SIPAZ Activities (mid-May to mid-August, 2023)

27/09/2023

FOCUS: Arbitrary detentions; a frequent practice, pain and injustice in Mexico

16/12/2023

I n September, the National Peace Dialogue was held in Puebla, after talks and Justice and Security Forums were held in the states in which more than 18 thousand people participated in the last ten months.

The National Peace Agenda was announced, which seeks to “transcend a culture of violence towards a culture of care and peace.” It is intended that this Agenda be made known to society in general, as well as to the presidential candidates for the 2024 elections. The agenda includes proposals for actions that can be implemented “in families, schools, communities, institutions, companies, universities and others” and that allow us to demand “governments to fulfill their role effectively and transparently.” “Peace is a joint effort of different levels and of all social sectors, it implies the sum of wills, coordination of efforts and the generosity of everyone to overcome the fear of the indolence and inefficiency of the authorities,” it further states.

Human rights: a long list of pending issues

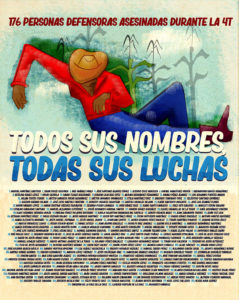

In August, human rights organizations reported that in the last year they recorded 128 human rights violations against human rights defenders. 31 of the cases were concentrated in the Mexican capital, 18 occurred in Michoacan and 12 in both Chiapas and Oaxaca. The major trends include: an increase in the number of organizations and communities attacked; an increase in human rights violations by governments of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), and an increase in those committed by the federal government, among others.

In September, Amnesty International (AI) denounced the disproportionate use of the justice system to dissuade, punish and prevent defenders from protesting to demand their rights. “Mexico is among the countries where the most murders of environmental defenders are committed, while far from the State addressing and preventing this violence, other serious violations of their human rights are being added, such as stigmatization, harassment, assaults, attacks, forced displacement and disappearances,” it declared. It stressed that “the right to protest is a fundamental means that defenders of land, territory and the environment have used to demand their rights, particularly when other institutional mechanisms have failed or have not been accessible.” This same month, Global Witness reported that, in Mexico, 31 environmental defenders were murdered in 2022, making it the third most dangerous country to be a natural resources activist.

In September, Article 19 documented 272 cases of attacks on journalists and communicators in the first half of 2023: one attack every 16 hours. With half of the cases, coverage of corruption and politics is clearly the riskiest. According to Article 19, “the State continues to be the main aggressor against the press in Mexico. During these first six months of 2023, the authorities were responsible for perpetrating 140 attacks, that is, one in every two attacks.’’ So far, the NGO has counted 2,941 cases in the current government of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO).

In September, a representation from Mexico appeared before the Committee against Forced Disappearances (CED) of the United Nations (UN) to review progress on previous recommendations. The official Mexican delegation highlighted actions regarding human identification and “strategies” in the search for vulnerable groups such as women, children, adolescents, and migrants. The CED requested several details about the so-called National Registry of Missing and Unidentified Persons (RNPDNO). For the relatives of the more than 111 thousand victims and civil organizations, the new registry seeks to reduce the figures that already exist without solving the underlying problem, to manipulate the facts for electoral purposes. The Miguel Agustín Pro Juarez Human Rights Center (ProDH) stated that it is very striking that, with so many pending issues regarding disappearances, energy is used on that, instead of putting the National Forensic Data Bank into operation or preventing the commission of these crimes. The CED declared that in the immediate future “the efforts are not giving results,” that the forensic crisis remains and was concerned about the risk that families face when searching. It also regretted the low number of criminal cases and sentences given the crisis of disappearances.

Earlier this month, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention conducted an official working visit to Mexico in September, after which it concluded that “arbitrary detention remains a widespread practice in Mexico and is too often a catalyst for ill-treatment, torture, forced disappearances and arbitrary executions”. They also pointed out that the Armed Forces, the National Guard, and state and municipal police are frequently involved in arbitrary detentions (see Focus).

Likewise, in September, the Washington Office on Latin American Affairs (WOLA) published a report titled “Militarized Transformation: Human Rights and Democratic Controls in a Context of Growing Militarization in Mexico.” It points out: “Mexico is experiencing a process of increasing militarization of civilian tasks inside and outside the scope of public security. While previous presidents presented militarization as a temporary process that would strengthen the role of civil institutions—although in practice military deployment became the permanent model, largely at the expense of prioritizing other security and justice strategies and institutions—, the current government promotes a broad long-term militarization of civilian tasks, including through the militarization of the National Guard. As their capacities and power grow, the Armed Forces do not have effective civilian controls over their actions. In terms of human rights, in the period after Felipe Calderon’s six-year term of office, there has been a reduction in the levels of serious violations attributed to the Armed Forces. However, these continue to occur. More broadly, Mexico continues to experience historic levels of violence, and the vast majority of crimes go unpunished.”

EZLN: Changes in autonomous structures and other proposals

Earlier this month, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention conducted an official working visit to Mexico in September, after which it concluded that “arbitrary detention remains a widespread practice in Mexico and is too often a catalyst for ill-treatment, torture, forced disappearances and arbitrary executions”; They also pointed out that the Armed Forces, the National Guard, and state and municipal police are frequently involved in arbitrary detentions (see Focus).

Likewise, in September, the Washington Office on Latin American Affairs (WOLA) published a report titled “Militarized Transformation: Human Rights and Democratic Controls in a Context of Growing Militarization in Mexico.” It points out: “Mexico is experiencing a process of increasing militarization of civilian tasks inside and outside the scope of public security. While previous presidents presented militarization as a temporary process that would strengthen the role of civil institutions—although in practice military deployment became the permanent model, largely at the expense of prioritizing other security and justice strategies and institutions—, the current government promotes a broad long-term militarization of civilian tasks, including through the militarization of the National Guard. As their capacities and power grow, the Armed Forces do not have effective civilian controls over their actions. In terms of human rights, in the period after Felipe Calderon’s six-year term of office, there has been a reduction in the levels of serious violations attributed to the Armed Forces. However, these continue to occur. More broadly, Mexico continues to experience historic levels of violence, and the vast majority of crimes go unpunished.”

For several weeks now, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) has been sharing statements on various topics and considerations. They are signed by the now Insurgent Captain Marcos or the Insurgent Subcommander Moises and state that the Zapatista struggle must be for the freedom of future generations, “for someone we are not going to know.” “We can now survive the storm as Zapatista communities that we are. But now it is about not only that, but about going through this and other storms that will come, going through the night, and reaching that morning, 120 years from now, where a girl begins to learn that being free is also being responsible for that freedom.’’

Subsequently, Subcommander Moises announced that they made changes to their autonomous structures when their more than 40 autonomous municipalities and the Good Government Councils (JBG) disappeared. He reported that within the framework of the 30th anniversary of the armed uprising, public celebrations will be held in the months of December 2023 and January 2024. However, he stressed that “it is our duty, at the same time as inviting you, to discourage you” because “The main cities of the southeastern Mexican state of Chiapas are in complete chaos. The municipal presidencies are occupied by what we call ‘legal hitmen’ or ‘Disorganized Crime’. There are blockades, assaults, kidnappings, protection rackets, forced recruitment, shootings. This is the effect of the patronage of the state government and the dispute over the posts that is in process. They are not political proposals that are presented, but rather criminal societies.”

Later, he announced the formation of the Local Autonomous Governments (GAL) that will both allow to address different social needs and “increase the defense and security of the peoples” and of Mother Earth. Several GALs will be organized into Zapatista Autonomous Government Collectives (CGAZ). The Assemblies of Collectives of Zapatista Autonomous Governments (ACGAZ) continue. The proposal, he explained, is that “we have prepared ourselves so that our people survive, even if isolated from each other.”

Another statement explained why they decided to remove the previous structures. “It was seen that the structure of how it was governed, a pyramid, is not the way. It’s not from below, it’s from above. If Zapatismo were only the EZLN, well, it is easy to give orders. But the government must be civil, not military. Then the people have to find their way, their way and their time. Where and when. The military should only be for defense,” said Subcommander Moises. Another consideration was that they analyzed that the previous structure was not adequate for the new situation: “If you see that it is going to rain or that the first drops are already falling and the sky is black like a politician’s soul, then you take out your plastic and look for where you can shelter,” he said, explaining that “with MAREZ and JBG we won’t be able to face the storm.”

CHIAPAS: Violence continues to spread

The dispute over the territory located on the border with Guatemala and the Sierra de Chiapas, which began more than two years ago, has intensified in recent months. Armed confrontations, murders, disappearances, forced displacement, road blockades, forced recruitment and protection rackets are a constant in that area. Highlighting the seriousness of the situation, in September, some five thousand teachers who serve just over 150 thousand students of all educational levels in the municipalities of the mountain and border areas decided to suspend work. “Given the negligence and absenteeism of the competent authorities to confront criminal acts committed by criminal groups (…) until they guarantee us the necessary social security conditions, we will not return to our daily work,” they declared.

Other areas also filed complaints and demanded the intervention of the authorities due to violence linked to an apparent heating up of the turf wars in their territories. That was the case of the Nueva Palestina community in the municipality of Ocosingo in September (it is located on the border line with Guatemala, but further north than the previously mentioned areas); and from the municipality of Tila (even further north of the state) in October.

Other conflict situations seem to respond to a logic that is more of an electoral political nature. In September and for several weeks, residents of the municipality of Oxchuc, belonging to the “Community Front for Self-Determination” partially or totally blocked the stretch of road between San Cristobal de Las Casas and Ocosingo. They denounce that for months the ruling issued by the Electoral Court of the State of Chiapas has not been complied with, “indicating the reinstatement of elections under internal regulatory systems of the municipality of Oxchuc.” Something similar—between a blockade and other forms of violence—occurred in October in the municipality of Altamirano, where two groups have disputed municipal power since the 2018 elections.

Seeking alternatives to violence

Complaints from different sectors, marches and pilgrimages have multiplied to call for a stop to violence. In August, thousands of the faithful of the Catholic Church from the Ch’ol and southeastern areas of the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas made a pilgrimage for Peace in Palenque and Comitan. In the case of the Ch’ol area, the pilgrims questioned the Maya Train Project: “Who will be the true beneficiaries of the project? (…) How will the families of our peoples benefit? Will there be a true respect and care for our Mother Earth?” Likewise, they denounced the failures of the health system, “the impunity and corruption of the judicial system” and the fact that in “political parties, the search for satisfying personal or group interests prevails, which perverts the noble goal of politics and distances them from the true needs and legitimate expectations of the people.” In the case of the Southeast Zone, the Believing People pointed out “the presence of organized crime that operates with total impunity, with the objective of controlling the territory, exploiting its natural wealth and collecting protection money, violating human rights. of the communities”; as well as “the conversion of our territories and communities into battlefields.”

In September, several human rights networks denounced the violence that has worsened in Frontera Comalapa and other border municipalities. They stated that “it is notorious that far from conflicts being resolved (…), the conditions for the growth and expansion of these criminal groups continue to be allowed.” Consequently, “the population (…) currently lives hostage to criminal groups: the circulation of people and vehicles is controlled through checkpoints and blockades placed on the roads; Adolescent men, from the age of 13, are recruited for scouting activities (surveillance and information collection); young women from the locality and from Central American countries are victims of trafficking and sexual exploitation.” In addition, the networks said that “since the arrival of the Armed Forces to the scene, there is no certainty of their role in the context. (…) The abandonment and repeated omissions of the State at all levels to guarantee the integrity and security of the population of the region and the minimization of the situation by the federal administration, place the civilian population, journalists and human rights defenders at greater risk and vulnerability.”

Similarly, in September, the Dioceses of San Cristobal de Las Casas and Tapachula expressed their concern about what is happening. “Criminal groups have taken over our territory and we find ourselves in a state of siege, with social psychosis, under narco blockades that use civil society as a human shield,” they denounced in Tapachula, while in San Cristobal, the statement was issued titled “Chiapas Torn by Organized Crime”, in which the lack of response from the authorities was denounced that “puts human integrity at risk and shows us a failed state that has been overcome and/or colluded with criminal groups.”

OAXACA: Conflicting views on the situation in the state

In November, the governor of Oaxaca, Salomon Jara Cruz, presented his first government report, highlighting among his achievements that for the first time in the history of the state there is a joint cabinet and that he has presented initiatives to revoke the mandate and austerity to eliminate the luxuries and excesses of previous governments. The event took place in the Guelaguetza Auditorium as the venue had to be changed due to teacher protests. Jara Cruz reported that in his first year in office he visited 376 of the 500 municipalities in the state to directly address the needs of the people. He also declared that “in the framework of the awakening of the south-east of Mexico, while the country grows at an average rate of 3.6%, our state presents rates of economic and industrial activity above 10%.” As regards security, he affirmed that his government has managed to reduce the growth rates of many of the most common crimes.

On the other hand, in October, civil organizations were concerned about security policy, the lack of state mechanisms to confront the migration crisis, violence against human rights defenders, and the links between organized crime and armed groups that defend political, agrarian and economic power, and the dispute for territorial control between organized crime groups. They stressed “the urgency for the State’s actions to be from an intersectional, multicultural perspective and action and not from a sexist, racial and discrimination logic. They demanded that the Mexican State guarantee access to justice, truth and comprehensive reparation with the effective participation of the victims.”

Likewise, in October, the organization EDUCA; Services for an Alternative Education C.A. (Servicios para una Educación Alternativa A.C.) reported that Oaxaca is the state with the most defenders murdered in the country between December 2018 and October 2023, with 41 cases. Guerrero appears in second place (29), Michoacan in third (18) and Chiapas in fourth (14). In Oaxaca, of the total of 54 incidents registered since December 2022, the Isthmus region stands out, with 46 attacks ranging from harassment, criminalization, to physical attacks and murders. The main reported aggressors are state authorities with 44% of the cases and federal authorities with 22% (“the Navy and National Guard are players reported mainly in the Isthmus within the framework of the imposition of the development project of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec”, they stated).

GUERRERO: “a State without Health, Education or Security”

In August, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center published a bulletin on the situation in Guerrero titled “A State without Health, Education or Security.” It says that “our State is in second place [in poverty] after Chiapas, with two million 173 thousand people living in poverty.” Although the figures reflect a decrease in the number of people in poverty or extreme poverty, “the concrete situation is that the majority of families in Guerrero face extremely serious problems because they barely survive daily” due to the rise in prices of the basic foodstuffs. The situation of access to health and education services is equally critical. “The ancestral abandonment of governments is not reversed with social programs, because they do not fundamentally attack the inequality that is rooted and that requires a more comprehensive and long-term treatment,” the bulletin emphasizes. Likewise, Tlachinollan lamented the “serious security crisis due to the collusion of municipal governments with organized crime. (…) In Guerrero the poor population dies due to lack of medical care; children and youth sink into illiteracy and we are all left defenseless before the de facto power that criminal groups that are embedded in the spheres of public power are exercising.”

In November, Tlachinollan also denounced that “the territorial dispute that is taking place between rival groups in the main cities, especially in Acapulco, is spreading to small municipalities (…) Several murders have occurred in the municipalities and there are several cases of missing persons. Even though the municipal authorities are aware of this situation, they remain on the sidelines, lower their guard and choose to establish an alliance with criminals in exchange for protection.” Furthermore, several agrarian authorities commented to Tlachinollan that “the presence of the National Guard was no guarantee that the violence would abate; on the contrary, it would represent a risk for the population organizing to defend their territory. They are very aware that, in other years, the army entered the communities, detained heads of families, tortured and murdered several people.”

Impunity remains another deep-seated problem. On the ninth anniversary of the disappearance of the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Normal School in Iguala, in September, AMLO held a meeting with parents of the missing student teachers that ended in a disagreement. AMLO acknowledged that the relatives did not want to receive the report and accepted “differences” because they insist that the Army is not cooperating. “I do not agree with them because the Army has provided all the information they have and has helped a lot,” he declared. The mothers and fathers of the 43 continue to demand the information that they believe the Mexican Army has hidden and that those responsible be punished so that justice is done.

In terms of response to violence, in October, the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities-Community Police (CRAC-PC) celebrated its 28th anniversary, during which an event was held in the municipality of Tlacoapa. Tlachinollan recalled: “The peoples of the Mountain Coast (…) were the ones who took this difficult task of guaranteeing the life and safety of the people of the communities into their hands. They rescued their legal customs that are community laws, recovered their regulatory systems and promoted community organization. Its community justice system is supported by regional and community assemblies, from which the rules and guidelines emanate that are fully complied with by the coordinators of the CRAC-PC and other authorities. With this great task on its shoulders, the community police have managed to reduce the high crime rates that existed in the region and be a successful experience of what it means to serve and defend the rights of the people.”