2007

02/01/2008

ANALYSIS: Mexico: growing polarization

30/05/2008NAFTA and social discontent

According to the majority of Mexican social and civilian organizations, we’re facing a dark panorama as we enter 2008. These organizations highlight the increase in the costs of basic products, fuel and electricity, as well as the possible consequences of opening the fishing and farming markets as part of the North American Free Trade Agreement, signed in 1994 by Mexico, the United States and Canada.

On 1 January 2008, the NAFTA clauses regarding the cancellation of taxes on basic grains such as beans and corn, as well as milk and oil products, came into effect. Despite protests by farmers towards the end of 2007, the Mexican government has refused to renegotiate these articles. Campesino groups, the federal opposition and several academics have warned that Mexican farmers aren’t ready to enter into competition – either in regard to prices or to quantity of products – with powerful US producers. This difficulty is particularly acute when one compares the difference in the subsidies offered on either side of the border. According to the representative of the National Campesino Confederation (Confederación Nacional Campesina, CNC), Cruz López Aguilar, more than 1,400,000 corn, beans and rice producers are at risk from the total access to imports to the Mexican market.

According to the Secretary of Agriculture, Cattle-farming, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación, Sagarpa), Alberto Cárdenas, contrary to the opinion expressed by several campesino organizations, NAFTA has had a positive impact. “While NAFTA has brought Mexican producers into greater competition, it also opened multiple opportunities to access a regional market of more than 430 million people.” Cárdenas declared that Mexico is in good conditions for the commercial liberalization as “the [tariff] deduction process had been slow and sure,” and as of 2007 some 90% of tariffs had already been eliminated. As a result, in 2008 “there shouldn’t be any significant changes in their [the farmers’] market situation, particularly given the high prices predicted for the coming months.” He added that with NAFTA opening up the markets, “subsistence farmers won’t suffer any ill effects, as they in fact don’t participate in that market; on the contrary, they will benefit from the access to goods and services at more accessible prices.”

Bearing the motto of a campaign launched in 2007, “Without corn and beans there is no country” (“Sin maís no hay país, sin frijol tampoco”), campesinos and producers have been organizing themselves. In January, some 20 organizations announced their alliance as a National Front to Defend the Mexican Countryside (Frente Nacional en Defensa del Campo Mexicano). The Front has demanded government measures to confront the crisis situation caused by the market opening, and they called a mega-protest for 31 January 2008, at which they expect the attendance of social and trade union organizations.

Federal government: “iron fist” and increasing militarization

In line with increasing social pressures, complaints against the “iron fist” policy of Felipe Calderón’s government – as well as the process of increasing militarization across the country – continue to be heard. This tendency has become even more marked with the recent announcement of new forms of collaboration between the United States and Mexico, launched under the pretext of the fight against “drug trafficking and terrorism.”

One plan which continued to be strengthened in 2007 was the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (SPP), an agreement between Mexico, Canada and the United States initiated in 2005. The SPP is presented as an enhanced free trade agreement, adding security elements to those of development and commerce.

Simultaneously, the governments of the United States and Mexico are about to finalize an agreement aimed at supporting the fight against drug trafficking and organized crime in Mexico. The idea took shape in March 2007, when US President George W. Bush visited the Mexican city of Mérida. Because of its similarity to Plan Colombia (a policy implemented almost a decade ago in Colombia which involves the contribution of US $4.3 billion to the Colombian government, 76% of which is military aid), this new initiative is known as “Plan Mexico;” to a lesser degree, its official name “The Merida Initiative” is used.

The Bush Administration has proposed to ask Congress to approve a joint package of US $1.4 billion to be distributed over three years (thus committing the incoming Administration, following the 2008 elections, to fulfill the obligation). The package has been presented to Congress as “emergency funding for other critical national security needs.” The proposal highlights the Initiative as “vital assistance for our partners in Mexico and Central America, who are working to break up drug cartels, and fight organized crime, and stop human trafficking. All of these are urgent priorities of the United States, and the Congress should fund them without delay.” In this context, it is worth noting that in 2007 there were more than 2,000 deaths linked to organized crime, and that the US shares a border of more than 3,000 km with Mexico.

The first consignments of funds will be directed to the supply of military equipment and communication and surveillance technology, as well as various forms of capacity building for Mexican soldiers and officials. For the time being, there are no plans to deploy US troops in Mexican territory.

Worrisome factors which have been named by human rights groups on both sides of the border include the fact that more than 40% of US $500 million authorized for distribution in the first year will be directed to the military sector, despite the serious accusations of human rights violations committed by the Mexican army in national security operatives. In October, Human Rights Watch (HRW) declared that the US Congress should oppose the anti-drug assistance to Mexico, unless the agreement includes strict conditions designed to halt abuses committed by Mexican security forces. José Miguel Vivanco, Americas Director at HRW, stated, “helping Mexico confront its brutal drug cartels is a good idea. Giving a blank check to that country’s abusive security forces is not.”

© La Revista Peninsular

Other analysts highlight that there is no guarantee of gaining improved outcomes in the fight against drug trafficking when the powerful offensives launched by Felipe Calderón at the beginning of his six-year term have as yet not had the expected results. Mexican critics note that the fact that Washington locates the battle against drugs and delinquency in Mexican territory as one of the “critical needs” of its national security demonstrates interference. In addition, the reference to the topic of “people trafficking” brings into question whether this could allow for the persecution of Central and South American migrants to Mexico, or even including Mexicans who attempt to cross their nation’s northern and southern borders.

In October, at the 1st Integration Meeting of the Governors of the South–South-Eastern Region in Villahermosa, Tabasco, the “security” factor seemed to be given greater emphasis than the issue of “development.” During a meeting with Mexico’s nine southern governors, Felipe Calderón said that he would give “renewed thrust” to Plan Puebla-Panama (PPP), asking that it be converted into a “project of integral development for Mesoamerica.” However, Calderón stressed the reinforcement of the southern border given the “collapse” of the local authority’s capacity to control it.

Red light on human rights

Despite the preoccupations expressed by the Interamerican Human Rights Commission of the Organization of American States (OAS), as well as various national and international human rights organizations, the definitive approval of the Executive’s proposed penal reform appears to be imminent.

Concerns have been raised that the penal reform will be contrary to the presumption of innocence and due process of the law. It will allow the Federal Public Prosecutor’s office and any police corps to tap phones, and enter and search private homes – this without a warrant, only relying on the suspicion that the individual has a presumed connection with organized crime or that he/she may be in the act of committing a crime.

The President of the National Human Rights Commission (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos, CNDH), José Luis Soberanes, affirmed in December that the legal reforms “represent a backward step in terms of human rights, as illegality cannot be fought by stepping on the most basic guarantees.”

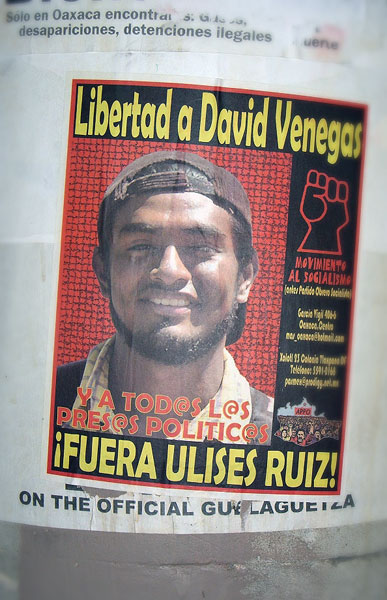

Even though the reform has not yet come into effect, several human rights organizations have pointed out the risk of legalizing the criminalization of public protest. In the last months, the issues of prisoners and repression in general has been a topic which has generated denunciations and created alliances. On 1 November, for example, the National Front Against Repression (Frente Nacional Contra la Represión, FNCR), which united diverse organizations and movements, held a meeting in front of the Government’s Secretariat to demand the freedom of all of Mexico’s “political prisoners,” the safe return of all forcibly disappeared people, the abolition of torture, the end of sexual aggressions and violations against women, and the cancellation of arrest warrants and persecution against social justice activists.

In November, the Solidarity Network Decade Against Impunity launched a report entitled “The Situation of Political Prisoners in Mexico,” in which they quote the figure of 500 political prisoners. The Network recognizes the difficulties of calculating an accurate figure, given the limited documentation available and the conditions in which the court cases are conducted.

The release of indigenous prisoner Diego Méndez Arcos (detained in 2006 for his alleged participation in the deaths which occurred in Viejo Velasco, Chiapas) at the beginning of December is, like his detention, an example of the arbitrary nature of the judicial process.

In other news, an issue which places Mexico at the “head in the matter of limiting the freedom of expression” (according to Amerigo Incalcaterra, representative of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights) is that of threats and assassinations against journalists.

In a ranking released in October in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index 2007, Mexico continues to be the most dangerous country in the Americas for journalists. It appeared in position 136 of the 169 nations included in the study. Benoît Hervieu, head of the Americas desk at Reporters without Borders, emphasized, “for more than a year, the federal government of Mexico has been going backwards in terms of press freedom, and it demonstrated this during the crisis in Oaxaca.” Hervieu pointed out that this regression in the press situation reflects the lack of political will shown by the federal government to advance on this issue.

In January, the National Human Rights Commission announced that it had opened 84 complaint cases in 2007 because of violations of individual safety against journalists acting in a professional capacity. The Commission revealed that the cases had multiplied and are in fact more violent than in previous years. The recent dismissal of journalist Carmen Aristegui, anchor of the W Radio news program “Hoy Por Hoy”, also generated grave concerns about the issue of freedom of expression in Mexico.

Another case which has caused a flurry of articles is that of journalist Lidia Cacho. At the end of November, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) eliminated from its final judgment in her case any information concerning sexual abuse, pedophile networks and child pornography. This information was considered unrelated to the investigation against her, which was being coordinated by a group of Mexican authorities, led by Mario Marín, Governor of Puebla. The National Front Against Repression expressed their concern that the SCJN had shown “indolence” in the matter, even before they came to the session when they would consider the cases of the conflicts in Oaxaca and San Salvador Atenco. The High Commissioner of the United Nations (UN), through her representative in Mexico, declared that “it would have been an important opportunity to confirm the principles which the country has already ratified.”

CHIAPAS: Zapatistas readjust their strategic position because of threats

Between 13 and 17 December, an international colloquium was held in memory of Andrés Aubry, a French historian who worked in Chiapas for more than 40 years until his death in September 2007. Hosted by the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), CIDECI-Unitierra and the Immanuel Wallerstein Center, participants in the colloquium included such national and international personalities as John Berger, Naomi Klein, François Houtart, Pablo González Casanova, Sylvia Marcos, Enrique Dussel, Jorge Alonso, Carlos Rojas Aguirre and Jean Robert, who spoke to the crowd of several hundred people.

In his last speech, “Feeling Red: The Calendar and Geography of War”, Subcomandante Marcos clarified his role as military leader of the EZLN, an army he defined as “a different one, it’s true, but still an army.” He announced, “this is the last time, at least for a while, that we come out for activities of this type I’m referring to the colloquium, meetings, round tables, conferences, in addition to, of course, interviews.”

Marcos explained that this decision was made as a response to a new wave of aggressions: “but it is the first time since that early morning in January of 1994 that the social, national, and international response has been insignificant or null. It is the first time that these aggressions cynically come from supposedly leftist governments, or that they are being perpetuated with the support, without hiding it, from the institutional left.” In addition, the Subcomandante warned, “we will try to continue the consolidation of the civil and peaceful effort of what we still call ‘The Other Campaign,’ and, at the same time, we’re prepared to resist, alone, the reactivation of the aggressions against us, be it through the army, police or paramilitary groups. Those of us who have made war know how to recognize the paths through which it is prepared and how it comes closer. The signs of war on the horizon are clear. The war, like fear, also has a smell. And now we can begin to breathe its stench in our lands.” A document signed by the participants in the colloquium echoes this position: “We cannot allow another Acteal in Mexican territory. The people cannot be sidelined to the point where they defend themselves from violence with violence.”

For the same reason, in September 2007 the EZLN announced the suspension of the tour planned with The Other Campaign (a peaceful initiative promoted by the Zapatistas at a national level) in order to concentrate their energies in defensive actions to protect their communities. In the last few months, several aggressions against the support bases have been denounced. These have principally come from the PRI-affiliated organization OPDDIC (Organization for the Defense of the Rights of Indigenous People and Campesinos, Organización Para la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas y Campesinos). In a dispute over territory which is becoming progressively more open, the cases in question range from the north of Chiapas (the case of Bolon Ajaw in November, in the autonomous municipality Región de la Montaña, officially known as Tumbalá, a tourist destination because of its proximity to the waterfalls of Agua Azul), passing through the Tseltal region of Chilón, part of Las Cañadas, and arriving in the Highlands of Chiapas (with the October death threats against the Autonomous Council of the Municipality of San Andrés Sakamch’en de los Pobres.

A caravan comprised of members of The Other Campaign, which traveled through parts of Chiapas in November, denounced the following: “The federal and state governments, through the institutions of agriculture and in coordination with the Mexican Federal Army and public security forces at the three levels of government, have put into operation a counterinsurgency strategy against the Zapatista support bases and their autonomous authorities. Agrarian land titles have been granted to different indigenous organizations, particularly those adverse to the Zapatistas, and in several cases armed organizations. Among these is the Organization for the Defense of the Rights of Indigenous People and Campesinos (OPDDIC) and the Regional Campesino Indigenous Union (Unión Regional Campesino Indígena, URCI). […] These organizations are occupying lands reclaimed by the EZLN in 1994 and, via the agrarian authorities, they consolidate the legal plundering of Zapatista lands by constituting new ejidos [community farming lands].”

Armed groups: communiqués

In October, the Revolutionary Popular Army (Ejército Popular Revolucionario, EPR) threatened to escalate their “national harassment campaign” if the government did not safely return their combatants who were forcibly “disappeared” in May 2007. The EPR made clear that it would “never” seek dialog with the federal government, but rather that this was a proposal made by several senators in September. In December, the EPR announced the reopening of hostilities against the government of Felipe Calderón. In January, the group indicated that it would give advance notice of any military attacks it would conduct. They also warned legislators that “those from the Chamber of Representatives and Senators, from any political party, who approve the judicial reform proposed by Calderón which criminalizes protest, the fight for social justice and acts of self-defense, should be ready to take responsibility for the consequences of their actions.”

For their part, in November the Revolutionary Movement Lucio Cabañas (Movimiento Revolucionario Lucio Cabañas), one of the guerrilla groups which placed explosives in the seats of the Electoral Tribunal and some banks in Mexico City in 2006, warned that the Merida Initiative signed by the Mexican government with the United States would be repelled by actions from mass movements and revolutionary groups.

… … … … … …

Flooding In Tabasco And The North Of Chiapas

Towards the end of October, the national and international media became aware of a serious natural disaster. Strong rains assaulted the state of Tabasco and the north of the neighboring state of Chiapas, causing floods which affected around one million people – with their homes, crops and cattle in 16 of the 17 municipalities of Tabasco. According to Tabasco authorities, some 400,000 people were left in dire conditions. At least 90% of the state capital of Villahermosa was underwater at some point.

Receiving less media attention, the rains in the north of Chiapas caused the Peñitas Dam to burst, resulting in the overflowing of the banks of the Grijalva River and the flooding of Tabasco’s plains. Twenty-two municipalities in the north of Chiapas were declared to be disaster zones, and it is calculated that more than 75,000 people lost everything to the floodwaters.

Even less mainstream media coverage was given to the accusations of the State’s responsibility in a disaster, which could largely have been avoided. One of these dissident voices is Jorge Escandón, spokesperson on Energy and Climate Change for Greenpeace Mexico, who highlighted that, “in the specific case of Tabasco, where there was significant flooding in 1999, and no measures were subsequently taken – not to control the flooding itself, but to permit a more efficient government response – the situation can be attributed to political negligence.”