2006

02/01/2007

ANALYSIS: Mexico – A year after the 2006 elections

31/08/2007 Every day the state of Chiapas serves as an exit, stopover, return or final destination for hundreds of migrants. Here in the southern borderland of Mexico, Central Americans enter and cross the state in search of a better life in the United States. Many are caught by the Mexican authorities and forced to return home. Others make it further north. In the final stage, a small percentage will succeed in crossing the U.S. border, only to find themselves in a reality very different from the “American Dream” that brought them here.

Every day the state of Chiapas serves as an exit, stopover, return or final destination for hundreds of migrants. Here in the southern borderland of Mexico, Central Americans enter and cross the state in search of a better life in the United States. Many are caught by the Mexican authorities and forced to return home. Others make it further north. In the final stage, a small percentage will succeed in crossing the U.S. border, only to find themselves in a reality very different from the “American Dream” that brought them here.

(website of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection – www.cbp.gov)

The last five years has seen the exponential growth of a more recent phenomenon – large numbers of Chiapanecos are leaving their towns and communities to seek work elsewhere in the country or in the United States.

Mexican emigration toward the North: a not so new phenomenon

An example of this is the Bracero Program that began in 1942 when the U.S. invited Mexican workers to work in the countryside, following the labour shortage in the wake of the Second World War. At the request of the farmers, the program was prolonged into the 60’s.

“Between 1942 and 1964 the Bracero Program brought over an average of more than 200,000 workers a year. The majority of labourers were concentrated in Texas, California, Arkansas, Arizona and New Mexico. The program ended in 1964 amidst controversy and consequently was never replaced with another interchange of workers. The abrupt conclusion of this program resulted in a new era of mostly illegal immigration from Mexico. This new era began slowly, thanks to Mexico’s economic growth in the 60’s. In addition, in 1965 Mexico began a program of industrialization along the border, known as the Maquiladora Program, with the specific aim of creating jobs for laid-off immigrants. However, in the early 70’s the flow of immigrants began to speed up again.“(1).

Migration “without papers”

Once the Bracero program was closed down, and there was no longer the possibility of working legally (albeit temporarily) in the U.S., illegal migration began to rise with ever-increasing speed. Today there is an estimated 12 million Latin American illegal immigrants in the United States, over half of which are Mexican.

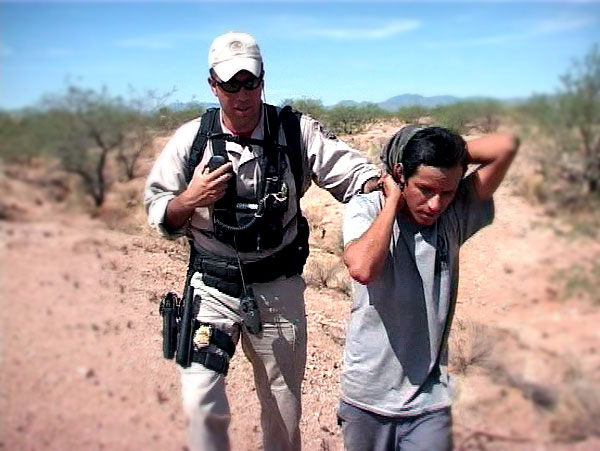

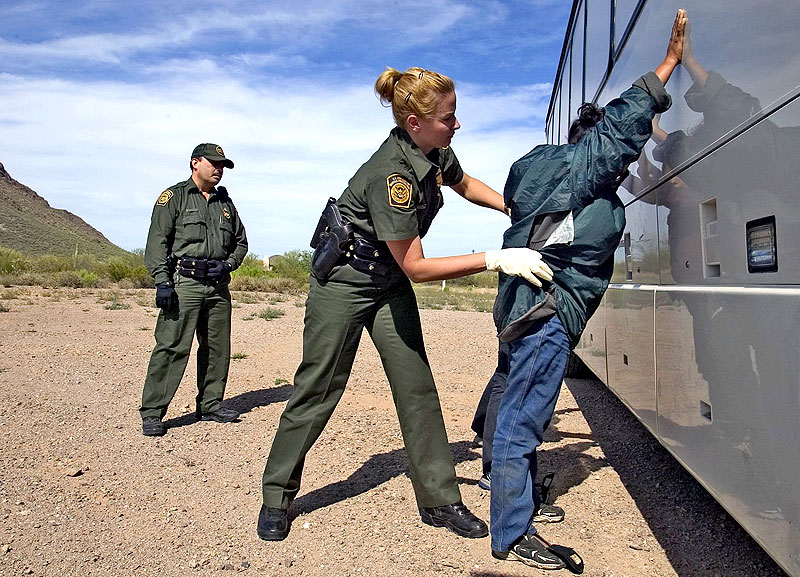

The United States has tried to stem the flow of migrants by introducing stricter laws to make it difficult to enter and stay in the country, keeping a closer watch at the border, and constructing walls. Border Patrol, the police force created in 1924, has been accused of multiple violations of human rights, including the killing of migrants. Human Rights Watch described them in 1998: “Reports show the disturbing image of an agency that is out of control: dozens of people killed or wounded in Border Patrol shootings; violations of the U.S. Justice Department’s policies regarding the use of lethal weapons; sexual violence; beatings and abuse of those arrested; and a code of silence by which the patrolling agents refuse to testify against their colleagues, thereby giving them virtual impunity, whatever their actions may be.”(2). Moreover, in 2005 the Minutemen Project was created, a group of armed civilian volunteers who, believing that the U.S. government was not keeping a close enough vigil on the border, took it into their own hands to keep watch along the border and warn Border Patrol of illegal aliens attempting to cross into the country. In spite of being prohibited from making any kind of contact with migrants, they have been accused of harassing and killing several migrants.

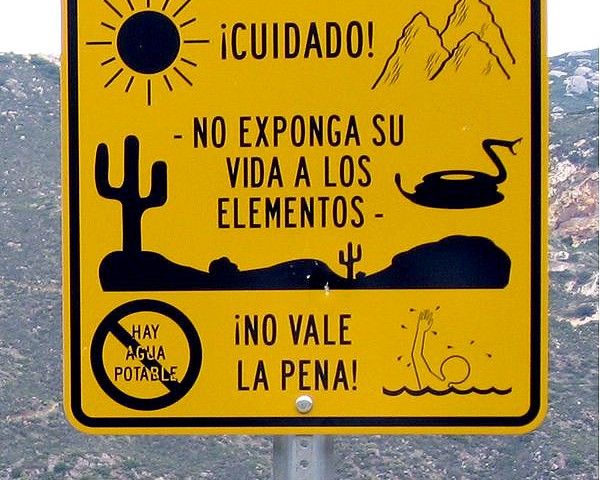

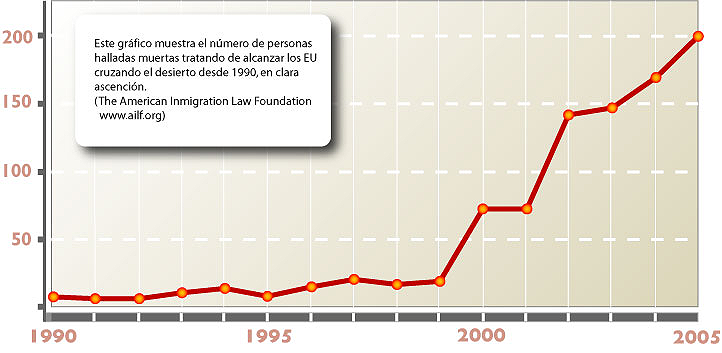

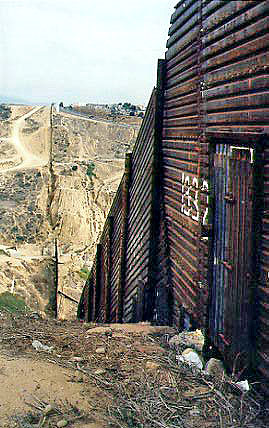

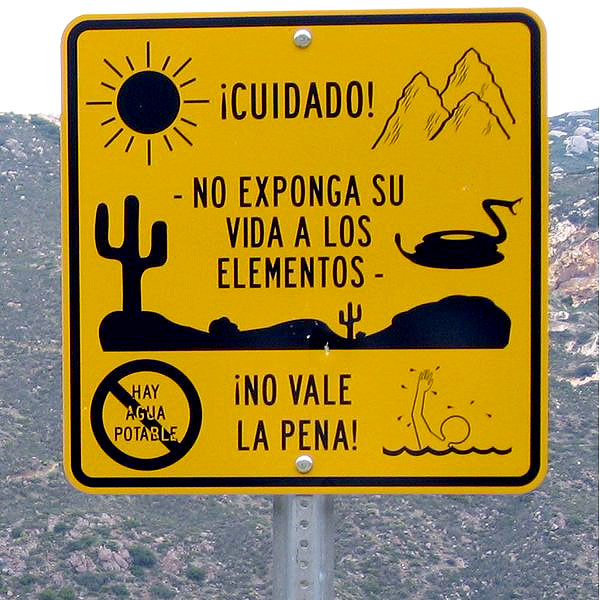

Another action taken by the U.S. government to stem the flow of migration has been the building of walls. For years they have existed only in urban regions (between Nogales-Arizona, and Nogales-Sonora, or between San Diego, California, and Tijuana in Baja California). It was thought that migrants would be deterred if they were only able to cross in the most difficult, arid and sparsely populated zones. However, the number of deaths in crossing the desert has grown exponentially (see graph). In 2006, the construction of a new wall was approved, which will stretch 1,100 Km and cost $49,000 million. Named by some “the wall of shame”, in reference to the Berlin Wall, it has been condemned by human rights organizations, ecologists, and the Mexican government.

Migration laws always respond to complex interests because the U.S. economy depends to a large extent on the cheap labour provided by illegal immigrants. The first U.S. migration law dates from 1790, and allows the naturalization of white people who have been in the country for more than two years. It wasn’t until 1952 that race distinctions were eliminated in migration laws. In 2004, President Bush proposed a reform that would allow migrants to work legally on a temporary basis, and return to their countries on completion of contract (inspired by the Bracero program), thereby stemming illegal immigration, together with measures that would strengthen border security. The reform finally approved in 2006 foresees the construction of the new wall, and makes it a serious offence, punishable with imprisonment, to remain in the country as an illegal immigrant.

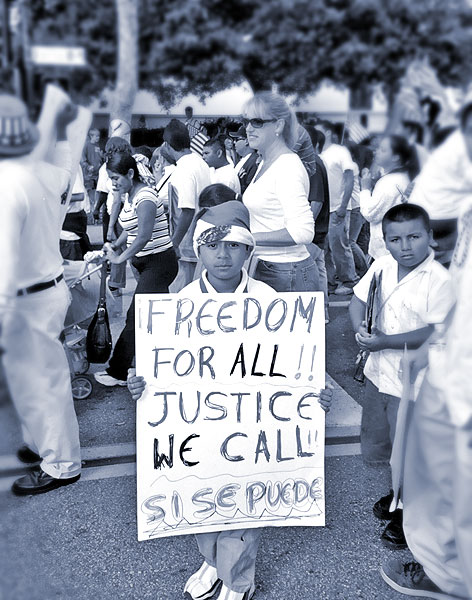

This law provoked the mobilization of millions of Latin Americans in the United States(3), including the strike on 1st May 2006, and made a reality of the fictional film by Sergio Arau, A Day Without a Mexican. It is impossible to ignore the economic, political and social implications of the presence of 42 million Latin Americans in the United States, now the largest “minority” in the country (15% of the total population).

Greater vigilance on the border, a tightening of migration laws and the expulsion of illegal aliens has not put an end to migration, but has certainly made it more dangerous and expensive, due to the corruption involved. Migrants have to cross the border at increasingly difficult and dangerous points, such as the Río Bravo/Grande or the Arizona desert. Here is one example among thousands: “In Ciudad Juárez there are tunnels big enough to enter on a bicycle. But all of a sudden a tap is opened and water is released. It happened that they turned on the water when we were crossing, and we were swept into the river. There were four of us, and one died. He drowned in the river and we watched him drown…”(4). Extreme temperatures in the desert and the lack of water claim the lives of many others.

The growing phenomenon of Chiapan migration

Today, 165 Chiapans a day leave the state in search of a life on “the other side”. Migration has increased rapidly. Whilst the population of Chiapas numbers over 4 million, around 300,000 have left for the United States in the last 15 years (500,000 according to CIEPAC, Centre for Economic and Political Research for Community Action).(5)Money sent from the U.S. to Mexico from migrant workers has risen from $13.9 million in 2000 to almost $800 million in 2006.(6). The importance of these remittances are evident: in 2005 the income from remittances was twelve times that of corn production, four times that of coffee sales, ten times that of tourism, six times greater than public investment in drinking water systems, and 30 times the amount invested in electrification.

“But these remittances which increase year by year have come at a high cost. Since June 2005, an average of seven dead bodies a month have been sent back to Chiapas.”(7)

Historically, the greatest numbers of migrants in Chiapas have come from the coast, Socunusco and the Sierra, but lately they have been emigrating from all over the state. More and more indigenous people are leaving their homeland, no longer able to make a living from agriculture. In Las Margaritas, a town at the entrance to the rainforest, there are “travel agencies” with buses that take people directly to the border up north. These are called “Tijuaneros“, after the border town that straddles California and the north of Mexico.

Another growing phenomenon is that of internal migration – people who move to international tourist resorts in the Yucatan or Quintana Roo to work in construction or the hotel industry, to Mexico City or, especially from the North of Chiapas, to the more industrialized neighbouring state of Tabasco.

Wages earned in the city are not necessarily high (around 600 pesos, or $54 a week), taken into account the cost of living. “In the (rural) community you live off the land – you have food to eat and a place to live. In the city everything is bought, everything is paid for,” says a woman who has moved from Tila, in the northern region of Chiapas, to Tabasco to work. Historically, people have also migrated to find temporary jobs in the countryside, with harsh working conditions and low wages. This is still seen as viable for indigenous communities, whose economy is centered on production for their own consumption. Internal migration is often the first step before leaving for the United States.

The dramatic consequences of migration

Economically…

Although in the beginning remittances provide help and relief for families who have remained in the place of origin, they are neither a secure source of income, nor do they eradicate poverty or contribute to social development: “Until now these resources have not been wisely spent. Chiapan families don’t know how to invest the money, and use it as a palliative to get out of the immediate crisis, only to fall back into debt and the hope that the next 200 dollars will arrive.”(8).

Although in the beginning remittances provide help and relief for families who have remained in the place of origin, they are neither a secure source of income, nor do they eradicate poverty or contribute to social development: “Until now these resources have not been wisely spent. Chiapan families don’t know how to invest the money, and use it as a palliative to get out of the immediate crisis, only to fall back into debt and the hope that the next 200 dollars will arrive.”(8).

Another consequence is that in towns where people were previously level in their standard of living, those who receive remittances suddenly have the means to move to a better house, or to buy a car and other luxury items. This rise in consumption has inspired younger people to migrate.

Migrants are mostly men between the age of 15 and 40. They leave behind a “ghost town” populated by women, children and the elderly. In two communities in Chiapas an investigation was carried out that revealed the existence of 302 women living alone(9).18 Their husbands had left for the United States. Some still received money from their spouses. Others did not, since their husbands had formed new families in the States. Migration usually brings about the disintegration of the family. On occasions, although not always, it has enabled women to play a greater part in local government.

Migration also affects the organization of the community. In better-organized indigenous communities it is made clear that returned migrants have to be reintegrated, and they are offered community post so that they can remain within the collective. Not all accept.

Culturally…

These are probably the most visible consequences. In the town of San Juan Chamula (Altos region), for example, Californian style houses are going up alongside traditional dwellings made of wood and mud. Changes can be seen in costume, language, food, the use of drugs, and (especially in the south of the state) the growth of gangs known as the “Maras“.

In the countryside there is growing unrest in the community. Some are starting to find life there boring, with little fun to be had, and the diet monotonous (beans, tortillas and pozol, a drink made of corn – every day). There are even those who want to change their name from Xun to its English variant John.

Violence is even more prevalent in the border towns, as well as all kinds of illegal trafficking (drugs, arms and people, etc).

Mexico: the northern frontier of South America

Throughout Central America, migration has become the principal survival strategy for broad sectors of the population who wish to improve their living conditions or assure better opportunities for future generations. Several countries remain in a post-war state, even after signing national peace treaties in which the structural causes of conflict have not been resolved.(10)

A flow of Central American migrants headed for the United States continues to traverse Chiapas; but Chiapas also acts as a destination in itself, especially Soconusco, which attracts farm labourers, domestic servants, workers in the service industry, sex workers and underage migrants. These possibilities have been decreasing, and control over the southern border of Mexico has grown tighter.

For those heading north, Chiapas is just the first step. “I can tell you that it is much harder, much more difficult and dangerous to cross Mexico than to enter into the United States. It’s 5,000 km to cross Mexico from Chiapas to the northern border. Crossing Mexico without papers is a terrible undertaking,”says an ex-coyote (person who smuggles people over the border).(11)

According to CIEPAC, Mexico is currently applying a strategy created in the United States, of using the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Oaxaca, as a lid to detain and deport Central American migrants. But at the same time, through dealings with polleros or coyotes (people-smugglers), Mexican authorities receive generous “compensations” in return for allowing the flow of human traffic. In economic terms, people-trafficking is the second biggest illicit activity in Mexico after drug-trafficking.

For Central American migrants, the danger does not begin on the northern frontier of Mexico, but in the south. Here is one example, that of Alma, a Honduran migrant: “Every day, every night, tens of Central American migrants prowl the streets of Tapachula waiting for the train to leave. As the train, known as The Beast, begins to move, the migrants climb aboard with the hope of arriving at the northern border, after long days on a journey whose success depends on the routes, the operatives, and sheer luck. Because of fear or precaution, Alma’s group decided not to board at Tapachula. Always lying in wait for the train to pass, the 15 Hondurans travelled by night, dodging places where there were police or criminals. At the northern border, the desert ended the lives of many migrants. At the southern border, they were killed by people or by trains. Alma and the others arrived at a place just beyond Huixtla, one week after leaving Honduras. Here they met with the train again. The group started running to climb aboard…Alma stretched out her arms but never caught hold of the hard metal. That was when she says the train ‘pulled’ her. As she tells the story, Alma makes a gesture in the air to illustrate the force that tried to suck her in towards her death. She tells of how she jumped backwards, which may be why her right leg ‘only’ lost 10cm above the knee.The left disappeared almost completely.”(12)

Basic necessities: structural causes behind migration

Necesidades básicas: causas estructurales detrás de la migración

Although crossing the border is becoming increasingly difficult, many choose to risk their lives to work illegally, without rights, in another country. This is largely due to the lack of economic options in their home country or the collective perception of the countries in the North as the land of opportunity, wellbeing and opulence.

In the case of Mexico, the fall in the price of coffee in 1989 and the negative impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, between Mexico, the U.S. and Canada), especially in the countryside, has reduced work opportunities for millions of Mexicans. Between 2000 and 2005 alone, Mexico lost 900,000 jobs in agriculture and 700,000 in industry.(13)

Political, economic and social marginalization, and the unequal distribution of wealth within the country and at a global level (differences between North and South) affect Mexico, Central America and Latin America in equal measure. Added to this difficult situation is a series of natural disasters (mostly hurricanes and floods that have hit Mexico and Central America in the last few decades) which has caused migrants to leave their homeland.

Although Mexico and the United States – and in parallel the countries of Western Europe – have taken harsher physical and legal measures to reduce migration, they have been unable to stop it, but have only made the human consequences more drastic. If the structural causes of migration are not addressed, people will continue to migrate as the only option for survival.

-

Article Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. (Return…)

- See Human Rights Watch (Return…)

- Article at Wikipedia (Return…)

- See Indymedia Barcelona (Return…)

- The numbers vary because of the illegal asspect of a big part the migration. (Return…)

- Chiapas migrante, article in estesur.com (Return…)

- Chiapas migrante, article in estesur.com (Return…)

- Chiapas migrante, article in estesur.com (Return…)

- Chiapas migrante, article in estesur.com (Return…)

- PALMA, Silvia Irene. Migración en la época de post-conflicto: vulneración de derechos de las poblaciones excluidas e impactos sobre la participación política. Project Counselling Service. (Return…)

- Someone who smuggle people over the border. The name comes form the very high price they ask and poor reliability, often they abandon the migrants before they reach their destination. (Return…)

- Article Migrantes: ¿Héroes o amenaza? – Adital (Return…)

- Webpage Foreign Policy in Focus (Return…)