ruled that “there is no evidence” that government agencies are involved, and asked that those spied on denounce the alleged intrusion. Several did, although they doubt that it will have results since the government would have to be judge and jury in this case. In protest at the case # GovernmentEspía, journalists and defenders symbolically surrendered to the Attorney General’s Office (PGR in its Spanish acronym).

CHIAPAS: Development – a clash of two visions

Pilgrimage of the Indigenous Movement of the Zoque Believing People in Defense of Life and the Earth in Tuxtla Gutierrez, June 2017 © SIPAZ

In August, President Enrique Peña Nieto arrived in Chiapa de Corzo together with the governor of Chiapas, Manuel Velasco Coello, to commemorate “International Day of Indigenous Peoples”. According to Aristegui News: “From a day before their arrival, residents of Chiapa de Corzo expressed their rejection of the President’s visit and declared him a persona non grata … because he has reformed the laws against the Mexican people, he has handed over its natural resources, has given away the oil, energy, and will go on to hand over our people.” Although the state and federal governments had vowed not to retaliate in exchange for seven federal police officers being held, the alleged perpetrators were arrested and charged with rioting and disturbing the peace. During the speeches, both EPN and Manuel Velasco gave importance to the application of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), a project that aims to make specific regions a priority for investment, stating “that economic policy that now only contemplates the area of Soconusco Chiapas, must be replicated in the indigenous region.”

The SEZs are not the only supposed development projects questioned by the peoples. In June, the Indigenous Movement of the Zoque Believing People in Defense of Life and the Earth organized a pilgrimage in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, where approximately six thousand people participated. This movement resulted from the bidding process for the concession of “a total of 84,500 hectares of land in nine municipalities in the north of Chiapas [which] would be used for the extraction of natural gas through the dispossession and environmental contamination of Zoque territory.” Since March 2017, this movement has reported irregularities in the bidding process since all affected communities have not been consulted, nor have there been translators in Zoque and neither has the Environmental Impact Statement been issued as required by law.

Pilgrimage of the Indigenous Movement of the Zoque Believing People in Defense of Life and the Earth in Tuxtla Gutierrez, June 2017 © SIPAZ

Similarly, in August, the June 20th Popular Front in Defense of Soconusco (FPDS in its Spanish acronym) warned of growing social tension in Acacoyagua, where it has been peacefully struggling for more than two years for the cancellation of 21 mining concessions in this municipality and that of Escuintla. It denounced two assaults: “On July 31st, a group of 50 people … came to our camp … to intimidate us and to ask us to let the trucks from El Puntal mine go to the “Casas Viejas” mine.” When, on August 4th, they handed in a letter to report this aggression, “about 100 people … began to provoke us as well as the organizations that accompany us and verbally delegitimize our work in defense of life (… ). The intervention of the municipal police was needed to stop the aggression.”

Environmental problems can affect both the countryside and cities. In June, La Jornada newspaper published an article on the “extraction, for more than seven decades, of 52 sandbanks and gravel of hills east of San Cristobal de las Casas,” which “has caused geological formations to be exposed and produce severe erosion processes” as well as “pollution problems in areas near the generally inhabited sandbanks.”

Equally unresolved territorial conflicts of a different kind

In June, both Tila ejido and the organization United Peoples for the Defense of Electric Energy (PUDEE in its Spanish acronym), both adherents to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, warned about the increase in tension in their municipality. According to PUDEE, a group of 120 people from Tila and annexes went to Tuxtla Gutierrez to demand the return of the Municipal Council in Tila, which, it said, “was expelled by corrupt, murderous, kidnapping, perpetrators of division, drug addicts, prostitutes and alcoholism.” PUDEE detailed that this march was headed “by the indigenous teacher named Francisco Arturo Sanchez Martinez, son of Arturo Sanchez Sanchez, intellectual leader of paramilitary group Peace and Justice and nephew of Samuel Sanchez Sanchez, imprisoned (…) for the counterinsurgency conflict in 1996.” It said that “through political operators, truck drivers, concessioned transport operators and beneficiaries of the Prospera program from different different communities, they are causing provocations through marches, roadblocks, violence, threats and insults against civil society, against the ejidatarios and ejidal authorities (…) to justify the entrance of the public force.”

It is worth noting that the lands of Tila ejido were recognized by presidential resolution in 1934. In 1966 an attempt was made to modify the plan to deliver 130 hectares to the municipal presidency. In spite of “amparos” (appeals on the grounds of unconstitutionality) in favor of the ejido, they were not being fulfilled. In 2015, the villagers expelled the official authorities, recovered the lands where the municipal presidency was and declared their autonomy. More recently, the Congress of Chiapas authorized the change of seat of the municipal presidency to El Limar, and it is for this reason that the ejidatarios believe that the mobilizations against them have intensified.

From the women’s front

In May, the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women and Femicide held a protest in Tuxtla Gutierrez against the absence of medicines, equipment and health personnel. It left Rafael Pascacio Gamboa Hospital, where, two days earlier, five nurses concluded a 23-day hunger strike, and went to the local Congress, “to give testimony of the human and social cost generated by state authorities in deepening the crisis in the health system that affects thousands of people.”

In May and June, organized groups of women, following up on the Declaration of Gender Violence Alert (GVA) against Women declared in November 2016 in the state, pointed out “some urgent observations to see to as the increase of violence against women and femicide in different regions of the state continues to indicate the lack of capacity of the institutions in the state to react and respond to the measure.” They denounced, among other things, the “inability of institutions”, “no progress and setbacks in [its] implementation”, as well as “lack of transparency” and “political will” (see Focus).

OAXACA: Land and territory, root of multiple processes

For almost a decade, the federal and state governments have announced a number of projects for Oaxaca, including 67 hydroelectric dams, 21 wind farms, 299 mining concessions, 2 gas pipelines, real estate construction for tourism, as well as the recent announcement of the implementation of the Special Economic Zone of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Attacks on community and environmental defenders have been reported. Oaxaca is currently in the top places for aggressions towards this type of players.

In June, during the forum “Special Economic Zones and Implications in Community Life and the Environment,” about 50 social and civil organizations rejected its implementation in “the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca and elsewhere in the state.” They pointed out that the SEZs are intended to generate employment, but that through the implementation of mining, wind and gas pipelines, among other things, they would end communal life and promote extralegal and paramilitary violence.

On other fronts, in the city of Oaxaca, the fourth meeting of women activists and human rights defenders took place in June, with the participation of about 70 women from different regions of the state. The meeting encouraged the design of a comprehensive feminist protection strategy and the strengthening of alliances between different struggles. It should be noted that in 2012, the Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity registered a total of 48 attacks against women defenders in Oaxaca while in 2016, that number rose to 320.

In another case, in July, the bus carrying members of the June 19th Nochixtlan Committee of Victims for Justice and Truth (Covic in its Spanish acronym), as well as teachers of Section 22 of the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE in its Spanish acronym) to Mexico City to participate in the commemorative march for the 34 months of the disappearance of 43 students of the Raul Isidro Burgos Normal Rural School, Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. Covic was created to clarify what happened during the eviction on June 19th, 2016, when federal and state police officers attacked parents and Section 22 teachers blocking the road at Nochixtlan, in repudiation of the educational reform, an operation in which eight people died and 108 were injured. The official version of the facts assures that the police were not armed or were not the first to shoot at the population. However witnesses and even police officers who participated in the operation gave different testimonies from those offered by the police.

Furthermore, with a total of 82 victims, 10 homicides, 69 files of investigations still open, and 28 complaints filed so far in 2017, Oaxaca is the fourth nationally in attacks on journalists. Although a Specialized Unit for Crimes Committed against Freedom of Expression began to operate, the Attorney General of Oaxaca indicated that the unit faces operational problems due to budget cuts.

In view of a panorama where 1,990 femicides have been committed in the last 18 years, the request for a Gender-Based Violence Alert, which the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office of Oaxaca had submitted in July due to numerous cases of family violence, disappearance of adolescent females, femicides, possible trafficking in persons and other crimes committed on the basis of gender, was admitted.

GUERRERO: Bleak panorama

Caravan to the South-Southeast of the relatives of the 43 disappeared from Ayotzinapa in Chiapas, July 2017 © SIPAZ

In its report “Guerrero: Sea of Struggles, Mountain of Illusions”, published in the framework of its XXIII Anniversary in August, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center gives an account of how the bleak panorama that characterizes the state, has been getting worse. It explains the levels of violence that have been reached by “the strategic location of the state of Guerrero [which] has been exploited by large criminal groups that have settled at strategic points to take control of all the chemical processing of the poppy and control of land, air and sea routes of the drug.” It also denounced that “the void left by the institutions responsible for promoting the development of the countryside has been covered by organized crime that could easily enter the communitarian territories and offer narco crops as a viable option for their survival.”

Retrieving data from the National Public Security System (SESSNSP in its Spanish acronym), Tlachinollan mentions that from January to May 2017, 955 homicides were recorded in Guerrero and that, in May, Guerrero appeared as the most violent state in the country with an average of 7 murders a day. Another expression of violence has been the increase in enforced disappearances. Tlachinollan’s report stresses that “the formation of several groups of relatives of missing persons in Iguala, Chilapa, Acapulco highlight a problem that is not being addressed by the authorities.”

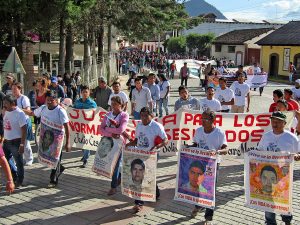

As for the most publicized case, on September 26th, 2017, will be the third anniversary of the murder of six people and the forced disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa, in Iguala, Guerrero. In June, their relatives started a caravan in the South-Southeast of the Republic so that “in every corner of Mexico, it is known that the Mexican State, although it continues to hide the truth, is responsible, and it will not be forgotten.” In this and other platforms the need to exhaust the four lines of research identified by the group of independent experts of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has been emphasized. The IACHR has expressed its concern about the weak progress. In this context, the relatives of Ayotzinapa, reported the criminalization, threats, aggressions, campaigns of defamation and espionage that they have had to face.

Caravan to the South-Southeast of the relatives of the 43 disappeared from Ayotzinapa in Chiapas, July 2017 © SIPAZ

In general, the defense of human rights is high risk in the state. In June, Tlachinollan denied the claims of the head of the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI in its Spanish acronym) that the organization would be involved in a diversion of public resources destined to Mountain communities, after the affectations of the storms Ingrid and Manuel in 2013. Tlachinollan stated that “Mexican authorities use slander and defamation against defenders who are uncomfortable to power, since they highlight the omissions of the State.” In July, civil organizations also denounced the authorities’ indolence to protect the members of the Jose Ma. Morelos y Pavon Regional Center for the Defense of Human Rights, which has worked for relatives and victims of enforced disappearances, arbitrary executions and forced displacement in Chilapa.

As regards freedom of expression, Tlachinollan emphasizes that the state “fulfills all the conditions to become a” zone of silence””. In 2016, the international organization Article 19 documented 26 assaults in Guerrero (fifth place nationwide). In addition during 2017, 22 aggressions against communicators have already been documented. State journalists have denounced that “in this climate of violence that prevails in Guerrero, the ineffectiveness of the institutions leaves everybody in Guerrero in total defenselessness. Anything can happen in Guerrero because the crimes go unpunished, so it is urgent that the investigating authorities show results.”

On a potentially more encouraging note, the Ministry of the Interior issued a Gender Violence Alert in eight municipalities in the state. Independently of the process coordinated by Conavim, the governor, Hector Astudillo Flores, had previously announced seven urgent actions to address all types of violence against women. It acknowledged that from 2009 to 2016 there were 744 cases of intentional homicides of women and girls and that since December 2010, when the crime of femicide was typified, 142 cases of femicide have been registered. Members of the Feminist Alliance of Guerrero questioned nonetheless whether Astudillo’s statements are part of a political and media ploy.