ANALYSIS: Mexico 2008, Turbulence on the horizon?

29/02/2008

ANALYSIS: Mexico – Increase in cost of living and poverty pose major concerns

29/08/2008The detonator: energy reform

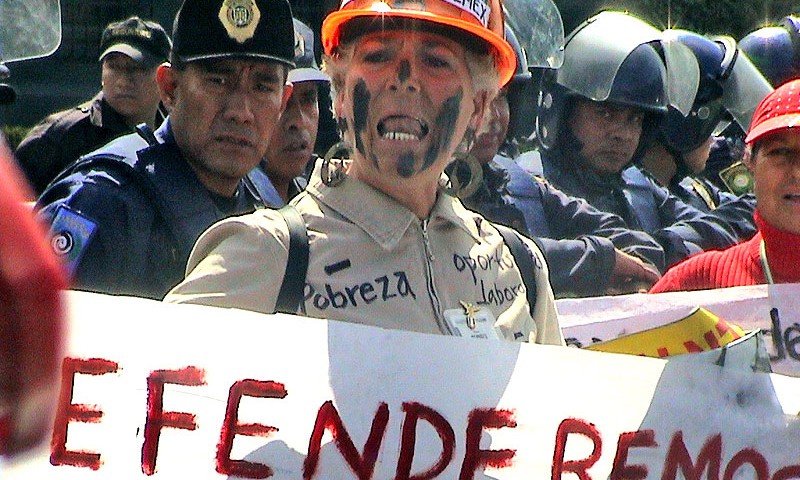

On April 9 President Felipe Calderón’s long-awaited plan for energy reform was finally presented to the Mexican Congress. This initiative aims to revitalize the oil industry, Mexico’s primary source of income, by authorizing greater resources to the state company Pemex, currently suffering a drop in production and lacking resources to explore new deposits. The reform would include modifications to more than a dozen laws, and introduces the concept of “extended services,” which would permit private participation at almost every stage of oil production (exploration, extraction, and refinery of oil and basic petrochemicals).

For some months, the National Democratic Congress (CND, Congreso Nacional Democrático) had announced that it would undertake actions of peaceful civil resistance to avoid what they consider an attempt to privatize the national oil company. The CND is led by former presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and the Broad Progressive Front (FAP, Frente Amplio Progresista); the latter is a coalition of the country’s principal left-wing parties, the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD, Partido de la Revolución Democrática), the Labor Party (PT, Partido del Trabajo) and Convergence (Convergencia).

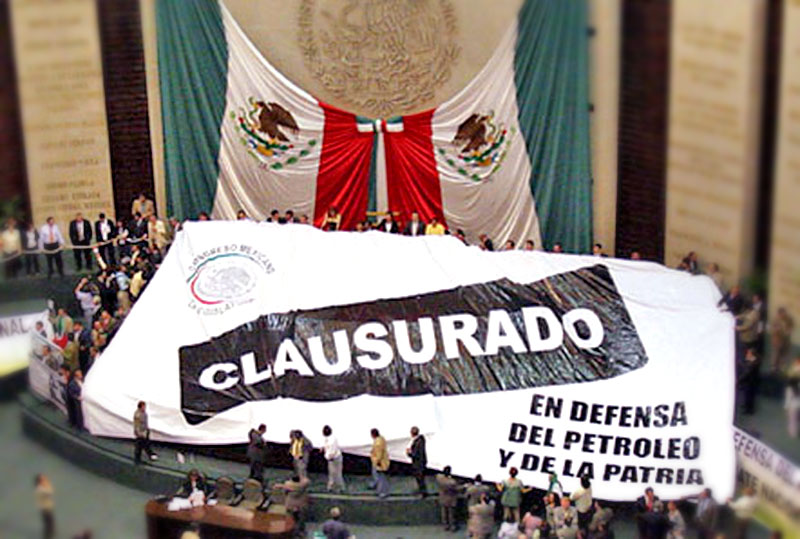

The first act of civil resistance occurred in the Senate on April 10, when the majority of the FAP’s legislators – in a surprise move – took control of the Senate chambers to demand a genuine debate on the future of the oil company. In the streets, thousands of women united in “brigades of peaceful resistance” and representatives of the Oil Defense Movement surrounded the chambers. From that date onward, the nation’s legislators have met in alternative locations, around which FAP supporters maintain protests. For the first time, mobilizations also occurred in other Mexican states.

The current polarization, present since the 2006 presidential elections, is not only reflected within the Congress or between the left and the right; it is also evidenced in the heart of the PRD itself. On March 16 elections were held to determine which of two candidates would be the party’s national president. Each candidate represented a strong political line within the PRD: Alejandro Encinas, closely aligned with AMLO, and Jesús Ortega, representing the so-called New Left. Numerous irregularities were reported in the election process, and at the time of writing the results have yet to be released. The two sides seem irreconcilable, as evidenced by the candidates’ differing responses to the energy reform.

Another facet of social discontent: NAFTA’s agricultural chapter

On January 31, a major protest was conducted to demand the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). It is worth recalling that on January 1, 2008, the agricultural chapter of the treaty came into effect, removing tariffs on basic grains such as beans and corn, as well as milk and oil-based products. During the event, which was considered the largest protest held in Mexico against NAFTA, the protesters denounced the initiation of the agricultural chapter as the “coup de grâce” for the Mexican farmer, and warned that if the chapter were not renegotiated there was an imminent risk of a “social uprising.”

In February, some 40 campesino, union and civil society organizations signed the Agreement for Food and Energy Sovereignty, Workers’ Rights and Democratic Freedoms, in which they ratified their unity as sole negotiator with the State. The attempt at dialogue between the federal government and the social organizations ended in March. In a joint communiqué, the organizations of the National Movement associated with the agreement stated that the Calderón Administration only sought dialogue with “like-minded or friendly organizations, in order to coordinate public policy, programs and rural budgets with an eye to the 2009 intermediate elections.” They affirmed that the government had frozen dialogue as “a strategy to weaken the movement.”

In March, the campaign “Without Corn There Is No Country” delivered to the Senate a letter with 438,000 signatures of citizens who support the exclusion of corn and beans from NAFTA. In addition, the signatories urged for the establishment of a permanent mechanism to administrate the import and export of grains, and the prohibition against planting transgenic crops.

Another source of dispute: penal reform

In February, Amnesty International reported that several of the proposals approved by the Senate in the matter of penal justice contain “elements that undermine progress achieved in terms of human rights and guarantees, and these areas therefore need to be reviewed and corrected before the bill is approved”. At the same time, the organizations of the National Front Against Repression (FNCR, Frente Nacional Contra la Represión) developed a plan of protests in an attempt to suspend the legislative process of the reform.

The reform has also been questioned by numerous national and international human rights organizations, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH, Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos) and the ombudsman of the 32 states of Mexico, who coincide in their opinion that the reforms “constitute a step backwards in regards to basic guarantees.”

Towards the end of February, the Commission of Deputies eliminated from the draft bill one of the most questioned proposals, which would have granted the right to search residences without a warrant. However, it has been denounced that the law maintains certain problematic structures, such as arraigo [administrative pre-trial detention]. It is worth noting that the law includes some improvements, such as oral trials and the change from an inquisitory system to an accusatory one (which includes the presumption of innocence). In March, the Senate approved the constitutional reform with the deputies’ modification mentioned above.

Sustained militarization and new denouncements

Denouncements of militarization across Mexico continue to multiply, with the most recent coming from the states of Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Sinaloa and Chihuahua. In the case of Michoacán, the State Human Rights Commission (CEDH, Comisión Estatal de Derechos Humanos) reported that since the beginning of 2008 it had received 56 complaints, accusing the Mexican army and police forces of “systematically” committing acts of personal violence, pillage and devastation. In Sinaloa at the end of March, the Military Prosecutor was involved in the investigation of 16 soldiers involved in the homicide of four youths in the municipality of Badiraguato.

“Joint Operation Chihuahua,” initiated on March 28, has dispatched approximately 2,500 soldiers and 500 federal agents and Public Ministry personnel to confront a wave of violence, which so far this year has resulted in 231 homicides. The Security Cabinet affirms that within a week of the start of the operation, almost 100 weapons and two tons of drugs had been decommissioned. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office announced that it had began an investigation into the incidents which had occurred in the operative, where it had found arbitrary detention, cruel and inhumane treatment, as well as cases of prisoners being held incomunicado and the prevention of visitors from the CNDH from entering military installations.

The Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA, Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional) warned that members of the Juárez Cartel, whose activities are focused in the state of Chihuahua, plan to conduct “tumultuous” human rights violations by dressing as soldiers and conducting supposed home searches, an action which would undermine the prestige of the Armed Forces. According to SEDENA, “As part of this strategy, the aforementioned organization has been sponsoring marches, sit-ins and pronouncements without any legitimate basis.”

Army on the streets until at least 2012

In January, the president of the CNDH José Luis Soberanes met with the new Government Secretary, Juan Camilo Mouriño, to request that the army cease carrying out tasks appropriate for the police force. He insisted that according to national law, the functions served by the armed forces were clearly outlined, as were those to be performed by public security forces.

In February, human rights organizations warned that army participation in security maneuvers was an example of serious deficiencies in regard to respect for individual guarantees. An example of this is the installation of military checkpoints in various locations across the country. Adrían Ramírez, director of the Mexican League for the Defense of Human Rights (LIMEDDH, Liga Mexicana para los Derechos Humanos) considers that the first step to complying with these recommendations should be the suspension of all public security activities: “They are trained to attack the enemy, and here that isn’t the case. Another step would be to make the process of seeking justice more transparent for the relatives of victims [of army actions].” For several human rights organizations, the creation of the General Directorate of Human Rights is insufficient, as the directorate does not have a mandate allowing it to protect individual guarantees due to the discretional nature of war-related information.

In April, the National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” and the Human Rights Center “Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez” reported that with the involvement of the army in public security maneuvers, there has not only been an increase in the human rights violations of the civilian population, but “neither have they achieved greater effectiveness in combating problems caused by drug trafficking.” Since January, however, President Felipe Calderón ordered that the army remain on the streets until at least 2012 in order to continue the task of combating organized crime and drug trafficking.

… … … … … …

Human rights briefs

OHCHR Visit

In early February, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, paid a visit to Mexico. Civil organizations meeting with Arbour presented her with a report on the human rights situation in Mexico noting that, “The document establishes that though the alternating governments in Mexico have advanced formal democracy, they have not brought about substantial change to the human rights situation in the country. The steps taken in terms of human rights have been more for show than anything else.”

At several points the High Commissioner expressed her concern with the insignificant advances made in the investigations of the femicide that continues to occur in Juarez, Chihuahua, as well as the cases of more than 500 disappeared as a result of the dirty war and the criminalization of social protest. She also warned that the army’s participation in policy making is not appropriate in the long run and could even prove dangerous. She also stated that “if the Mexican Army carries out civil or police functions, it should be held accountable to a civil authority.”

CNDH: Questions and Reforms

In February, Human Rights Watch (HRW) confirmed that the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) continues to revert to a particular “legal principle which completely distorts and they use it to protect government officials who abuse their authority instead of protecting the victims. In addition, it (the CNDH) has demonstrated a profound indifference towards the international norms it is supposed to be upholding and has acted with diffidence in the Televisa and military jurisdiction cases.” The president of the CNDH refuted the report and argued that it contains inaccurate facts that do not correspond with the reality of the situation.

Similarly, the Congress has discussed a constitutional reform with regard to social guarantees that would have a structural impact not only at the CNDH but within local human right commissions as well. In April, the Congress approved a proposal that excluded several of the initial proposals. Of the 93 proposals set forth, six reforms were decided upon: the securing of the independence of local human right commissions, a constitutional right to life without violence, political jurisdiction and discretion in the hands of the president of the CNDH, respect for human rights within the penitentiary system and the right to education for women.

Atenco

In January, fifteen of the twenty-one law enforcement officials under criminal trial for abuses committed during the police raid at San Salvador Atenco in 2006 were cleared of the charge of abuse of authority, after receiving a federal injunction for the poor integration of the proceedings which the Attorney General of the State of Mexico brought against them.

However, in March the Investigatory Commission of the National Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN, Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación) concluded the first phase of its investigation of the events that took place in Atenco in 2006 and acknowledged the occurrence of “possible serious violations” of individuals’ rights and the coordination of police orders “of a higher level” in the planning of the operation that ended with the deaths of two people and the arrest of some 207 others, of which “only nine left unscathed.” The authorities that are mentioned as having been involved will be notified so that they may present their case. Having completed that step, in a full court session, a resolution will be presented (without any judicial consequences).

… … … … … …

Chiapas: continued alarm

In April, the Secretary of the Interior decided to put an end to the Coordination for Dialogue and Negotiation in Chiapas created in 1994 after the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) uprising. The decision was made due to the Coordination’s supposed austere nature and lack of necessity. The group Peace with Democracy (Paz con Democracia, consisting of various Mexican personalities and intellectuals) said in February that if a return to the negotiating table (suspended in 1995) is improbable, there would be a “new escalation in the war in Chiapas.” A few days prior, before the intensification of aggressions “towards peoples, nations and tribes,” the National Indigenous Congress (CNI, Congreso Nacional Indígena) had also declared itself in opposition to the hostilities towards Zapatista communities in Chiapas “that in recent months has intensified due to paramilitary organizations such as the Organization for the Defense of Indigenous and Campesino Rights (OPDDIC, Organización para la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas y Campesinos).”

The aggressions and threats of forced eviction have been made in various ejidos, communities and municipalities including Ch’oles de Tumbalá, Huitepec, Bolom Ajaw, Chilón and Agua Azul among others. Peace and Democracy denounced “The episodes of robbery, the burning of houses, deaths, death threats, property evictions, one after another. They are trying to strip the rebel communities of their lands and territories.”

In addition, there are contradictory statements being made at different levels of government. While some mayors have announced the forced eviction of Zapatista communities and territories, the state government has called on the municipal presidents to respect “all expressions” and act through dialogue and tolerance “whatever the situation presented in the municipalities is.” The state has also made clear its intention to dismantle the OPDDIC. In April, more than one thousand campesinos from the ejido Nazareth in the municipality of Ocosingo, reiterated their resignation and total departure from the paramilitary organization.

In a more general sense, in February, the Internacional Civil Commission for Human Rights Observation (CCIODH, Comisión Civil Internacional de Observación de Derechos Humanos) pointed out that throughout the current administration in Chiapas “the police agencies still proceed with the arrest of innocent people as a result of false criminal reporting, in collaboration with paramilitary groups; they make charges based on events that never happened; they instigate self-incrimination through torture and then process individuals on that basis. All of this is taking place within criminal trials that are replete with irregularities.”

… … … … … …

IMMIGRATION: Failed subject at the northern and southern borders

Social organizations and federal legislators have stated that the persecution, harassment and human rights violations of Mexican immigrants have increased at the border with the United States. In addition, the strengthening of the immigration policies in the US has made the situation even harder for Mexican migrants along with the effects of the recession, continuing xenophobia and the strengthening of laws that require whole families to return to Mexico. In 2007 513,014 Mexicans were deported, more than 400 each day.

In late February, the proposition Zero Tolerance also known as “Do Not Pass” was put into effect in El Paso, Texas. The measure will initiate legal actions against those immigrants that repeatedly attempt to cross the border illegally. Those who are caught in subsequent attempts will be imprisoned for up to five years and fined up to $500 USD. In addition to the opposition heard from civil groups, in March, the representative from the Organization of American States in Mexico, Oscar Maúrtua de Romaña, criticized the program.

In March, The Special Rapporteur to the United Nations for the Rights of Immigrants, Jorge Bustamante, paid a working visit to Mexico. In ending his trip he stated that the human rights of immigrants are violated at a higher proportion in Mexico than those suffered by Mexican immigrants in the United States.