LATEST: Mexico at Multiple Crossroads

14/07/2018

ARTICLE: “This little light is for you (…) Take it and put it together with other lights” – International Meeting of Women in Struggle

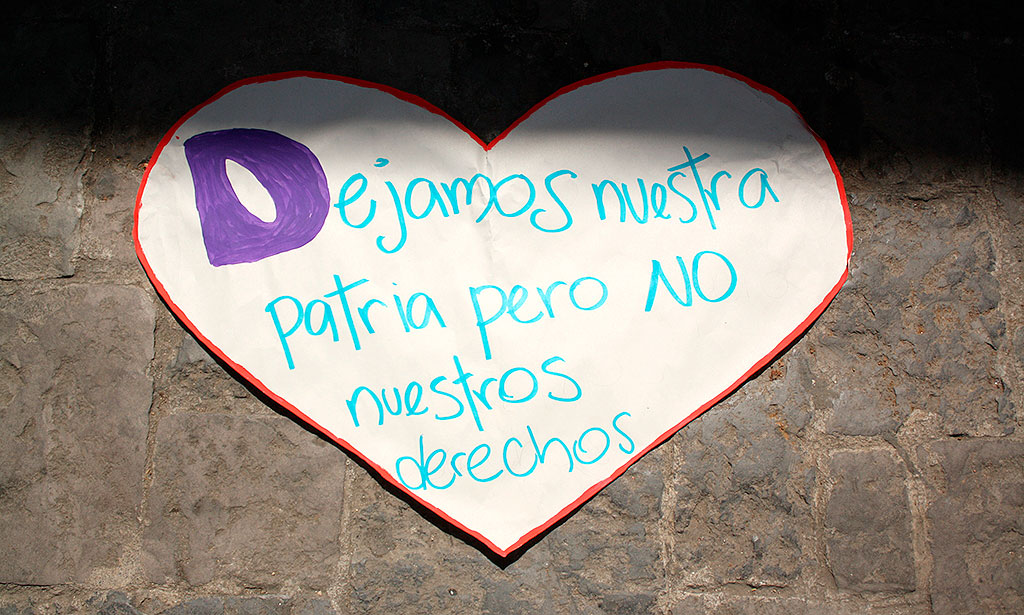

14/07/2018The worldwide migration crisis is undeniable and has been exacerbated by laws and agreements focused only on the control of the borders of the countries that receive migrants and refugees, and not on respect for human rights, a value that all nations say they share.

Migration is defined as the relocation of a person or group of people to change their place of residence, be it from one country to another, or within the same country. There are different factors that motivate people to migrate: political, economic, social, cultural, and war, among others.

International legislation exists that attempts to protect the human rights of migrants, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Migrants, which entered into force in 2003, once approved by 20 countries and which, curiously, neither the Union European Union or the United States has ratified. The countries that have done so are fundamentally the countries of origin of the migrants, who are concerned about the situation of their citizens, who take this option and take a “dangerous step” determined to search for improvements in their quality of life.

One of the busiest borders in the world is that between Mexico and the United States. We cannot know for sure how many people try and successfully cross it every year. However, as an indicator, the US Border Patrol reported 341,084 arrests of migrants at that border in 2017, which is a decrease compared to 611,689 in 2016. Several factors could explain the apparent decrease in migrant flow: the change in the discourse and immigration policy of the United States since Donald Trump came to power, and/or the greater control of the southern border of Mexico when a large part of the migrants enter through there could be two of them.

Hardening of United States discourse and immigration policy

The historian James Truslow Adams defined in the idea of the American Dream in 1931 that “Life should be better and richer and fuller for all people, with an opportunity for everyone according to their ability or their work, regardless of the social class or the circumstances in which one is born”, rooted in the American mentality as the land that offers opportunities under conditions of equality, and in which the success of the people is based mainly on their effort. It is this that leads many migrants to try to live it with the idea of improving the living conditions of their families. However, that idea that makes them travel thousands of kilometers has been increasingly meeting with a devastating reality.

For decades, the US has progressively tried to curb the migrant flow, so this trend is nothing new. For example, according to data from the Mexican Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB in its Spanish acronym), the deportations of Mexicans in the two periods of Barack Obama’s government (2009-2016) reached a total of almost three million, making him the president who has deported most Mexicans to date. This trend continues regardless of the origin of the migrants.

Complying with what was promised during his presidential campaign, the current president of the United States, Donald Trump, has hardened his discourse and the immigration policies of his country against frontiers that he considers “weak“. In his first year in the White House, he canceled the Deferred Action Program (DACA), created by Obama in 2012, which protected undocumented children who arrived in the country.

In January 2017, Trump ordered the construction of the wall with Mexico and increased the number of immigration officers, which, according to The New York Times, “establishes a new vision to fortify the borders of his country and increase efforts to deport some of the 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States, which includes the recruitment of more state and local officials who will be in charge of tracking them and also detaining them.” It also announced new rules that promote the immediate deportation of people who have been convicted or accused of a crime, without specifying what type or how serious.

François Crépeau, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Migrants’ Human Rights, said that “their management of irregular migration is very similar to anti-alcohol policies during the years of prohibition or the war on drugs. With programs of zero tolerance, criminality appears, a clandestine market and many rights are violated.” Its migration policy was also condemned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Raad al Hussein, who stated that in the United States a “broader and more coherent” leadership is needed to confront “the recent rise of discrimination, anti-Semitism and violence against ethnic and religious minorities.” “Denigration against entire groups, such as Muslims and Mexicans, and false accusations that immigrants commit more crimes than Americans are harmful and fuel xenophobic abuses,” he said on the occasion of the presentation of his annual report for 2017 before the Human Rights Council of the UN.

Within the United States, there are many voices that highlight the harshness and consequences that Trump’s migration policy is having in the immediate future and that will be reflected in the long term. In March 2018, the American Association of Lawyers for Immigration (AALI) published a report entitled “Deconstructing the Invisible Wall” in which it warns that the measures taken by the US government, since Trump came to the Presidency, are an “invisible wall” from which the country will take years to recover, and which are slowing down and even stopping the legal immigration of the country.

Neither the hardening of the discourse nor of migratory measures or even the promise of building a border wall seem to have managed to completely stop the intensity of the migratory flow. According to the Observatory of Legislation and Immigration Policy, which recently published data from the Customs and Border Protection Office (CBP), “in April of this year, Border Patrol agents detained 50,924 immigrants, which represents an increase of 223% with respect to the same month of the previous year, when there were 15,766 arrests.” It should be noted, however, that according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the number of migrants who died trying to enter the United States increased by 3% in 2017 when searching for more remote and dangerous routes for entry.

Mexico: human rights discourse, militarized migratory practices that do not stop the growing violence towards migrants

At the end of March 2018, some 1,500 migrants who fled their countries due to internal violence, started the Caravan “Viacrucis Migrante 2018”, which gained wide media coverage, given the ire of the American president it aroused. Donald Trump used them as an example of the weakness of his country’s borders, called to block them and even mobilized troops on the border. He threatened that “the source of benefits of NAFTA (…) is at stake, as well as foreign aid to Honduras and other countries” that permit this situation.

In April, the Mexican government announced that it will multiply the numbers of the National Gendarmerie on the southern border, but, while maintaining its commitment to protect the human rights of migrants. 84 organizations, collectives and networks of 23 Mexican states demanded that the plan be canceled. They consider that “it puts the integrity of people in the context of human mobility at serious risk, which will undoubtedly result in a new increase in violence, xenophobia and criminalization of migrants, refugees and those who defend them, as well as the population in general.”

They also denounced that “this decision of the Mexican government shows that there is no comprehensive, defined or clear approach to human movement, persisting in a strategy that criminalizes Central American forced migration. Rather, it takes place exactly on the same days as the deployment of the United States National Guard on our northern border to replicate this border reinforcement between Mexico and Central America. This decision, taken last April 3rd, is opposed to the message issued by President Peña Nieto in response to Trump on April 5th, in which he made an alleged call for national unity in defense of the dignity and sovereignty of Mexico, a speech that was applauded by wide social sectors of the country, without contemplating concrete actions to revert the decision of Trump.”

Shortly after, the Viacrucis dispersed in different groups upon arriving in Mexico City: some decided to stay in Mexico and others chose to continue towards the US border. 228 people of the Viacrucis were allowed into the United States later, without guarantee that the asylum request will be resolved in their favor. On the Mexican side, fifteen members of the Caravan began a hunger strike in Sonora due to the delay in obtaining legal stay permits, something to which the National Institute of Migration (INM in its Spanish acronym) had committed.

In May, various networks and organizations defending the migrant and refugee population expressed their “deep indignation, concern and estrangement in the face of information that has circulated in various media outlets, signaling an agreement in dialogue to convert Mexico into a filter for asylum seekers to the United States and as an immigration detention center.” They noted that it has been pointed out that “Mexico would have the role of a “safe third country”, which means that there will be an increase in arrests not only of migrants, but above all, of asylum seekers fleeing the violence in their countries and who intend to seek refuge in the US.” They demanded that “the dialogue with the United States be suspended on this matter until all the information is public, and until the new government that emerges from the ongoing Federal electoral process assumes its functions. Human rights cannot be negotiated as a bargaining chip in any commercial treaty.”

For several years, the Mexican government has been implementing the Southern Border Program, which aims to “protect and safeguard the human rights of migrants who enter and transit through Mexico, and order international crossings, to increase development and security of the region.” It proposes that Mexico and Guatemala work together to make the border a “safer, more inclusive and competitive zone.” It is important not to forget that in 2012, as Proceso magazine published (“Marines … on the southern border of Mexico”), “two hundred US soldiers, supported by helicopter gunships and heavy weapons, carry out operations in Guatemala, right on the border with Mexico. Its objective: to fight the cartels of Sinaloa and Los Zetas, organizations that settled in Central America. Officially it is a joint operation between the armies of the United States and Guatemala, called Hammer. However, it is the Southern Command of the US Navy that directs the actions, while its soldiers have privileges and immunity in cases of destruction of real estate or civilian deaths.”

Meanwhile, in recent years, crossing Mexico has become one of the riskiest parts for migrants whose goal is to reach the United States, particularly for women. They find in Mexico a country that exerts a brutal violence towards migrants. A study conducted by the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico (ITAM) states that “violence against migrants in Mexico has reached unprecedented levels; kidnapping and murder have been the maximum expression of that violence, but not the only one. On the other hand, there is sufficient evidence to affirm that the criminal links of Mexico have been extended and connected with other groups already existing in some Central American and American localities, affecting both Central American and other migrants in international transit, as well as Mexican migrants.”

Martín Iñiguez Ramos, specialist in Migration of the Ibero-American University, warned that in states such as Chiapas, Tabasco, Oaxaca and part of Quintana Roo, the National Institute of Immigration (INM in its Spanish acronym), together with other institutions, has undertaken “a hunt for immigrants” He pointed out that the Southern Border program must go because it is absolutely violating human rights, in addition to the fact that the General Immigration Law of 2011 must contemplate new humanitarian visas and the figure of the refuge.

Migrants or…refugees?

The United Nations Agency for Refugees (UNHCR), makes a distinction between migrants and refugees, the latter being people fleeing armed conflict or persecution and whom international law protects with certain measures, such as the fact that they should not be expelled or returned to situations in which their lives and liberty are in danger. On the ther hand, migrants choose to move to improve their lives in the hope of finding work, or access to education, as well as family reunification or other reasons. Making this distinction is important, as countries treat migrants according to their own legislation, while asylum and refugee protection standards, as defined in international law, are applied to refugees.

This nuance would oblige us to recognize that a large part of those now considered migrants from Latin America and, in particular, from Central America, could correspond to the profile of asylum seekers. The latest report of the World Health Organization (WHO) on violence in the world shows that the countries of the Latin America region have the highest rates of homicides on the planet. “In 2012 (the last year for which there is data) 165,617 people in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean were killed. Three quarters of these homicides were perpetrated with firearms. The regional homicide rate translates into 28.5 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, the authors of the report calculate. It is a rate that quadruples that of the rest of the world and is double that of developing countries in Africa.”

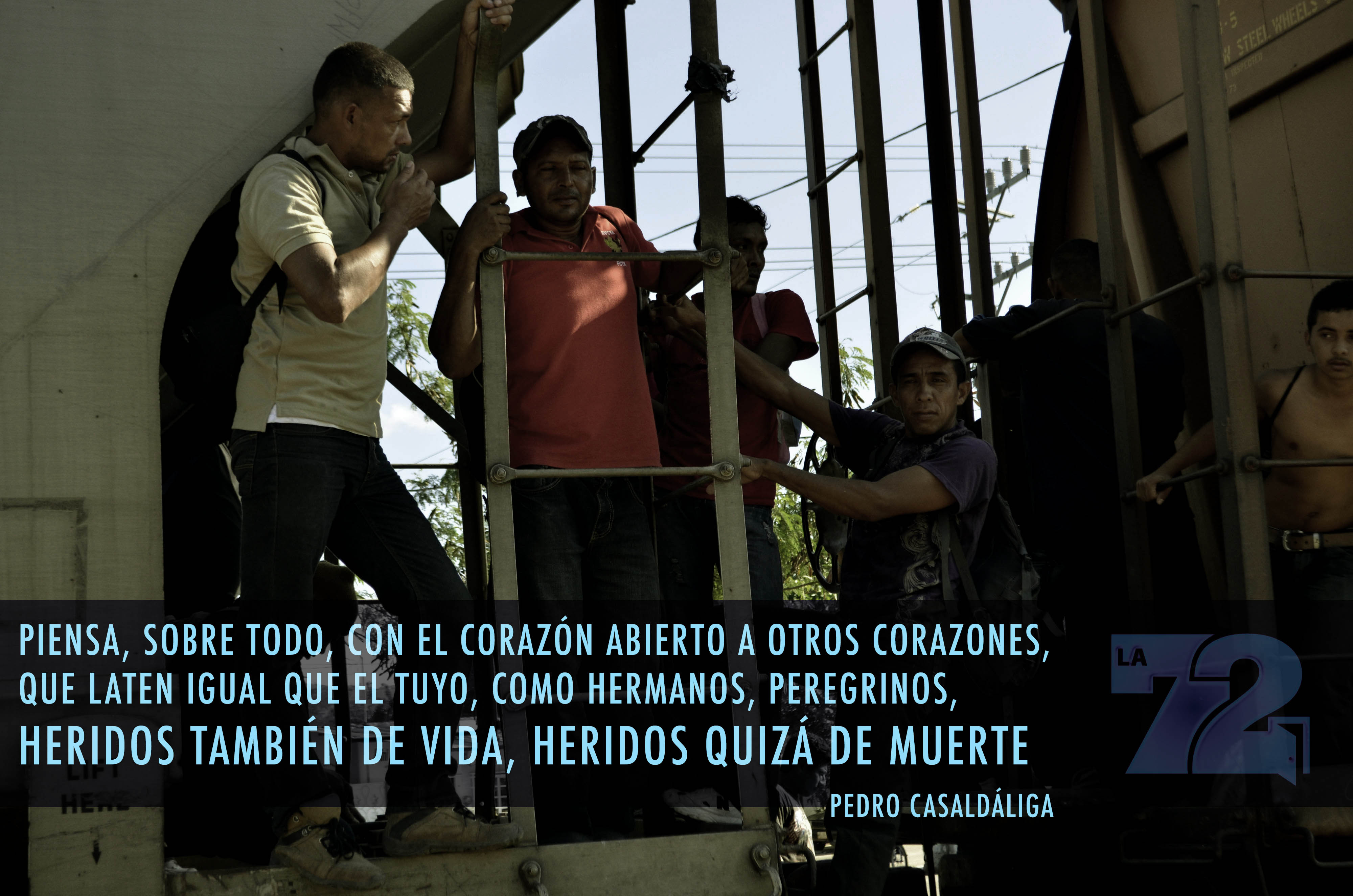

“Think, above all, with an open heart to other hearts, that beat like yours, as brothers, pilgrims, also wounded in life, perhaps mortally wounded”, La 72, Tenosique, Tabasco © La 72

A 2011 report entitled “Crime and Violence in Central America. A Challenge for Development” published by the Departments of Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction and Economic Management in the Latin America and the Caribbean Region that belong to the World Bank warned that “Crime and violence constitute the key problem for development of the Central American countries.” So we could say that violence leads to an increase in poverty since a favorable economic situation develops under conditions of peace and stability. Perhaps it would be good to ask ourselves if many of the Central American migrants who try to cross Mexico to achieve better living conditions are not really “refugees” fleeing situations of direct violence or even situations of poverty generated by violence in their countries. According to UNHCR data, “58% of people from the so-called northern triangle (El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala) can be potentially accredited refugee status.”

The United States, Mexico and the “migrants vs. refugees” dilemma

It should be noted that US law states that asylum seekers must be received and it must be decided if they are to be taken to an immigration centre or given an electronic tagging device to go to their destination until such time as their cases are decided. The Immigration and Citizenship Services (USCIS) decide whether the person’s fear for seeking asylum is credible or not. In cases where it is not condidered so, the deportation process begins. The Donald Trump government maintains that fraud for obtaining asylum permits is growing. Justice Department statistics reveal that in the 2016 fiscal year, 65,218 asylum requests were received, of which 8,726 were granted.

As for Mexico, since 2016, the Mexican Constitution recognizes in Article 11 that “every person has the right to seek and receive asylum. The recognition of refugee status and the granting of political asylum will be carried out in accordance with international treaties.”

In 2017, there were 14,596 asylum applications to Mexico. According to the report of the Mexican Commission for Aid to Refugees (COMAR in its Spanish acronym), it is still pending to solve a little more than half, 7,500 719, which shows the difficulties for thousands of people to access this condition. In February of this year, members of the Grupo Articulador Mexico (GAM) reported that “last year COMAR recognized only 1,907 people with refugee status and 918 received complementary protection, less than 20 percent of the applicants that year.” It regretted that the ability to receive, process and provide international protection to people who need it has not increased in the same proportion as the asylum requests to Mexico in the last three years.

The UNHCR said that “on the one hand, the Mexican government promotes global agreements in favor of migrants, such as the Convention on the Right of Migrants and their Families, but on the other, it closes the doors to thousands: it only has 0.048 refugees for each thousand inhabitants, while nations such as Lebanon or Uganda have 173 and 24, respectively.”

In this same line the Social Observatory of Human Rights and Migrations in the Southern Border of Mexico in its bulletin Derribando Muros [Breaking down walls] states that “Mexico, as a country of origin, transit, destination and return of migrants, lacks a comprehensive immigration policy that responds to the different facets of migration. In response, the Mexican state has imposed a policy of detention and, from the perspective of civil society organizations, this policy has resulted in immeasurable abuses and violations of the human rights of migrants, particularly those from Central America.”

Notes:

[1] Information system focused on collecting, reviewing and analyzing information on migration policy and human rights in the United States-Mexico-Central America region and which is a project of El Colegio de la Frontera Norte with support from the National Human Rights Commission.

[2] Central American Migration in Transit through Mexico to the United States. Diagnosis and Recommendations. Towards an Integral, Regional Vision and of Shared Responsibility. ITAM 2014.

[3] The GAM is made up of the American Friends Service Committee, Asylum Access Mexico, the Casa del Migrante de Saltillo, the Fray Matías de Cordova Human Rights Center, the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights, the Refugee House Program, Without Borders and the International Coalition against Detention

[4] The Digna Ochoa Human Rights Center A.C., Human Rights Center Fray Matías de Córdova A.C., Link, Communication and training A.C., Initiatives for Identity and Inclusion A.C., Mesoamerican Voices. Action with Migrant Peoples.