SIPAZ Activities (Mid-February to Mid-May 2020)

03/06/2020

FOCUS: Who are the beneficiaries of the USMCA?

04/09/2020In recent weeks, Mexico became one of the countries with the most cases of COVID-19 worldwide with at least more than half a million cases of contagion (sixth place) and, by mid-August, one of those with the highest mortality rates (third place), with more than 50 thousand dead.

With more than 60% of the economically active population in the informal sector and in need of going to work despite the risks, the government has opted for a model that calls for social distance but not in a mandatory way. The country, in addition, has had to face the pandemic with a health sector that was robbed by previous administrations, and with a high percentage of its vulnerable population, whether due to obesity, diabetes, or hypertension.

Many voices have criticized the government response, its results and the fact that the situation is probably worse than official figures, as Mexico is among the lowest test rates among the major economies. From the beginning, Mexico opted for the model known as Sentinel, established in 2006 for diseases similar to seasonal influenza, through a network of 475 monitoring stations. The model, Hugo Lopez-Gatell, Undersecretary of Health and spokesman for the government health strategy, explained at the time allowed Mexico to make projections with partial data as in an “opinion poll.” Although from the beginning of June, it passed on to what has been called the “new normal”, two and a half months later, more than half of the states were still at a high or maximum risk level.

New free trade agreements: a chance to curb the economic impacts of the pandemic?

On July 1st, a new agreement between Mexico, the United States, and Canada called USMCA, came into force, which constitutes an update of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which had been in place since 1994 (see Focus). In this framework, and on his first international trip, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) travelled to Washington to meet with his counterpart, Donald Trump. Some analysts underlined the importance of this visit, when due to the pandemic, the reactivation of the Mexican economy will depend largely on the United States, this country being its largest trading partner, and, due to the sending of remittances from the more than 12 million Mexicans In the United States, it represents the largest financing of foreign money (more than direct foreign investment or foreign exchange left by tourism and just below oil revenues). However, this meeting has been criticized by other specialists given the fall in the electoral preferences of Donald Trump, and because the current US president, on more than one occasion and since his campaign in the previous election, has expressed himself in a contemptuous and racist way towards Mexicans. The USMCA raises a series of concerns, seeing the balance at least mitigated from what was NAFTA and on different issues, in particular freedom of expression with new digital laws and for Mexican territory.

Previously, another free trade agreement was also approved, the “Economic Association, Political Concertation and Cooperation Agreement”, between the European Union and Mexico. In July, there was a meeting at the IX° edition of the High-Level Bilateral Dialogue on Human Rights, where challenges and experiences were addressed, in particular “to prevent the global health crisis from exacerbating existing problems.” Within this framework, more than one hundred Mexican organizations and international networks prepared a report on the situation of human rights in the country. They warned about the fact that the crisis itself is “exacerbated by the effects of the health and economic crisis that have had a disproportionate impact on the human rights of the victims.”

Although the organizations valued that the AMLO government has “recognized, in part, the magnitude of the human rights crisis,” they considered that “in practice, high rates of violence and human rights violations and impunity continue to be maintained.” The diagnosis covers a wide range of issues: the disappearance crisis; the vulnerability of human rights defenders and journalists; violence against women, children, migrants, indigenous peoples and the LGBTTTI + community; the structural deficiencies of the justice administration institutions; the continuation of the militarization of public security, and the failure to comply with international recommendations. Regarding the “Association Agreement”, they highlighted the closing of the negotiations during the pandemic, “without consultation or participation of civil society, which shows the prioritization of economic actors over human rights.”

A health crisis that exacerbates existing problems

In May, AMLO once again denied that gender-based violence was on the rise, and ruled out that there was any relationship with the lockdown. Several civil organizations regretted the president’s statements, among them, the National Shelter Network (RNR) stated: “It is very serious that these statements are made, wherever they come from, in a country where there are ten femicides a day on average, but if they also come from those who have the responsibility of guaranteeing the life and safety of women and children, it is a message that perpetuates impunity and the naturalization of violence.”

In June, the agreement that will allow the creation of an Amnesty Commission was officially published. The amnesty law was urgently approved two months earlier, mainly under the argument of depressurizing mostly overcrowded prisons and preventing COVID-19 infections. It will exclusively benefit people in prison for minor crimes of the federal jurisdiction. Bureaucratic problems due to the austerity measures announced by the government of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, delayed the installation of this commission. In the meantime, it became clear that this law will not be of much help in the face of the risks of the pandemic in the prison system, both due to the time it takes and its limited scope. However, it could be relevant to what analysts consider “the excessive use we are making of criminal law and the prison system.”

In July, the Undersecretary for Human Rights, Population and Migration released a report documenting human rights violations during the emergency. Since March 15th, 140 attacks against journalists and defenders have been registered. Chiapas and Oaxaca were the states with the highest rate of violence. Activists who defend the right to health protection suffered 103 attacks in 29 Mexican states.

In August, the Network for the Rights of the Child in Mexico (REDIM), presented an analysis of the impact that the pandemic has had on children. It pointed out that there was already a human rights crisis before the spread of the virus, with 49% of children living in poverty, which will worsen with the economic crisis. “It is estimated that before COVID-19, 3.2 million girls, boys and adolescents between the ages of 5 and 17 were in a condition of child labour,” said REDIM, which estimates that this figure could increase to 4.5 or 5 millions. Another worrying aspect is the right to education: The “distance learning” model that is proposed for the new school year will not work for everyone due to the lack of a computer or internet. Before the pandemic, some 4.8 million girls, boys and adolescents were out of school. Due to confinement, boys and girls are even more exposed to domestic violence. “A new agenda of actions is required that must be discussed, to face the effects of the pandemic,” said the System for the Protection of Girls, Boys and Adolescents (SIPPINA).

Megaprojects: another point of tension with civil and social organizations

In June, AMLO started his tour to inaugurate work of the Maya Train. 244 organizations stated that this is unconstitutional, since there is a history of multiple calls from social players to interrupt non-essential activities during the pandemic, as well as the injunctions granted by federal judges for the suspension of the project. Lopez Obrador’s visit “disregards and ignores court orders affecting the delicate balance and equilibrium of the exercise of power in the country,” they affirmed in a document. They also stated that, in the advance of the project, “the rights and guarantees of the population have been trampled upon and the rule of law has been violated,” and that the legal processes initiated against the megaproject, “have evidenced clear violations of the law, contradictions and falsehoods.”

In August, members of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Metropolitan Anticapitalist and Antipatriarchal Coordination, reported on two legal appeals that they presented against five megaprojects of the Mexican government. They filed an indirect injunction and a complaint before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR). “The laws that exist are prescribed by companies that approach the legislators so that the dispossession becomes legal. The laws are not a great hope for us, but now we are turning to both national and international courts to make sure that we want to fight”, said Pedro Regalado Uc, defender of Maya territory. The projects in question are the so-called Maya Train, the Trans-isthmic Corridor, the International Airport in Santa Lucia, the Dos Bocas refinery (Tabasco) and the Morelos Comprehensive Project. They denounced that a consultation was not carried out in accordance with international standards and criticized the damage to the cultural and archaeological heritage that they will cause.

CHIAPAS: Covid-19, “The figures that don’t add up”

Since the beginning of the pandemic and to date, representatives of the National Union of Workers of the Secretariat of Health of the State of Chiapas, have warned about the precariousness in hospitals in the state, as well as the lack of medicines and supplies. In addition to the risk of contagion, there have been various attacks against medical personnel and hospitals in different parts of the state, in most cases after false information that has circulated on social networks and in particular against sanitation and fumigations.

For several weeks, the figures presented by the Ministry of Health, would imply that the most critical point of the pandemic has already been exceeded and has gone hand in hand with an increase in mobility and normalization of activities. However, several media have questioned the veracity of these figures, which do not even coincide with those handled at the federal level. “The reality that the population manifests is different, hundreds of people report the contagion and death of their relatives, in their homes, without medical attention, without having been tested”, Chiapas Paralelo reported.

Another situation that has generated mobilization inside and outside Chiapas has been the arrest in July of Dr. Gerardo Vicente Grajales Yuca. In previous days, the doctor had treated several patients infected with coronavirus, including former local deputy Miguel Arturo Ramirez Lopez, who unfortunately died. The daughter of the former official, denounced that Grajales Yuca asked her for material and supplies to care for her father, for which she filed a complaint for “abuse of power.” Protesters who sympathized in his case, said that Grajales Yuca only did what has become “normalized” since the beginning of the pandemic, to ask the relatives of patients for supplies that hospitals do not have. Although Grajales Yuca has been at home due to a health problem since August, he continues to face an “unfair criminal process, which laid bare the privileges of a political class that was supposed to no longer exist in Chiapas,” the Federation of Medical Associations of Chiapas denounced.

Human Rights: Unresolved issues

Since May, the Trust for the Health of Indigenous Children in Mexico (FISANIM) and the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba), warned about the risk of hunger for more than 3,000 displaced people in the Highlands of Chiapas. They are not the only people faced with a situation of this type, as there are also cases in several municipalities representing a total of 10,113 victims of forced displacement in the state.

One of the most violent situations is occurring between Aldama and Santa Martha (municipality of Chenalho), due to a long-standing 59-hectare territorial conflict that has caused at least 25 deaths, dozens of displaced persons and several injuries. According to Frayba, from March 2018 to date, 307 armed attacks have been registered. In the same period, it made “167 interventions with various bodies of the state and national governments, without having an effective response.” On July 30th, the municipal authorities of Aldama and Chenalho ratified the non-aggression pact signed the previous year to prevent further violence.

OAXACA: Cases and forms of aggression against defenders increase

In May, the environmental defender Eugui Roy Martinez Perez was assassinated in an armed attack in San Agustin Loxicha.

In June, outside the doors of the Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity Oaxaca, a black bag with pieces of meat and a written death threat was found. The feminist organization denounced that the threat could be related to the questions that have been raised with the government of Alejandro Murat over femicides, disappearances of women and attacks on defenders.

In July, the Coordination for the Freedom of Criminalized Defenders in Oaxaca expressed its concern over the detention and torture of the defender Joaquin Zarate Bernal, a member of the Democratic Civic Union of Neighbourhoods and Communities (UCIDEBACC). The arrest warrant against him derives from the same criminal case that held two other members of UCIDEBACC in prison for almost six years, which led to a statement from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

This same month, the Coordination also denounced the death of human rights defender Nicasio Zaragosa Quintana, a member of the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Isthmus Region (UCIRI), in the Santo Domingo Tehuantepec prison. It held the state authorities responsible for the death due to “the conditions in which hundreds of inmates live in Oaxaca, who do not have the right to health and food guaranteed, they live in conditions of overcrowding and subhuman isolation.” According to the Coordination, his political participation in the UCIRI is what led him to jail where he had been held since 2003 in a criminal process that was about to be reinstated for procedural violations.

Another issue of concern: gender violence. In June, Consorcio Oaxaca reported that, faced with confinement, “hundreds of girls and women find themselves in contexts that were already dangerous due to the high rates of aggression to which they are exposed on a daily and systematic basis.” It explained that from March 21st to date, 16 femicides have occurred in Oaxaca. From December 1st, 2016 to date, there have been 427 femicides in the entity. This, “without the State showing willingness to guarantee the security and access to justice for the victims and their families.” It stressed that family violence increased 25% compared to last year. Seven cases of sexual crimes were also registered so far in the contingency.

The question of land and territory remains at the center of many social claims. In June, a few days after AMLO’s arrival to inaugurate to the Trans-isthmic Corridor, more than 100 civil organizations, academics and artists declared their opposition to the project, considering that “it is violating the right to self-determination of indigenous peoples.” When the consultation carried out in March did not comply with international standards on the matter they denounced. They claimed that “there are injunctions brought by Mixes, Zapotecs and Ikoots of the Isthmus against the interoceanic corridor project, and therefore, the legal conditions do not exist.” They also recalled that “the alleged Environmental Impact Statement was not authorized because it was plagued with irregularities and serious omissions.” They pointed out that AMLO “is taking advantage of the lockdown due to the pandemic, which limits our most elementary rights, such as the right to assembly, protest and mobilization to impose (…) his own concept of essential projects for the Nation.” Despite the criticism, AMLO did the launch, explaining that “the intention is to contain migration in these communities so that people do not abandon them in search of work in the north.”

In July, the Oaxacan Assembly in Defense of the Land and Territory published a statement in the framework of an AMLO tour in the state in which it denounced that “the works of the train are starting, violating the rights of indigenous peoples, of the earth and nature with simulated and rigged consultations.” “The development announced by the government is not the today or the tomorrow that we want (…) The community, the collective, mutual support, the communal work, traditional community labor, real solidarity, are the ways that will move us forward”, it said.

Regarding impunity, it is worth highlighting a possible advance in the midst of a multitude of cases that have failed to break with this trend. In June, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) determined to hear the appeals for review presented by the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA) and the Attorney General’s Office (FGR) before the injunction trial for forced disappearance of the members of the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR), Edmundo Reyes Amaya and Gabriel Alberto Cruz Sanchez. These disappearances occurred in 2007 in the City of Oaxaca, presumably at the hands of the Army and the then Ministerial Police of Oaxaca. In August, arrest warrants were issued for the former head of the State Investigation Agency (AEI), the former head of the then State Attorney General’s Office (PGJE), and other commanders of that body, for their probable responsibility in this case.

GUERRERO: Ayotzinapa, cracks in the impunity pacts?

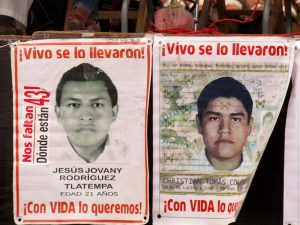

Several advances were presented in the Ayotzinapa case during the period. In June, the arrest of Jose Angel Casarrubias, alias “el Mochomo”, leader of Guerreros Unidos, a criminal group identified in the disappearance of the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Normal Rural School in Iguala in September 2014, generated expectations. Although a federal judge ordered his release based on a technicality about the evidence presented by the then Attorney General’s Office (PGR), he was arrested immediately afterward. In addition, an arrest warrant was issued against Tomas Zeron, former director of the Investigation Agency of the PGR, who fled the country. Finally, 46 arrest warrants were presented against Guerrero officials who were possibly involved.

In July, the Special Unit for the case announced that they had identified the student teacher Christian Alfonso Rodriguez Telumbre, one of the 43 disappeared. “More than five years after the events, human remains belonging to one of the victims have been identified. This, moreover, was not dumped or found in the Cocula Tip, nor in the San Juan River, according to the version that, publicly and judicially, the previous administration upheld… (…). Today we tell families and society that the right to the truth will prevail, the search for their children will continue and we will guarantee the right to justice”, said the Head of the Unit for the case. The Agustin Pro Juarez Center declared that “the pacts of impunity and silence that surround the Ayotzinapa case are beginning to break down, but we still cannot consider them broken. The next few months will be key to knowing if, with new accusations and new searches, it is possible to get to the truth.”

New cases of concern continue to arise. In June, human rights defender Kenia Ines Hernandez Montalban, also a member of the Colectivo Zapata Vive, in the state of Mexico, was arrested. Hernandez Montalban is a beneficiary of the Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. She was arrested for her alleged participation in the crime of robbery with violence. After five days in jail, Hernandez Montalban was released with conditions. Several civil organizations expressed concern about the criminalization of defenders and demanded the unconditional release of the defender.

Also, in June, the journalist and defender, Hercilia Castro Balderas received death threats from two men who came to her home in Zihuatanejo, where she was with her partner, also a defender of the territory. The CCTI reports that the defender “has been repeatedly threatened in the last month for her defense work and denouncing acts of the municipal government of Zihuatanejo and the National Guard. Two weeks ago, her house was searched and there were physical attacks.”

In July, the CNI published a statement from the Indigenous and Popular Council of Guerrero – Emiliano Zapata (CIPOG-EZ), in which it denounced the injustices and armed attacks, even deaths, that it faces. Despite the government’s promises to provide security, “gunfire once again shook the lands of Chilapa in the hands of the narco-paramilitary group “Los Ardillos.”” They reported that on July 11th, 100 members of that armed group opened fire on the Tula community. They highlighted that “the events occurred barely two kilometers from the permanent base of the National Guard, who listened to the more than three hours of shooting, doing absolutely nothing.”

In August, journalist Pablo Morrugares Parraguirre was murdered in Iguala. The director of the digital newspaper PM Noticias de Guerrero, had been a beneficiary of precautionary measures from the Mechanism for the Protection of Journalists and Human Rights Defenders since 2015. Also, in August, the facilities of Diario de Iguala were shot at by unknown assailants. Article 19 and the Montaña Tlachinollan Human Rights Center recalled that there is a dispute between organized crime groups for control of that area, who threaten journalists to say or stop saying things according to their interests.

Impunity remains intact in many other cases. In June, Tlachinollan recalled the massacre committed by the Mexican army in the community of El Charco, in the municipality of Ayutla de los Libres in 1998. Soldiers arrived at the place on June 7th, 1998, leaving 11 extrajudicially executed, 27 tortured and arbitrarily detained and five injured. Tlachinollan denounced that “an investigation was never opened against the military who killed the campesinos” but there was of 27 indigenous people who were charged with various offenses, were prosecuted and spent more than two years in prison. “It is an example of what happens when the Mexican army performs public security tasks, lacks civil controls and accountability mechanisms”, it said.