SIPAZ Activities (May – August 2003)

29/08/20032003

31/12/2003“We will be compatriots and contemporaries of everyone who has a will to justice and a will to beauty, having been born where they were born, having lived where they have lived, without caring about maps or times.”

El Derecho al Delirio. Eduardo Galeano

January of 2004 completes ten years since the armed uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). A decade in which the communiqués, consultations, marches, forums and meetings have created a new ethico-political thinking that has had a profound influence, not just in Mexico, but also at an international level.

We should like to take advantage of this event to reflect on the process that has developed since ’94, and to look at the fruits that the dialogue between this socio-political movement and national and international civil society has given birth.

Neo-Zapatismo: New political ethic

The political discourse of the EZLN, accompanied by poetry, stories, irony and reality, surprised a national and international political scene in a culture of hopelessness and dejection.

In their communiqués the Zapatistas fuse distinct Mexican cultural roots with those of the world. They demand a society in which democracy, liberty, and justice prevail, founded in human dignity. These terms, considered by them to be “the first of all words and all of the languages,” are redefined in light of their own cosmic vision:

“justice is not to punish, it is to recover for each one what they deserve and each one deserves what the mirror returns: himself. That which gave death, misery, exploitation, elitism, arrogance, has as its just deserts a good amount of pain and suffering in its path. That which gave work, life, struggle, that which was a brother, has as its recognition a little light that always illuminates his face, chest and walk.

liberty is not that everyone does what they want, it is the ability to choose whatever path you’d like, to encounter the mirror, to walk the true word. But whichever path, do not lose the mirror. That you don’t come to betray yourself, or yours, or others.

democracy is that thinking which leads to a good agreement.. Not that everyone thinks the same(…). That the word of rule obeys the word of the majority, that the staff of command has the collective word and not only the will of one. That the space reflects all, walkers and path, and would be, as such, a motive for thinking inside oneself as well as thinking on the outside world.”

(La historia de las palabras. El Viejo Antonio)

The French sociologist Yvon Le Bot speaks of the “Zapatista dream”. The researcher Guillermo Michel, speaks of “Zapatista Utopia”, reclaiming the definition of Paulo Freire, for whom the utopia is “the act of denouncing the dehumanizing structure and announcing the humanizing structure. ” (MICHEL, 2001:122). They explain that the Zapatistas from the south of the south are converting themselves into a voice of denunciation and a mirror of the injustices that people were suffering in Chiapas and other parts of the planet. At the same time, they announced that what they want is “another possible world”: “In our dreams we have seen another world. A true world, a world that is definitively more just than the one in which we are now walking. We saw that in this world the army was not needed, that in it there was peace, justice and liberty so common that they weren’t spoken of as something far away, but rather in the way you speak of bread, birds, air, water, the way one says book and voice. (…) And in this world it was reason and the will of the most governed, and those that ruled were people of good thinking; they ruled by obeying, this true world was not a dream of the past, nor was it something that came from our ancestors. It was from ahead that it came, it was from the next phase that we’re giving. It was in this dream that we began to go towards achieving that this dream would sit at our table, illuminate our house, grow in our fields, fill the hearts of our children, clean our sweat, heal our history, and for everyone it would go.”

Democracy, understood as consensus and collective participation, is demanded and expressed in the principle “rule by obeying”: “It is the reason and will of the good men and women to seek and find the best way of governing and self governing, the one which is good for the most people, which for everyone is good. But that does not silence the voices of the few, rather that they continue in their place, waiting that the thought and heart are joined in what is the will of most people and the opinion of the few.” (Communiqué, 27th of February, 1994).

The novelty of the scope of the fundamental human rights lies in demanding the right of the participation of everyone, honoring the right to the differences which are already there, in ethnic character, sexual preference, social class, age, or gender. The Zapatistas defend a world in which many worlds fit. In the first communiqués they recognized the different struggles which are taking place in all of Mexico, and launched a proposal, “We want that the footprints of everyone who walks in the truth, that they unite in one footprint.” (Communiqué 27 from January 25, 1994).

Drawing paths in between dreams and words

Since the Zapatista uprising, national and international civil society converted itself into the main interlocutor of the EZLN. We should remember that the ceasefire declared by the Federal Government in 1994 was in a large part due to the multitudes of people that gathered to protest in Mexico and other cities of the world.

In Mexico, civil society sprung forth from the seismic catastrophes of 1985, and later in opposition to the electoral fraud of 1988. It represented a plural collective, different from the political parties and the government, desiring a true democratization of the Mexican nation in which it was playing the role of protagonist.

The epistolary relationship during the first year of the uprising is ample: “The EZLN is accustomed to releasing communiqués to establish its positions on different points. We do it this way so that the Mexican public, which is now called civil society, knows our thoughts directly from our heart.” (Communiqué, May 5th, 1994).

In these letters, the Zapatistas begin to trace the kind of solidarity that they want to establish with the non-governmental organizations (NGOs), labor unions, women, students, independent indigenous and campesino organizations, etc. We encounter this theme in the letter of response to the students of the UNAM offering this advice: “We don’t want you to come to push on us some political current. (…) You can come to teach us and to learn.” (Communiqué, February 12th, 1994).

The first dialogue between national civil society and the EZLN took place at the National Democratic Convention (1994). To hold this dialogue they constructed the first Zapatista Aguascalientes in La Realidad. It was conceived as a meeting site between national and international civil society and the Zapatistas. Later they formed four more Aguascalientes: La Garrucha, Oventik, Morelia, and Roberto Barrios.

In 1994 Amado Avendaño was named governor of civil society “in rebellion” and stayed in the position until the year 2000. In 1995, the EZLN held the National and International Consultation for Peace. More than a million people responded, demonstrating a preoccupation of public opinion with Chiapas, and pronouncing themselves in favor of the EZLN transforming itself into a peaceful and independent political force. And in fact, that was what modified the Zapatista political strategy.

In 1995, the San Andrés dialogues began between the Federal Government and the Zapatistas, where part of civil society participated as advisors to the EZLN, and also formed security cordons to safeguard the participants. The Zapatista proposals that brought about the San Andrés Accords (ASA) on Indigenous Rights and Culture reclaimed the consensus of the National Indigenous Forum. In this forum it was decided to form the National Indigenous Congress, which today continues to unite a large part of the indigenous communities in Mexico. The Forum on the Reform of the State (1996) pursued accords between the EZLN and national civil society with the goal of presenting them in the Second Round Table on Democracy and Justice.

In the Forth Declaration of the Lacondon Jungle, they called on civil society to form the Zapatista Front for National Liberation with the objective of continuing the political fight through the formation of an independent political force.

With the San Andrés Dialogue interrupted since the end of 1996, they undertook the March of 1,111 (Zapatistas) to attend the Second Assembly of the CNI in Mexico and to demand the fulfillment of the ASA. In preparation for the Consultation on the Recognition of the Indigenous Rights and Culture and for the End of the War (1999) they held the Meeting EZLN-civil society in San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

The arrival of a new president through elections in 2000 was conducive to what had been promoted as the last mobilization and meeting with national civil society outside of Zapatista territory: “The March of the Color of the Earth.” The Zapatista commanders and Subcommandante Marcos undertook this journey to visit different Mexican states in order to explain the reasons why they demanded that the government approve what is called the COCOPA law (a proposed constitutional reform for indigenous and cultural rights which recognizes the main agreements of the ASA) as a condition for the renewal of the dialogue.

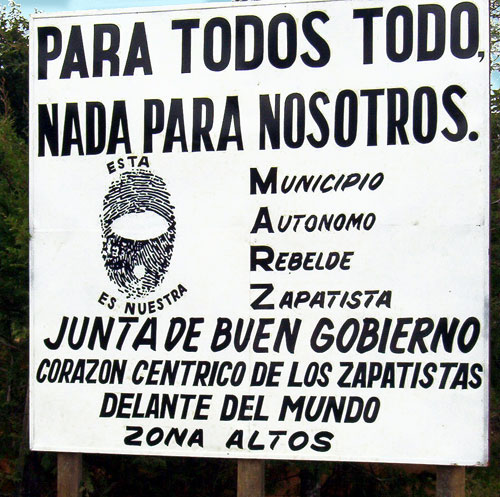

Last August, the Autonomous Zapatista Municipalities invited all of international and national civil society to the death of the “Aguascalientes” and the birth of the “Caracoles“, with the intention of improving relationships with national and international civil society.

From the local to the global: a journey coming and going

The bridge laid out between civil society and the EZLN has a double lane where there circulates the proposals and responses in a journey of coming and going.

Over the Internet, links began to be created between the neo-Zapatista struggle and the collectives and individuals who were reading proposals from all over the world. The expressions of solidarity from outside Mexico followed the uprising, with demonstrations on the 14th of January in Madrid and Paris respectively.

Later, international civil society was called to participate in the First Meeting for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism (4th-8th, April 1996), which prepared the way for the later First Intercontinental Meeting for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism from the 26th of July to the 8th of August 1996 (also known as “Intergalactic“).

From these discussions was proposed among other things the creation of a network from the bottom up: local, state, national and international, and the construction of bodies or nodes of this network that function through consensus and rule by obeying. The economic standard was set for constructing an economic alternative, starting from the recovery of basic principles such as dignity, solidarity, self-rule, diversity and cooperation based on the needs of real humans. Also it was decided to link the struggles for democracy and the rights of citizens of the so-called first world with the struggles for autonomy by indigenous peoples.

Many proposals were adapted and continued through international civil society. In this way the First Continental Meeting for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism had a second session in Brazil, and the Second Intercontinental Meeting was celebrated in July of 1997 in Spain.

But beyond the isolated meetings and forums there began to form a permanent network of collectives in solidarity with the Zapatista struggle, through the so called Support Platform or Zapatista Solidarity, and by means of unions with autonomous Zapatista municipalities. Last year in Madrid they announced the construction of a permanent Auguascaliente similar to those already existing in Zapatista territories, to create a place of meeting and encounter between whoever wanted to construct another type of politics in that society.

The co-habitation of international observers during weeks and months in civil observation camps located in different autonomous municipalities has permitted the establishment of true intercultural exchange. It is no surprise, then, that in the statement “Chiapas the thirteenth stele” it was consistently recognized that all the building until the present moment hasn’t been the fruit only of the Zapatista supporters but also of national and international civil society.

The globalization of hope

For three years now, people have been holding the Social Forum at Porto Alegre as a space in which to construct an alternative economy, politics, society and culture that permits the inclusion of the millions of marginalized people who exist in the world for different reasons.

From Seattle, Washington, Davos, Melbourne, Quito, Belem do Para, Rome, Venice, Prague, Istanbul, Porto Alegre, Cancun, Quebec and Geneva, the Zapatistas announce… “…We are the same as you (…) Behind our black masks is the face of all the excluded women; of all the forgotten indigenous; of all the persecuted homosexuals; of all the disappeared youth; of all the beaten-down migrants; of all those dead from being forgotten; all the men and women, simple and ordinary, who do not count, who are not seen, who are not named, who do not have a tomorrow.” (Communicated by Comandante Mayor Ana Maria, 27th of July 1996).

There are those who consider the resistance of globalization on a world scale to have been inaugurated in the protest against the ministerial meeting of the World Trade Organization in Seattle in 1999. However, the reporter Naomi Klein (author of “No Logo”) goes further back and points out that the beginning of anti-globalization struggle or “altermundialista” (a Spanish language term for anti-globalization activism suggesting that another world (alter mundo) is possible) can be seen on the first of January 1994, with the Zapatista uprising (La Jornada, 18th of May 2000). This view corresponds with that of Ignacio Ramonet, for whom the Zapatista rebellion constituted the first insurrection against globalization (RAMONET, 2001: 24). In this same sense Gonzalez Casanova affirmed at the second Social Forum at Port Alegre that the protests at Seattle would have been unthinkable without the armed uprising of 1994. The coincidence of the armed rebellion with the forceful entrance of the North American Free Trade Agreement reflected the nonconformity with a politics that forced out the participation and the interests of indigenous people, which would prejudicially influence the prices of the rural areas, and increase the impoverishment of the peasants unable to compete with the prices of North American farmers.

Subcomandante Marcos affirmed recently: “we do not think that [the anti-globalization movement] is a linear movement, with antecedents and consistencies, nor that it must be seen through a geographical situation or calendar, to say that it was first in Chiapas, then Seattle, and after Genoa and now Cancun” (Muñoz Ramirez, 2003: 287). He defined neo-Zapatismo as “the symptom of something more that is going on in South America, in North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Oceania (…) a symptom of the pockets that have been isolated and forgotten and are fighting to open up, to break and to try to meet one another, to finish with this world of the Stock Exchange (literally “pockets of value” in Spanish) the pockets of others, and the pockets of oblivion.” (“Some words about our thinking”)

What is certain is that the “altermundialista” movement has consolidated and developed progressively, moving from being an anti-establishment movement to also being intentionally constructive. It has as its principle features plurality and heterogeneity, defending politics constructed “from below,” combining transgression and direct confrontation with a will to participatory action. It represents the defense of the universalization of human rights, going beyond the sovereignty of nations, but also apart from the institutions created by those same representative bodies of the state.

For the necessary construction of a positive peace in Chiapas, SIPAZ is based on the conviction of the recognition of the value of all, and the recognition that the same one who is dividing also belongs to a united humanity. We represent a bridge which permits a trip from the local to the global, shedding light on the conflict in Chiapas for the outside world, but also from the global to the local, through our presence which represents myriads of organizations and people from other places on the planet who want to continue to be present in this territory, showing their concern for the permanence of a conflict which continues without resolve.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- La Jornada, Chiapas: el alzamiento, México, La Jornada, 1994

- Ramonet Ignacio, Marcos, La dignidad rebelde, Valencia, Cybermonde, 2001

- Le Bot, Yvon, El sueño zapatista, Barcelona, Anagrama, 1997

- Subcomandante Marcos, Relatos del Viejo Antonio, México, Centro de Información y Análisis de Chiapas, 1998

- Michel Guillermo, “Votán Zapata. Filísofo de la esperanza, México, Rizoma, 2001

- Muñoz Ramírez, 20 y 10, El fuego y la palabra, México, La Jornada, 2003

- EZLN, Documentos y Comunicados, Ediciones Era, 1997