2008

02/01/2009

ANALYSIS: Mexico – Of the influenza and other problems

31/08/2009On February 10, Mexico was evaluated by the United Nations (UN) through a mechanism started in 2006: the Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Every four years, all the member States must undergo an “interactive dialogue” through which their compliance with international human rights agreements is evaluated.

On this occasion, Mexico listened to the commentaries and criticisms of a group of three countries and the member States of the UPR. Previously 3 reports had been brought before the Human Rights Council: one from the Mexican government; another from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), and the last one was drawn up from reports written by organizations of the civil society, in which the OHCHR also contributed. A hundred Mexican non-governmental organizations and 7 internationals denounced that “Mexico has not complied with its international commitments” and that torture, forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, violations of freedom of expression, and impunity still continue. The report included 60 cases of criminalization of social protest in 17 Mexican states, including Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca.

On this occasion, Mexico listened to the commentaries and criticisms of a group of three countries and the member States of the UPR. Previously 3 reports had been brought before the Human Rights Council: one from the Mexican government; another from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), and the last one was drawn up from reports written by organizations of the civil society, in which the OHCHR also contributed. A hundred Mexican non-governmental organizations and 7 internationals denounced that “Mexico has not complied with its international commitments” and that torture, forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, violations of freedom of expression, and impunity still continue. The report included 60 cases of criminalization of social protest in 17 Mexican states, including Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca.

In the final report, the UPR gave Mexico 91 recommendations, of which Mexico accepted 83 and left 8 pending. The accepted recommendations dealt with harmonization of the Mexican laws so that they comply with Mexico’s international commitments in human rights. The 8 un-accepted pending recommendations, according to the government, require “a more detailed internal analysis”; they deal with many of the criticisms presented by organizations of the civil society in its report. For example, the impunity and the institutions that should fight it (especially on issues of gender, indigenous peoples, minors, and journalists), as well as themes like military tribunals or courts, the legal concept of arraigo (pre-charge detention), and the definition of “organized crime.”

The judicial reform: a “cultural change” in favor of legality?

Many of the recommendations of the UPR focused on the Mexican justice system. For a long time now, the Mexican civil society has been demanding real reform in the area of criminal justice. The judicial reform, which was finally approved by the Senate of the Federation on March 6, 2008, attempts to integrate two contradictory tendencies: on one hand, it supports advances in human rights with the introduction of oral trials and a change in accusatory process (presumption of innocence); on the other hand, it supports the implementation of punitive measures designed to respond to fears for public security.

In the face of the insecurity that is being generated by organized crime and drug-trafficking, the Calderón administration has put the emphasis on ‘law and order‘, relegating issues like respect for human rights or the problems of impunity to the second tier, both of which are important issues in the fight against organized crime.

In the initial proposal of the reform, the most striking points of contention were: the introduction of house searches without a judicial order, the expansion of the legal concept of arraigo (pre-charge detention), the regime of exception for those accused of being involved in “organized crime”, and the existence of un-pardonable crimes (in which one cannot be released from prison). In as much, Mexican human rights organizations like the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (IACHR) and various Special Rappateurs from the UN, before the reform was passed, expressed their concerns “about the aspects of the reform which could threaten the situation of human rights.”

The judicial reform was finally approved by the Legislative Powers. However the searches without judicial orders were eliminated. The result was considered to be a “cultural change” in favor of legality by the Mexican government. Nevertheless, some called it a “Frankenstein reform”, because of its attempt to improve some parts of the justice system, but at the same time introduce repressive measures (such as the case of arraigo (pre-charge detention) and the problematic definition of “organized crime“). Others like Senator Rosario Ibarra (president of the Eureka Committee, which has worked for decades on the issue of forced disappearances), referred to the reform as a “Gestapo law.”

Two parallel justice systems and the growing risks of criminalization of social protest

The recommendations suggested by the UPR centered for the most part on the new rules that accompany the legal concept of arraigo and organized crime. The most frequent criticism involves the fact that the reform has established a two-track justice system: one track for normal crimes and the other for organized crime. The reform will be in place within a period of 8 years – the time period in which all the states must implement it. There exist serious doubts about the assumption of innocence in cases linked to “organized crime.” From a human rights perspective, it is precisely in cases of the most serious crimes in which a careful respect for personal rights is necessary in order to guarantee a fair trial.

One of the biggest obstacles for the judicial system is the definition of “organized crime” and the criteria which determine whether or not to use the laws for organized crime. In Article 16, it is defined, “organized crime is understood as an organization, of three or more persons, which conspires to commit crimes in a repeated or continuous manner, as defined by the specific law.” Many organizations and social movements fear that this article could be used against social struggles, especially because the legislation does not specify which crimes qualify as organized crime. The creation of this “regime of exception” violates the most basic principles of equality before the law, and in addition it opens the door for arbitrary rulings on the part of the State, which could be used to repress opposition movements. According to the Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, “to leave such a lax definition in the Constitution, one which does not specify which specific crimes are considered organized crime, could have very serious consequences, especially because it could be very easy to change the secondary laws and establish new crimes which should not fall within the context of national security.”

Human rights centers in Guerrero have denounced that “the loss of individual and social guarantees within the context of the war on drugs is a new threat for human rights defenders and social activists, in addition it has put the justice system and the mechanisms of protection of human rights at serious risk”. They argue that the State has “begun to criminalize human rights defenders through loss of legitimacy, the discrediting, the persecution of those who work for human rights, the fabrication of crimes, and the lack of recognition of the abuses that human rights defenders suffer.”Just in the last few months, legal action against social leaders has increased at an alarming rate all over the country. This includes a number of serious cases, before the enactment of the law, -in Oaxaca and Atenco, for example- where members of social movements were formally accused of kidnapping, blocking highways, and sedition.

Arraigo and the risks of torture

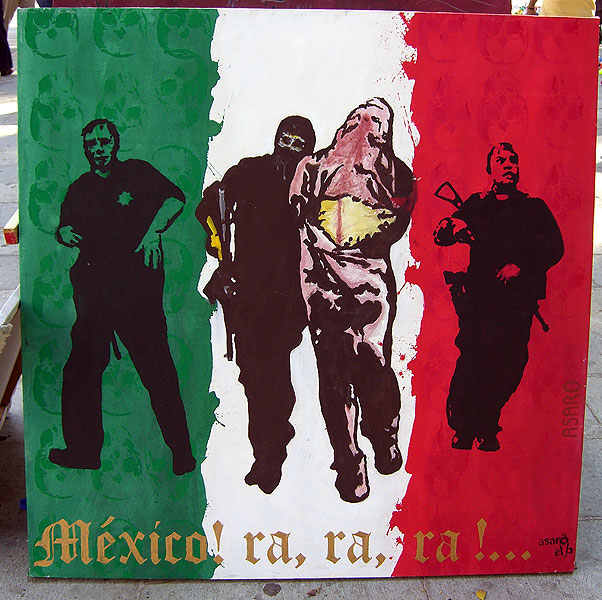

© SIPAZ

Another major fear that human rights defenders have expressed, within the context of the judicial reform and the “criminalization of social protest”, deals with arraigo, a legal concept, which appears in the federal law and is intended to be used in the fight against organized crime.

Arraigo is a special measure which exists in many penal codes in Latin America. It is described as a democratic instrument which can be used during a special criminal investigation, especially in cases where there is a risk that the person being investigated could escape. The process consists of a judicial order for “arraigo domiciliar” (a type of pre-charge house arrest) while the investigation is completed. The person must remain under constant vigilance without the possibility of leaving while the investigation is being finished. Before the reform, the maximum amount of time for arraigo was 40 days, however with the reform it has been extended to 80 days (in other countries pre- charge detention has a maximum of 2 to 7 days).

© SIPAZ

In Mexico, arraigo has a special feature: Generally they do not use house arrest but instead “arraigo houses” are used. These are administered by the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic (PGR). These locations could be public buildings like hotels, or clandestine buildings. Although legally the person who is detained under arraigo is in the hands of the judge, the person remains physically in the “care” of the Public Prosecutor (Ministerio Publico). Obviously this gives the majority of the power over the suspect to the Public Prosecutor and judicial police.

The most worrisome part of the issue of arraigo is that instead of using it as a tool to continue the investigation, it has been used to put pressure on the person being investigated and to force them to make a confession. Many of the cases of arraigo which have been denounced by human rights centers are related to “arraigo houses” where torture has been used, and there are major concerns that it could be used more frequently against protesters and social movements.

The most worrisome part of the issue of arraigo is that instead of using it as a tool to continue the investigation, it has been used to put pressure on the person being investigated and to force them to make a confession. Many of the cases of arraigo which have been denounced by human rights centers are related to “arraigo houses” where torture has been used, and there are major concerns that it could be used more frequently against protesters and social movements.

Military courts: the major concern of the judicial reform

The military court system, with its complete absence of civilian control, was another focal point of the recommendations of the UPR. It is also worth remembering that it has been the object of constant criticism and recommendations on the part of human rights organizations.

Throughout 2008, various human rights organizations stated the necessity that the military justice system be exclusively limited in its jurisdiction to crimes committed within the military structure without “extending itself to investigations and prosecutions of human right violations.” Last year, the Human Rights Center Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez (Centro ProDH) recorded 120 cases of abuse committed by members of the Mexican Armed Forces, including illegal searches, physical attacks, torture, and arbitrary detention. They pointed to Guerrero as the state most affected in this sense. NGOs have affirmed an urgent need to establish civilian control over the military, and they are awaiting the decision of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN), which will discuss the question of military jurisdiction in cases involving civilians who have been victims of human rights violations. Luis Arriaga, the director of Centro ProDH, stated that the use of military justice in these cases “perpetuates impunity and undermines civilian control, which in any democracy should have control over the military institutions”.

What is next?

Differing from the issues with the content of the reform, another major challenge is its actual implementation. In its 2008 report, Human Rights Watch pointed out the “double face” of the Mexican State, which has signed numerous international agreements dealing with the defense and promotion of human rights and maintains a high profile on the international level in the area; nevertheless, these same agreements seem to become dead letters the moment they are applied in the country. Although one would like to look at the judicial reform as an advance, or as stated at the beginning “a cultural change”, it still remains to be seen what will actually change.

One final concern involves the capacity of social movements and civil organizations to act as a counterweight to the State’s repressive tendencies. Or if organized crime, and the thousands of deaths it brings every year, will be an excuse for the State, with the approval of an international community concerned with security issues, to legalize repressive penalties which violate human rights.