2009

29/01/2010

ANALYSIS: Serious challenges to Mexico regarding human rights

31/03/2010For the first time in 16 years, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) did not celebrate the anniversary of the armed uprising that took place on January 1, 1994—at least not publicly. However, the “Caracoles” (Good Government Council Seats) did close on the anniversary, generating certain speculation and fomenting rumors around the Zapatistas’ plans for 2010, a symbolic year as it is the bicentennial of Mexican Independence (1810) and the centennial of the Mexican Revolution (1910). Within this framework the legislative members of the House of Deputies’ Commission on Indigenous Affairs claimed that a new indigenous rebellion is latent, and not only in Chiapas. The Commission argued that the absolute poverty rate has increased, reforms regarding indigenous autonomy have stagnated, and policies regarding this sector of society have been abandoned.

Over the last few months many voices, both at the local and national levels, have expressed concern over what they see as perhaps happening this year. Politicians, corporate and social organization leaders have warned that there is a possibility of social upheaval. Such a situation could allow some to negotiate funding, social programs or different types of concessions while others may use it as a pretext to confront, repress, or fragment the opposition.

This scenario, certainly tied to a collective imagination shared by a large portion of the population, marks a change within the unresolved armed conflict in Chiapas. The theme, which had been sidelined by the media and the national political agenda, has been revived and has become the object of initiatives put forth by various political actors. Some seem to attempt addressing unresolved points within the negotiation process that was once held between the EZLN and the federal government (suspended since 1996); others seem to think it is a continuation of the counterinsurgency logic.

The Good News…

In a seeming attempt to prevent the emergence of a new rebellion in Chiapas, both the state and federal governments presented initiatives between the months of November and January. On November 24, the local Congress announced that the Zapatista Good Government Councils (JBG, Juntas de Buen Gobierno) had asked for legal recognition. The JBGs from the five Caracoles later refuted that statement, claiming that “We the Zapatistas do not need to be recognized by the bad government that is not of the people because we are already recognized by our people who have elected us, in addition to having been recognized by many peoples, both nationally and internationally. (…) All of these lies from the bad government, from its deputies and accomplices, are part of a counterinsurgent strategy intended to confuse public opinion and undermine our peoples’ resistance in the struggle to build our Autonomy.”

On December 29, the local Congress approved the “Chiapas State Law on Indigenous Rights,” an initiative that was proposed by the state governor with the objective of “recognizing the San Andrés Accords”. It is said to have been designed to allow indigenous peoples and communities the same opportunities for development based on respect for their customs. Analysts and organizations have expressed concern regarding the propagandistic character of the initiative: on the one hand they have stated that the framework of recognition for indigenous rights remains limited “whenever they do not violate the state and federal constitutional precepts or the rights of third parties”; and on the other hand, they called into question the lack of consultation with the groups that would be affected by this law.

In January, the federal Congress relaunched the Concordance and Pacification Commission (COCOPA, Comisión de Concordancia y Pacificación), a legislative body created in 1995 to further negotiations between the federal government and the EZLN. It had been inactive for several years. Senator Carlos Navarrete of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD, Partido Revolucionario Democratico) stated that the COCOPA will look to avoid future armed uprisings and added that it won’t await the emergence of further complications before acting. Navarette claimed to find it important that the situation in Chiapas be attended to, that the government be informed about it, and that existing issues be resolved. In early January COCOPA members traveled through Chiapas allegedly to locate all of the actors that are linked either directly or indirectly to the EZLN and to present them with an invitation to recommence negotiations.

All of these initiatives bring to mind previous stages of the conflict in which the State appeared to want to address the structural causes behind the 1994 uprising, though without the participation of the Zapatistas. In any case, these moves are nonetheless to be seen as actions “for the better.” Parallel to this, unfortunately, elements that appear to respond to a strategy “for the worse” have been continuously denounced.

The Bad News…

Since early November, both roadblocks and police/military raids have been denounced in communities throughout the state. The actions were putatively taken in order to promote disarmament. On December 30, 36 artillery vehicles from the National Defense Ministry (Sedena, Secretaría de Defensa Nacional) were deployed in Chiapas. According to state sources, “this operation of deterrence [has been put into effect] to respond to any contingency or disturbance that may occur in any of the 118 municipalities; it includes patrols and flyovers in zones that are considered to be red alert spots.” The Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center (CDHFBC, Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de las Casas) delved more deeply into the issue stating that “in late 2009 the government implemented operational measures to monitor movements in rural areas, survey all modes of communication, carry out disarmament campaigns in indigenous communities, install police roadblocks in various locations throughout the state of Chiapas, and take advantage of the discourse of the current fight against organized crime by repositioning army units in communities with a history of civil resistance.”

However, it is important to point out that tensions have subsided in the municipality of Venustiano Carranza, one of the major hot spots during 2009. On December 23, after coming to an agreement with the state government on political, economic and social issues, the Emiliano Zapata Campesino Organization – Carranza Region (OCEZ-RC, Organización Campesina Emiliano Zapata – Región Carranza) ended the sit-in it had held for close to two months in San Cristóbal de las Casas. During negotiations, the state government reiterated that it has no power to impede the militarization of indigenous communities, given that this is a federal matter.

Another issue that has been reiterated throughout 2009, both in Chiapas as well as at a national level, has been the growing criminalization of human rights defenders as demonstrated by ongoing surveillance, harassment, threats and raids, among other crimes. In December, during the celebrations of International Human Rights Day, the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center published a special bulletin that contained the following denunciation: “This year work in defense of human rights has been criminalized to the point that human rights defenders have been equated with organized crime and subversive networks supposedly intent on destabilizing the State in 2010.” One of the most recent examples of this tendency was the number of denunciations made since last November of several acts of harassment (including death threats) directed at Adolfo Guzmán Ordaz, a member of Enlace Comunicación y Capacitación in Comitán.

This form of criminalization is even more evident in cases where the individuals organized in defense of human rights are not members of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) but instead are members of social or indigenous organizations. An extreme example of this occurred at the end of November with the murder of Mariano Abarca Roblero, a member of the Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining (REMA, Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Minería) and the Civic Front of Chicomuselo , which oppose investment plans made by the Canadian mining company Blackfire. Abarca had denounced both death threats against his person as well as pressure he was receiving from the municipal president of Chicomuselo who was, according to representatives from Blackfire, receiving large profits and kickbacks from the company.

One key element in the tendency toward criminalization has been the role of the media, an aspect clearly illustrated in the following two cases.

Bolón Ajaw: Contradictory Versions

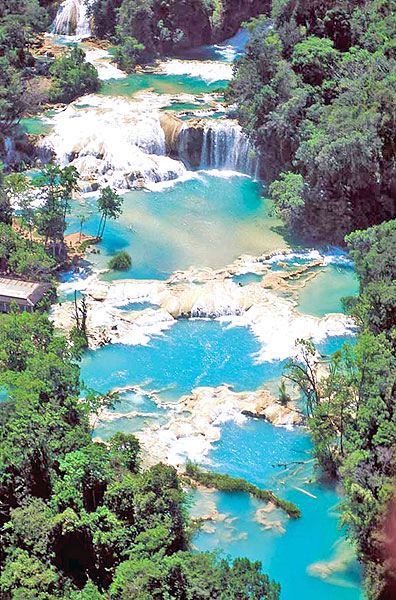

On February 6, a new conflict presented itself within the territory of Bolón Ajaw in the municipality of Tumbalá (northern Chiapas). The area has been occupied by Zapatistas since 1994 and falls under the jurisdiction of the autonomous municipality of Comandante Ramona. It lies some four kilometers from Agua Azul and contains waterfalls that have yet to be exploited for touristic purposes.

The Miguel Agustin Pro Juarez Human Rights Center entitled one of the entries in its media synthesis “Confrontation in Chiapas spurs media campaign against indigenous communities–the Mexico City media emphasizes ‘executions’ and ‘disappearances’ on the part of the Zapatistas on front pages.” The Chiapas Attorney General’s Office (PGJE, Procuraduría General de Justicia del Estado) claimed that the conflict had left one dead, five detained and 28 injured, 13 of whom were hospitalized with bullet wounds as well as injuries sustained from melee weapons and beatings. According to the PGJE, the conflict erupted in January when the Zapatistas from Bolón Ajaw requested support from sympathetic communities in Oxchuc, Alan Sacjun, Salto del Tigre and Bachajón in preventing members from the Organization in Defense of Indigenous and Campesino Rights (OPDDIC, Organización para la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas y Campesinos) from clearing the path that connects the Agua Azul waterfalls to those of Bolón Ajaw (a course of action said to be undertaken in order to bring in tourism revenues).

Other media outlets reminded the public of prior criminal charges against OPDDIC that have been pending since February 2008; such media coverage included denunciations of attacks, injuries, threats and murder attempts against NGOs and EZLN support bases that took place in Bolón Ajaw. Still others alluded to the denunciation made by the Morelia JBG on January 23, 2010 which referred to attacks made by OPDDIC in the same area. Adherents to the Sixth Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle, grouped under the Otra Jovel, denounced the events that took place in Bolón Ajaw, stating that “the residents were attacked several years ago by other indigenous people who had been organized and armed like paramilitaries by the government.”

In a communiqué from February 11, the Morelia JBG clarified the recent events in Bolón Ajaw and found that “the employment of traps such as those used by previous governments includes the fabrication of crimes in order to justify repression.”

© Red MyC zapatista

In regard to the conflict of February 6, the JBG stated: “[According] to the OPDDIC’s lies, we surprised [them] in the early morning, scaring the residents, when we were the ones who were thus surprised. (…) Due to their indiscriminate shooting in Bolón Ajaw, they ended up killing their own compañeros.”

On the subject of those detained, they explained, “The seven individuals said to have been kidnapped have already been returned alive and as healthy as they were when they arrived. They signed a document upon their release recognizing that they had been respected. (…) We proposed that they be released upon the condition that they promise not to return to the area and that tranquility be reestablished. This was our word, and we complied with honor and truth.”

The communiqué also mentioned “the message from Juan Sabines Guerrero is to create a dialogue in regards to the problem when in fact he contrarily insinuated that the army will be deployed, thus destroying the dialogue between the EZLN and the federal government and bringing about more hostility.”

On February 12, the CDHFBC published a statement in which it claimed that “the Chiapas government is attempting to avoid its responsibility in the denounced conflict that has continued since 2007. The government is also making an effort to blame the Zapatista Support Bases for the armed attack against the Zapatista community of Bolón Ajaw.” The statement denounced that “the federal government is pressing for a military intervention against the Zapatistas and is increasing intelligence operations carried out by joint forces.” The full report, which was published later, emphasizes that the Agua Azul-Bolón Ajaw region “has become a focal point for the implementation of tourist plans and projects, a situation that has made the region into an interest to be controlled.” It is important to point out that the surrounding area has been a hot spot since at least 2008 as in the case of members of the Other Campaign from the ejido of San Sebastián Bachajón that control the entrance to the waterfalls at Agua Azul.

Another Example: Evictions in Montes Azules

On January 22, some 120 indigenous people that have resided for the past 20 years in El Semental and Laguna San Pedro within the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve were evicted by federal police, military personnel, and officials from the Federal Attorney General for Environmental Protection (Profepa, Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente). The state government later claimed that the eviction was carried out in a non-violent fashion, and it promised that the families would be relocated. On January 26, the government stated that planned reforestation projects and the establishment of an eco-tourism center, would require the eviction of seven other residents.

A January 29 communiqué from the La Garrucha JBG contradicts this version in denouncing the violent eviction of the Laguna San Pedro community. The JBG claims that the Zapatista residents were forced to board helicopters and were transported to the city of Palenque while their homes were burned along with all of their belongings.

In regards to the eviction, the Chiapas Peace Network (Red por la Paz en Chiapas) issued a communiqué which highlighted “the stigmatizing portrayals of the evicted as well as claims that are made without previous investigation or use of non-official sources. We assert that journalism that presents only the government’s version of events jeopardizes the security of displaced families as well as that of the human rights defenders that accompany them and of the residents of communities threatened with eviction.” It further added: “As civil organizations that work in the area, we do not accept the proffered excuse of “conservation and protection of natural resources” that has been employed at several levels of government to obtain territorial as well as social, political, and economic control over one of Chiapas’ most bio-diverse regions.”

… … … … … …

IN BRIEF

Militarization and Human Rights

© SIPAZ

Both the annual Human Rights Watch report on Mexico and the Amnesty International investigation “Mexico: New Reports of Human Rights Violations by the Military” continue to stress the marked increase of abuses at the hands of the military in the last few years. Additionally, the federal government continues, generally and by various means, to justify the militarization of public security, minimizing the human rights violations committed by military personnel as well as attempting to discredit national and international organizations that have documented these types of abuses. It is estimated that the war on drugs has cost some 16,500 lives since the start of Felipe Calderón’s administration. That number exceeds the homicide rates found in cities such as Medellín and Naples during its most violent times.

The Mérida Initiative

© SIPAZ

In mid-December, despite the concern expressed by several Mexican legislators regarding the claims of rights-violations directed at the Mexican military, the United States Senate approved a USD 231.6 million support package for Mexico under the Mérida Initiative for the 2010 fiscal year. On February 1, US President Barack Obama requested that USD 310 million be allotted to the Mérida Initiative in the 2011 budget. Following the three initial years of the plan, which involved the sale of airplanes and equipment, it is to be imagined that these funds will finance a further stage in the plan and will be spent on “institutional support.” In contrast, some media sources have claimed that the US budget will put aside USD 4.6 billion to strengthen border patrol and advance the construction of the border wall. These moves have been seen as reflections of a further deterioration of extant US immigration policy.

Impunity

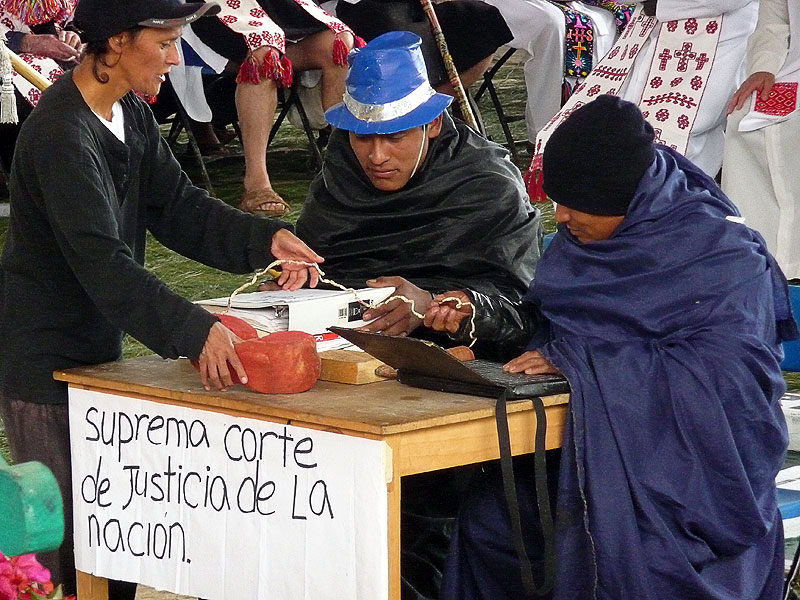

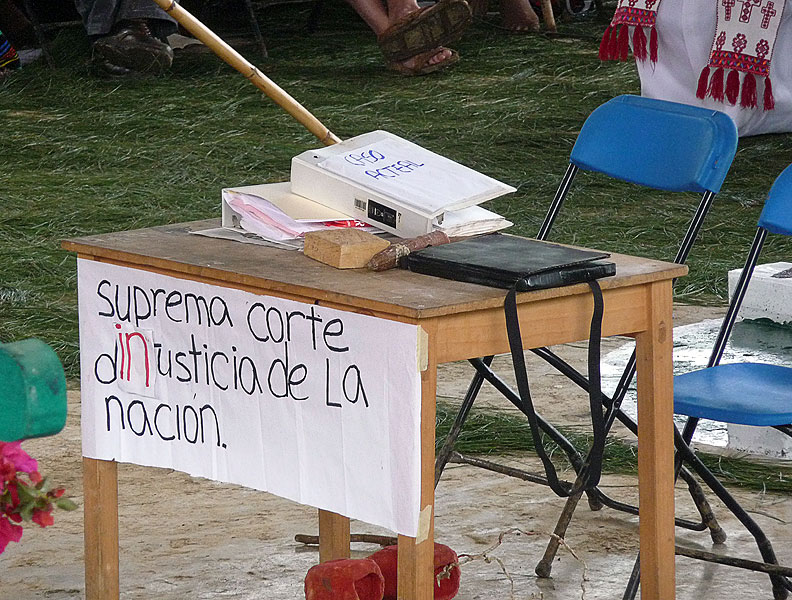

- Twelve years after the massacre at Acteal, the Abejas Civil Society (La Sociedad Civil Las Abejas) held a Forum of Conscience and Hope, Building the Other Justice on December 21. The following day, in the presence of more than 600 forum participants, Acteal was declared a “Site of Conscience.” A representative from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico was present at the event and defined the massacre at Acteal as “the [single] bloodiest event in the recent history of Mexico,” and went on to assert that “forgetfulness and impunity are not the responses expected from a democratic State that respects human rights.”

- At the national level, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights determined the Mexican Government guilty in the case of the 1974 forced disappearance of the social activist Rosendo Radilla Pacheco, a resident of the state of Guerrero. The Court also denounced the massive, systematic rights-violations that took place during the “Dirty War.” It called into question the military jurisdiction and ordered the Mexican authorities to enact reforms to guarantee that human-rights violations committed by military personnel against civilians be tried in civilian courts.