2005

02/01/2006

ANALYSIS: Mexico-Chiapas, On the Road to the Elections

28/04/2006Within a context of Latin American governments swinging further and further to the left (Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, and most recently, Chile), Mexico is approaching its own presidential elections on July 2nd. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, representing the Alliance For the Good of All (left) made up of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), the Worker’s Party (PT) and the Convergence, is a candidate strengthened by his popularity that guarantees him a broad social base. Felipe Calderón Hinojosa was named as the candidate for the National Action Party (PAN). This is the party that is currently in power, which is considered to be a disadvantage as seen by the vote of punishment carried out by members of the PAN during the internal party elections: Santiago Creel, considered the candidate preferred by President Vicente Fox, lost. In the Party of the Institutional Revolution (PRI), following the questioning of his and his family’s holdings, Arturo Montiel resigned from his candidacy, opening the space for Roberto Madrazo. In the internal elections on November 13, Madrazo received a resounding triumph over the little-known Priista, Everardo Moreno. As in 2000, the PRI renewed its alliance with the Ecological Green Party of Mexico (PVEM).

While the polls show a slight advantage for López Obrador, the elections held since 2000 have favored the PRI, maintaining its position as the premier political force in Mexico at the municipal, state, and Congressional level. With three strong candidates, shown by the polls to have comparable support, and a large sector of the population still undecided (calculated to be up to 40%), there is concern about the temptation to generate a “vote of fear,” which is to say inhibiting people associated with a certain party from voting, to insure the victory of a different party. The increased weakening and discrediting of the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) presents the risk that the IFE will not be able to serve its function as arbitrator, increasing the doubts and concerns about the electoral process.

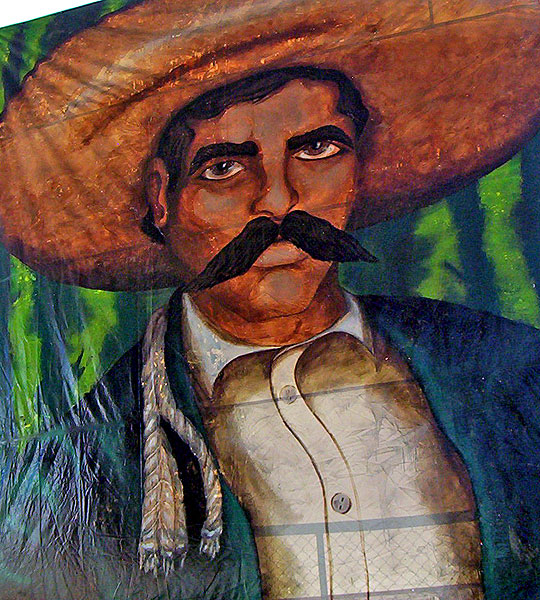

With the electoral campaigns underway and a large sector of the population following the intense interparty disputes, the Zapatista Army for National Liberation (EZLN) is not proposing the possibility of returning to negotiations with the next government. Rather the EZLN has opted for the opening of a new phase in the dialogue and the construction of non-electoral alternatives with civil society. This proposal was born from the Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona (June 2005) and is called the “Other Campaign,” a clear reference to the electoral context. Growing out of the crisis in representative democracy, and unattached to the results of the upcoming elections, the Other Campaign is positioned “below and to the left,” aiming to build a plan for national, anticapitalist struggle. As was already stated in the Zapatista communiqué “The Rebellion and the Chairs” (October 2002), for the EZLN it is not so relevant to see who gets to sit in the chair (in this case the President’s seat), but rather to question the very concept of the chair, of power.

The “Other Campaign” Takes Off

Following a first series of meetings, in August and September, with various actors in a number of Zapatista communities in the Selva Lacandona, and as announced in the Plenary Session in mid-September, a new phase began in January. This new strategy aims to analyze not only the current situation in the different states of Mexico, but also the various ways the population is responding to those circumstances. The task of touring the nation has been assigned to Subcomandante Marcos, now renamed Subdelegate Zero: “It falls to me to go on tour first to see what the road we will take is like, to see if there are any hazards, and to get to know the faces and the words of the compañeros and compañeras who are different from us.”

This effort started in San Cristóbal de Las Casas on January 1st. A number of commanders and thousands of people from the support bases of the EZLN arrived to send off the Subdelegate. At this event, the Comandante David recalled: “On the twelfth birthday of the armed uprising, against exclusion, against degradation, and against all sorts of injustices that we suffer as indigenous peoples and peoples of Mexico, we say that we are here, and we will be here and everywhere, and this is why we have joined together once again in this city of San Cristóbal…, but today thousands of people from the support bases are here… to give a formal beginning to the next step that we, the EZLN, have chosen with the hundreds of thousands of compañeros and compañeras of Mexico and of the world, who have embraced the Sixth Declaration and the ‘Other Campaign’ to open paths, to open doors, and touch the hearts of other indigenous and non-indigenous brothers, poor like us, and all of those who want a real change in our country and who want a true society where we can live in real democracy, with liberty and justice for all…”

As the final speaker, Subcomandante Marcos expressed: “If something happens to me, I want you all to know that it has been an honor to struggle alongside all of you, you have been the best teachers and leaders and I am certain that you will continue to take our struggle in the right direction, showing everyone how to be better with the words of dignity. We are the wind, we are not afraid to die in the struggle. The good word has been planted in the good earth, and this good earth is the heart of all of you and in it blossoms the Zapatista dignity.”

The tour that will cover all the states of Mexico between January and June, started in Chiapas. On January 6th, Comandanta Ramona, a founder of the EZLN, died. The tour was interrupted in Tonalá (it returned three days later), extending the Chiapas portion until January 14th. Rallies and meetings were organized throughout the state: San Cristóbal, Palenque, Chiapa de Corzo, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Tonalá, Pijijiapan, Huixtla, and Trinitaria. While the number of participants and the content of each event varied, one thing remained constant: the high level of social discontent. The presence of Subcomandante Marcos and the primarily alternative press served as a sounding board for all types of complaints, ranging from sewage problems, the high cost of electricity, the lack of relief for the area affected by the hurricanes, etc. The Subdelegate Zero sums it up in this statement: “the problem of Chiapas is the same that exists in all the states of Mexico: the system of capitalism.” In a number of places, Marcos had the chance to clarify his role within the EZLN, given the cult that has grown around his character, the role of the EZLN within the Other Campaign, as well as what the Other Campaign is, and especially what it is not. Many people approached him hoping he would resolve their most pressing issues as if he were “another candidate” for an elected position, which he has firmly denied.

In each place, the Subcomandante questioned the presidential candidates and the political parties, placing particular emphasis on the non-electoral character of the Other Campaign. For example, in Palenque on January 3rd: “everyday that they come we will hear a ton of promises, lies, trying to feed our hopes that things will get better now if we trade one government for another; time and time again, every year, every three years, every six years, they sell us that lie and once every three years, every six years, they repeat it again. We, the compañeros of the Other Campaign, of the EZLN, think that they will not give us anything. Nothing that we do not achieve from our own efforts, with our organized effort to transform things. The governments that we have, in addition to lying to us, in addition to depriving us of the little that we have, they charge us high prices for the things we buy, and for the things we produce, as campesinos and as workers, they pay us a miserable wage. (…) We believe that all this must change and it will not change from above, where the right is passing out lies in every direction, while pocketing millions and millions of pesos. We believe that change can only come from below or from the left, and that is why we invite all of you who consider yourselves humble and simple people, if you want to change things, if you want to make for yourself, for your children, for your grandchildren a world where we can live without fear. Without fear of being degraded or belittled for the color of your skin, for your way of walking, for your way of talking, for your culture, or for the position you have within this society.” In Chiapa de Corzo on January 5th, he stressed: “Do what your heart tells you, but make your heart think and give it words of dignity. Respect yourselves, and demand that those who speak to you respect you and consider you. In the campaigns you are only significant because you have a voter’s card. The Other Campaign is precisely something else.”

A fundamental element and goal of the Other Campaign is to organize and coordinate processes of struggle and resistance. In Pijijiapan, Marcos called for a “great statewide mobilization and later a national mobilization” against the climbing rates of electricity, affirming “Do like us, but without the arms! – Unite all your small struggles and make a single, but massive, one that the government cannot defeat.”

The reactions of the political actors oscillates between silence (creating an empty space around the proposal), a celebration of the political, civil and peaceful nature of the Other Campaign (by the spokesperson of the Presidency), and direct criticism affirming that the Subcomandante Marcos has lost his presence and his followers, questioning the sources of funding for the EZLN and the Other Campaign and its lack of substance, among other issues. After Chiapas, the Subdelegate Zero continued with his tour heading to Quintana Roo and Yucatán…

Chiapas in the Context of the Elections and the Other Campaign

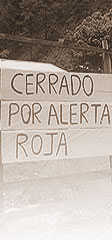

First, we must note that nearly half of Chiapas remains in an extremely vulnerable situation because of the effects of Hurricane Stan (October 5th) and to a lesser degree, Hurricane Wilma (October 21st), in the southern part of Mexico. Stan ravaged millions of acres in Veracruz, Hidalgo, Puebla, Oaxaca and Chiapas, where the greatest damage was reported in rural areas and the poorest parts of towns and cities, because of their position in zones of great risk. There are thousands of affected homes, communities cut off from communication, destroyed highways, and hundreds of collapsed bridges. The figures vary but it is calculated that between twenty and one hundred people died.

In November a report was issued by a number of civil organizations that form a part of the Network of Organizations for the Emergency in Chiapas which stated, “we have established that the official versions are false. The humanitarian assistance to the rural populations of the Coast, Sierra, and Soconusco regions has been minimal and disorganized. The dirt roads, local roads, bridges and hanging bridges, essentially have not been repaired at all, with the exception of the few highways that connect to the rest of the state. Hundreds of rural communities in many municipalities of the Sierra remain incommunicado with no attention to their basic health, education, and nutritional needs. Meanwhile, the major part of their crops have been destroyed or they lost completely their only harvest of the year.”

Hurricane Wilma primarily affected the hub of tourism along the Mayan Riviera and Cancun, generating a much more immediate economic response, because of the interests at stake. The south of Mexico did not receive the same attention. The reconstruction will take much longer, with the risk of an increase to the already growing migration, of Mexicans as well as Central Americans, since the whole region was affected by the two hurricanes. Also of concern are the potential and actual efforts on the part of politicians to capitalize on the disaster. In more than one space, including the tour of the Subdelegate, there have been reports of humanitarian aid being blocked so that the supplies could be used for proselitizing.

In the past months there has been a highly volatile social context in the area of Zapatista influence. This could cause some conflicts to move towards a situation of generalized violence. There are two primary “hot spots”: the area of Chilón and the area of Las Margaritas. In mid October, it was reported that members of the Organization for Indigenous and Campesino Defense (OPDDIC) were planning to dismantle the autonomous municipality of Olga Isabel and detain the community’s leaders. The Zapatista Good Government Council of Morelia also reported the presence of 35 people with firearms. In November, in Las Margaritas, the organization the Independent Center of Agricultural Workers and Campesinos (CIOAC) attributed the death of six of its members to the Zapatistas. The EZLN subsequently cut off its ties to the group. In December the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center reported that “there is a latent risk of new acts of violence (…) in the municipality of Las Margaritas, in the named conflict zone” if the situation is not adequately addressed.

Human Rights: “A Long List of Unfulfilled Promises”

On December 10th, in the context of the 57th anniversary of the enactment of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, activists and defenders of human rights affirmed that “a long list of unfulfilled promises” exists in Mexico, and that there have been no concrete actions for the strengthening of basic rights. They affirmed that the lack of institutionalized policies, dedicated to the exertion of human rights, as a central axis through the three levels of government “limits the efforts made by the Fox administration, in a task of chiaroscuros in which the discourse does not always line up with the actions.”

In October, in the context of the commemoration of the 37th anniversary of the massacre in Tlatelolco on October 2nd, 1968, Amnesty International, The National Network of Human Rights: Every Right for Everyone, the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center, and the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights had already denounced that “this government failed in the possibility of serving justice for the crimes of the past, the student massacres in 1968 and 1971 and the hundreds of disappeared in the Dirty War. Fox made small gestures, spoke a lot, made promises, and did not see them through. (…) In this government, impunity continues, as it did with its PRI predecessors, and many of the same human rights violations we saw in the past continue to occur: forced disappearances, illegal detentions, executions, torture, kidnapping, and many more.”

A theme that gained major relevance in the media is related to the fact that Mexico was classified, in the publication of Journalists Without Borders, as the second worst nation in the continent in terms of freedom of expression. According to the Latin American Federation of Journalists, Mexico is at the head of the list of countries in the region in the number of aggressions against reporters, with 52 murders and 2 disappearances in the last 22 years. In the past 18 months, 8 Mexican journalists were murdered, and another disappeared. In the case of Chiapas, according to Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (October 8) “the practice of the profession of journalism in our state is legally limited by sanctions within the State Penal Code on Defamation and Calumny, called the “Gag Law,” enacted in May of 2004.” Two concerning cases have occurred: at the end of October, the journalist Concepción Villafuerte, director of the newspaper “La Foja Coleta” reported that she had received threats. Members of the Municipal Police of San Cristóbal de Las Casas stated that they received orders to eliminate her and they explained in detail the threats and abuses they suffered from their superiors. Villafuerte was sued by the chief of the city’s police force for defamation. In October, the General Director of the newspaper EL ORBE and the Weekly EL ORBE, C.P. Enrique Zamora Cruz was detained after publishing information critical of the situation in the area affected by Hurricane Stan.