2005

02/01/2006

ANALYSIS: Mexico-Chiapas, On the Road to the Elections

28/04/2006Saturday October 15, 2005, Pueblo Hidalgo, Montaña, Guerrero.

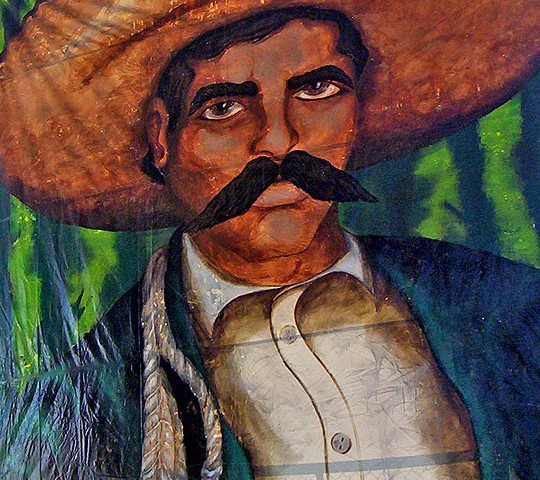

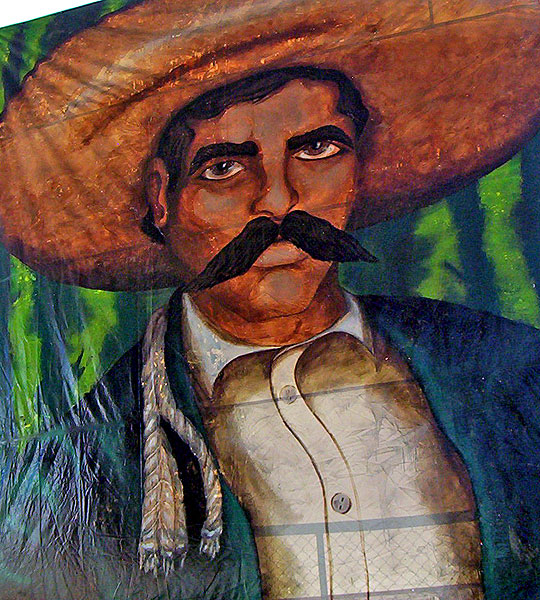

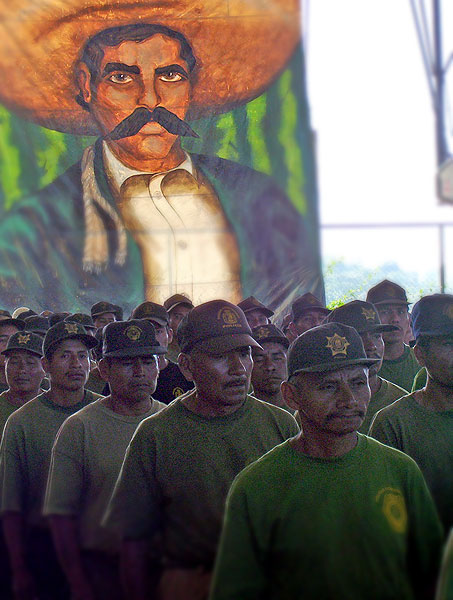

Two hundred police officers march to the rhythm of the bands, under the severe gaze and the large moustache of Emiliano Zapata (an immense mural on the ceiling), before a crowd of five hundred people: representatives of communities, indigenous, social and non-governmental organizations. After the honoring of the flag, everyone sings the Mexican national anthem, first in Tlapaneco (one of the four indigenous languages spoken in the state), then in Spanish.

This could be any official event… But this one has a different meaning. These police officers are not “official.” These two hundred uniformed men are “community police.” In addition to their own work, they ensure the safety of the people, as they volunteer out of a sense of service and duty.

When the Criminals Decided the Law

It all began in 1992. In the Costa-Montaña region (Coast-Mountain) of Guerrero, the incidence of assault, robbery, kidnapping, rape, theft of livestock, and activities related to drug trafficking was steadily increasing. All the ingredients were together for the strengthening of criminal gangs: the level of extreme poverty, the decline in prices of agricultural products, the cultivation and trafficking of drugs, the poor condition of the means of communication (even at times totally lacking), as well as others. The population lived with constant fear and felt that the police were unable to control the delinquents and were even complicit with them in some cases.

Faced with these circumstances, the Parish of Santa Cruz del Rincón, in the municipality of Malinaltepec, called on the community and religious authorities to analyze the conditions and needs of the towns of the region. Coffee and corn producing organizations joined the effort, along with the Consejo 500 Años de Resistencia Indígena, Negra y Popular (Council of 500 Years of Indigenous, Black and Popular Resistance), which was initially created to coordinate protests against the five hundred years celebration of the Spanish Conquest.

Through lengthy discussions, thirty-six communities joined forces to found the “Community Police” on October 15, 1995. The Community Police, made up exclusively of volunteers, began to guard the roads and accompany trucks to prevent assaults. When they detained a delinquent, they turned them over to the official authorities. They began to note, however, that those detainees who had money could buy their freedom, and those who did spend some time in prison were often repeat offenders.

From Security to Reeducation

In 1997, in the face of this balance, the communities decided it was necessary to expand the Community Police system to include the process of imparting justice. The “Community System of Security, Justice & Reeducation” (SSJRC) was created for this purpose. Independent of indigenous and religious groups or economic interests, the SSJRC has three basic principles:

- Investigation before proceeding;

- Conciliation before sentencing;

- Reeducation before punishing.

This system of justice bears many similarities to that of the Zapatista “Caracoles” in Chiapas: “We believe that there is another way of applying justice. We do not look in a book to see which article was violated, (…) which is how the official justice system works. There is no money in it (…) The first step is the investigation, going and seeing what happened, we work with a great deal of conciliation, with mediation, being neutral. Imparting justice without the money of power. (…) We work a lot with the customs and practices (usos y costumbres). If someone stole, we need to understand why they stole, because everybody is needed” (Good Government Council of Morelia- SIPAZ Interview, March 2005).

The SSJRC states that the delinquent is not the person to “eliminate” so that the community can “live in peace.” When a crime is committed, everyone is a victim, not only those affected, but also the delinquent (because he lost the most important part of the indigenous worldview: his honor, his word, everything that makes him a man). The community is also the victim (because “they did not realize that this person was headed down a bad path” and “they were unable to set him in a better direction.”) In this vision, justice and security are everyone’s responsibility and it is about looking for ways to restore the damaged relationship, to restore the social fabric, or structure.

When the police detain a delinquent, they take him to the corresponding community authority who then decides the adequate sanction. The delinquent does not have the right to an attorney, unless the service is free, to assure that all are equal before justice, regardless of whether they have money or not. The delinquent can be defended by a family member, or by himself. Reconciliation between the victim and the aggressor is always the priority, as well as reparation of the damage. There are no prisons, because it is believed that they do not serve to reeducate the delinquents, nor do they do anything positive for the communities. Depending on the severity of the offense, the delinquent has to provide community service, receiving food from the community, with no pay. Delinquents work in the construction of roads, bridges, and public buildings… “If we decide that the reeducated need to do work for the community, it is not with a vision of having slaves, rather it is with the idea that they must regain their work ethic, and the education that they somehow didn’t receive,” stated Regional Commander Bruno Plácido Valerio (La Jornada- 9/28/2005). Additionally, the delinquents receive “lectures” from the elders (who are the keepers of the community history and experience). If a delinquent commits another offense, their community service sentence is doubled.

A System of Justice Built from Below

Today, the SSJRC is applied in sixty-three communities (Mixtecas, Tlapanecas, Nahuas, and Mestizas) in the six municipalities of the Costa-Montaña, representing about 100,000 people. Each community has a commander and community police officers, chosen in the assembly for three years. There are 612 community police officers responsible for guarding the roads and detaining delinquents. Of the sixty-three community commanders, six are elected as regional commanders and they work in the “Executive Committee” of the Community Police for one year. This reproduces the community authorities at a regional level.

When the Community Police detain a delinquent, the offender is given the choice of having the case presented to the Public Minister or to the community justice system. The majority of delinquents opt for the latter, because, in addition to other reasons, cases are dealt with more rapidly.

The justice is administered by various authorities depending on the offense. Minor offenses, such as conflicts among intoxicated persons, petty theft, and domestic disputes are handled by the individual community commissioner of the place where the crime was committed. For more serious offenses (violent assault, drug trafficking, rape, murder…), the “Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities” (CRAC) was created. This is an agency composed of six regional commissioners who act as judges. Extremely serious crimes are handled by the “Regional Assembly of Community Authorities,” made up of all the security and justice authorities of the sixty-three communities. This organization also deals with other issues such as the relationship with the municipal, state, and federal governments, the election of the members of the CRAC and the Executive Committee, as well as the approval and modification of internal regulations.

The Repression Suffered in the Past Ten Years

In the past ten years, the effect of the SSJRC has been highly positive: they have achieved the reduction of crime in the region by 90-95%. According to the report presented at the anniversary celebration, of the 1,484 cases processed from 1997-2005:

- 1,203 were resolved through acts of reconciliation or reeducation processes;

- 247 cases remain open;

- 34 delinquents remain fugitives.

These results have generated a great deal of curiosity and interest in recent years, especially when compared to the Mexican justice system and its many shortcomings: “The existence of a fundamental problem in the penal justice system in Mexico is reflected in the fact, corroborated by the 2002 reports of the majority of the state human rights commissions and the National Human Rights Commission, that the respective state justice authorities are the officials most often responsible for the violation of human rights.” (Diagnostic Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Mexico- Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights of the United Nations in Mexico- 2003)

The communities support the legality of the SSJRC with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), signed by Mexico in 1990. This agreement recognizes the right to self-determination of indigenous communities, as do the articles 2, 4, 115, and 139 of the Mexican Constitution and the Organic Municipal Law of Guerrero. They add that the system is legitimized by the communities themselves. These arguments do not appear to convince the state government, which has oscillated between tolerance and repression over the past ten years. Initially, it was well received, when it was simply the police officers turning over delinquents to the official justice system. In fact, the Government of Guerrero gave the SSJRC weapons in 1997, and the Mexican Army trained the officers from 1995-1997.

However, when the organization decided to start imparting justice, which is to say, developing a parallel system without appealing to the state, the repression increased: arrests of commissioners accusing them of illegal deprivation of freedom, periodic disarming of community police by the Army since 1996, fabrication of offenses and detention of the Parish Priest of Santa Cruz del Rincón, advisor, and of Bruno Plácido Valerio in 2000, as well as threats against other participants. To date, the proposals for the regulation of the Community Police by the state government have been systematically rejected by the people.

The Limitations of the Community System of Security, Justice and Reeducation

“In these ten years, we have advanced a lot, and we have stumbled a lot,” stated the commissioner Cirino Placido Valerio (11th Anniversary of the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center of the Mountain on March 6th, 2005). Today, this model of alternative security and justice is confronted with certain limitations. The communities are addressing the priority of seeking subsistence alternatives. Many migrate to the north of Mexico or to the United States, especially the young people. Some start to question the lack of salaries for the police officers. It was agreed that the community needed to give more support to their police.

In some places, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find volunteers willing to serve as police officers, because the men cannot do so, or because they are discouraged by the risks (five lives have already been lost, by police officers and commanders). There are communities that are less involved and elders who no longer give the lectures to the delinquents. “There is no longer the same whole-hearted and courageous participation,” affirms Gelasio Barrera, a regional commander. (La Jornada- 9/28/2005)

Another concern is the search for funds to cover the operative costs (gas, maintenance of vehicles, radios, etc.) in order to maintain independence from political parties and government agencies. A civil association was created to receive funds from both public and private sources.

Another challenge is related to the role of women within the SSJRC. In 1998, five women were invited to support the CRAC to better address cases in which the offenders or the victims were women. But the internal discrimination by the men discouraged several women from continuing to participate. In the context of the 10th anniversary, the CRAC once again invited women to participate, not only in the regional organization, but also within each community. The women responded: “The goal of our participation is to create a Community Police that considers our views and listens to our voices, because in the end, the struggle is collective and in this collectivity we are the other half that seeks, along with our compañeros, a better quality of life where our rights as indigenous communities are respected.”

Another criticism of the SSJRC is the difference between the positive interpretation of human rights and the worldview of the indigenous communities. For example, for the SSJRC the crime of “witchcraft” exists, while it is not recognized by the positive interpretation of human rights. It is important to note that the normative systems are not set. The CRAC reclaims the customs and practices to discuss them and adapt them to the reality that the communities live in today: “The indigenous communities (…) have turned their gaze, their emotions, and their intelligence to their own source of culture and justice, and they have figured out how to readapt and reenergize their normative systems to be able to live as indigenous peoples and as Mexican citizens in the third millennium. (…) Tradition is recreated to adapt it to a western mold with a constitutional foundation and international legislation.” (Tenth Report of Tlachinollan)

After Ten Years, Balance and New Challenges

The anniversary of the Community Police served as a pretext for the analysis of the path it has taken, the recognition of the mistakes that have been made, and to set goals for the future. “Something that has roots and that is born from below, that has life and legitimacy has a future, it is not artificial, we have had difficulties, but we have also had great results, everyday we improve. The police have no hurry to grow. There is great demand to join, but that is decided by the people in assembly, it is not the decision of an authority,” commented Cirino Plácido Valerio. It was resolved that they would consider security and justice in a more global framework, embracing the defense of territory, the search for nutritional sovereignty, the implementation of fair trade, and the active participation of women in all of these areas. They resolved to think about the construction of a new popular nation project. A number of references were made to the Zapatistas, stating the need to apply the San Andrés Accords, to share the experiences of self-determination of the peoples and to support the Other Campaign proposed by the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation). They stressed the need to continue to reclaim the communities’ own forms of organization outside of the political parties, to look within the communities for solutions to political, agrarian, and educational problems, recuperating the ability to organize as communities at the regional level. They stressed the importance of recuperating historic memory for the education of the youth.

The challenges are great and the path ahead of them is long. In many parts of Mexico, the community system of the indigenous peoples is more difficult to maintain. But, while ruptures in the social fabric of some communities are apparent, new models and proposals are being presented by the communities themselves. “While the public policies of assistance (individual, free trade, migration, drug trafficking, and consumer culture) are causing damages to the identity, subsistence and traditional organization of the indigenous communities, opposite projects like the Community System of Security, Justice & Reeducation act as counterbalances. In the face of this situation we can expect that the identity, culture, and organization of many indigenous peoples and communities can break down, deteriorate or even disappear. Nevertheless, we can also see that many peoples and communities will not only survive, but will come out of it all stronger, with self-governing structures of organization and articulation in different areas and levels, becoming the creators of their own destiny.” (XI Tlachinollan Report)

In Guerrero, like in Chiapas, alternative systems of life that are built from below seek more and more integrity to continue and develop. These systems undertake sustenance as well as justice, education, and health. Furthermore, they perceive the necessity to articulate themselves not only at the local level, but also at the regional, state, national and international levels. Each model of autonomy has its own history and its own characteristics and cannot be reproduced in another context. Rather it is more about sharing information about these alternatives to learn from each other and to strengthen one another, as distinct and creative responses of the peoples in resistance.