ANALYSIS: Mexico – Of the influenza and other problems

31/08/20092009

04/01/2010In July, the Human Rights Commission of the Federal District (CDHDF) questioned the fact that Mexico, which is number 13 on the global economic scale, occupies number 108 on the Global Peace Index, ranking below even African nations like Rwanda and the Congo. This index measures perceptions of violence in 144 nations. Taking into account the fact that peace is not only the absence of direct violence (war) but also the lack of cultural and structural violence, the index also includes factors like education, material well being, and the defense and promotion of human rights.

As part of the Second National Meeting of Human Rights Defenders, which took place in Mexico City (August 2009), various traits relating to the situation of human rights were noted. Among them:

- “There is a double discourse by the State. On the international level there is a façade indicating a concern with human rights, while on the internal level not only is there a lack of commitment to defend and support human rights, but there exists a barrier to these rights, and a lack of implementation of international human rights standards.”

- “The militarization in our country, with the pretext of the fight against organized crime, has been aggravated by the trials held in military tribunals of members of the military who are presumed to be human rights violators. This has generated a situation of defenselessness for the victims.”

- “Deficiencies in the implementation and administration of justice, which have led to impunity.”

- “The criminalization of human rights defenders, through the use of penal codes to impose sanctions on defenders, systematic aggression by the police against protesters, harassment, and hostility.”

- “Direct aggressions against the lives and safety of family members of political prisoners, prisoners of conscience, and human rights defenders, as well as arbitrary detention, illegal detention, torture, forced disappearance, and killing. The aggressions are especially grave in indigenous communities.”

- “Campaigns aiming to discredit human rights defenders, social activists, and their work.”

In the case of Chiapas, in addition to seeing these same tendencies, in the last few months there has been a serious deterioration in the situation of human rights in the State.

Impunity

In October, the Observatory of Social Conflict of Serapaz (Services and Consulting for Peace) revealed that between January and August of this year, 24% of the social mobilizations in the nation gathered with the objective of ending impunity.

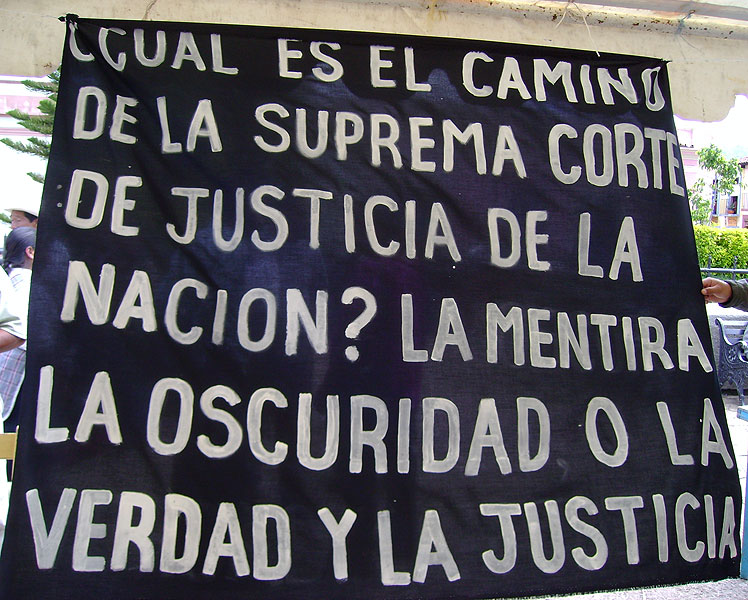

In Chiapas, the most widely know case –as well as the most paradigmatic- dealt with the fact that between August and November, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) freed 35 indigenous men who had been sentenced for the killing of 45 indigenous people in the community of Acteal, municipality of Chenalhó (Highlands) in 1997. Twenty-two prisoners in the same case will undergo a re-trial for these crimes.

The SCJN came to this conclusion by arguing that the sentences were based on proof obtained in an illegal manner and in false testimonies by the Attorney General’s Office (PGR). They emphasized that the rights of these prisoners to due process and an adequate defense had not been respected and because of this their decision represented a major blow to impunity and strengthened the rule of law.

On the other hand, the Civil Organization Las Abejas (of which the victims of Acteal were a part) denounced this decision: “The little justice that had been achieved in the case of Acteal, the SCJN has converted to impunity in just a few days.” The Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (CDHFBC), responsible for the defense of Las Abejas, stated: “Instead of working towards true justice and strengthening the ‘rule of law’, they opted to free paramilitaries, who were clearly identified as the material authors by survivors and direct witnesses to this crime against humanity.”

It is important to remember that the SCJN did not determine that those freed were innocent. Because of this, many have denounced the gap between a sound judicial response and the demand for justice in the case. They have also questioned the resolution for not taking into account the context in which the massacre of Acteal occurred and the war which continues in Chiapas.

Backing up what human rights organizations have been denouncing for more than a decade, official United States documents, recently un-classified, were released in August by the National Security Archive, indicating the direct support that paramilitaries received from the Mexican Army as part of a counterinsurgency war carried out against Zapatista support bases during the 1990s. In addition, at the end of October, the State Attorney General’s Office stated that it had sources, which implicated various high level federal and state authorities for omission and negligence in the case of Acteal.

Another concerning effect of the SCJN decision is the impact that it has had in Channahon and other regions of Chiapas where it was seen as supporting impunity, opening up the possibility of the revival of paramilitary actions. Demonstrating some political realism, the Chiapas government has sought to prevent the return of those freed to Channahon in order to avoid confrontation. It has offered them land, housing, and work. Las Abejas denounced the limited nature of these measures of contention. Since August, they have also denounced that the state government has sought to divide them, as well as link them to armed groups.

Human Rights Defenders and Criminalization of Protest

In presenting its Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in Mexico in the middle of October, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) in Mexico questioned the Mexican authorities for lacking a political structure, which reduces and eliminates risks for human rights activists. It stated that of the 128 accusations of aggression against human rights defenders in the last three years, 98.5% remain un-resolved. The UNHCHR noted an increasing ‘stigmatization‘ of defenders, especially by authorities, as they are being identified as “defenders of criminals, or they say that they are trying to de-stabilize the country; they make money off the cases and they exaggerate the problems.”

In the case of Chiapas, a growing criminalization of social protest has been observed, in many cases carried out by the state government. This criminalization has affected independent organizations, human rights defenders, and the local Catholic Church, and it is very similar to the repression, which occurred in the state in the ’90s.

On September 18, the Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (CDHFBC) denounced an armed attack by the Organization for the Defense of Indigenous and Campesino Rights (OPDDIC) against one of its members, in the Ejido Jotolá, in the municipality of Chilón. This latest aggression, putting one of its member’s personal security in direct danger, has occurred in a context of vigilance, aggression, and discrediting by diverse actors and the media. Two months after the events, the accused attackers were detained and then released, according to the population of Jotolá, threatening revenge.

On November 19, the National Front in the Struggle for Socialism (FNLS), another particularly targeted group, published a press release titled “Criminalization and persecution by the state government of Chiapas against a social movement” in which it describes numerous hostilities, which have been carried out against them.

Just days before, the newspaper La Jornada published parts of a report titled, “The current situation in the municipality of Venustiano Carranza” written by the State Attorney General’s Office (PGJE). It attempts to document the existence of a “subversive network,” which would be planning destabilizing actions for 2010, and whose leader would be the Catholic parish priest of Venustiano Carranza, Jesús Landín. This report appears to “justify” the hostilities denounced by the CDHFBC, the diocese, and other social actors, as well as the police and military operations in and around Venustiano Carranza.

The FNLS rejected outright the accusations in the report and denounced the “strategy of counterinsurgency” directed “fundamentally at organized spaces and actors which have stayed independent of the government and of political parties and which above all have denounced the injustice and systematic violations of human rights which have been committed in Chiapas under the government of Juan Sabines Guerrero.”

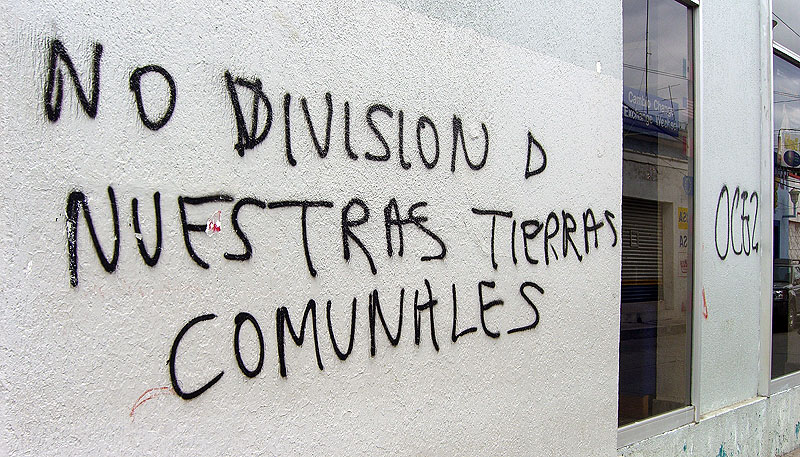

Another organization mentioned in the document and subject to repression in the past months is the OCEZ-RC (Campesino Organization of Emiliano Zapata – Carranza Region). Interestingly the recent repression occurred even though this organization, whose demands are agrarian in nature, had signed a “pact of governability” with the State government, a pact that included the economic resources and a compromise to not protest or take up agrarian issues.

Beginning on October 26, around 150 members of the OCEZ began a sit-in strike in the center of San Cristóbal de las Casas in order to denounce the police/military intimidation in their region and to demand the freedom of members detained during September and October. Amnesty International asked the Mexican government to investigate the accusations against police officers of Chiapas for the torture of leaders of the OCEZ and to guarantee a fair trial for José Manuel Hernández Martínez, who was being held in solitary confinement in a high security prison far away from Chiapas. On October 30, members of the sit-in occupied the offices of the Organization of the United Nations (ONU) in San Cristóbal.

On November 23 the three members of the OCEZ were freed on bail paid for by the State government, which sought to re-open negotiations by suspending the remaining arrest warrants. The OCEZ condemned the repression, maintained its demand for land and indemnifications for the family members of two people killed during the apprehension, but it accepted nonetheless.

As for the diocese, at the end of November, in a public declaration from the priests and nuns of the Southern zone declared: “Instead of slander, hostility, and persecution we hope that the Governor will join together with the people in order to defend the sacred Chiapas land, lungs of the nation, and give an example of respect for rights which follow the Constitution and which defend the international commitments made by Mexico.”

Disputed Territories

The 2009 Report of Amnesty International mentions the case of Mexico: “Various projects of inversion and economic development provoked protests in some local communities because of the lack of adequate consultation and for the possible negative effects of these projects on the social and environmental rights of the communities. The indigenous communities were the victims of an especially high number of reprisals.”

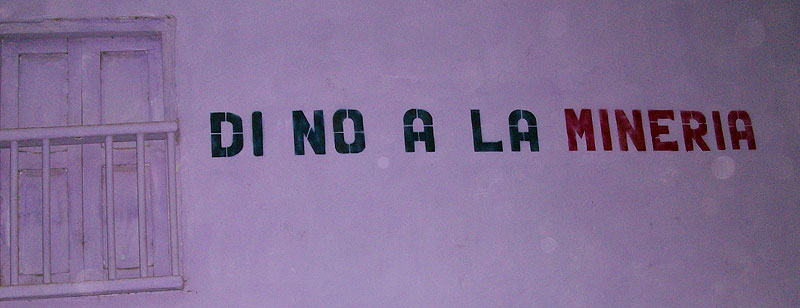

In the case of Chiapas, the majority of recent social conflicts –although they might appear isolated- are the result of territorial issues: the resistance to mining exploitation in eight counties or the construction of the highway between San Cristóbal and Palenque (Mitzitón for example), the fight for local control over the waterfalls of Agua Azul (the case of Bachajón), against the high electricity prices (see the focus article), among others.

The case of Marinao Abarca exemplifies the use of criminalization of social protest. In August, Abarca, an opponent to the mining exploitation in Chicomuselo (mountains of Chiapas) was arrested at the roadblock, which he had maintained since June in order to halt the activities of Blackfire (a transnational Canadian corporation). He was freed a week later, although the harassment against the anti-mining movement was maintained, as was seen at the Meeting of the Mexican Network of those Affected by Mining (REMA) at the end of August in Chicomuselo where police infiltrated disguised as journalists.

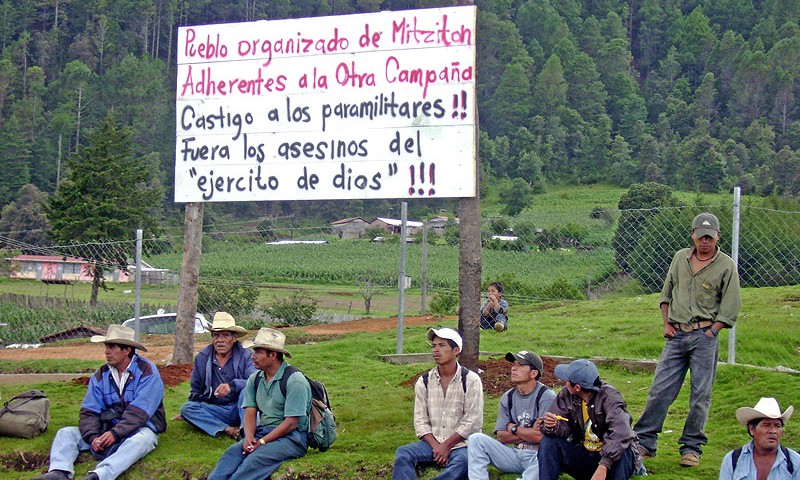

At the end of July, members of the Other Campaign in the ejido of Mitzitón established a roadblock of the highway in order to make various demands: the cancellation of the highway from San Cristóbal to Palenque (which supposedly will cross through the ejido of Mitzitón), the self determination of communities, and justice for Aurelio Díaz Hernández who was ran over on July 21.

In the case of Bachajón, eight members of the ejido have been held in jail since April. The population of Bachajón continues seeking their liberation and has denounced that “state and federal police continue illegally occupying” their territory.

Conflicts regarding recuperated land continue to exist. In August, more than 15 people were wounded during a confrontation between Zapatista support bases and militants of the Organization of Regional Coffee-growers of Ocosingo (Orcao) over the land of Bosque Bonito and part of El Prado, in the zone of Cuxuljá, municipality of Ocosingo. In September, indigenous persons of the Rural Association of Collective Interests-Union of Unions (ARIC-UU) and support bases were involved in a confrontation over 200 hectares of disputed land in Santo Tomas, in the municipality of Ocosingo. It resulted in one death, and at least 15 injured and 4 detained.

The State Government: Contradictory Responses

The State Government has come together with and signed various agreements with international organizations. At the end of July, Chiapas became the first state in the world to include in its Constitution the obligation to comply with the Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations (UN). In September, the International Labor Organization (ILO) and governor Juan Sabines expressed the possibility of beginning a work agenda to strengthen and refocus attention on indigenous communities in the state.

At the internal level, on the other hand, the government of Chiapas seems to “deny or minimize existing conflicts” (Hermann Bellinghausen, La Jornada). In the face of denunciation of mining projects, it stated that there are no such projects, and in any case such projects would actually benefit the people. It has denied that the highway from San Cristóbal to Palenque would pass through locations that are opposed to it. In the case of the Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, it condemned the aggressions against it. According to a report issued by the state government after a meeting with Bishop Felipe Arzimendi, “we discussed, among other things, the issue of mining in Chiapas and the need for an in-depth analysis which benefits people in the locations where the mining takes place. (…) Juan Sabines offered to Bishop Arizmendi his willingness to meet the parish priest of Carranza and to clear up any misunderstanding that might exist.”

The state government seems to have a solution to all the conflicts although it refuses to recognize the role it has had in generating them, and it has not dealt with the root causes of the conflict. On the other hand, some ambiguous statements have not helped to build space for the defense and promotion of human rights when in November, for example, the Government Secretary Noé Castañon asked the population to “not be deceived by those snakes with lambskin who on one hand ask for peace but secretly promote violence. (…) No one should fall for those who wish to use the people as cannon fodder in order to begin bloodshed in 2010, or before, because of personal interests.”

Militarization and Human Rights

In the case of Chiapas, we must discuss re-militarization more than militarization. Since the armed uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), Chiapas has been the most militarized state (in terms of number of bases) in the nation. Certainly, in the last few weeks, there have been many denunciations of searches and military incursions in the Central zone (around Venustiano Carranza), in the Jungle Border region, as well as in the Highland zone on the anniversary of the founding of the EZLN.

Returning to the national context, the complaints of violations of human rights have multiplied due to the participation of the Army in the fight against drug traffickers, which has deployed 45 thousand members without managing to reduce the level of violence attributed to these illegal networks.

Nevertheless, the director of human rights of the Sedena, General López Portillo as well as Felipe Calderón have a tendency to minimize and discredit these criticisms. In July, López Portillo stated that “the majority of crimes which are committed are the result of negligence, collateral to their operations, and because of a lack of knowledge of the consequences of a human rights violation.” In August, during the Closing Summit Mexico-USA-Canada, Felipe Calderón stated that his government has complied “scrupulously” with its commitments to human rights and that “those who say otherwise, should prove one case, just one case.” In response, 5 civil human rights organizations sent a letter in which they described 7 cases of violations of human rights by members of the military against civilians, all of which occurred during this term.

In August, the Secretary of National Defense announced that the United Nations (UN) would measure their success in terms of human rights. The national ombudsman José Luis Soberanes, stated that this announcement was really only a “a nice show.” The federal government’s intentions seem to have been more important than the results, because in August the United States decided to give 214 million dollars to Mexico as part of the Merida Initiative1 which seeks to help Mexico in its fight against organized crime.

… … …

- The Merida Initiative plans to give 1.4 billion dollars to Mexico over a three-year period for anti-drug cooperation. 15% of the funds are conditioned on a US State Department report on the human rights conditions. (Return…)