ANALYSIS: Mexico – human rights and security, an impossible puzzle?

30/04/2009

ANALYSIS: A Serious deterioration of the human rights situation in Chiapas and Mexico

30/11/2009Note:

Due to the request made by some members of the Community of Faith, we decided to let the quotations anonymous in the following article.

Journey of the “Community of faith”: Reflection and action on a changing reality

“Faith does not exist without history. Faith is the result of living – of both the journey and the long road taken. The year 1992 marked 500 years of indigenous resistance within an oppressive system. The journey of the “Community of faith” (Pueblo Creyente) is born out of a search for freedom within the burden of oppression. We may not have freedom yet, but we can’t stop working towards it. The time we spend on this path brings us to a better place, a new place where we can see the past and better understand the future. We can’t abandon this road. It is ours to conquer.“

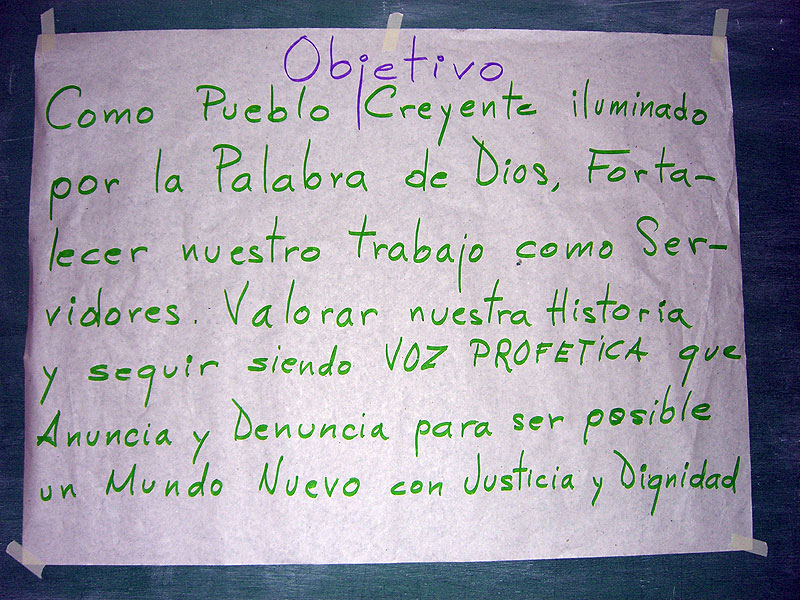

The 18th meeting of the “Community of faith” was held in San Cristóbal de Las Casas from July 1st to 3rd, 2009. The goal of the gathering was to record the experiences and events of the “Community of faith” throughout its history. It was also a good opportunity to become more familiar with this multi-faceted movement and the ways it has sought to analyze and adapt to changing realities.

Where did the journey of the “Community of faith” begin?

Every story begins with an unavoidable step forward – at times well thought-out, at times forced by the context of the times. When the parish priest of Simojovel, Father Joel Padrón, was jailed in 1991 members of the eight regions of the San Cristóbal de Las Casas diocese went on a pilgrimage demanding his release. The pilgrimage became a march to Tuxtla Gutierrez, the capital of Chiapas, and after 49 days in prison Father Padrón was released because of pressure from the people. In this way the movement of the “Community of faith” has roots similar to political movements except it remains within the diocese thanks to a combination of faith and politics, or “faith-politics” (without the “and“). But to gain a better understanding of this first step forward it’s important to go into more detail about the history of the people and the Church in Chiapas.

During the 1970’s, the Catholic Church established liberation and independence as important priorities, an orientation that originated with the Second Vatican Council and the General Conference of the Latin American Episcopate (CELAM) held in 1968 in Medellín. Meanwhile, the indigenous church set the goal of being “incarnate in indigenous cultures, with the old word of Indian theology being the source of the Word of God” and as the legitimate “option for the poor” who were “the main actors for profound changes in Latin America”. Samuel Ruíz García, Bishop of the San Cristóbal de Las Casas diocese from 1960 to 2000, recognized this as an “historic act on behalf of the Church”. His diocese became fertile ground for the Word of God and the changing realities of the times gave life to a “cornfield” (milpa) of dialogue and reflection rooted in the methodology of liberation theology, to “see-think-act”.

In 1974, after nine months of preparation, an Indigenous Congress took place in San Cristóbal de Las Casas. The conference commemorated both the incorporation of Chiapas as a state 150 years before, as well as the 500-year anniversary of the birth of Bartolomé de Las Casas, the first bishop in the region. The Congress took place in the four main indigenous languages of the region (tseltal, tsotsil, tojolabal and ch’ol) and tackled themes such as land, commerce, education and health. The extreme economic, political and social marginalization of the indigenous people of Chiapas was denounced and a plan with “fair guidelines that was organic and systematic” was outlined to overcome that marginalization.

After 1974, the villages continued to analyze the reality of their situations using “the signs of the time” to lay the foundation for a work in progress. From 1975 on they held annual diocesan meetings. Almost 20 years later the pastoral letter “In This Hour of Grace” (November 1993) posed the following question: “Instead of waiting for social structures to change because of the desperation of those who have been historically oppressed, why not start on a different path?” The document marked a seismic shift for social movements that were until then underground. Events arising out of these social movements, such as the Zapatista uprising in 1994 and the San Andres Accord in 1996, are now both part of history and the present.

In 1991, the head organizer of the diocesan meetings consulted with delegates of the pastoral teams about how best to proceed. It was suggested that the people who made up each diocese be consulted, and in order to do this representatives from each pastoral region were invited to participate. In total, 36 advisors participated in this pre-assembly, which then became a semi-permanent meeting. The movement of the “Community of faith” was born from this small group.

Father Joel Padrón was jailed on September 18th, 1991. He was accused of desecration, injury, robbery, making threats, provocation, defending a crime, associating with the intention to commit a crime, gangsterism, conspiracy, and the carrying of combat weapons. The state government called him a “guerilla priest” and “promoter of subversive acts” while landowners accused him of instigating land invasions. But because of the work of the diocese in previous decades many people rose up to say “your prison is our prison.” Eighteen-thousand members of the “Community of faith”, most of them indigenous, marched from San Cristóbal de Las Casas to Tuxtla Gutierrez demanding Padrón’s release through fasting and prayer.

Present day structure

In the words of Don Samuel Ruiz, the movement of the “Community of faith” is part of a “critical analyses of reality with a dimension that incorporates the reign of God within history. The implication is a societal transformation that begins with the elimination of severe oppression.” The movement of the “Community of faith” does not come from any other part of the world, nor exist in any other part of the world – its roots are in the history of the diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Today the movement of the “Community of faith” has been consolidated and its structural base is spread out among the different areas of the San Cristóbal diocese. In spite of this, the Assembly of the “Community of faith” is only one of many work committees that exist in the diocese. Some other examples are Indian theology, Ecclesiastic Base Communities, catechism, deacons, health, youth pastors, women’s issues, human rights, etc…

In every region the committee leaders hold an assembly to reflect locally on “an analysis of their reality within the framework of the Word of God” to find “alternatives that are in harmony with peace, and both societal life and the life of the Church.” Previously they would meet four time a year in San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Each meeting would be organized into committees dedicated to: analysis, the writing of a newsletter called “The Truth Will Set Us Free”, the liturgy, logistics, etc…

Afterwards a meeting would be held in each region, sometimes as part of a pastoral team meeting. “For example, in the Selva region, a catechism meeting is held the day after the assembly of the “Community of faith”. There are about 200 catechists and from there it is passed down to other community members. This really has an effect the communities. Decisions are taken using this same method.” The strength of the process lies in the back and forth of information. It’s a participative model and a collective experience that allows for ideas to be fully endorsement when going from reflection to action.

One of the priests attending the most recent Assembly underlined the fact that “the pastoral team is not in charge – instead they are accompanied by the people. It’s about reflection.” Another person emphasized that the “movement of the “Community of faith” belongs to no one. It’s the rising up of a transformative consciousness that is inspired by the Word of God, history and suffering. It’s difficult to place it within partisan logic, social or organizational movements. The space transcends many elements. It has its own life without fixed political meaning; otherwise it would have to be in the service of that meaning.”

During the past 18 years, the tseltal, tsotsil, ch’ol, tojolabal and mestizo have walked this path saying, “We are the diocese.” They want to integrate their agenda within the structure of the Church without losing their identity, and with the capacity to effect change on a large scale. Since 2000, the movement of the “Community of faith” has been part of the Synod and the internal structure of the Church while maintaining its unique roots within the indigenous church and the church of the poor.

Today’s challenges

“It’s impossible to talk about the movement of the “Community of faith” without feeling its presence over time in the fight between two alternatives: death (neoliberalism) and life. But it’s becoming more and more difficult to build an alternative for the people.” Up until 1960 Chiapas was “terra incognita” (Andres Aubry) – known by very few outside of its borders. It was a feudal world under the control of a few families who shared power, called a Province “on the outskirts”. When Samuel Ruiz arrived in Chiapas, the ranch owners used the indigenous people as laborers in a system characterized as semi-slavery.

Much has changed since then but at the same time, little has changed. “The material world needs victims to survive. That’s why it looks for slaves. The material world can repress heart and soul, and change our minds. Our main task is to fight the slavery that represses our souls, hearts and minds.”

Today, the movement of the “Community of faith” stubbornly continues to look for ways to change an oppressive reality and become agents of change, as well as political, social and ideological decolonizers. The “Community of faith” dream of a different world and work to make it a reality. As villages and people who are free and are agents of change within that freedom, they choose a world where they take a firm stand within Salvation’s plan. “We can choose between life or eternal death; between God and the idols of power and money; between freedom and oppression; between living and building a community, or submerging ourselves in consumerism.” (In This Hour of Grace)

In this sense, “The “Community of faith” haven’t stopped being a political exercise and a movement. The Council (Synod) defines the movement of the “Community of faith” as a ‘rising up’. There is a very clear consciousness of fighting for justice, human rights, reconciliation and peace in a Church that is indigenous, and in the service of others and freedom.”

Between 1991 and 2008 the “Community of faith” started to undertake pilgrimages and visits to jails – not only to spend time with “their own” but also with other prisoners. The “Community of faith” demanded their release. Particularly noteworthy is the continuity the movement has shown in this respect over the years. Zacario Hernández Hernández was the first person to go on a hunger strike (in March 2008) and when he was released from prison he said the words of San Pablo sustained him during the strike: “When I am weak I am strong.”

The “Community of faith” also seeks to go beyond the division and fragmentation that has occurred in the social fabric, which is for the most part the consequence of years of slowly wearing down people with low level war after the Zapatista uprising.

The movement of the “Community of faith” is in a deep period of recovery, restoration and rediscovery of its past, mainly as Mayan people (even though the Council talks about mestizos and indigenous.) One regional representative says the movement is in a period of “reclaiming the past that has been lost to the point of bringing back the practice of praying by wells or in the fields after the corn has been planted. This practice is something that had been lost in many places, and less so in others.” The representative said an important aspect is listening to the elders: “It’s important not to leave behind the elders in the community because they are wise.” Also important are ways to reclaim self-government and to strengthen self-government following the teachings of these same elders, the great-great grandparents.

Dreaming of the future

“Concrete situations need to be converted into struggle; otherwise our lives are at stake. It’s a constant challenge. A pilgrimage is something political in this context – it’s expressing oneself politically. The question that we’re asking ourselves is how to maintain this strength and to see things through. There are issues affecting our land and territory – like organic food and transgenic seeds – that are already in the works. The future is getting closer.”

During the 18th Assembly the future could be seen from the same hill that also enables us to look at the past. People emphasized the following: “We want to denounce unjust relationships, systems of domination, that which destroys nature, and be free women and men”; “To act now is to be a man of the future, to live and acknowledge its importance. My life experience is on the path to the future”; “In the future we need to be is plural, cooperative, open and approachable, tolerant and respectful. Similarity isn’t necessary but respect and understanding is.”

They say that the strength of the movement of the “Community of faith” is in the fact that although feeling injustice is not the same as being a victim, the movement of the “Community of faith” knows both of these experiences. It knows how to be an exposed nerve that connects with suffering and has the ability to strengthen people with its faith. “They are people who have a lot of conviction, without fear of pain or heat.” The same person says faith is in resistance. “You have to resist and fight what they want to destroy of the people.”

The movement of the “Community of faith” is both a historical and present-day witness and protagonist of “living faith.” It’s not necessarily based on “visible actions or occupations of city halls” but on more profound change. “It’s something inside oneself. A prayer or way of talking that makes you sensitive to this moment in life. It tries to reclaim that, to change automatic and social prayer which to a certain point is only asking, asking for a meeting in the other world.”