FOCUS: Between deforestation and poor reforestation – Mexico, a country of authorized ecological destruction

27/09/2019

SIPAZ Activities (from mid-May to mid-August 2019)

27/09/2019Clearly the need is so great that it is up to the State to ensure that families have their homes, so that they can recover their wealth.

The night of September 7, 2017 represents a traumatic moment in the lives of tens of thousands of people, when a magnitude 8.2 earthquake shook the coastal areas of Chiapas and Oaxaca, leaving 102 people dead, thousands homeless, and the region in chaos.

In the midst of this horror and anguish, however, something emerged that in the next two years became the driving force behind the long but dignified process of reconstruction: community solidarity.

The night’s impacts are still visible and, in many places, palpable. While the most obvious signs of destruction have been removed, for a complete rebuild many materials and resources are still lacking, as well as coordination.

A Civilian Observation Mission that took place in Oaxaca a few days after the earthquake highlighted that “the urgent, basic needs of the people affected by the earthquake have not been met.” In addition, the mission criticized a “lack of government coordination regarding the distribution of humanitarian aid and the discretionary use of scarce resources that have arrived in the area.” This pattern was reiterated repeatedly during the process of care for the victims, who are in various stages of the rebuilding process.

These inequalities originate from mistakes made from the beginning of the response. There were failures not only in the distribution of humanitarian aid, but also in the census of victims and the allocation of funds. Various civil and social organizations reported that some families with damaged assets were not included in the census and therefore were not taken into account regarding the reconstruction funds. In other cases, damaged assets were incorrectly counted, unfairly limiting support to these families. Other families simply did not receive the promised monetary aid, while unaffected people received money from these funds. In this context, in June of 2018, the All Rights for All Network “detected that in the face of irregularities reported by victims, federal and state authorities have not properly coordinated nor assumed their responsibilities.”

All of these circumstances created a situation in which families whose property was damaged were forced into debt or sold valuables to continue rebuilding, or had to live in unsafe homes after the earthquake.

In the absence of an adequate response from the authorities, civil processes were formed to deal with the crisis and promote community reconstruction. In the days following the earthquake, community reconstruction included the collective rescue of trapped people, distribution of basic necessities, and the accommodation of affected people in places of refuge. After the initial response, unity and reciprocal support became a continuous process for some communities.

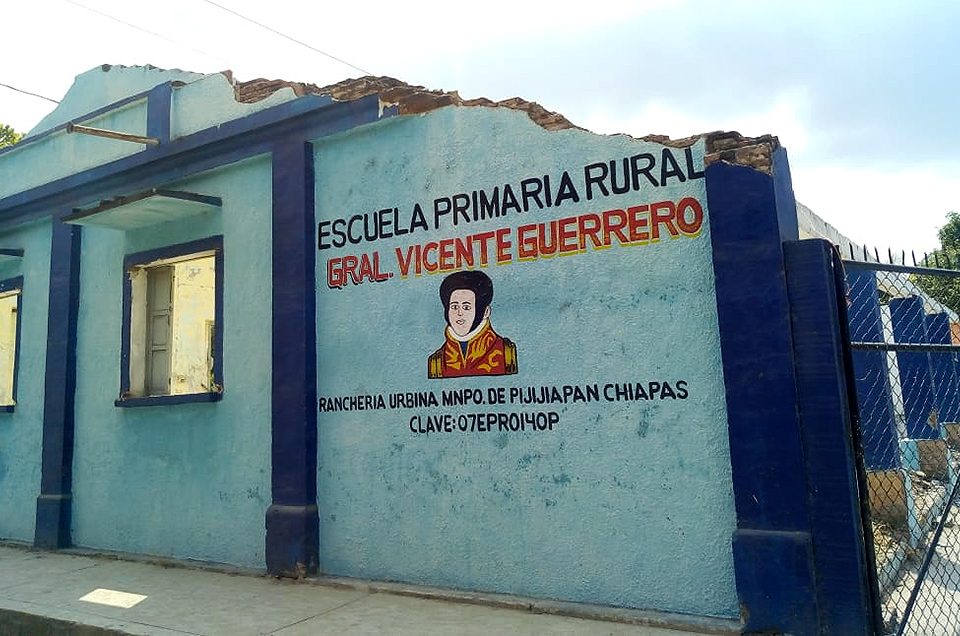

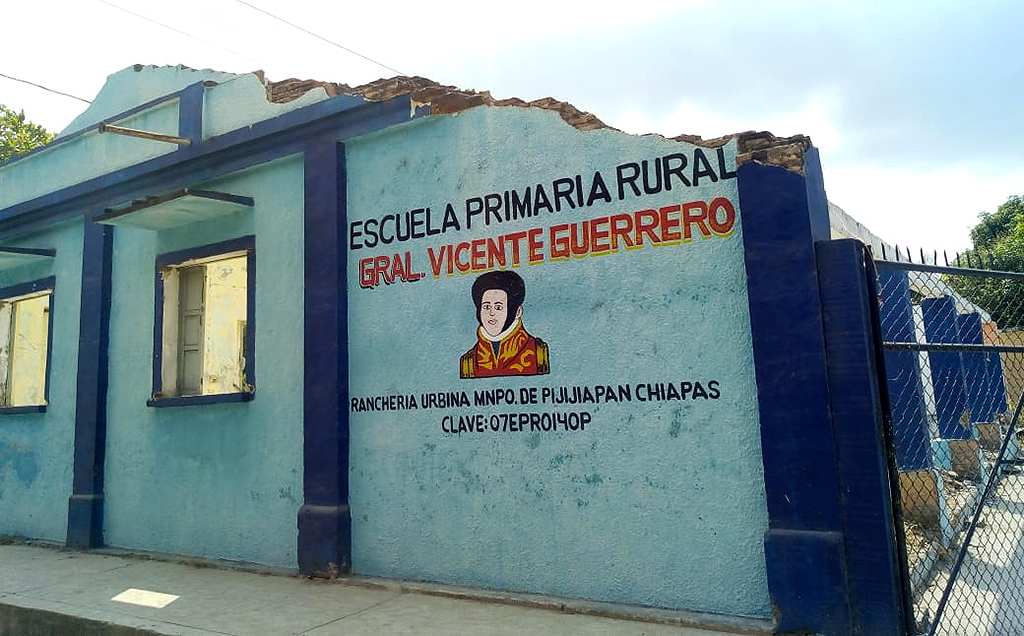

One example of this is the reconstruction process organized by the Digna Ochoa Human Rights Center in the municipalities of Arriaga, Tonalá, and Pijijiapan in Chiapas. Like many organizations and individuals, they reacted in light of the crisis by organizing the delivery of humanitarian aid and coordinating medical and psychosocial care brigades.

“We also promoted cultural activities and recreation, as a way to get to the themes of stress and fear, with the help of medical attention brigades. Combining all the activities and actions focused on improving the situation inside (of survivors), because in this moment there was not only fear. There was terror, tension; there were economic complications. There was not enough food, because there was no work, etcetera. Several things happened,” explained Nathaniel Hernandez, director of Digna Ochoa, in an interview with SIPAZ.

As the beginning of the rebuilding process, Digna Ochoa toured the affected communities to conduct their own census as well as an evaluation of the damages. “Once we knew the magnitude of the material damage, we could determine what the approach was going to be to start material reconstruction, as well as social. An essential part of the project is the participation of the community which, in part, is ensured by a reconstruction committee made up of villagers. It is a measure to “know firsthand the needs of each family in the communities and to establish a more intensive channel of communication.” Another element is complete transparency about all the funds in the accounts of the Human Rights Center and the specific costs for the reconstruction of houses. Finally, the proposal was that the families in the communities, where resources were going to be allocated, would support and collaborate in the process of physical work. This led to the recovery of approximately 150 homes with 38 more that have yet to be completed.

In March of this year, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) announced that reconstruction from the earthquake will begin, with a budget of 10 billion pesos for 2019, of which 2.7 billion pesos will be allocated in a first stage in Chiapas and 4.7 billion pesos in Oaxaca. Although civil organizations observe new movement, the proposal maintains the main error of the previous government- using the same census and thus excluding those who were not counted the first time “and they continue waiting for the response of the current government to access public funds.” The influence of non-governmental organizations in these cases is limited, because “it is an issue in which there are no longer funds available.” In order not to leave the affected families without any form of support, Digna Ochoa continues to share information about the reconstruction plan with them as well as “sharing with the authorities the censuses we have taken, so that they can be considered”.

Taking into account the context of serious mistakes made by the authorities, and the affected population being forced to “accept aid that did not fit their reality” while suffering ongoing trauma from the earthquake, community reconstruction is more than an alternative route. It is a course of action which respects the victims and their needs. It is a way of using and reinforcing existing social cohesion. Above all, it is a ray of hope in a process that often seems endless in its injustice.