ANALYSIS: Chiapas – Carrot and Stick?

26/02/2010

ANALYSIS: Current Events – Of changes and continuities

30/07/2010On 8 March 2010, hundreds of people responded to the call made by women of Las Abejas of Acteal to march in observation of International Women’s Day. When the march arrived at the military base of Polhó, Las Abejas denounced the role of the military in Mexican society: “All Mexicans suffer abuse at your hands, in addition to illegal searches, physical aggression, torture, rape, and arbitrary arrests.” They continued by reminding the soldiers that “you also have mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters; they could also be subject to privation if you obey orders given to you by your superiors without reflecting on them.” They concluded by citing the words of the late Salvadorean bishop Oscar Romero: “No soldier has the obligation of obeying an order that contradicts God’s law. No one has to comply with an immoral charge.”

This is a call to civil disobedience—a call to disobey a law or order that one, in his or her conscience, considers it to be unjust, illegitimate, and contradictory to values basic to the democratic ideal. It is a tool of struggle that we invite you to consider.

Thinking about Civil disobedience through a Mexican example (3)

We would like to illustrate the concept of civil disobedience by means of an example from Mexico and Chiapas. Although the term has not been explicitly used to describe this struggle, it nonetheless fits the case. The example is of citizens who decided not to continue paying for electricity so as to denounce the unjust and arbitrary prices charged for such, in addition to the risk of privatization. This movement has a presence in several states of Mexico, organized by the National Network of Civil Resistance to High Electricity Prices (the National Network, from here on). In Chiapas, this struggle is led by the State Network of Civil Resistance “The Voice of Our Heart,” which has a strong presence in the Central and Highlands regions of the state, and by PUDEE (United Peoples in Defense of Electricity) in the Northern Zone. (For more information on the history of this movement, see the SIPAZ reports of November 2009 and December 2004.)

Civil disobedience is as much a tool of democracy as it is of struggle. To begin to identify the characteristics that allow for this combination, one can ask: why is such disobedience called civil?

A first response would be to highlight the struggle’s civic nature; it refers not to special interests but to the common good, so as to improve society. Those who struggle in civil resistance to high electricity prices are struggling not to receive preferential prices but rather so that the interest of the people win out over the economic interests of a few. It is also civil because it recognizes the function of the law and of the existing accords in democracy: it does not oppose the law itself in general but rather to its specific injustices. He or she who disobeys in a civil manner is not a criminal- but rather a dissident. He or she “does not remove himself or herself from the political collectivity to which he or she belongs […] but rather rejects complicity with such” (JM Muller). In a recent communiqué released by the National Network it is stated that “We don’t reject just prices; we oppose abuse.”(4)

Beyond being civic, such disobedience is civil because it respects the principle of “civility” among citizens: it is non-violent both in its means and ends. When the Movement of civil resistance to high electricity prices in Candelaria, Campeche, received the National Prize for Human Rights “Don Sergio Méndez Arceo” in March 2010, the prize committee noted that the Movement’s “just and non-violent struggle is a warning to the powerful and a call of solidarity to the citizenry.” Civil disobedience certainly violates the law considered to be unjust, and so it allows for the State to criminalize or repress such. In this sense, much determination is needed to sustain non-violent attitudes and actions.

Civil disobedience is not clandestine; rather, it is practiced publicly, and indeed seeks the greatest social diffusion possible. This is a strategic wager, as the idea is to convince the public of the righteousness of such disobedience. Beyond civil disobedience to unjust laws itself, then, the struggle implies a campaign of raising awareness, as those who are to pressure the government will not be solely those who disobey but also the public in general, if and when it is convinced of the legitimacy of such actions. Those who visit the communities of the Northern Zone of Chiapas can see the PUDEE plaque on display in many homes; it is in this sense a public affirmation of this act of civil disobedience. At the national level, this campaign utilizes several different measures: “we have carried out marches, meetings, intermittent blockades of roads, forums, encounters, closings of public buildings, distribution of flyers, informational traffic stops, journalistic murals, newspaper and round table discussions, empowering workshops for the education of community leaders, and hunger-strikes like those that were carried out by our comrades who are political prisoners.”(4)

To engage in civil disobedience is to act responsibly. To act outside of the law implies risks; the punitive sanctions that follow the breaking of the law tends to deter those who would do so. To accept confronting the institutional system of justice does not signify accepting its final judgment: if the law that one breaks is truly unjust, then punishment for disobeying it is similarly unjust. In Campeche, three individuals have been imprisoned for their active resistance, but the campaign that seeks their release has aided the campaign aimed at increasing the public’s awareness. Various victories have been secured: Besides those imprisoned having received the prize mentioned previously, Amnesty International has named them prisoners of conscience in the same month.

Moreover, civil disobedience not only opposes injustice; it also proposes action. It is civil because it constitutes a force for constructive change. It does not oppose itself to democracy but rather seeks to strengthen it by means of the exercise of citizens’ counter-power. The proposal of the National Network asserts that electricity should be considered communal property, subject to public redistribution with fair prices. The Network affirms that “we have organized around our needs, and we have all jointly gathered in assembly and determined the price that we can afford for the communal support for the maintaining of the electrical system.” As long as the public service of the Federal Commission of Electricity (CFE) is not improved, the people will organize and train themselves to repair electrical infrastructure when such is needed.

These points distinguish the difference between civil disobedience from a criminal activity, and as such they demonstrate its democratic legitimacy. Civil disobedience also finds its basis in its exceptional character; it constitutes the action of persons who see themselves as being “obligated” to break the law due to the lacking response of the authorities. It is a final means to be used after legal methods have been exhausted. For instance having question the CFE after having received abusive bills.

Combining ethical consistency with political force

Now, if the political, public, non-violent, responsible, constructive, and exceptional characteristics of civil disobedience respond to its ethical and strategic urgency, there still lack elements that would allow it genuine political efficacy. To engage in civil disobedience is to do more than express one’s conviction; to do so is to exercise the power that corresponds to the citizenry of any given society. Civil disobedience seeks results; it works to oblige the State to nullify or reform unjust laws.

Because of this, civil disobedience must be collectively organized: the more people that are mobilized, the greater will be the impact. Collective organization also helps to reduce the probability of making mistakes. The state and national organizations by means of which those who resist high electricity prices organize themselves have already been mentioned. Furthermore, given that disobedience implies having the strength to confront the risk of punishment, its collective nature helps to transcend the fear of repression and, insofar as it is possible, avoid such. This solidarity is strongly manifest in the following, one of the principles of the National Network: “if they hurt one of us, they hurt us all.”

Civil disobedience must also be enduring. Power does not capitulate when confronted by short-lived protests. The longer a given action lasts, the greater the dilemma for the State: not to act, or to repress. These are two options that do not work in favor of the government, as they both reflect a loss of its legitimacy; the other option is to pay attention to the demands made by the citizenry. If the development of a national resistance to high electricity prices is a fairly recent one (May 2009), in Chiapas it began at least in 1994 and has gained much strength in recent years. This characteristic implies preparing oneself to face repression. In this sense, those who have decided not to pay for electricity have exposed themselves to electricity-cuts and the loss of access to government social programs. They have denounced both measures as illegitimate, together with the prices they face.

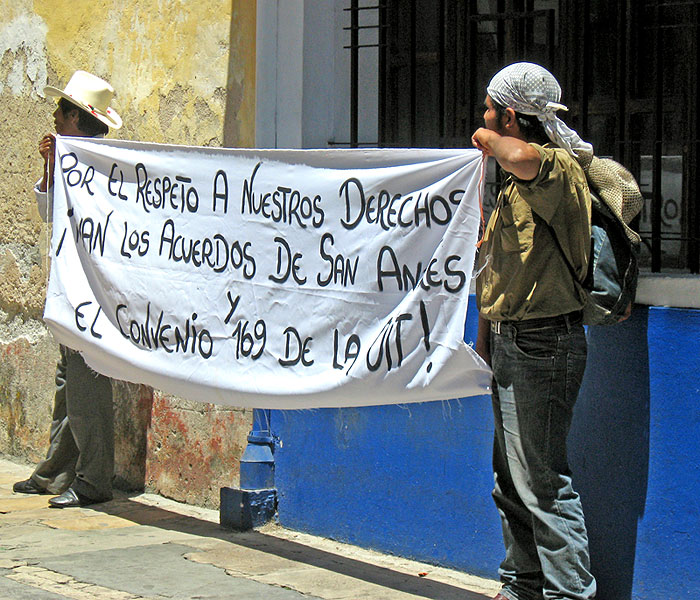

We conclude by mentioning a very important aspect of this strategy: starting with a global analysis to decide on specific objectives. This does not mean focusing on a particular injustice but rather understanding it as the product of the system that created it. In this example, they frame the struggle for fair electricity prices within the importance of realizing the San Andrés Accords (agreements on indigenous culture and rights, signed by the federal government and the Zapatista Army for National Liberation in 1996). In choosing a limited objective that is more readily accessible, it seeks to affect the larger system.

From disobedience to the questioning of an unjust system in itself

© SIPAZ

Civil disobedience finds its basis in an individual decision, though if it is maintained at this level, one must speak of conscientious objection. An example of such in Mexico would be the heated public debate that was had when, on 10 April 2010, a law was passed that requires cellular-phone users to register their numbers and chips with the National Registry of Telephone Users (Renaut). The State’s argument for the implementation of such a measure was to improve the country’s public security and to avoid extortion, kidnappings, and other crimes that are carried out by means of cellular phones. This generated a questioning in regard to the right to liberty and privacy, since, when one registers one’s phone, it is demanded that one provide his or her name, CURP (Unique Key for Population Registration), and home address. During this process, those who had not registered before the deadline were threatened with having their lines cut. After the deadline, however, some 17 million people had not registered their phones, some perhaps because they were unaware of the law, but others out of personal conviction. Indeed, a list consisting of the complete data of known political figures were circulated and people were invited to register their cellular using one of these names as a manner of questioning the violating nature of the request as well as the inutility of the process.

When conscientious objectors decide to unite themselves and attempt to formulate a joint strategy to effect change rather than merely denounce, this amounts to civil disobedience, as we saw in the previous example. If in a society governed by representative democracy, the citizenry is justified in not awaiting a change in government to change an unjust law—for the realization of justice is not to be delayed—there also exists another scenario to consider: when “it is no longer a question of opposing an unjust law in a democratic society but rather one of resisting an unjust power that intentionally violates the principles of democracy. In this case, civil disobedience can be converted into a peaceful insurrection of the citizenry that no longer seeks to change this or that law, but the power-system itself” (JM Muller). In this case, if the legitimacy of civil disobedience is rooted in the right of the people to resist injustice in a democratic system, the legitimacy of peaceful insurrection is rooted in the right to resist oppression when it is not democratic.

Peaceful insurrection is the present strategy of the Zapatista movement, and has been so for various years now. Following 12 days of war in 1994, the Zapatistas have respected the cease-fire. After seeing the closing-off of various democratic spaces for the airing of their grievances, and in light of the continued failure of the government to implement the San Andrés Accords, the Zapatistas have opted for constructing autonomy by a process of deeds. They have removed themselves from the perceived need to obey a power they consider to be unjust and illegitimate, and they continue constructing another proposal – based on the civil structure headed by their Good-Government Councils (Juntas de Buen Gobierno – JBGs). The JBGs are constituted of representatives of the Zapatista autonomous municipalities. Their members, male and female, hold rotational posts, and can be recalled at any moment if they are found not to respect the demand to “command while obeying,” the idea being that “the people command and the government obeys.”

The Zapatista proposal is more than an alternative approach for handling the problems of political representation in democracy. It is based on strong criticisms of the overall present exercise of power in Mexico and the world. The following metaphor reflects the Zapatista vision of power: “When the rebel comes across the Chair of Power, the rebel looks at it carefully, analyzes it, but instead of sitting on it goes for a nail-file and, with heroic patience, goes on filing down the legs until, as one knows, the legs become so weak that they break if anyone were to sit on the chair. This is expected to happen almost immediately” (communiqué, 2002).

On the other hand, the Other Campaign (a political initiative launched by the Zapatista movement at the national level in 2005) seeks to create conditions to restructure social relations, create a National Program of Struggle, and bring about a new political constitution, a new social pact that takes into account the demands of the Mexican people.

Regardless of whether we discuss democracy in Mexico (or in other countries) or the alternative proposals made by zapatismo, to dream of and construct actually-democratic forms is a permanent process that is often conflictive, one in which dissident voices should be seen as essential contributions to continue progressing and strengthening that which has already been achieved. The Zapatistas explain the “democracy” they are constructing in these terms: “It was always our path to see that the will of the others could be heard and be made common in the hearts of the men and women who command. The majority’s will is the path that he who commands should walk. If this walk is divorced from the people’s reason, the heart that commands should be changed for another who obeys. Thus was born our force in the mountains: he who commands obeys if he is true. He who obeys commands through the common heart of the true men and women. Another word came from afar so that this government be named, and that word named this path ‘democracy’ – this path, ours, that existed before words did” (communiqué, 1994).

… … … … … … …

From obedience to disobedience: The two virtues of the citizen (1)

The concept of democracy is before everything else a utopia to be constructed. The word comes from ancient Greek and is formed from the conjunction of “demos,” which can be translated as “people,” and “krátos,” which can be translated as “power” or “government.” The democratic ideal implies the construction of a form of social organization or government “of the people, by the people, and for the people” in which power and decision-making is to be shared by the totality of its members. It is based on a social pact in which is expressed the recognition of a series of agreement, rules, or laws, and the desire assumed by its members to live together according to those principles.

In practice, there exist many variations on the concept of democracy, although too often efforts have been made to impose a single model of understanding or implementation of such: the development of Northern societies that function according to indirect or representative democracy, has at times led to led to occulting modes of joint-living established by other peoples that operate by more direct fashions. In an ideal world marked by the co-responsibility of all citizens, mechanisms of participation and means of counter-power to confront representatives have been sought out when the need arises.

The democratic ideal implies equality of the distribution of power among all citizens. In large societies, the most-common model implies the election of representatives to whom citizens delegate their decision-making powers. One of the omnipresent risks of this model is that the voice of the citizen is counted only during time of election, while a basic characteristic of democracy is dialogue—the capacity to construct and deconstruct agreements so as to adapt to changes that can become necessary. An aspect that implies another type of risk has to do with the fact that these elections are often based on decisions of the majority, a process that can end up being anti-democratic when it affects the basic rights of minorities or individuals.

Beyond the challenges it brings, the implementation of democracy demands the obedience of citizens to laws that are passed to assist in defining means of living jointly. It is important to stress that obedience is not submission. “Submission” means “subordinate oneself to the desires of another.” It implies the suspension of questioning. In contrast, obedience comes from the Latin “oboedire” which means “to be attentive to” or “to take into account.” In this sense, obedience, which implies the exercise of free will, is a virtue of citizenship. (2)

If the “law of the majority” attempts to define what is just, it does not guarantee justice. A democratic government is not infallible; for the citizenry, justice ought to prevail in place of the law of the majority. “The law deserves the obedience of citizens insofar as it serves justice […]. But when the law supports or generates injustice, it deserves the rejection and disobedience of the citizens […]. He who submits himself to an unjust law makes himself responsible for injustice” (JM Muller). Hence, when democratic channels are closed and legal measures have been exhausted, citizens can demonstrate their support of the democratic ideal by engaging in acts of civil disobedience. If obedience is clearly a virtue of the citizen, disobedience vis-à-vis injustice is a complementary virtue of such.

Gandhi, a non-violent thinker and activist who helped bring about India’s independence by means of acts of civil disobedience, presents civil disobedience simultaneously as a right and a duty:

“No one has to cooperate in one’s own degeneration or enslavement… Civil disobedience is an unlimited right of all citizens. One cannot renounce it without renouncing one’s manhood [sic]. Democracy is not made for those who behave like sheep. In a democratic society, each individual jealously guards his or her freedom of thought and action. Each citizen makes him or her self responsible for everything done by government; he or she must grant it all her support insofar as it makes acceptable decisions. The day that those in power hurt the nation, each of its citizens has the obligation to withdraw support from it.“

One can examine the danger that civil disobedience represents for democracy, especially if one shares the sentiments of the majority. Considering the various cases of dictatorships in America and outside of it, history has shown that democracy can be more threatened by obedience to unjust laws and orders than by disobedience to such. Civil disobedience does not weaken democracy; instead, it protects and strengthens it, calling attention to its failures and appealing to a sense of justice that, from the conscience of the responsible citizen, can prevail over legality.

… … …

Notes:

- Jean-Marie Muller, Dictionnaire de la non-violence. Les Éditions du Relié, 2005, pp. 92 to 96 y 100 to 108.

- Maheu-Vaillant E. (ed.), L’autorité, pour une éducation non-violente, Ed. du MAN, 2010, p.89

- Jean-Marie Muller y Alain Refalo in the French magazine Alternatives Non-Violentes #142 “Eloge de la désobeissance civile. Les désobéisseurs au service du droit.”

- Communiqué 1 May, 2010