ANALYSIS: Serious challenges to Mexico regarding human rights

31/03/2010

ANALYSIS : Progress, stagnation or deterioration?

30/12/2010On 4 July elections were held for mayorships, state-congresses, and governors’ positions in 12 states of the Mexican Republic in addition to local-council and state-congresses elsewhere. The National Action Party (PAN, the right-wing party presently in power) and the Party of Democratic Revolution (PRD, considered less right-wing) had made a rare alliance to jointly oppose the advances being made by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and in fact did so in Oaxaca and Puebla, states historically considered to be PRI bastions. The elections were considered a “test for 2012,” the year of the next presidential elections, given that the PRI had established itself as a primary power following the 2009 national-congressional elections. Since then, it has been considered to have high chances of returning to the presidency in the forthcoming six-year term.

Both the PAN and PRI emphasized their victories on this electoral day. The PRI has argued that, of the 12 governorships in dispute, it won 9, in addition to the majorities of several state-congreses and mayorships. For its part, the PAN stressed its results in Puebla and Oaxaca, where an eighty-year period of PRI hegemony came to an end. The PRD itself lost several governorships and, in the three states in which its alliance with the PAN triumphed, it won no new representational-seats. For this reason some commentators agreed in highlighting the growing tendency toward bipartisan alternation (that is between, the PRI and the PAN), characterized by a lack of profound change in governmental policies. Nevertheless, the protests called for by the 2006 PRD presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) continue to be comprised of a significant number of citizens who are alienated by the present political situation. Their protests manifest a popular discontent that could make AMLO a relevant political agent in the next presidential elections.

One of the major focuses of attention within this electoral context has been Oaxaca. Amidst accusations of electoral crimes, investigations found a very close result between the candidate for the “United for Peace and Progress” alliance (PAN-PRD-Convergence-PT), Gabino Cué Monteagudo, and the representative for the PRI and the Green-Ecological Party of Mexico, Eviel Pérez Magaña. Oppositional voices had feared that the exiting governor, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz, would engage in fraud to keep the PRI in power. In any case, the victory of Cué Monteagudo was quickly established, and his rival Pérez Magaña accepted his defeat rapidly thereafter. The opposition also succeeded in taking the majority of seats in the state-congress.

In Chiapas, the elections for 118 mayorships and state-congress posts were held within a context marked by several violent incidents as well as purchasing of votes. During the time leading up to the elections, violent acts resulted in the death of two, the injuring of dozens, and the destruction of 15 houses and the burning of some 30 vehicles in Nachig, municipality of Zinacantán. Behind this conflict is found the dispute for the town mayorship. On election day, Juan José Díaz Solórzano, former mayor of the municipality, was detained on the charge of having bought votes for the mayoral candidate of the Green-Ecological Party of Mexico (PVEM), Sandra Luz Cruz Espinosa, as well as for the PRD-PAN alliance’s local-deputy candidate Antonio Morales Messner. On the same day, a presumed PRI militant was detained in San Juan Chamula, found carrying 400 electoral ballots marked in favor of this party. In this same municipality, residents of the community of Rancho Narváez held government functionaries for several hours, demanding that 8000 missing ballots be found. Furthermore, Francisco Girón Luna, president of the National Union of Autonomous Regional Campesino Organizatiassons (UNORCA), was assassinated that morning. He had no public charge, but he was associated with the PRD local authorities.

The “Unity for Chiapas” alliance (PAN-PRD-Convergence) took the mayorships of the state’s largest cities. Of the 118 minicipalities, it gained the majority in 55 mayorships, for a total of 517,421 votes. The PRI won 333,963 votes and ended up with 41 mayorships, taken either by their own representatives or those of the PVEM. None the less, little about the position of the elected candidates is revealed in electoral-number results, given that politicians in Chiapas have changed party affiliation on several occasions, if the possibility of being a candidate in their own party had been closed to them.

The struggle against organized crime – daily bread

A subject that has been omnipresent since nearly the very beginning of the present six-year presidential term, the so-called “war on drugs” launched by President Felipe Calderón that involves conflicts between authorities and organized crime, or among opposing groups within the same organization, continues to dominate the news media. Arturo Chávez Chávez, Mexico’s Attorney General, asserted on 16 July that 24,826 Mexicans had died since 2006, while on 3 August in the second session of the Dialogue for Security organized by the federal government, Guillermo Valdés, director of the Center for Invesigation and National Security (CISEN), admitted that the death-toll now amounted to 28,000. This discrepancy in statistics—not a minor one—should be questioned as should the means by which such numbers are recorded by the governmental agencies involved in this battle.

In light of the violence that Mexico has suffered since the beginning of this “war,” several events that have come about in recent months has provoked debate within the media. The explosion of a car-bomb in Ciudad Juárez on 15 July—blamed by authorities on organized crime—provoked a discussion regarding whether Mexico/Mexican society was ready to confront a new strategy employed by “narcoterrorism.” Some days later William Weschler, sub-secretary of the Pentagon, confirmed that the U.S. Army was training Mexican military units in tactics for dealing with narcoterrorism, including irregular war methods—that is, counter-insurgency. In the view of the Obama administration, it seems, Mexico in its struggle against drug-cartels is facing similar threats to those that U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan also face.

It seems strange, then, that Mexico’s northern neighbor has not yet come up with mechanisms to effectively measure the impact of the aid it has given Mexico via the Mérida Initiative, as revealed in a report made by the Governmental Accounting Office (GAO),which is the investigative body of the U.S. Congress. The report criticizes the lack of said mechanisms to evaluate results and also asserts that the U.S. should work to reduce the flow of illicit money and arms-trafficking to Mexico with the intent of reducing the level of violence experienced there. It also stresses the need to decrease the demand for drugs emanating from the U.S. to begin with.

With regard to abuses committed by military units, Mexico’s Secretary of National Defense (Sedena) released a report that details the number of complaints received and of recommendations made by the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH):Both have increased significantly during Calderón’s term. Although human-rights organizations recognize that Sedena’s making-public such information constitutes progress, they have also noted that the conclusions excluded mention of the serious limitations the use of military courts imply in such cases.

The justice system, influencing policy

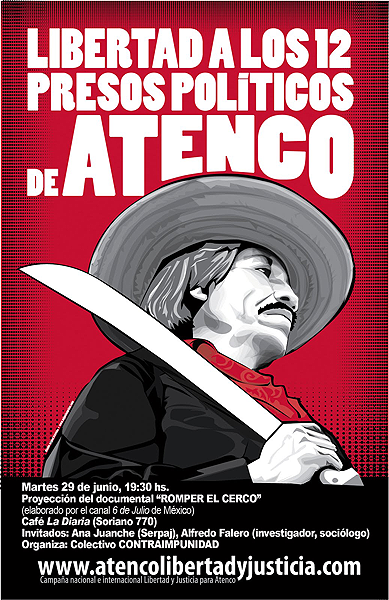

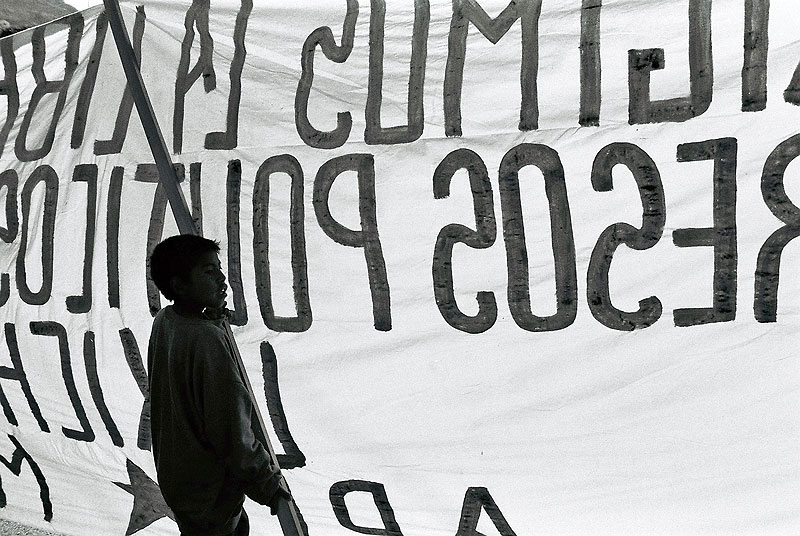

After four years, a lengthy stage of political struggle and lobbying on the behalf of the members of the Front of Peoples in Defense of the Land (FPDT) from San Salvador Atenco has ended with the release of the remaining 12 prisoners from this organization held for a conflict involving municipal, state, and federal police on 3 and 4 May 2006. On 30 June, the SCJN repudiated the sentences holding the 12, arguing that the State Attorney General’s Office of the state of Mexico (PGJEM) had used illicit evidence, and also had used false premises when the accusations began.

It is to be imagined that the pressure exercised by those from Atenco and those who have engaged in solidarity with them these four years influenced the court’s decision in this sense. Their detention and processing were marked by a context during which the federal government in the six-year term of Vicente Fox (2000-2006) presented as one of its grand projects the construction of a new airport-capital in San Salvador Atenco, which was successfully opposed in 2002 by social activists defending their land. From this perspective, the police operation of 2006 was understood by many as an act of vengeance on the part of the state and federal governments.

In addition, the SCJN endorsed the liquidation of the parastatal firm Light and Power of the Center (LyFC), an act that had been had been decreed by President Felipe Calderón on 10 October 2009. The court declared that the federal executive was authorized to make this type of decision, thus rejecting the principle argument advanced by the defense of the Mexican Union of Electricians (SME). The decision, which in juridical terms seems to be legitimate, closes the chapter of the legal struggle engaged in by the SME since last October. It represents a serious blow to the fight to save the employment of its 44,000 workers. Regardless, this does not end with the questioning of a highly political decision, which in effect would do away with one of the unions that has been highly involved in the oppositional social movement that has opposed both PRI and PAN governments.

Oaxaca, flowering of violence

Since the aggression visited on the caravan that was travelling to San Juan Copala on 27 April—an attack that killed Bety Cariño and the Finnish observer Jyri Jaakkola (see SIPAZ’s Special Bulletin and earlier report)—conflictivity in the Triqui region has been covered constantly by the media. On 20 May, Timoteo Alejandro Ramírez, leader of the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle-Independent (MULT-I), was killed together with his wife, Cleriberta Castro, in an act that MULT-I blamed on its rival, the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle (MULT), from which Ramírez had left in 2006 to form MULT-I. Alejandro Ramírez was one of the founding members of the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala, which since the end of 2009 has suffered a precarious humanitarian situation due to an encirclement said to be maintained by the Union for Social Welfare in the Triqui Region (Ubisort), which has been claimed to be a paramilitary group linked to the state government. Ubisort inhibited the entrance of the “Bety Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola” caravan that on 8 June brought more than 300 people carrying goods to the imprisoned populace of San Juan Copala. Previously, the government of Ulises Ruiz Ortiz had warned that there existed a “lack of conditions” for the entrance of the caravan to Copala, given that the three groups with presence in the region are said to be armed. The caravan could not arrive to its destination because Ubisort blocked the road, demonstrating that the government of Ruiz Ortiz cannot—it seems—guarantee the state of right in the totality of the state, or—as some activists claim—is entirely complicit with the violence generated by Ubisort, if it does not direct it.

Chiapas – continuing tendencies

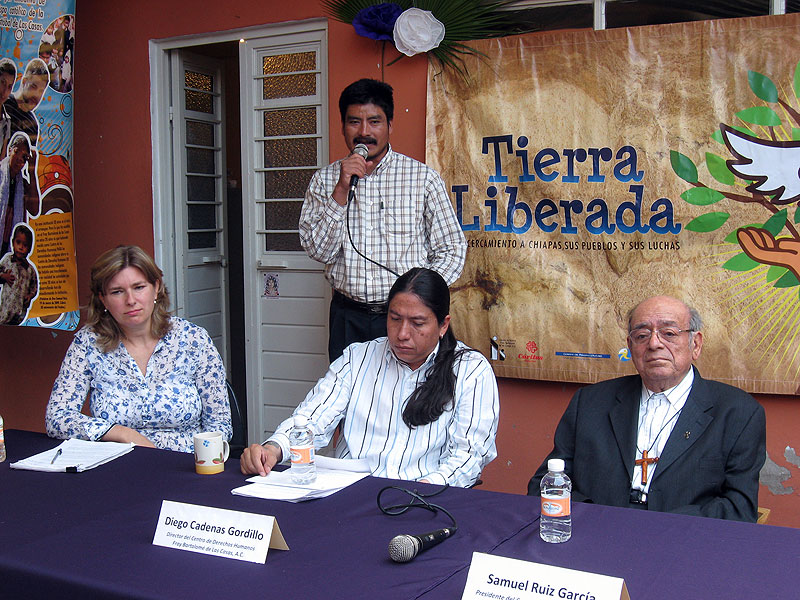

On 27 May, the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC) presented its 2009 annual report. The report speaks of the “ambitions of firms to extensively exploit the natural resources of Chiapas, particularly those located in territories belonging to indigenous peoples, which have caused several communities to engage in actions to defend their right to their lands. Other important subjects examined by this Report are the criminalization of social and civil organizations that [oppose] the pillaging and destruction of the environment and the lack of respect for the rights of peoples, as well as the systematic violence directed against women as a goal to be gained through war, the continuation of counter-insurgency strategies and the historical memory that the peoples construct in light of the violence and lack of justice perpetuated by the Mexican State.”

Meanwhile in Chiapas the state government continues to present itself as an administration complying with the U.N. Millennium Development Goals, and communal conflicts whose origins could be said to lie in the application of governmental economic projects or in the divisions generated by means of political differences between groups in resistance and those close to official policy continue unabated.

One example of such conflictivity was seen on 21 June in the community of El Pozo, in San Juan Cancun, where PRI and PRD militants threatened to cut the water and light to a group of Zapatistas, resulting in the death of one on the official side. In accordance with the communiqué of the Good-Government Council (JBG) of Oventic, “the rural agent and PRI and PRD members demand that our comrade support-bases pay for the services of light, knowing well that they are in resistance and are struggling for a just cause, to construct their autonomy.” According to the Zapatista authorities, “The happenings in El Pozo, as can be seen clearly, was not a conflict as depicted in the media, nor was it an aggression provoked by Zapatista support-bases, as it claimed. In light of the aggression, our comrades had to defend themselves somehow, using violence as a last resort to defend themselves against the aggression provoked by PRI and PRD members in El Pozo, seeing as they did their comrades being beaten and hit over the head, others being dragged through the streets.” It should be mentioned that the first half of this year has seen five cases in which Zapatista authorities denounce communal conflicts, a sign of the local deepening in the mark of the ongoing unresolved armed conflict.

Although in Chiapas there is no omnipresence of organized crime as in the north of the Republic, it one can notice an increased range of social protest against the policies of the state government, as is seen often in the news. These protests have had a strong presence in the local and national media. Giving space to such dissident voices can be uncomfortable for authorities, as seen in the case of journalists Isaín Mandujano and Ángeles Mariscal, correspondents in the state of Chiapas for the magazine Proceso and the daily newspaper La Jornada, respectively, who on 23 July denounced a campaign of organized slander against them so as to disqualify their work—a campaign, they say, in which media dependent upon the state government of Chiapas has participated actively.

An affair over which the government has kept quiet, while on other occasions strongly promoting its project of Sustainable Rural Cities (CRS), is the possible construction of one of these in the municipality of San Pedro Chenalhó. The social civil organization Las Abejas, in a 22 July communiqué, expressed its rejection of this project, claiming that “the project of the rural cities—officially denied by the bad state and municipal governments—is known also to be in preparation in Chenalhó. Many think this to be development, but many others don’t want this mega project. “We are not the only ones who know that this project is part of the Mesoamerica Project, formerly known as Plan Puebla Panamá.” The parish of San Pedro Chenalhó expressed itself similarly on 8 August, asserting that “It worries us that this project of the rural cities be imposed rather than consulted; if consultation is made, it is based on lies and omissions.” The first rural city constructed in the state was Nuevo Juan del Grijalva, and the second one is being built in Santiago el Pinar, municipality located between Chenalhó and San Andrés.

© Autonomous Regional Council of the Coastal Zone of Chiapas

Militarization, a tendency at the national and local level – in the latter since the Zapatista uprising – continues to represent an element of intimidation in organizational processes. Although the phenomena of military incursions has diminished in recent months, it has not ceased altogether. On 22 July, the Emiliano Zapata Campesina Organization-Carranza Region (OCEZ-RC), denounced that the day before a vehicle of the Secretary of the Navy of Mexico arrived at one of its communities. The vehicle contained some 40 camouflaged soldiers directed by a commander who did not identify himself. Facing questions regarding the unit’s motive, the commander asserted that he had received federal orders to patrol the area, indicating that constant patrols would be carried out by federal order.

The defense of human rights can result in the criminalization of this type of work, when it implies the accompaniment of social processes whose dissent can prove inconvenient for the authorities. Such is the case of Nataniel Hernández Núñez, director of the Digna Ochoa Center for Human Rights in the city of Tonalá, who faces an investigation for the crime of “attacks on communication media” following his participation as a human-rights observer in a protest of the Regional Autonomous Council of the Coastal Zone in April.