LATEST: Pressured by Trump, Mexico takes measures to curb migration to the United States

27/09/2019

ARTICLE: Earthquakes – Community Reconstruction as an Alternative Route

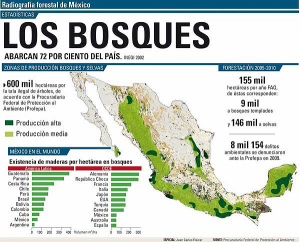

27/09/2019Currently, 30 to 35% of Mexican territory is covered with forests and jungles. Despite having great natural wealth, Mexico suffers from one of the highest deforestation rates on the planet.

A great variety of plants and animals, as well as many indigenous and rural communities, are at risk due to the accelerated destruction of their ecosystems. Frequent neglect, corruption, and government complicity have allowed this problem to progress and deepen.

Mexico: a great, overexploited natural wealth

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Mexico is considered to be one of the five countries in the world considered as mega-diverse. Together these five countries are home to 60 to 70% of the total biodiversity of the planet.

Until the mid-1970s, forests and jungles in Mexico were considered property of the State, that should contribute to the social and economic development of the country. The government created semi state-owned companies and granted concessions for 25 years and sometimes up to 60 years, to wood and paper companies. At the end of that decade in various regions of the country, local communities organized and achieved a significant change: forest resources began to be managed by communities and ejidos (communal lands), thus leading to the creation of Community Forest Enterprises (CFE).

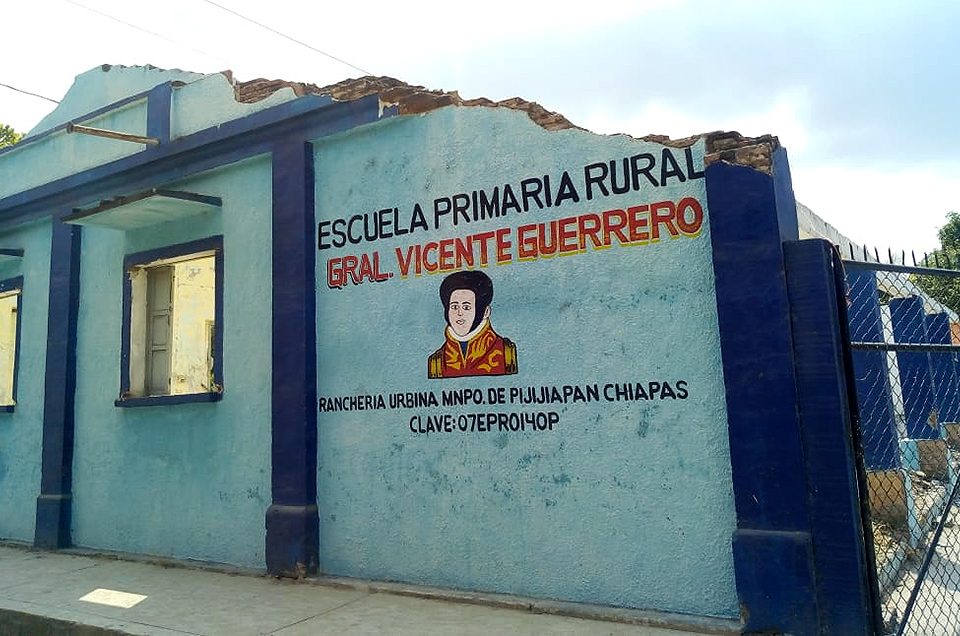

Today, according to the INEGI, 80% of the country’s forests and jungles are under community control (ejidos and agrarian communities), made up of around 8,500 CFEs. The CFEs, thanks to the legal sale of wood, have generated permanent jobs and have allocated part of the profits to public projects, such as schools, clinics, and infrastructure for drinking water. Unlike companies, communities are generally more aware of the importance of conserving their natural resources beyond immediate gain. Currently between 13 and 15 million peasants and indigenous people in Mexico live in communities that are located in forests and jungles. Some 2,400 ejidos and communities are looking for ways to have a rational exploitation of these ecosystems and at the same time conserve the enormous biological wealth they host, through Good Community Forest Management (GCFM).

Despite having successful cases of community management of forests (Sierra Norte in Oaxaca or “Tierra y Libertad” in the municipality of Villaflores, managed by the authorities of La Sepultura Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas), and having created their own surveillance systems with forest guards, the rates of deforestation suffered by Mexico and the retreat of their forests are more than cause for concern. The deterioration of forests, illegal logging, fires, pests, and climate change are finishing off forests and ecosystems in Mexico.

In several areas, the extraction of timber is far superior than that of the ability of the forests to regenerate. Overexploitation has different sources among which clandestine logging and private logging stand out. The extraction of firewood is usually considered free access and there are rarely internal rules that limit the use of wood for it. The consumption of firewood remains high and constitutes around 7% of the total primary energy consumed in the country (FAO).

Mexico: a world leader in deforestation

Globally, Mexico ranks fifth in deforestation, although some measurements place it in third place, next to Haiti and El Salvador. According to an analysis of the Center for Social Studies and Public Opinion (CESOP in its Spanish acronym) of the Chamber of Deputies, between 90 to 95% of the Mexican territory is deforested. A great variety of flora and fauna species that depend on Mexican forests is at risk of extinction. According to data from the Geography Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM in its Spanish acronym), 500,000 hectares of forests and jungles are lost every year.

According to the National Forest Program 2013-2018, deforestation occurs mainly in Michoacan, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Mexico State, Hidalgo, Veracruz, and Guerrero. Deforestation is caused primarily by human action, the conversion of forest into areas for agriculture and livestock, as well as the high demand for wood. This phenomenon is related to the increase in population density. Deforestation has also been increasing due to agricultural revolutions that have led to the development of methods and techniques with greater intensification of land use.

Deforestation: alarming environmental impacts

The FAO’s report “The State of the World’s Forests” in 2018 states that deforestation is the second most important cause of climate change after the burning of fossil fuels and accounts for almost 20% of all greenhouse gas emissions.

Deforestation leads to a multitude of negative environmental impacts. The loss of trees, which retain soil with their roots, means that after heavy rains water erodes the soil into rivers, causing landslides and floods. The sediment in rivers is increased which drowns fish eggs, causing a decrease in hatching rates. When the suspended particles reach the ocean, they cloud the water, affecting coral reefs and costal fishing. Tree felling has an adverse impact on the fixation of carbon dioxide (CO2) as well. Deforested regions tend to have more soil erosion and often degrade to non-productive land. Specialists also agree that deforestation amplifies the damage caused by meteorological phenomena such as hurricanes.

Illegal logging: a silent crime

According to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), at least 70% of the wood sold in the country has an illegal origin, in a context of widespread impunity. On a legal level, illegal logging is not classified as a federal crime. Nevertheless, the federal norm establishes that a penalty of one to nine years in prison, and 300 to 3,000 days of fine, will be imposed on those who disassemble or destroy natural vegetation, cut, uproot, tear down or cut trees, or change the use of forests. However, according to open data from the former Attorney General’s Office (PGR in its Spanish acronym), from 2000 to 2018, very few investigations were opened for breach of said rule (53 in Oaxaca and 50 in Chiapas). In the federal Congress, legislators have presented various initiatives to criminalize illegal logging. Despite this, even when they were approved in the Senate, most of the initiatives were frozen in the Chamber of Deputies.

Leticia Merino Perez, from the Institute for Social Research (IIS in its Spanish acronym) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) denounced that, “the seizures of the Federal Attorney’s Office for Environmental Protection (PROFEPA in its Spanish acronym) reach only 30,000 cubic meters of wood, compared to 14 million cubic meters that are illegally extracted.” Illegal production and trade are a product of improper regulation and its discretionary application, and by corruption and lack of supervision in commercial channels. It should be stressed that illegal logging is a multi-billion dollar business, its colossal annual profits reaching between 10 and 15 billion dollars globally, according to the “Justice for Forests” report of the World Bank.

Cesar Suarez Ortiz, Bachelor of Political Science and Public Administration from UNAM, explains that one of the main actors that has positioned itself as responsible for illegal logging in Mexico is organized crime. Organized crime groups have diversified their sources of income to other activities beyond drug trafficking, one of them being the sale of wood. The production and sale of drugs fell to second place to give rise to the increase in the illegal markets of natural resources, among others.

Illegal logging is a respond to a national demand of 20 million cubic meters of wood per year, while less than seven million are produced in the country. This means that Mexico also has to import wood, part of it illegal. The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) revealed, for example, the existence of a criminal network of illegal timber trafficking, extracted from the tropical forests of the Amazon in Peru, whose main buyers are Mexico, China, and the United States. The investigation titled “The Moment of Truth” explains that illegal timber is stolen from unauthorized areas, including forests and protected areas, territories of native communities, and private property. The government of Peru, says the EIA issues false permits or includes geographically referenced trees that do not really exist or their location is so remote that their extraction is not viable. So with false permits, “trees come into existence on paper and therefore ‘legitimate’ transport authorizations can be issued.” Bribes and a black market for seemingly legal documents allow merchants to launder illegal timber. The exporters of these products then argue that they bought them “in good faith,” despite the fact that multiple investigations have shown – even with undercover videos – that this is not the case.

The EIA emphasizes that “as long as a Forestry Law is not approved and applied that prohibits the entry of illegal timber and requires Mexican importers to carry out due diligence to verify the legal origin of the products they import, the flow of illegal timber will continue to cause negative effects on the environment and communities that depend on forests.”

Who are the lumberjacks in Mexico?

Beyond large-scale traffic, Hector Narave Flores, a professor and researcher at the Faculty of Biology at Veracruz University, explains that it is in “municipalities with a high level of marginalization where people need economic alternatives where, unfortunately, wood remains the alternative for some families.” According to a group of lumberjacks interviewed by the newspaper El Sol de Cordoba, they say that in exchange for 240 pesos – more than twice the current minimum wage – they will work for several hours to accumulate as much wood as possible. Four laborers can be paid with the sale of only one of the trunks they deliver.

“People who are dedicated to logging are still poor, so what is understood is that they are employees of people who profit from misery and those who profit are intermediaries who buy the product at the price that is next to nothing so that people are cutting daily, but they only earn enough to eat,” said one federal worker from the state of Veracruz anonymously.

He states that the industries that profit from wood are already identified by PROFEPA and it is used for the manufacture of pallets and boxes to transport vegetables. “Trees that have been growing for 80 years become a product that is used only once and is going to be thrown away,”.

Ecocide, between impunity and restorative sanctions

Although at the macro level the smuggling of trees is practically “untouchable” at the micro level, sanctions are occasionally seen. For the first time, in August 2019, the State Prosecutor’s Office of Chiapas reached a reparatory agreement against two lumberjacks accused of ecocide in the Tonala area. They will have to plant 3,000 ceiba trees and clear the riverbed of the Zanatenco River for six months. They must submit a report on the progress of the agreement every two months, and in case of breach, they will be imprisoned and fined.

It is the first time that a restaurative agreement has been reached for the crime of ecocide. “We have understood that by depriving a person of liberty many times we do not succeed in reintegrating them into society, what we want is to re-socialize people who commit a crime. Let us not forget that at the end of the day, with the current criminal system, we are privileging restorative justice where it not only serves to punish people who commit a crime but can also benefit society,” said Jorge Luis Llaven Abarca, attorney general of the state of Chiapas. In Chiapas, 23,000 hectares of protected natural reserves have been recovered that could be reforested through restorative justice agreements.

Government reforestation programs: limitations

During the previous six years, several million-dollar reforestation programs were launched without success at stopping the rapid deforestation. On the contrary, they were denounced for mismanagement, irregularities, and financial anomalies. Felipe Calderon (2006-2012) started, for example, the ProArbol program in 2007, which was intended to collaborate with the United Nations Environment Program’s plan to plant one billion trees. Two years later, an investigation conducted by Greenpeace Mexico revealed that only 10% of the sown species had survived, due to being planted in inappropriate areas for growth. More than half of what was planted was not trees, but cacti. According to Greenpeace calculations, 2,430 million pesos were lost during the first two years of the program. The program was not canceled, rather Calderon ordered it to be improved, however losses and mismanagement continued. Before the avalanche of criticism, the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR in its Spanish acronym) ended up admitting that ProArbol planted fewer trees than agreed and that it was a “virtual” reforestation. Its director, Jose Cibrian Tova, resigned without receiving any sanctions.

During the six-year term of office of Enrique Peña Nieto (2006-2012), almost two billion pesos went towards reforestation. For the most part they went to the pockets of agroindustrial investors, sellers of agrochemicals, or corporations that hold global ownership of seeds. The subsidies that reached the people were used in a clientelist and partisan way, and with a welfare approach aimed at maintaining poverty at tolerable limits. This goal was certainly not achieved, said Raul Benet, independent adviser on environment and territory and Biologist for the UNAM Faculty of Sciences. He considers that the result of these assistance programs has been the general abandonment of the countryside, the strengthening of a subsistence economy based on subsidies, and a pressing and growing poverty. These programs have directly caused the loss of millions of hectares of forests and jungles, the contamination of soils and aquifers, the serious deterioration of ecosystems and the consequent loss of biodiversity, he says. They have also contributed significantly to the emission of greenhouse gases that cause climate change.

Greenpeace also explains that reforestation and commercial plantations do not necessarily help to stop deforestation, since it is barely possible to recover a third of the forest area that is lost and, of the trees planted, a minimum part, less than half, survive

The new Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life) program

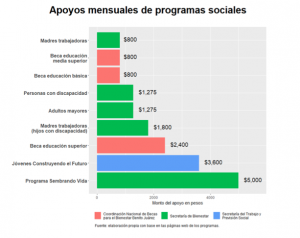

The Sembrando Vida program presented by the government of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador aims to break drastically with the previous programs. The stated objectives imply “contributing to the social well-being of agrarian subjects in their rural locations and promoting their effective participation in integral rural development, productive restoration of the countryside, cultivating corn, cocoa, vegetables, and fruit trees in one million hectares of 19 states in the country.” The possible beneficiaries have to be owners or holders of 2.5 hectares available for the program, receiving a support of 5,000 pesos per month, of which 500 will go to a savings bank. The project has started in the states of Veracruz, Tabasco, Chiapas, and Campeche with inconclusive results.

Both Subcommander Galeano of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN in its Spanish acronym) and the Mexican Network of Forest Peasant Organizations (Red Mocaf) agree in their rejection of the program for its various negative impacts. “The delivery of support to ejidatarios individually can generate division, destroy the social fabric and aggravate the situation of violence and insecurity against community leaders, defenders of the land and the environment,” said Gustavo Sanchez, director of the Mocaf Network. He uncovered historical problems in land tenure in the country, in addition to generating family disputes over who is the “legal” owner of land.

No to the Sembrando Vida project, one of the claims of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) in San Cristóbal de Las Casas in June 2019 © SIPAZ

Paradoxically, the program has caused more intentional and illegal logging. “If a farmer has two and a half hectares, but only one is deforested, what he does is cut the other hectare and a half so that they complete the quota requested by the government,” said Rene Gomez, president of the organization Bosques y Gobernanza (Forests and Governance), in Ocosingo, Chiapas. The technicians and authorities responsible for Sembrando Vida are instructed not to include plots that have been established by destroying jungle or forest in the program, but at least in some cases they were included in the program since the program lacks a monitoring system.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the trees that are sown today through Sembrando Vida are not intended to be kept untouched, but can be cut as soon as they reach the size indicated for sale. The Otros Mundos organization in Chiapas denounced that, “these programs, created from an outside view of the forest and the countryside, do not adapt to the reality of the people or even seek their welfare. Rather, they are programs that seek to maintain an extractive system, so that the production of goods and the accumulation of capital by a few corporate networks can continue to be justified at all costs. At the same time, these programs leave the campesinos and native peoples in a situation of wage slavery on their own lands, chained through contracts and criminalized when they decide to treat the land as their grandparents and grandmothers used to do, and regain control over it.”

Looking Ahead…

The policies and programs that have been implemented as a respond to the situation of forest resource management have been insufficient. Experts in the field consider that forestry policy requires progress in the clear definition of property rights, respecting the conditions of community property; identification and promotion of successful community forest management schemes and models; resources to increase technical capabilities and strengthen the social capital of producers; strengthen market and financing schemes to promote community development; and design a regulatory framework of incentives for producers to make a comprehensive and diversified management of their natural resources in favor of sustainable development and conservation.

“It is necessary to redirect efforts to a policy focused on the integral development of forest regions, to put aside the welfare approach focused on the distribution of subsidies,” the Mexican Civil Council for Sustainable Forestry states.