SIPAZ Activities (April – June 2006)

31/07/20062006

01/01/2007Between July and August 2006, three deaths were denounced in prisons in Chiapas. Two happened in “El Amate” (CERESO -Centre for Social Rehabilitation- number 5) and one in Chiapa de Corzo. All of them were justified by the authorities and by the Public Prosecutor as natural deaths, denying the possibility of torture even though the autopsies revealed suspicious elements. For instance, José Gabriel Velázquez Pérez, a 34 year old carpenter who died on the 27th of August, suffered trauma and massive hemorrhage in his abdomen, most likely caused by someone beating him. He had been arrested in his mother’s house; during his arrest, tear gas was used; and during his transfer to the prison in Chiapa de Corzo he was beaten by police officers. According to José’s wife, he told her: “Take me out of here, I’m dying, I need oxygen, they’re beating me, get me out of here, I’m being beaten by the police officers.” His death was made public a few hours later.

These are examples of a very widespread phenomenon. Several international organizations, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the United Nations (UN), have signaled that the culture of torture is still present in Mexico. It is a phenomenon very difficult to fight since it is institutionalized and directly linked to the practice of power in many organizations of the Mexican state. The judicial and prison systems are not an exception: they show serious contradictions with Mexican laws and fundamental rights of imprisoned people recognized internationally.

Impunity: An Endemic Issue

The use of torture is partly caused by shortcomings in the criminal and forensic investigation systems. According to the report published in 2001 by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, Dato Param Cumaraswamy, the impunity in Mexico reaches percentages of “between 95% and 98%.” He describes this situation as endemic and believes it means the denial of the rule of law. A number of NGOs, the UN and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights(1) have also expressed their concern about the human rights violations that promote and guarantee impunity in Mexico, urging the Mexican authorities to put an end to this situation.

Amnesty International describes several characteristics of the impunity in cases of human rights violations. First of all are the limits placed by the way civil cases are handled by the prosecutor. Second, the fact that human rights violations involving members of the army are judged in military courts. In June 1994, three Tzeltal women of 12, 15 and 17 years old were illegally detained, raped and tortured near Altamirano, Chiapas. None of the perpetrators (soldiers, according to the witnesses) have been judged, so the case has been taken to the Interamerican Court of Human Rights. Third, the judges’ acceptance of forced confessions as evidence.

Torture for the purpose of getting forced confessions is a common practice in Mexico. For example, Gonzalo Sánchez López and Manuel Gómez Sántiz were arrested and beaten by police officers on the 4th of July, 2006. According to their testimonies, the police officers put plastic bags on their heads, causing asphyxia and making Manuel faint. Finally, they signed a confession. Manuel was taken to the town where the homicide took place, and the police officers put a gun in his mouth to force him to inform where the body was hidden. It was never found. Gonzalo and Manuel are still in prison.

Another worrying sign, denounced by Amnesty International, is the lack of access to justice for the indigenous population. Even if 10% of the Mexican population (30% in Chiapas, with most of the imprisoned population being indigenous people) is indigenous and justice is theoretically guaranteed by Mexican law, access to translators and interpreters in indigenous languages is very deficient.

There are more barriers to the access to justice, such as inadequate legal defense. Many of the public defenders are not well trained; they earn low salaries, are overworked and are not independent enough from the Public Ministry. Neither are the judges independent: the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers denounced after his visit to Mexico in 2001 that between 50% and 70% of the judges are corrupt, representing a “terrible social issue.” The influence of “narco” (drug trafficking) is seriously damaging the judiciary system, corrupting all its levels.

Little Progress

When President Fox (2000-2006) was sworn in, he promised to respect human rights and to strengthen the rule of law. He even announced a reform to make human rights more evident in the Constitution. Amnesty International expressed their approval of such plans. However, as his term of office is coming to an end, it is obvious that impunity has prevailed and continues prevailing today. The announced measures have not been taken, as Nigel Rodley, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, denounced in March 2002.

The little progress made during Fox’s presidency was criticized again by the new Special Rapporteur on Torture, Manfred Nowak, in March 2006, when he wrote the recommendations for the improvement in the observance of the Mexican state’s duties as a party state of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. He alleged that very few of the recommendations made by the Special Rapporteur in 1997 have been applied by the Mexican government.

Confessions made in front of police officers, and not a judge, are still accepted as evidence, even though Fox’s cabinet promoted a constitutional reform to establish confessions made in front of a judge as the only ones acceptable. This reform was rejected by the Senate, as well as the proposal to ensure that presumption of innocence is respected in cases linked to organized crime. Another example of the recommendations that were never fulfilled is the elimination of the arraigo(2), a figure very broadly used in Mexico which permits the police to keep a person under arrest for a period of up to 60 days, once this person has been presented to an attorney, even if there is no proof of responsibility or no crime at all. It is important to remember that, according to Human Rights Watch, more than 40% of the prisoners in Mexican prisons are in “preventive prison”: they’ve never been found guilty and they’re waiting for a trial.

The following are some other ignored recommendations: compensations to victims of torture by public officers, access to independent doctors (both established by the Istanbul Protocol), independence of judges in trials against public officers and a legal time limitation for investigations concerning human rights (including torture). There is a situation of de facto amnesty or impunity for police and army officers violating human rights, also in cases where human rights defenders are threatened and harassed.

Amnesty International denounces extrajudiciary executions and the disappearance of people, which happen without anyone being taken to trial. Arbitrary detentions, torture and ill-treatments by public officers are still common in Mexico. Many detainees are dying as a result of torture they suffered during their arrest. On the 22nd of July, the Tzotzil indigenous man Jesús Hernández Pérez died in the prison of El Amate. His family was told that his last meal “had not agreed with him” and he had subsequently died. However, his widow saw he had haematomas and scratches on his face. She believes it is obvious that he had suffered a violent death, which was finally confirmed by his death certificate. Nevertheless, his body was immediately buried, even if it is legally prescribed that exhaustive research be done when people under the custody of the State die. The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Centre has demanded an investigation about these events.

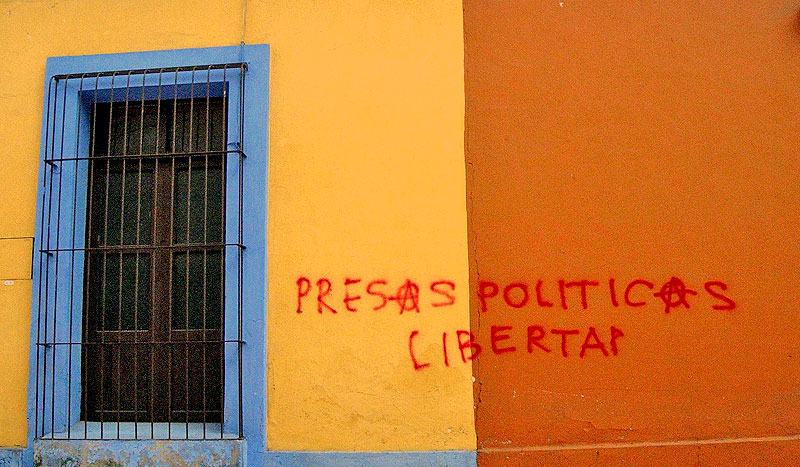

The Symptomatic Existence of Political Prisoners

“Nothing is more revealing about the situation of human rights in a certain country than the existence of political prisoners”, said Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Burma. The exact number of political prisoners in Mexico today remains unknown. It depends on the definition of the terms “political prisoner” and “prisoner of conscience.” A political prisoner is a person kept in prison or under any other kind of arrest because his or her ideas challenge or menace the established political system. The term “prisoner of conscience” includes both political prisoners and people imprisoned for their religious or philosophical beliefs.

According to the list of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience compiled by the Cerezo Committee, there are 395 prisoners of this kind in Mexico(3). In Chiapas there are around 50 of them(4), although many more consider themselves prisoners of conscience(5). Political prisoners are often members and leaders of social organizations, or people involved in political activities in some way. They are often accused of kidnappings or homicides (crimes fabricated by the authorities) and forced to declare themselves guilty in front of a judge.

Being a political prisoner can be an advantage, compared to the vulnerability and isolation suffered by other prisoners. In the Cereso #14, prison of “El Amate”, several prisoners that claim they are imprisoned for supporting the Zapatista Army (EZLN) and La Otra Campaña have organized themselves under the name of “La Voz del Amate”, the Voice of El Amate. It is the continuation of “La Voz de Cerro Hueco” (Cerro Hueco is the name of an old prison, now closed), which was created as a response to the massive imprisonments after the Zapatista uprising on 1994. Since January 2006, this group of prisoners has held protests against their detention, asking for recognition of their rights as political prisoners. According to human rights organizations, the prison authorities have encouraged other prisoners to harass members of “La Voz del Amate.”

The Other Campaign has prioritized the issue of the defense and liberation of political prisoners, especially after the events in Atenco last May. During his national tour, Delegate Zero (Subcomandante Marcos) has visited several prisons.

Worrying Conditions inside the Prisons

The conditions inside the prisons are far from legal. In many of them there are problems of overpopulation, prisoners suffer violence, the staff is not properly trained and there are no adequate sanitary facilities. It is very alarming that inmates are being hired to act as guardians. There is usually a parallel power tolerated by the prison authorities, with posts held by the prisoners (the “precisos“, for instance). Other worrying aspects are corruption (which undermines authority and produces abuses) and violent confrontations among adverse factions, linked to drug trafficking, inside the prisons. (6)

Mexican and international human rights organizations continue their struggle to make the prison system’s severe deficiencies more visible. However, there have not been big changes in the government’s policies, nor in the public opinion’s perception. In both areas prisoners are still perceived as guilty of breaking the social order and therefore they have to pay for what they have done.

There are also shortages in the attention given to imprisoned people, in social and psychological questions. From the very moment of their detention, they suffer a long and painful chain of injustices, which includes ill-treatments and torture, and which does not always produce the solidarity that is needed from their families and organizations. After this recurring chain of suffering, sometimes for years, rehabilitation and the recovery of a “normal” life in freedom is not likely to happen.

Although the Mexican legal system acknowledges the priority of the international treaties signed by the government in its Constitution (Art. 133), and therefore acknowledges several conventions and treaties regarding human rights of imprisoned people and the prohibition of torture, practice is far from what these conventions dictate. It is said that prisons are a reflection of a society, which should lead us to deeper considerations on the matter.(7)

- The Interamerican Court of Human Rights is part of the Interamerican system for protection of Human Rights. It interprets and applies the American Convention on Human Rights. (Return…)

- So far, only the state of Chihuahua has declared the arraigo unconstitutional. (Return…)

- “Mexico: Eliminating arraigo will be an important step towards protecting human rights“ – Amnesty International (Return…)

- “LISTA DE PRESOS POLÍTICOS Y DE CONCIENCIA EN MÉXICO“ – Limeddh / Comité Cerezo (In spanish) (Return…)

- “Encuentro Nacional por la Libertad de los Presos Políticos“ – Blog Zapateando (In spanish) (Return…)

- Read the SIPAZ report from May 1999 (Return…)

- “Mexico Prison Conditions” – Campaign Save a Life (Return…)