SIPAZ Activities (Mid-April to end of July 2008)

29/08/2008

ANALYSIS : Mexico, A Bleak Picture

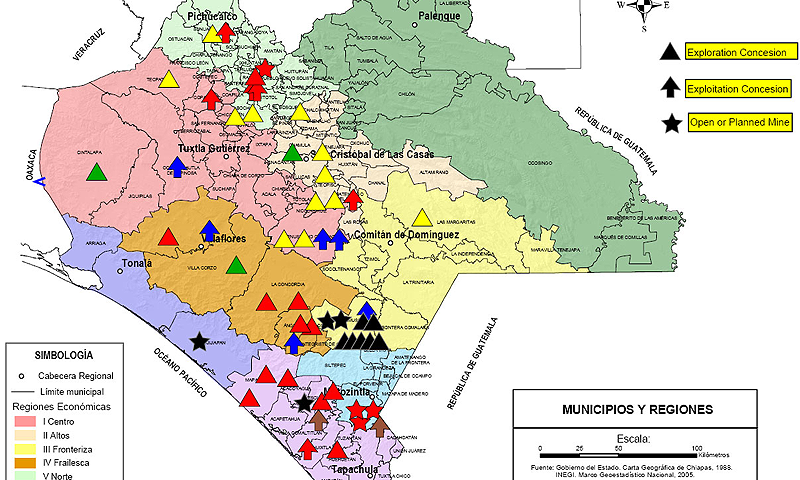

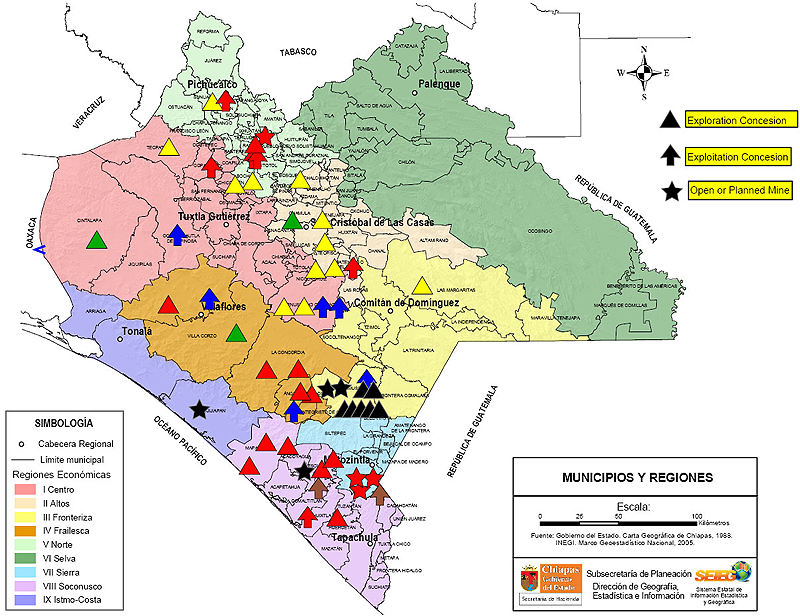

30/12/2008Until recently the state of Chiapas, which is one of the richest in Mexico in terms of natural resources (in 2001 it produced 47% of natural gas and 21% of oil in Mexico(1)), seemed to have been forgotten by the mining industry. However since the late 1990’s, the Federal government began to grant mining concessions for exploration and exploitation to transnational mining corporations, for the most part based in Canada.(2)

The majority of these concessions are located in the Sierra Madre del Sur mountain range which begins in the north of Chiapas and extends as far as Honduras and into northern Nicaragua, regions in which these same mining companies are already working.(3)

The Mining Reforms: Paving the Way for Transnational Corporations

One of the major precursors to the increase in mining concessions was the constitutional reforms of 1993. These reforms, which played a part in paving the way for NAFTA(4) allowed foreign corporations to hold mining concessions, which previously had been reserved for Mexican companies. Beginning with the Mineral Law of 1993 and throughout the nineties, a number of new mineral reforms were passed which facilitated mineral exploitation by foreign capital.(5)

Traditionally, the Mexican people had the right to the land, through ejidal(6) and communal lands, while the state had the rights to anything below the soil. This ambiguity in jurisdiction between the surface and the natural resources beneath allowed the affected communities or ejidos a certain amount of bargaining power when their land was affected by mining interests. However after the mineral reforms of the nineties this issue was resolved in favor of private interests. They state that the concession grants the right to “Obtain the expropriation, temporary occupancy or creation of land easement needed to carry out the exploration, exploitation and beneficiation works”(7). This effectively grants mining companies the priority to the land over the people who are living on it. In addition the new laws give the company water rights in the regions they are in as well as the right to dump rock waste in addition to other waste products.

As the changes to the mining laws were aimed at facilitating the entrance of foreign capital into Mexico, essentially the reforms deregulated the mining industry in Mexico(8). This is part of the neoliberal economic doctrine which claims that growth and development will be stimulated by deregulating the economy and allowing the unhindered movement of international capital.

NAFTA was heralded by businessmen and politicians throughout the US, Mexico, and Canada as an agreement that would bring prosperity and development. However the reality has been that since this agreement the Mexican economy has seen a loss of jobs and food prices have risen. The rural campesino population has been the most adversely affected by the agreement. The end result has been that large corporations have benefited while poverty in the country has grown.(9)

International Capital: Exploiting the Mineral Wealth of the SierraCanadian mining companies are known for their exploits in Central America and due to the fact that the mining industry requires an incredible amount of equipment and money, the vast majority of mining concessions in Mexico have been given to these large Canadian mining corporations. While these corporations are based in Canada, they have operations throughout Central and South America. The concessions are owned by Mexican subsidiary companies who are in turn owned by the transnational corporations. These subsidiary companies physically run mining operations but are completely owned and directed by corporations based in Canada. This is done for a number of reasons, but chiefly because by maintaining distance from the on-the-ground operations the companies can create a barrier between themselves and any environmental or social damage that results from the mining. In addition there is generally less opposition within communities if the communities believe that the company is Mexican. In the state of Chiapas there are six major international mining companies operating in different stages of the mining process. There are two companies that maintain open and functioning mines and the rest are still in the exploration or construction phase. These companies are mainly mining gold and silver but are also extracting barite, titanium, magnetite (iron ore), and copper.(10) One of the main companies in Chiapas is Blackfire Exploration Ltd., which is based out of Alberta, Canada and totes the slogan “Aggressively Exploring and Developing Chiapas, Mexico”. This company, through a number of subsidiaries and front companies, has acquired 27,412 hectares for exploration and exploitation. They have one open barite mine in the municipality of Chicomuselo as well as two more mines planned for 2010 in the Sierra region.(11) Another company, Linear Gold Corp., through two different front companies owns 198,416 hectares of exploration rights and is currently operating an open gold mine in the municipality of Ixuatán in the north of Chiapas. In addition Linear Gold has a number of projects through which it is exploring a possible gold mine in the municipality of Motozintla.(12) The remaining four companies (3 Canadian and 1 Chilean) have not yet begun open mining operations but have concessions for exploration and in some cases exploitation as well. These companies are Radius Gold Corp. which has 103,210 hectares, Fronteer Development Group which has 208,392 hectares, New Gold Inc. which has 246,249 hectares, and CODELCO, the Chilean national copper mining company which has 121,831 hectares. These companies have concessions throughout 31 different municipalities in the state of Chiapas, however most of them lie in the southern Sierra region of the state.(13) |

The Environmental and Social Effects of Modern Mining Practices

While the industry has undergone many changes mining remains one of the most detrimental, not only in terms of working conditions but in regards to environmental and social damage. According to Gustavo Castro of Otros Mundos Chiapas A.C. “Mining is not new in Chiapas, what is new is the intensity and the type of extraction”(14). Modern mining practices continue to have a negative impact specifically in terms of land and water contamination, deforestation, destruction of traditional lifestyles, and internal divisions within communities.(15)

The most common modern mining practice is called opencast mining. According to a report published by the World Rainforest Movement, an international network of organizations that work on issues of rainforest conservation:

Opencast mines look like a series of terraces arranged in great deep wide pits in the middle of a desolated and stark landscape, lacking any living resources. The operation usually starts with removal of the vegetation and the soil, followed by extensive dynamiting and removal of the rocks and materials above the ore until the deposit is reached, which is again dynamited to obtain smaller pieces(16).

In addition, once these giant heaps of rock and dirt are dug up the valuable minerals inside must be extracted. This is generally done by running the raw materials through a chemical solution in order to extract the minerals. In the case of gold mining, a cyanide solution is run over the ore in order to dissolve the rock and extract the pure gold. The mining companies claim that the cyanide and the leftover debris are disposed of in an environmentally conscious manner but it is inevitable that some of these damaging chemicals manage to escape into the soil and the water supply(17). This kind of pollution is especially harmful to campesinos; not only because of the health risks associated with contaminated water but because the pollution threatens their traditional lifestyle of subsistence agriculture.

Another major side effect of this cyanide leaching process is the rock waste that it produces. According to the ‘No Dirty Gold’ campaign started by Earthworks (an American NGO that works on environmental issues) and OxFam (an International NGO which works on a number of social and environmental issues) these piles of toxic slag can reach up to 100 meters high. These toxic piles of rock not only damage the soil through the leaching of chemicals but they also physically take up land that would otherwise be used for farming.(18)

The entrance of mining companies into the region has a number of negative effects on a community level. Generally the companies promise some sort of payment either in the form of cash payout or infrastructure in order to placate the affected communities. Nevertheless, there is no way to ensure that the companies carry out their promises. The reality is that the vulnerability and poverty of the affected communities do not allow for fair negotiations. The money that is offered may seem like a large amount to the families who do not know what the true effects of the mining operations will be.

For example in the municipality of Chicomuselo (Chiapas), the company Blackfire Exploration has an open barite mine called La Revancha (The Revenge). According to community members, when the company entered the area in 2006 it promised the community that it would build new roads, install electricity, drainage and other infrastructure in the community. The company has never actually followed through on the agreement. Instead of building roads, installing electricity, and sewage for the entire community, the company built roads, installed electricity, and other infrastructure for the mining operation alone without constructing anything of benefit for the community.(19)

Building a Resistance to International Mining

The resistance to the operation of mining in Chiapas and Mexico as a whole is growing but very slowly. One of the main problems in organizing such resistance is the lack of awareness in communities about what the effects of a mine are likely to be. The reality is that in many cases people only realize the effects of the mine after it is in place and functioning, and by that time it is generally too late to stop the mining process(20). The mining companies are also aware of the resistance and utilize strategies that attempt to halt it before it gets off the ground. These strategies include buying out part of the community in order to create divisions and stop any attempts at organizing. This is generally done by co-opting local authorities or community leaders with the intent of creating divisions and stifling any possible resistance.

One of the major methods utilized by communities to resist the entrance of mining corporations involves the use of a number of national and international accords that guarantee the economic, social, and cultural rights of individuals.

On a national level, the best defense for communities and ejidos affected by mining is the Agrarian Law and the rights that ejidos hold as communal bodies. The laws concerning ejidos grant the right to decide the use of the land as a communal body. However since the changes to Article 27 of the Constitution in 1992 and the implementation of PROCEDE(21) it has become very difficult to employ these defense mechanisms.

On the international level, one of the most important tools is the 169th Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, which was established by the International Labor Organization (ILO) and ratified in Mexico in 1990. It states in particular that “In cases in which the State retains the ownership of mineral or sub-surface resources or rights to other resources pertaining to lands, governments shall establish or maintain procedures through which they shall consult these peoples, … The peoples concerned shall wherever possible participate in the benefits of such activities, and shall receive fair compensation for any damages which they may sustain as a result of such activities” (art. 15)(22).

The 169th Convention has been successfully used by communities in Guatemala in resisting international mining interests. For example on February 13 of 2007, 64 communities in the municipality of Concepción Tutuapa rejected mining activity in their communities. Through the logic of the 169th convention, the people of the region voted in community consultations to reject the international mining companies.(23)

Nevertheless, even though Convention 169 guarantees the right of indigenous peoples to be consulted, it does not guarantee the right to veto a project. The reality is that while the state is required to inform the population and try to limit environmental and social damage, it does not necessarily mean that the project will be stopped.

Another major means of resistance is organization and mobilization on a community, national, or international level. Community level organization is important because it is one of the only methods of educating people about what the effects of mining will be as well as educating and mobilizing people around methods of resistance. One of the main actors in organizing resistance to mining is the Mexican Network of Those Affected by Mining (REMA, Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Minería). This is a national network that is attempting to organize and inform people throughout Mexico about the effects and methods of resistance to mining(24).

Another actor in the mining resistance at the local level is the National Front of Struggle for Socialism (FNLS, Frente Nacional de la Lucha por el Socialismo). In November, the FNLS held a statewide mobilization protesting a number of issues, among them that of the transnational mining companies. It included roadblocks on a number of highways in Chiapas as well as a march on the municipal seat of Motozintla where there have been a number of mining concessions to Linear Gold Corp(25). The FNLS has denounced repression against its attempts to organize resistance to the mining in the region. On November 12, 2008 they stated that “For the FNLS, the raids that were carried out yesterday on the houses of Yolanda Castro and Jaime González, represent a fascist response from the Mexican State to the public denunciation that we released on the 10th and to the Resistance against the removal of minerals being carried out by a number of transnational corporations”.(26)

Another example of community organization as well as government repression is the case of El Carrizalillo in the state of Guerrero. In January 2007, the community organized the “Permanent Assembly of Ejidatarios and Workers of Carrizalillo”. This group coordinated a roadblock at the entrance of a mine run by the Luismin company in order to pressure them into renegotiating the contracts for use of the land. However at the end of January, 100 state and local police officers violently removed the roadblock and arrested 70 community members. Eventually the company agreed to negotiate new contracts with the community. The final accords resulted in raising the rental price of the land from 1,475 pesos to 13,500 pesos per year per hectare. In addition the company promised the construction of a number of public works including roads, a hospital, and a school. The company also promised to re-employ the workers who had been fired during the 82 days of the strike.(27)

On November 8, 2008, the community of Cacahuatepec, Guerrero (that would be affected by the planned hydro-electric dam La Parota) held the popular gathering titled “Water, Energy, and Alternative Energy”. The theme of mining was touched on at the gathering and community members from Chicomuselo, Chiapas met with others from different parts of Mexico to share their experiences with mining, other natural resources, and methods of resistance. In the same vein, on November 15 and 16 the “Meeting of Our Voices of Struggle and Resistance” took place in Juchitán, Oaxaca. The final declaration stated: “We give a clear NO to the transnational projects of super-highways, dams, mines, and wind energy because they are not developing our communities, instead they are displacing us and stealing our land”.(28)

The reality is that mining is not an isolated issue. It is in effect part of a much larger phenomenon of development projects being driven by international corporations and the Mexican government. These types of projects have a very profound impact on the rural campesino population, in the sense that they do not take into account the needs and desires of the people. In the end they provoke the loss of traditional forms of subsistence and subsequent migration as well as directly contribute to the loss of indigenous cultures and lifestyles. Ultimately, the processes of resistance to these various infrastructure projects, be it highways, dams, or mines, are not separate struggles but are slowly becoming unified within Mexico to create a greater resistance to a greater issue.

… … …

- SIPAZ, “Chiapas en Datos: Recursos Naturales”. (Return…)

- Mexico, Secretaría de Economía, Direción General de Minas, Expedición de Títulos de Concesión Minera. (Return…)

- Radius Gold Inc., Exploration Projects in Southern Mexico. (Return…)

- North American Free Trade Agreement: came into effect on January 1, 1994. It basically eliminates all tariffs, quotas, and trade barriers between the United States, Mexico and Canada. (Return…)

- Adriana Estrada, Fundar: Centro de Análisis e Investigación, Impactos de la inversión minera canadiense en Mexico: Una primera aproximación. D.F., Mexico. Sept. 2001. (Return…)

- Ejido: a form of communal land in Mexico that was established by the Mexican Constitution of 1917. (Return…)

- Mexico, Secretaría de Economía, Legislación Minera. (Return…)

- Estrada, Impactos de la inversion minera canadiense en Mexico. (Return…)

- Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, “The Ten Year Track Record of the North American Free Trade Agreement”, Washington DC, 2004. (Return…)

- Direción General de Minas, Expedición de Titulos. (Return…)

- Blackfire Exploration Ltd., Projects- The Payback Barite Mine, http://www.blackfireexploration.com/default.asp?id=1. (Return…)

- Linear Gold Corp, Properties. (Return…)

- Direción General de Minas, Expedición de Titulos. (Return…)

- Gustavo Castro, Otros Mundos A.C. Chiapas, SIPAZ Interview on Nov. 20, 2008. (Return…)

- No Dirty Gold Campaign, Earthworks, Dirty Gold’s Impacts. (Return…)

- Ricardo Carrere, World Rainforest Movement, Mining: Social and Environmental Impacts, March 2004. (Return…)

- No Dirty Gold Campaign, Dirty Gold’s Impacts. (Return…)

- Ibid. (Return…)

- Elio Enríquez, “La barita, otro tesoro que no ha dejado beneficios para pobladores de Chiapas”, La Jornada, May 5, 2008. (Return…)

- Gustavo Castro, Nov. 20, 2008. (Return…)

- PROCEDE: The Ejidal Rights and Urban Lands Certification Program is a government program initiated after the reform of Article 27 of the constitution which attempts to convert communal land into private property which can then be bought and sold. (Return…)

- International Labor Organization, Convention 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, June 17, 1989. (Return…)

- NO A LA MINA, “En Guatemala 64 comunidades rechazaron la actividad minera en una consulta comunitaria”, Feb. 19, 2007. (Return…)

- Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Minería (REMA). (Return…)

- El Justo Reclamo Blog, “¡FIN A LA CRIMINALIZACIÓN DE LA PROTESTA POPULAR!”, Chiapas, Mexico. Nov. 20, 2008. (Return…)

- FNLS Blog, “ACCIÓN URGENTE: MILITARES ALLANAN VIVIENDAS DE YOLANDA CASTRO Y JAIME GONZÁLEZ DE FNLS EN CHIAPAS”, Nov. 13, 2008. (Return…)

- El Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Montaña Tlachinollan, “El Caso de Carrizalillo”. (Return…)

- SIPAZ Blog, Oaxaca: Realizan el Encuentro de Nuestras Voces de Lucha y Resistencia, Nov. 20, 2008. (Return…)