SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (From mid-February to mid-May 2014)

21/05/2014

IN FOCUS: Central American Migration to the U.S. – Recognizing refugees on the “infernal route”

05/09/2014While the structural reforms that have been promoted by President Enrique Peña Nieto continue to advance through the approval of secondary laws (particularly in the energy sector) and amidst rumors regarding the economic benefits that legislators will accrue due to such “successes,” processes of mobilization and challenge regarding respect for and promotion of human rights also continue.

In July, for example, the Mexican Congress approved the secondary laws on telecommunications reform. Among the polemical points regarding these laws is the possibility that the authorities would be able to locate a telephone device at any time and place for “security reasons” or to prosecute a presumed crime; and the ability this law gives to the State to order a shutdown of telecommunications services in a given area. Furthermore, it has been indicated that the legislative process to approve such reforms has been marked by irregularities, beginning with the participation of lawmakers who have work, business, or familial ties to television companies. Opponents of the law affirm that it is really a question of a “Peña-Televisa Law” or a “gift” to that corporation as compensation for its favorable coverage of Peña Nieto during his presidential campaign, as PAN Senator Javier Corral Jurado has observed.

It should be noted that several mobilizations have occurred against a reform that has not yet been passed: agrarian reform. On 23 July, between 25,000 (according to the government of Mexico City) and 35,000 campesinos (according to organizers) marched in the capital city to demand comprehensive agrarian reform, to reject the energy reforms, and to demand respect for collective rights.

“Regression in the observance of human rights”

With respect to the extraordinary period of sessions held by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in Mexico in August, civil networks and organizations requested that this mechanism carry out a brief official visit “in view of the regression in the observance of human rights” in the country, which occupies first place in the number of requests for protective measures before the IACHR. In this sense, diagnostics and cases were presented that illustrated the gravity of the situation.

In June, Christof Heyns, the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, presented the report of his visit to Mexico the previous year. The report highlights the high number of homicides in Mexico -100,000 since 2006- 70 percent of which are related to drug trafficking. Other criticisms have addressed the tendency seen by some observers of the federal government to “disappear the disappeared.” These critics question the statistics presented to the UN in March regarding the death toll seen during the previous federal administration headed by Felipe Calderón, as during Peña Nieto’s current six-year term, pointing out the discrepancies between these figures and those that have been collected by local and state authorities as well as civil organizations.

In August, the preliminary hearing on “Gender Violence and Femicide” of the Peoples’ Permanent Tribunal (TPP), Mexico chapter, was held in Mexico City. The different types of violence against women that happen in the country were examined at this hearing, including femicide, discrimination, criminalization, workplace violence, attacks on journalists and human rights defenders, obstetric violence, and human trafficking. Presenters indicated that their data show the depth of violation of the international treaties signed and ratified by the Mexican government, which rules through “simulation and impunity.”

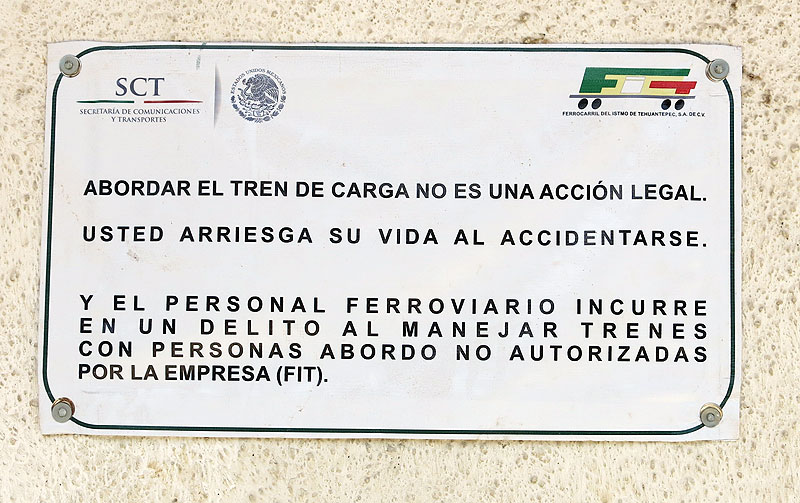

One of the issues that has received greatest media attention of late has been that of migrants (please see In Focus). In July, Carlos Bartolo Solís, director of the Migrant Home “House of Compassion” in Arriaga, Chiapas, announced that he had received death threats from organized crime groups. Civil organizations from southeastern Mexico have been denouncing that the new federal strategy toward greater control of the southern border contains “numerous ambiguities and maintains a vision of national security that prioritizes the management and control of migratory flows over human security.”

CHIAPAS: “Counterinsurgency continues to operate”

© SIPAZ

In July, the preliminary hearing for the Peoples’ Permanent Tribunal (TPP) was held in El Limonar, Ocosingo municipality, which focused on the theme of the Dirty War. The pre-hearing considered the case of Viejo Velasco, where a 2006 massacre resulted in the execution of four persons and the forcible disappearance of four others. The invitation to the hearing noted that “this massacre took place within the context of counterinsurgent war as designed and implemented by the Mexican State by means of the Chiapas Campaign Plan ’94, which had the [following] result[s …]: 85 executions, 37 forcible disappearances, and more than 12,000 people forcibly displaced in the northern Zone, and the Acteal massacre in the highlands, when PRI paramilitaries murdered 45 persons, the majority of whom were women and infants […] as well as provoking the forced displacement of more than 6,000 persons.”

In August, the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC) denounced in a bulletin entitled “Counterinsurgency continues to operate in Chiapas” that “in recent months, the unresolved armed internal conflict in Chiapas has been characterized by a continuous aggression against support bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (BAEZLN), with the action of some social and regional organizations being used for State purposes.” The report notes that the CDHFBC has “carried out constant interventions given the gravity of the attacks against BAEZLN, and the [official] response has been governmental parsimony and unwillingness to act. This attitude of indifference maintains and provokes conflicts that are labeled ‘inter-communal’ as a means of hiding the clearly counterinsurgent aspects. The objective is to exhaust the people who resist, struggle, and transform society through their cultures and rights.”

© SIPAZ

On 24 May, more than 4,000 BAEZLN, militia, members of the EZLN’s General Command, and hundreds of persons in solidarity from national and international civil organizations met in the La Realidad community to pay their respects to José Luis Solís López, “Galeano,” a BAEZLN who was murdered on 2 May in that community. Subcomandante Insurgente (SCI) Moisés indicated that those responsible for killing Galeano were the three levels of government and persons belonging to different political institutions. SCI Marcos announced his “death” and explained that his figure was just a media composite image (pantomime) used to attract attention because it suited the interests of the EZLN, adding that the “Subcomandante farce” was no longer necessary. This change took place within a logic of internal reforms that will lead to a completely indigenous leadership for the movement: “the change of command is not being done due to illness or death, or because of internal displacement or purging. It happens logically given the internal changes that the EZLN has made and is making […]. But some scholars are unaware of other replacements: The one of class: from the enlightened middle class to the indigenous peasant. The one of Race: From mestizo leadership to purely indigenous leadership.”

On 1 August, 32 BAEZLN from the Egipto community belonging to the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipality (MAREZ) San Manuel, in the official municipality of Ocosingo, from the La Garrucha caracol, were forcibly displaced due to the aggressions of members of Pojcol ejido (Chilón municipality). Fifteen days later, the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights denounced the persistence and increase in attacks against BAEZLN in communities around Ocosingo and expressed its “concern for the imminent risk to life, security, and physical integrity which the BAEZLN” of the El Rosario, Kexil, Egipto, and Nuevo Poblado San Jacinto communities face. The CDHFBC held the Chiapas state government responsible “for ignoring the initial denunciations, thus allowing the perpetration of increasingly flagrant violations of human rights.”

It should be stressed that these acts took place around the time of the First Meeting of the Zapatista Peoples with the Indigenous Peoples of Mexico, which took place in La Realidad in August. Some 1,300 Zapatista delegates and more than 300 indigenous representatives of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) participated in the event. They denounced the different situations of plundering that indigenous peoples confront in the country, declaring that “today we say to the powerful, to the companies and bad governments led by the criminal supreme leader of the paramilitaries Enrique Peña Nieto that we won’t surrender, we won’t sell out, and we won’t give up.” They announced that at year’s end they will organize the “First Global Festival of Resistance and Rebellion against Capitalism.”

Chiapas: human rights defenders under watch

© SIPAZ, archive

On 29 May, a commission comprised of leaders and representatives of the Council of Communal Properties of the Lacandon Community Zone, members of the Independent ARIC organization, and a member of the civil organization “Services and Advising for Peace” (SERAPAZ), Mario Marcelino Ruiz Mendoza, who accompanied the commission as a mediator, were arrested. The arrest occurred near the Palace of Government in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, where the commission was convened to begin negotiating with the Secretary of Government. The stated objective of the session was to resolve the agrarian situation in the open conflict in the Montes Azules reserve. Around midnight the same day, the SERAPAZ mediator was released, while the other members of the commission were released the following day, after an accord was signed in Mexico City between federal and state authorities to reopen dialogue. The detainees were accused of riot, attacks on public roads and kidnapping, crimes supposedly committed during the demonstrations, and roadblocks that occurred in the previous weeks in Ocosingo to protest against what their participants consider the interference of environmental organizations in the communities’ decision-making.

In June, the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights denounced acts of surveillance and harassment against one of its members as well as members of other organizations. On 29 April, in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, CDHFBC director Víctor Hugo López was followed and monitored from a vehicle on his way to a work meeting. On 23 May, the same vehicle was seen in the premises of the Municipal Sports Centre of San Cristóbal, where the caravan bound for the community of La Realidad was assembling. Inside the vehicle, a person later identified as Felipe Osorio Lazo “was filming in a suspicious manner.” For this reason, the coordinators of the Caravan asked him to identify himself, hand over the camera, and leave the site. Within the camera’s memory they found photographs and video of members of Frayba and other civil organizations.

In June, a pilgrimage of about 3,500 people from the parish and villagers from Simojovel was held to pray for peace, to end violence, and to call on the authorities to “close the bars, nightclubs, prostitution and vice centres which are damaging families.” The pastor of Simojovel, Marcelo Pérez Pérez, has received death threats due to these protests. In July, the Believing People of Simojovel marched again for the same reasons, as well as to denounce the death threats received by members of the Parish Council. They accused the municipal authorities of fostering this situation.

The International Day for Support for Torture Victims was commemorated in June. On this occasion, the CDHFBC presented the report “Torture, mechanism of terror” that lists 17 recent cases in Chiapas.

In a decision that may signal a partial halt to the deterioration in the state, the Code on Legitimate Use of Force, that had been approved in May and challenged for limiting the right to protest, has been overturned.

Land and territory: old and new conflicts

In June, ejidatarios from San Sebastián Bachajón denounced the “officialist” ejidal commisioner Alejandro Moreno Gómez for trying to “hand over [the land] to the bad government,” by organizing an “illegal” assembly in order to convince the courts that the Assembly agrees with the plundering of the communal lands, located near the Agua Azul waterfall. The same month, ejidatarios from Tila denounced the National Forest Commission (CONAFOR) for carrying out projects on their territory without the assembly’s consent.

In July, the “South-Southeast Forum for analysis and construction of alternatives: Land tenancy, use, and usufruct of land for women in Chiapas” was held, with the participation of approximately 300 persons. Participants expressed their opposition to policies that seek to deprive them of their natural resources by means of oil, mining, ecotourist, wind energy, hydroelectric, highway, and airport construction projects and by denying their traditional knowledges. They denounced that these projects are being carried out without any sort of consultation or authorization from indigenous peoples themselves, and with the blessing of governmental institutions.

Finally, it bears mentioning that assemblies are beginning to be organized throughout the region of the planned highway between San Cristóbal de Las Casas and Palenque. The assemblies’ positions should be made public next month. Also, on the other hand, denunciations have begun to be made against the state government’s insistence on launching this project.

GUERRERO: the “systematic use […] of federal prisons […] as a tool of coercion against social movements”

One of the principal demands of organized groups has been the release of their prisoners. Whether this took place during the twentienth anniversary of the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights in July or in the mobilizations carried out for the eleventh anniversary of the Council of Ejidos and Peoples Opposed to La Parota Dam (CECOP) in August, the demands include the release of Marco Antonio Suástegui Muñoz, Julio Ventura Ascencio, and Emilio Hernández Solís (all of them CECOP members), as well as the commanders of the Regional Coordination of Communal Authorities (CRAC): Nestora Salgado, Arturo Campos, and Gonzalo Molina.

Both Marco Antonio Suástegui Muñoz, who was arrested by police in June, and Nestora Salgado García, incarcerated since 21 August 2013, are being held in the federal prison of Tepic, Nayarit. Tlachinollan has denounced the “systematic use that the State Executive has made of medium- and maximum-security prisons as a tool of coercion against social movements.”

In the case of journalists, the body of Jorge Torres Palacios was found without life and bearing signs of torture in June. He had been kidnapped by an armed group near his home. In August, the Proceso magazine denounced that a presumed representative of the Agency of the Military Public Ministry attempted to deliver a summons to appear to its correspondent in Guerrero, Ezequiel Flores Contreras, without any basis whatsoever. Article 19, an organization that seeks to defend journalists, requested that the Secretary for National Defense (SEDENA) clarify the actions. The group stresses that so far this year, 15 attacks on journalists and media have been reported in Guerrero.

In terms of land and territory, which is at the heart of many struggles in the state, it should be mentioned that the representatives of the Me’phaa indigenous community of San Miguel del Progreso-Júba Wajiín, Malinaltepec municipality, together with Tlachinollan have requested that the Supreme Court for Justice in the Nation (SCJN) “analyze for the first time if the existing Mining Law is compatible with the Constitution and international human rights treaties.” In February, the community obtained an injunction against two mining concessions that had been awarded without previous consultation to the transnational corporations in question.

The question of forcible displacement continues to be a daily concern. In June, 250 people abandoned communities in the San Miguel Totolapan municipality in the Tierra Caliente of the southern Sierra Madre region, fleeing the violence of narco-trafficking groups. Since 2013, the struggle for the control of this zone has resulted in the displacement of more than 2,000 persons. Civil organizations have pointed to the lack of interest on the part of the state government in resolving the problem.

Meanwhile, impunity in past cases continues unchecked: in June, the nineteenth anniversary of the Aguas Blancas massacre was observed (in 1995, 17 campesinos belonging to the Campesina Organization of the Southern Sierra [OCSS] were killed by police), as was the sixteenth anniversary of the El Charco massacre (11 killed by the military). Beyond this, 40 years after the forcible disappearance of Rosendo Radilla Pacheco and five years after the Inter-American Court on Human Rights (IACHR) handed down its sentence in the case, civil organizations and relatives denounced that the Mexican State has failed to observe its obligation of finding the whereabouts of Rosendo Padilla and continues not to investigate those responsible.

OAXACA: among the states with the most attacks on rights defenders and journalists

© SIPAZ

A question of concern continues to be the constant attacks on journalists and human rights defenders. In August, Octavio Rojas Hernández, director for Social Communication in the San José Cosolapa municipality and contributor to the Veracruzan daily newspaper El Buen Tono, was murdered. Article 19 recalled that, “from 1 January 2007 to the first half of 2014, at least 139 attacks on the press in Oaxaca were registered, thus making it one of three Mexican states with the most attacks on journalists in the past seven years […]. Of the total number of attacks, four have been murders, 75 physical attacks, 27 death threats, 13 acts of intimidation, and six arbitrary arrests, to mention just a few. In 58 percent of the cases, the presumed responsible parties are public officials.”

With regard to human rights defenders, the Gobixha Committee for the Comprehensive Defense of Human Rights (Código DH) in July denounced having received telephone calls threatening workers for having accompanied penal processes in the Tehuantepec Isthmus as well as members of the Popular Assembly of the Juchiteco People (APPJ), who have been manifesting their opposition to the construction of wind energy plants. It should be mentioned that both Código DH and the APPJ have been the object of physical attacks, death threats, harassment, and intimidation against their members and in various communities on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. In July, a female activist and human rights defender, member of the Union of Communities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus (UCIZONI), was sexually assaulted by a soldier while she was en route to Oaxaca de Juárez to take a class.

According to data provided by the Registry of the National Network of Female Human Rights Defenders in Mexico, from January to August 2014, 38 attacks were registered against 17 female defenders, 3 female journalists, and 5 organizations in the state of Oaxaca. This makes Oaxaca the state with the most attacks on female human rights defenders and journalists in Mexico.

Another vulnerable sector continues to be communal defenders, who are generally organized in defense of land and territory. For example, members of the Council of Peoples United in Defense of the Verde River (COPUDEVER) accused the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) and local PAN deputy Sonia López of having pressured local authorities and residents of the region to accept the construction of the Paso de la Reina hydroelectric dam. According to the protestors, pressure has increased since Enrique Peña Nieto released details about the National Infrastructure Program (PNI), which proposes to build 189 projects in the southern and southeastern regions of the country, including the Paso de la Reina dam. They detailed that the CFE seeks to pressure communities by promoting infrastructural works such as electricity, potable water, and education. They warned that “the Mexican Army has established a presence in the territory to be affected by the project, with the intention of intimidating the people using the pretext of improving local security.”