2013

31/01/2014

In Focus: Preaudience of the People’s Permanent Tribunal: “Meeting for Justice and Truth”

21/02/2014At the beginning of 2013, several analysts used the expression “the Mexican moment” in reference to the expectations generated by the change in federal administration. The relevance of this phrase, however, continues to be questioned. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN), came to celebrate the approval of his structural reforms, the main focus of the first year of his administration. He did not expect that the president of the Forum, Klaus Schwab, would raise the question of insecurity in Mexico so insistently. Alongside the advance of the reforms, the year 2013 was characterized by the emergence of self-defense groups.

© SIPAZ

Attention has been focused on the state of Michoacán, where confrontations between organized civil self-defense groups and the Knights Templar cartel have intensified. Some observers accuse the self-defense groups of arising from a plan designed by the Presidency, while others accuse them of supporting the “New Generation” Jalisco cartel. What is clear is that in 2013 insecurity certainly worsened in Mexico: according to the National System for Public Security, 12,715 murders were perpetrated in the state of Michoacán between 2007 and September 2013. The self-defense groups today maintain an armed presence in 47 of the 113 municipalities, according to the Michoacán state government. Their leaders estimate that the groups have over 10,000 members in total. The battles between the conflicting groups take place in regions characterized by marginalization, insecurity, and absence or lack of response on the part of the authorities. In a context that some media have begun to term a “civil war,” the federal government sent 8,000 federal police and soldiers to take control of the municipalities in which self-defense groups had emerged. On 27 January an agreement was signed to legalize them as “rural defense corps,” and there was an announced investment of more than 45 billion pesos for social programs in the state. The context nonetheless continues to be explosive, and it could spread to other states.

In general terms, EPN’s strategy with regard to security has been challenged for being a mere prolongation of the strategy implemented previously by his predecessor, Felipe Calderón, despite the dramatic casualties which resulted from the application of the PAN administration’s approach. At present, official statistics (which have been challenged by many media) report a reduction in murders but an increase in kidnappings and extortion. The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) has indicated that during the first year of EPN’s government, very little progress has been seen in terms of security, and the number of human rights violations continues apace,with total impunity. For its part, Human Rights Watch has affirmed that the supposed change in this area with the new administration has been purely “rhetorical.”

Other sources of skepticism about the “Mexican Moment”

The perception of a “Mexican moment” has changed not only in light of the persistence of security problems but also in macroeconomic terms: the forecast for economic growth in 2013 (3.5%) was one-third of what was expected. While firms and foreign investors welcomed the legislative reforms that were passed, particularly the forcible opening of the petroleum sector, it remains to be seen how these will be implemented in concrete terms.

In the country, these legislative changes have generated challenges and opposition mobilizations, with limited results. In the case of the labor reform, a year after its passing, formal employment has not increased: in 2012, more than 832,000 jobs were created, but only a little over 590,000 in 2013. The implementation of the educational reform was marked by delays in the census of schools and teachers, in addition to various waiver agreements, while new protests were announced that will be “even more radical and massive” than those seen in 2013, according to teachers’ claims.

The fiscal reform has been challenged by businesspeople as well as by the general public due to new tax requirements and inflation, in addition to being accompanied by an increase in gasoline prices at the beginning of 2014. Despite the fact that the social pressures exercised against the educational reforms led to the cancellation of the planned value-added tax on foods and medicines, analysts have observed a generalized impoverishment of the population and a destruction of the middle class. There is fear that the electoral-political reforms have created a new bureaucratic apparatus that could be even less effective than its predecessor in terms of supervising public spending and ensuring fair elections. These reforms will allow for the immediate re-election of legislators despite the risks this would imply: that is, that political immunity could be converted into impunity.

Lastly, the approval of the energy reform, which took place in a session protected by riot police against protesters, completes the process of what some consider the handing over of the energy sector to private capital. Because of this reform, the “Pact for Mexico” among the three principal political forces of the country (the Institutional Revolutionary Party [PRI], the National Action Party [PAN], and the Party of the Democratic Revolution [PRD]) collapsed. On 28 November, the PRD announced its departure from the Pact, denouncing a “secret little pact” made between the PAN and PRI.

Dispersion of the institutional left and criminalization of social movements

The institutional left finds itself at a moment of extreme weakness. Former presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) decided to found his own political party from the social base of the Movement for National Regeneration (MORENA). His absence during the debate on the energy reform due to a heart attack demonstrated the great dependence placed on his leadership. The adherence of the PRD to the Pact for Mexico caused more internal divisions. It is unclear if its departure from the Pact will be able to reverse this tendency. None of the groups that acted isolation and with little capacity for mobilization succeeded in halting the approval of the energy reform. However, a possibility is seen in the chance for a referendum on this reform.

From the social movements, in February there was held a Popular Congress in Mexico City. It was convened by intellectuals, artists, and activists to promote a unifying process that could revoke the approved reforms. 2,652 persons participated as “popular representatives” completely independent of all political parties, government institutions, or business groups. The Popular Congress approved an initiative to revoke the energy reform and called for peaceful actions of civil resistance in March.

These mobilizations have taken place within a context of systematic criminalization of social protest. Amnesty International has questioned the “increase in abuses committed against protesters by police forces.” For its part, the People’s Permanent Tribunal (TPP) released a judgment in its chapter on “Mexico: The repression of social movements,” which offers a general picture of governments that have “converted private and specific interests into the general interest and employed brutality and violence against all those who have been bold enough to protest to demand better living conditions and the enjoyment of rights by all.” The TPP denounced the “judicialization of the social conflicts and the renunciation of dialogue, political processes, the observance of human rights, the rule of law, and democracy.”

Beyond this, the lifeless body of Veracruz journalist Gregorio Jiménez de la Cruz, who had been kidnapped on 5 February, was found just days later. It should be noted that, since the PRI governor’s taking power in 2011, ten journalists have been murdered in Veracruz, with at least three disappeared. With 87 journalists killed since 2000, according to the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH), Mexico is the most dangerous country of Latin America in which to exercise this profession.

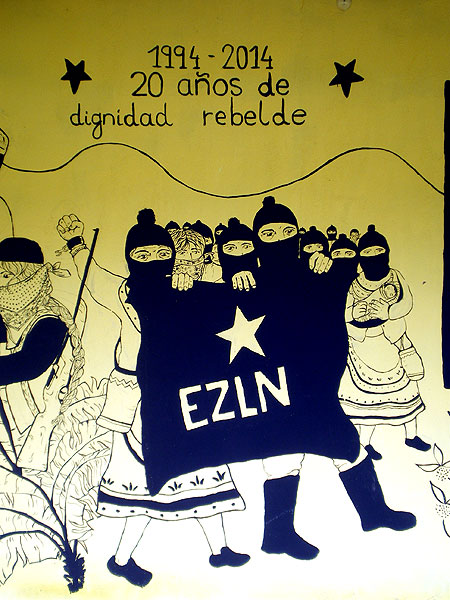

Chiapas: Twenty years after the Zapatista insurrection

On 1 January 2014, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) celebrated 20 years since its armed uprising to demand land, food, work, education, housing, justice, and equality for indigenous peoples. The EZLN shared its successes with two sessions of the Escuelita (“Little School”) held in December and January, attended by more than 4,000 persons, both national and international.

Just before the New Year, Subcomandante Marcos had released a new communiqué entitled “Rewind 1.” In a long postscript, Marcos challenged the commercial media and a number of articles that had been published on the eve of the anniversary of the armed uprising: “if the conditions of the Zapatista indigenous communities are the same as they were 20 years ago and no living conditions have improved, why is the EZLN – as it did in 1994 for the commercial media — opening up its escuelita so that people from below can see it and get to know it directly, without intermediaries?” In another communiqué, Marcos criticized the structural reforms, particularly with regards to energy and education. In a postscript, he criticized the wastefulness of promotional media campaigns by the present Chiapas state governor, Manuel Velasco Coello, calling them “ridiculous” and “illegal,”and an attempt to hide “misery, the paramilitaries, and crime rates in the main Chiapas cities” from tourists. It should be noted that Velasco’s campaign provoked the PAN to present a complaint against the governor over undue publicity.

The authorities sent messages of goodwill in the run-up to the anniversary of the insurrection. In December, Manuel Velasco presented his first governmental report. He recognized that the debts owed by the Chiapas state governments to indigenous communities have yet to be resolved. “I hereby repeat that my administration will maintain its commitment to respecting Zapatismo and to resolving conflicts peacefully.” At the end of December, in addition, several prisoners were released. Finally, the commissioner for Dialogue with the Indigenous Peoples of Mexico, Jaime Martínez Veloz, reported that for February “a hugely important initiative” could be ready that would seek to revisit the San Andrés Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture signed by the EZLN and the federal government in 1996, and would incorporate new national and international laws in this area.

Impunity and prolongation of counter-insurgency strategy

Nonetheless, there have been several denunciations that illustrate the prolongation of a counter-insurgency strategy continuing to the present. The Morelia Good Government Council denounced that on 30 January, some 300 members of the Democratic Independent Center of Agricultural Workers and Campesinos (CIOAC) severely assaulted Zapatista support base members in the 10th of April ejido, belonging to the 17th of November autonomous municipality. The Zapatistas requested help at the San Carlos hospital in Altamirano, but the aggressors detained the rescuers for two hours, stripped and assaulted the nuns in the vehicle, and seized the ambulance and a truck.

Impunity has been an omnipresent subject on the civil agenda. In December in Susuclumil, Tila municipality, there was for a preliminary hearing of the Mexico chapter of the People’s Permanent Tribunal (TPP), part of the “Focus on Dirty War – violence, impunity, and lack of access to justice.” Relatives of victims, survivors, and those displaced from the Northern Zone and Highlands of Chiapas presented their testimony regarding the “victims of the counterinsurgency and extermination strategies set forth in the Plan for Chiapas Campaign 94 which was implemented by the Mexican government following the insurrection of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in 1994.”

In Chenalhó, displacement continues to be an ongoing problem. On 17 January, 98 persons from the Puebla Colony who have been displaced for more than 4 months returned to their community to harvest their coffee crop. These families had fled the Puebla ejido due to the wave of death threats and aggressions stemming from a conflict over the possession of land where a Catholic chapel was located. On 7 February, the displaced families returned to Acteal, where they have taken refuge since August 2013. They explained that “We would like to believe that the visit of Governor Manuel Velasco is a reflection of his will to resolve the problem, but, as with President Enrique Peña Nieto in Michoacán, it is not enough to have himself photographed and make promises to resolve problems. As long as they try to solve everything with promises of aid but justice is not done, there can be no solution.”

Land and Territory: Conflicts

With regard to social conflicts, the question of “land, territory, and natural resources” continues to be the basis of numerous mobilizations and demands. In November, a confrontation between maize producers from the region of Venustiano Carranza and police left several police trucks burned, 10 officers injured, and two campesinos arrested. Human rights organizations denounced that the Chiapas state government continues to practice repression instead of engaging in dialogue with the legitimate demands of social groups. In December, 56 communities, ejidos, and organizations from eight municipalities in the Sierra marched in Tapachula to declare their territories free of mining and hydroelectric projects. In February, representatives from Los Llanos, San Cristóbal de Las Casas municipality, and the San José El Porvenir community, Huixtán municipality, declared their opposition to the passage of the planned highway between San Cristóbal and Palenque through their communities. For his part, Eduardo Ramírez Aguilar, secretary of governance of Chiapas, declared that there will be “no retreat” for the project of constructing the highway between San Cristóbal and Palenque. He nonetheless recognized that “we have a problem with a kilometer in Los Llanos and 14 in Huixtán.”

In observance of the 40 years since the Indigenous Congress of 1974, in January in San Cristóbal de las Casas the Pastoral Diocene Mother Earth Conference was held, which echoed many of the denunciations regarding land and territory made throughout the state. Among other agreements, participants at the Congress decided to block mining operations (which continue to advance, for example in Chicomuselo) and government policies that negatively affect the interests of communities.

Guerrero: State of high risk for human rights defenders

Among the most recent cases, on 16 November in Atoyac de Álvarez, Costa Grande, two campesino leaders of the El Paraíso community were murdered. The events took place a day before the announcement of the creation of a communal police in the community. On 28 January, two members of the Truth Commission (Comverdad, which has the objective of issuing recommendations for the justice system regarding those affected by the Dirty War of the 1960s and 1970s), were subjected to an attack on the federal highway between Iguala and Chilpancingo. That same day, two members of the Decade against Impunity Solidarity Network were intimidated just a few days before the visit they were planning to Guerrero as part of a Civil Observation Mission “A Light against Impunity” that seeks to document the violations of the human rights of social activists in the state.

Another form of harassment is seen in criminalization. In January, the newspage of Milenio.com published an article that made reference to intelligence reports on Guerrero. The article alleges that “the social groups that were very active in the state in 2013 (such as the teachers’ movements and the communal police) were advised and infiltrated by guerrilla movements or members of insurgent groups that work in the region.” In response, the Collective against Torture and Impunity (CCTI) clarified to Milenio that it has no relationship or tie with any guerrilla groups, whether state or national, and it stressed that the published article threatens the physical and psychological integrity of its members.

In January, civil and parish organizations denounced that “one year after the communities and peoples of the Costa Chica and central regions of the state of Guerrero organized themselves to re-establish security and peace in their communities, they now face harassment, intimidation, and abuse of authority on the part of the Mexican Army and the federal and state police.” They affirmed that “in just one day 7 military checkpoints were installed” in addition to those already existing, and these “military checkpoints are not allowing the movement of civilians.”

In addition, the demand for basic grains for communities victimized by the storms that hit the Mountain region of Guerrero in September 2013 has still received no response. A working meeting with authorities was agreed to after communities carried out a large mobilization in Tlapa de Comonfort in February, amidst the lack of attention from the authorities who unilaterally cut off dialogue with the Council of Victimized Communities since the end of 2013. Despite the fact that the federal government claims the situation in the Mountain region is resolved, the looming food crisis is no mere invention.

In a decisive step in the struggle for justice, the Federal Attorney General’s Office arrested four soldiers who in 2002 presumably participated in the sexual attacks against the indigenous women Valentina Rosendo Cantú and Inés Fernández Ortega. In both cases, the Mexican State was found responsible by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2010.

© SIPAZ

In other news, in January, the Guerrero local congress approved a law to prevent, sanction, and eradicate torture in the state. The Global Organization against Torture, however, questioned the fact that the law does not meet the standards of established international law on the matter. It also lamented that the process had not been preceded by a broader discussion, and that it “was concluded amidst the polemic that has broken out regarding respect for the autonomy of the Commission for the Defense of Human Rights (CODDEHUM).” It should be recalled that Governor Ángel Aguirre Rivero named Ramón Navarrete Magdaleno as head of CODDEHUM, an action that was considered to have exceeded the authority of the Executive.

Oaxaca: the Tehuantepec Isthmus, principal red alert

The principal red alerts in terms of social conflict continued in the Tehuantepec Isthmus, where organizations and communal assemblies in defense of the territory have continued to denounce attempts at arrest, harassment, expulsions, and attacks against those who have carried out a struggle to defend the rights of indigenous peoples and their territories, in the face of attempts by multinational corporations such as Fenosa Natural Gas and Mareña Renewables to build large wind-energy parks on communal lands without free and prior informed consent by the indigenous who would be affected by these projects.

In January, the spokesperson for the Dutch pension fund PGGM confirmed that the transnational corporation Mareña Renewables plans to cancel the wind-energy megaproject it had intended to build in Santa Teresa, San Dionisio del Mar municipality, given that the firm believed the necessary conditions no longer existed to install such a plant in the region. Nevertheless, according to the same source, the project will be transferred to two other sites in the zone.

In other news, the Oaxacan Collective in Defense of the Territories denounced the notification released by the Secretary of Tourism and Economic Development to the municipal authorities of Magdalena Teitipac, announcing the visit to the community by the General Direction on Mining Regulation. In response, municipal and communal authorities cited the previous communal decision in assembly to expel the mining company Plata Real and to prohibit all exploratory and extractive work with regard to the mineral and natural resources of the municipality.

Agrarian problems in the state continue to generate violence. In the latest cases, in December, eleven indigenous people from Santo Domingo Yosoñama, in the Mixteca región, were murdered in an ambush by unknown persons from the San Juan Mixtepec community. The root of the massacre apparently has to do with conflicts over territory that have haunted the communities for nearly 70 years.

In observance of the International Day of Non-Violence toward Women on 25 November, various collectives and organizations carried out acts of denunciation in the capital of Oaxaca. For one, a caravan-march carrying dozens of cardboard coffins represented the 240 femicides that have taken place during the administration of Gabino Cué. The organization Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Gender Equity denounced the inefficacy of the Oaxacan justice system, which via omission has allowed for an increase in disappearances and murders of women, stressing that 99% of the cases remain unresolved, with the perpetrators unpunished. As of mid-February, 12 women had been murdered in the state so far this year.