LATEST: Mexico – Indigenous issues on the political agenda again?

26/09/2017

ARTICLE: Against pain and fear: a cry of hope. Forum on forced disappearance

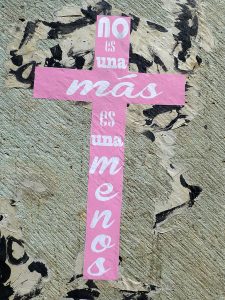

26/09/2017To date, 80 municipalities in 11 states in Mexico have established a Gender-Based Violence Alert (GVA) with the aim of promoting greater security for women and reducing the number of femicides that currently reach an average of seven women murdered per day throughout the country .

In August, in Mexico City, in the framework of the forum Swimming Against the Current: Context and Follow-up of Gender Alerts from Civil Society, Academia and the State, the lack of real political will of the authorities towards the implementation of public actions that allowed the protection of the integrity and life of women was reiterated. This is reflected in the lack of economic and human resources (with training and sensitivity on the issue), the lack of a comprehensive approach, excluding civil society participation in the definition, implementation and evaluation of measures, as well as in omissions of elements theoretically included in the GVA.

Other people and groups go further and even point out that it is a mere political simulation in order to co-opt women. In most of the interviews we conducted in the context of the preparation of this report, it was mentioned that the few actions and resources are primarily used for electoral and political purposes.

Understanding the problem

The concept of gender is an expression that seeks to reflect what “feminine” and “masculine” categories imply in society, for example the typical roles assumed by “men” and “women” in family, work or school, as well as the behaviors, activities and attributes that are considered appropriate for them.

Why is it important to think about this difference? Because everybody should have the same opportunities and the same treatment as we all share the same human dignity. However, there are strong “social differences and inequalities between men and women which come from learning, as well as the stereotypes, prejudices and influence of power relations in the construction of genders.” This is what gender violence means, which goes far beyond physical violence or in its extreme expression, femicide .

The Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, “Convention of Belem do Para”, ratified by Mexico in 1998, defines this type of violence as “any action or conduct based on gender that causes death, physical suffering, sexual or psychological harm to women, both in the public and private spheres.” The Citizen Observatory against Gender Violence, Disappearance and Femicide goes beyond this stating that gender violence can also occur on economic and patrimonial levels.

Expressions of gender violence

The high number of femicides in Mexico has already been mentioned. Of equal concern would be rape: 35 women report suffering rape every day, according to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH in its Spanish acronym). In addition, according to statements by the Ministry of the Interior in February this year, 67% of women in Mexico have suffered at least one violent incident in their lives, 47% of them victims of their current or last partner. Furthermore, according to the United Nations, one in five women in the country has been a victim of workplace violence.

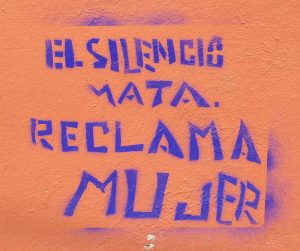

Moreover, these figures could be much higher because factors that can lead to their minimal expression are combined: on the one hand, there is a lack of information so that women can know and fully exercise their rights. Many do not know how to claim them or put them into effect, they do not know that there are laws that protect them and specialized agencies where they can denounce any type of violence, as well as bodies or organisms to which they can turn. On the other hand, many of them do not go to the authorities or defense agencies for fear of reprisals on the part of the aggressor, for fear of being left alone or being rejected by their families and communities.

In addition, those who do report are often confronted with responses that imply re-victimization or the wall of impunity. It is also important to highlight the lack of preparation of the justice system itself. In general, there is a shortage of specialized personnel and with the sensitivity required to deal with cases of gender-based violence. More specifically, of the 2,883 homicides committed in Mexico between January 2015 and July 2016, only 25% were investigated as “femicide“, according to the National Citizen Observatory of Femicide. Many of the agencies of the Public Ministry are unaware of femicide as a type of crime, a crime different to a murder felony, as well as the investigation protocol to be implemented in these cases. Moreover, the lack of an adequate register of gender-based violence limits the possibility of implementing relevant public policies and actions or of the effective scope required.

There are more subtle ways to limit women’s access to their rights: from 46.2% of people living in poverty in Mexico today, it has been observed that poverty affects women more than men. They also have less access to education (17% lack basic education and only 24% of enrolled women will complete a bachelor’s degree); and their access to health is not equitable either. The educational factor has a direct impact on their chances of access to decent work. If they find it, they will earn between 30 and 40 percent less than men in equivalent positions. Only 3.9% of women obtain jobs in management positions. All this results in a strong economic dependence: 87% of women are dedicated to the home after getting a partner, limiting their ability to make decisions due to lack of their own income, even in cases of abuse.

Normalization of violence against women and sexist culture

Mexican society is highly sexist and in it, men and masculinity are often valued over women and femininity. This patriarchal system is present in all spheres of everyday life, and in all strata of society, both rich and poor, indigenous or mestizo, and urban or rural areas. For the same reason, it must be observed that gender violence is a structural and cultural problem, which on a historical level has resulted in a normalization of male logic and domination through education, culture, the media and the institutions themselves.

It should be recognized that there has been some progress, something that can be perceived by the Diocesan Coordination of Women in Chiapas, which is celebrating 25 years of work, changes that have occurred from the family level, so some participants say: “Today my children grow up learning that they will not do as it was before, like their fathers, children learn that we have the same rights.”

In the same vein, the Feminist Observatory of Tuxtla said that, “before, family violence was not seen as a social problem, it was seen as the right of man over his family. Because those who exercised parental authority were men over all the women in the house – mother and daughters – even with beatings. Then – with the debate on the rights of women over their bodies – perceptions began to change, it became a public problem.”

What do the Gender Violence Alerts involve?

The General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence was approved in Mexico in 2009, the National Commission for the Prevention and Eradication of Violence against Women (CONAVIM in its Spanish acronym) was created, seeking to promote reforms at state level. The General Law already defined the gender violence alerts in article 22: “It is the set of emergency governmental actions to confront and eradicate femicidal violence in a given territory, and / or the existence of a comparable offense that prevents the full exercise of the human rights of women in a specific territory (municipality or federative entity); violence against women can be exercised by individuals or by the community itself.” However, they only began to be implemented in 2015. The State of Mexico was the first to bring them into effect in July of that year.

As most of the organizations interviewed pointed out, GVAs tend to be influenced by the pressure of civil society to obtain them, with all kinds of actions (including public complaints, press conferences, marches, performances, information and training spaces, etc.). For example, the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women in Chiapas started working in this direction since 2013; GVA was not obtained until November 2016.

GVAs are usually adapted according to the municipalities or states in which they are to be implemented. However, they usually follow the same time-line: first, an inter-institutional and multidisciplinary group with a gender perspective is formed to follow up on what has been proposed. Second, preventive, security and justice / reparation actions are formulated with indicators that show progress. Finally, it is made public.

Chiapas – “progress in recognition of the problem”

In Chiapas, the Declaration of Gender Violence Alert was obtained in November 2016. The first objection of civil organizations was the limited number of municipalities in the state that it intends to cover. Organizations like Kinal Antsetik consider that at least obtaining the declaration involved “progress in recognizing the problem”.

Since the declaration, organized groups of women have questioned “the lack of capacity of institutions in the state to react and address the urgent measure of alert.” They denounced, among other things, the “inability of state government institutions”, “zero progress and setbacks in the implementation of the GVA,” the “lack of transparency” in accountability, and, in short, the authorities’ “lack of real political will.”

Broadly, they consider that the GVA does not reflect a critical gender perspective, but rather a classic duality between masculine and feminine, and as the Center for Women’s Rights of Chiapas (CDMCH in its Spanish acronym) points out, “women” are presented as victims and object of protection, not as independent subjects. In more specific aspects, it denounces omissions of the bodies that receive the victims: for example, there is no channeling of health services to the investigative bodies when identifying situations of abuse. There are reports of victims of rape, including minors, who were denied termination of pregnancy despite the legislation prevailing in these cases. As for the investigation, the protocol of the GVA is not fulfilled because it does not yet try to differentiate homicides from femicides. The CDMCH also questions the fact that services are not accessible in remote communities and there are no translators in indigenous languages or specialized staff.

Guerrero: a policy that appropriates the discourse to avoid it?

“Mexico, Seven killed daily. Every four minutes a woman or a girl is sexually abused. Many disappearances. #Ya Basta “© SIPAZ

According to investigations of the Autonomous University of Guerrero, the state of Guerrero has been among the top places of violence against women for more than 20 years. The Observatory of Feminine Violence “Hannah Arendt” counted a total of 1737 women killed from 2013 to 2016, 47% of them in Acapulco. For its part, from June 2016 to May 2017, the Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center documented 269 cases of violations of women’s human rights, particularly indigenous women, peasants and mestizos from the Guerrero Mountain region. The types of violence denounced are diverse: from psychological, economic, physical, sexual, patrimonial, to femicide.

In June 2017, the Guerrero Association Against Violence Against Women (AGCVIM in its Spanish acronym) petitioned the National Commission to prevent and eradicate violence against women (CONAVIM in its Spanish acronym) to declare a GVA. In an interview, Marina Reyna Aguilar, president of the AGCVIM, told us that, knowing of this request and its forthcoming acceptance from CONAVIM, the state governor, Hector Astudillo Flores, tried to get the upper hand to win political kudos. Two days before the official declaration (issued from the federation), he convened a meeting called “The government of Guerrero, committed to the rights of women”, in which he declared on behalf of the state government a gender alert independently of the decision of the SEGOB. It should be mentioned that until then the governor was reluctant to declare the GVA. In May 2016, when he was questioned on the subject, he declared that this could create great damage to the state, affecting tourism, the main source of jobs and foreign currency for the people of Guerrero.

However, despite the fact that it made a first move, the Guerrero government has so far not taken any concrete action to prevent or combat violations against women. In addition, it has not met the deadline set by CONAVIM to deliver its work plan and schedule. Several women’s rights defenders in Guerrero have denounced the government’s lack of compliance and interest in launching the alert. “What is happening is that in the Government of Astudillo there is a whim for not accepting the reality that exists in Guerrero, where violence against women is already something daily, and that nothing is done to prevent it and less to punish those responsible”, said Marina Reyna Aguilar.

Oaxaca – trust the alert?

Just a few weeks ago, the National System to Prevent, Attend, Punish and Eradicate Violence against Women (SNPASEVM in its Spanish acronym) admitted the request presented by the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office for the declaration of a GVA in Oaxaca. The Ombudsman’s office called for ensuring the safety of women, taking into account the fact that since 2013 they have reported increasing violence rates, reporting 1,990 femicide cases in 18 years, with 70 in the current administration of Alejandro Murat. The process began with the formation of an interdisciplinary group that will present a report to the Secretary of the Interior (SEGOB), who will review and notify the State Government of what is defined, which could take up to four months.

The coordinator of Legal Issues of the National Institute of Women (Inmujeres in its Spanish acronym) acknowledged that they can leave the learning process at a national level due to the high complexity of the state with more than 570 municipalities and its great cultural diversity, “with certain areas where the roots of violence towards women is decisive and is linked to expressions of agrarian, inter-ethnic or interreligious conflicts.”

In statistics from the Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity, documented by governors, the figures show an interrelated trend between femicide, intra-family violence, sexual violence, disappearances and suicides that have been increasing. In response to the declaration, this organization drew attention to the factors that contribute to gender violence, which depend heavily on the context of each region and its interrelations with other social phenomena (including the migratory dimension). In its 2016 report, the Consortium stated that “the State is working, it is creating instances, making collaborative agreements to address the problem, but it is not a question of addressing but rather of understanding in order to solve it.”

Another aspect mentioned in Oaxaca and also omitted in other GVAs is the lack of coverage for deaths of people of another gender. In 2016, 160 violent deaths of transsexual people were reported. Even more than women, they suffer from normalized physical violence, transphobia and homophobia in the form of “hatred” from society as well as public services towards people with a different gender identity or with a different sexual preference.

Also in Oaxaca, civil organizations emphasize another issue of particular relevance to all GVAs, the need to work on prevention, in particular with young people. This would reduce physical and psychological violence, as well as helping young women in the face of the difficulty of choosing a life of their own in spite of family and social pressures. Also, it should be remembered that “talking about women’s rights does not mean making men invisible”, says Consorcio. In fact, men are also affected by gender-based violence against women, insofar as those affected can be members of their family. At the national level, women’s organizations stress that it is important to work with men, to invite them to invent a new masculinity and to support the rights of women.

Another tool

GVAs are not the panacea, but an additional tool to set up bases and review progress. In each of the states where they have been implemented or are in the process of being questioned, there are questions that could allow the design of more comprehensive strategies, recognizing that this is a complex structural problem with strong cultural roots. Designing finer diagnoses, updated databases and monitoring and follow-up tools, sensitizing media and working on permanent campaigns with a gender perspective, a human rights and intercultural approach focused on society as a whole (with particular emphasis on education systems), to train and professionalize the personnel of the institutions responsible for the care, prevention, investigation and punishment of violence against women, in addition to guaranteeing these institutions the resources necessary for their proper functioning, to continue to adapt laws, civil and criminal codes, etc. are some of the ideas that have been appearing so that women in Mexico can effectively have access to a life without violence and without fear.

How can we all contribute to a Mexico without gender-based violence?

Men, women, or any other gender identity, you can also make a difference:

- denouncing if you are affected, if it is your neighbor or a person in the street.

- informing yourself: looking for information about independent resources like the initiatives of citizen observatories.

- demanding that the state reduce violence by providing the necessary resources for prevention institutions, judicial processes without impunity and training of employees in public services

- solidarity with the struggles of everyone against repression and violence in all its forms.