IN FOCUS : Mining in Chiapas – A New threat for the survival of indigenous peoples

29/12/20082008

01/01/2009The backdrop of the global economic crisis has led to predictions that Mexico is entering a stage of general economic deceleration at every level but mainly with regards to growth, consumption and employment.

Hopes for a quick recovery are unfortunately tied to the country’s dependence on the United States economy. The head of the Secretary of Social Development, Ernesto Cordero Arroyo, admitted that the deceleration of the US economy has provoked higher levels of unemployment and a drop in remittances that Mexican immigrants send back to their families (USD 53.5 million less than 2007), which will in turn “affect the Mexican families that live in poverty.” Given this context the Mexican Secretary of Finance called on families to “be prudent” and to “save for any possible event that the future may present.”

In early October President Felipe Calderón presented a new financial program in an attempt to minimize the negative impacts that the financial crisis in the US could have on Mexico. He was also forced to adjust the 2009 national spending plan due to the crisis.

As of September 1, after submitting his second Government Report, Felipe Calderón confirmed that an “adverse external economic setting” affected the possibility of meeting national goals regarding inflation, growth and employment generation. The opposition members of the Lower House confirmed that in the first two years of the Calderón administration some 1 million 300 thousand Mexicans have left the country due to a lack of employment. That same day, campesino, social and labor organizations took to the streets in several regions of the country “to demonstrate the growing discontent and frustration of the labor force” with the government’s economic, labor and energy policies.

The “War on Drugs” Maintains Priority in Government Policy

According to the Second Government Report: “Since the inauguration of the current administration, some 46 high impact operations have been carried out (…) with an average participating force per month of 45 thousand soldiers.” The Calderón approach is much more aggressive than that of the previous administration making it a truly “new strategy of the National Defense Secretary in the war on drugs.”

Despite these efforts, the numbers of executions carried out by organized crime syndicates had continued to increase in the first semester of 2008 reaching 2,673 deaths, equal to the total number of deaths during the whole of 2007. In early December the Federal Attorney General had already cited 5,400 deaths to the date and he assumed that the number would rise before the end of the year.

In late August, the federal government admitted to the existence of an “institutional and structural deterioration” in the fight against organized crime, as well as the corrosion of channels used to reverse the “high level of impunity” and “territorial control” that criminal organizations currently possess. In this light Calderón presented the National Accords for Security, Legality and Justice which by means of 75 points attempts to purge and reinforce the police and prosecutorial institutions.

One of the first major questions brought before the National Accords was the lack of obligatory implementation or sanctions for those who fail to comply with the accords. Specialists also confirmed that the Calderón government initiated the call for a “war on drugs” without sufficient civil or military intelligence work in addition to the fact that he did not predict the “violent dimension that the narcotraffickers’ response has taken on” or the corruption and infiltration that would surface within the police forces (La Jornada, Sept 29, 2008).

In October the initiation of Operation Clean Up made clear the level of narco infiltration at the highest levels of government. The Federal Attorney General confirmed that since 2004 organized crime elements had been co-opting high ranking officials within the organized crime unit of the Federal Attorney General’s Office (SIEDO, Subprocuraduría de Investigación Especializada en Delincuencia Organizada). Several of these individuals have been selling classified information to the Beltrán Leyva cartel.

In late November, 100 days after the signing of the Accords, the federal government assured the public that it had complied with the obligations implied in the Accords along with the reassigning of resources within the proposal, the reinforcement of civil society, the adapting of the model to the institutional coordination in addition to the presentation of the reform package to Congress. The administration congratulated the Congress on its approval of an increase of some 35% to the spending plan for security, almost doubling the funds destined for social development next year.

Deputies and senators from the PRI (Partido de la Revolución Institucional) and PRD (Partido Revolucionario Democrático), as well as representatives from a number of diverse churches argued that the results expected as put forward by the National Accords at the end of the 100 day period would be “meager and insufficient.”

Whether or not they were connected with organized crime, two events reinforced the general perception of insecurity in Mexico. The first took place September 15 during the Independence Day celebrations when two explosions went off in the main plaza of Morelia, the capital of Michoacan, leaving 7 dead and 132 injured.

The other event took place on November 4 when the Secretary of the Interior, Juan Camilo Mouriño, and the former head of SIEDO, José Luis Santiago Vasconcelos, were killed in a plane crash in Mexico City. The crash left 15 dead and 40 injured. Both Mouriño and Vasconcelos were two major anti-narco strategists within the Calderón administration. While Mouriño was very close to Calderón, Vasconcelos was according to several media outlets the individual most trusted by both the Mexican army and the United States. Although the official version affirms that there was no evidence of foul play in the crash, it has continued to be a controversial issue as public opinion continues to be open to the idea that the incident was connected to narcotrafficking.

International Support in the Fight Against Organized Crime

© El Siglo de Torreón

In 2008, Mexico moved from 4th to 2nd place in Latin America in terms of military and policing assistance from the United States, following Colombia. The Merida Initiative, which consists of some USD 400 million in assistance to Mexico for 2008, is intended to create deeper integration in terms of security between the United States and Mexico. The Mexican government was expecting the assistance as early as September, however it was not until December 3 in a low profile ceremony that a Letter of Agreement was signed and the first USD 197 million of the USD 400 million already approved by the US Congress.

Mexico also solidified several other international agreements. In October, together with the government of Brazil, Calderón signed an agreement to strengthen a partnership in the exchange of information, programs and experience to reduce crime. He also met with representatives from the European Union to discuss the Strategic Alliance between the two entities that will permit further collaboration on the themes of climate change, organized crime, the fight against poverty, human rights and immigration. In addition Calderón met with Argentine president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner to discuss a partnership against transnational organized crime, drugs and money laundering.

The Energy Reform Approval

After 8 months of analysis and negotiations, which included several forums with the participation of more than 100 experts, the energy reform was finally approved by the Mexican Congress on October 23. The reform will give Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX, nationalized since 1938 and a symbol of national sovereignty) more budgetary and procedural autonomy, modernize its institutional design and loosen its acquisition and public works contracting process.

The opposition to the possible privatization of PEMEX was organized through the National Movement in Defense of Petroleum and the Popular Economy headed by the ex-presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). Meanwhile, left leaning legislators had pointed out that although they were in favor of the reform in general terms, they felt that some aspects needed clarification. The day of the approval, the congressmen took the stage after AMLO met with legislators from every party and asked for the inclusion of a clause that would expressly prohibit concessions for exploration or production of crude oil to foreign companies. This caveat however was never approved.

Although the initiative was ultimately quite different from that proposed by Calderón (which, for example, would have allowed private companies to build and operate refineries), he did state that the approval of the reform was a “historic” achievement and asserted that “with the reform, both the national economy and the Mexican people win.” The only people who did not express approval were Mexican entrepreneurs and foreign investors as they felt that the reform was extremely limited.

The reform integrates several of the proposals brought up by the Broad Progressive Front (FAP, Frente Amplio Progresista is a coalition of the major parties from the left in Mexico: the Democratic Revolution Party [PRD, Partido de la Revolución Democrática]; the Worker’s Party [PT, Partido del Trabajo]; and Convergence [Convergencia]). However, the approval left several factions of the PRD and FAP further divided. In mid November, after eight months of a tumultuous internal process in defining the election of its national director, the Federal Electoral Tribunal (TEPJF, Tribunal Electoral del Poder Judicial de la Federación) revoked the nullity of the internal PRD elections which took place in March and recognized Jesús Ortega Martínez as the new national president of the party. It has been noted that Ortega Martínez represents a tendency within the party that is more distant from AMLO.

After the approval of the energy reform, AMLO announced a new stage of the National Movement in Defense of Petroleum and the Popular Economy. He warned that the legions of citizens who make up the movement will not disband but rather will continue the struggle against the high cost of living and in defense of better wages.

Human rights: “good intentions” in the face of the same concerns

At the end of August, the new National Program for Human Rights 2008-2012 was published in the Mexican Official Newspaper of the Federation. This document raises the possibility of a gradual withdrawal of the armed forces from public security tasks and proposes “to initiate reforms in matters of management and implementation of military justice in accordance with international human rights agreements ratified by the State of Mexico.” It also discusses the creation of guidelines for the use of force with respect to human rights. Civil organizations have questioned this program as being a “list of good intentions.”

One of the most worrisome tendencies continues to be the criminalization of social protest in the face of growing militarization in the country. In October, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) denounced that up to this point in the Calderón administration they have received 983 complaints of human rights violations against the armed forces: “the militarization of public security has provoked torture, extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detentions, and sexual abuse on the part of the military; nevertheless, the payment of more than 45 thousand in cash for public security projects has not succeeded in stopping the amount of violence.”

A new platform for human rights will open in February 2009, when Mexico will undergo an examination by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations (UN), as part of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) which all member nations must undergo.

In September, more than a hundred organizations presented in Geneva, Switzerland, a special report in which they denounced that “Mexico has not fulfilled its international compromises” and that torture, forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, limits to freedom of expression, and impunity still exist. The report included 60 cases of criminalization of social protest in 17 states in Mexico.

At the end of November, Mexico presented its report to the UPR. It stated that the use of the army for fighting against organized crime is a provisional measure to re-establish minimal conditions of public security “with full respect for human rights.” As an example they proposed the creation of an Office of Human Rights within the Department of National Defense (which currently does not have proposed funding for 2009). The Mexican human rights organizations demanded that the Mexican government attach a date to the withdrawal of the armed forces, which is also stipulated in the document.

In November, the Department of External Affairs (SRE) stated that Mexico was chosen to be a Member of the Board of the Assembly of States, Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court for 2009-2011. The naming of Mexico illustrates the intense international activism on the part of Mexico in the area of human rights, which according to NGOs working in the area of human rights, is in contrast to the actual situation in Mexico.

Chiapas: impunity and new conflicts

In November, two years after the killing of indigenous people in the community of Viejo Velasco (north of Montes Azules), the deaths of the six individuals continue to go unpunished.

On October 3 of this year, a violent operation carried out by federal and state police left a toll of six dead (4 were executed according to the testimonies of community members), 17 wounded, and 36 detained, almost all residents of the ejido Miguel Hidalgo, located in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas. On September 7, the members of the ejido took control of the ruins of Chincultik which are located directly across from the community, with the intention of administering the archeological site themselves.

The state and federal authorities have opted to pay 35 thousand pesos for funeral expenses and 75 thousand pesos for economic support for those who lost family members. The Chiapas state government has also accused 5 police of being responsible for the massacre and has promised to punish those who are convicted of excess in carrying out their duty. After these events and after the Chiapas Secretary of Government recognized that there had not been an eviction order, the State Congress unanimously approved an eviction protocol for the state and municipal security forces, which attempts to regulate the use of public force.

The International Civil Commission for the Observation of Human Rights (CCIODH) stated that this is a clear example of the government policy of criminalization of social protest in which the state seeks to put aside the possibility of dialogue and political solutions to the conflict and instead attempts to limit institutional responsibility by appeasing the community through reparations. The Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de las Casas has also stated that “There exists a great risk that the massacre of Chinkultic, like others, will remain unresolved and that the punishments of those responsible will only be carried out against low level public servants.”

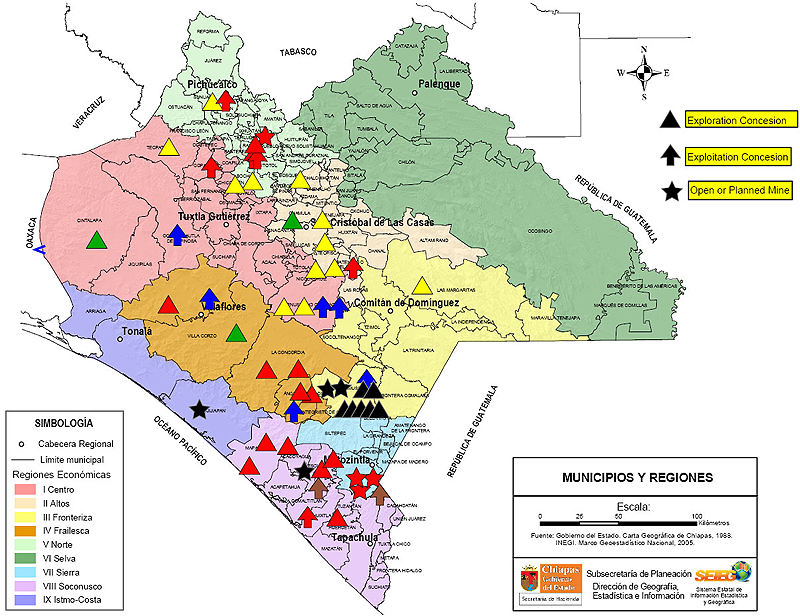

More generally, the main source of conflict is tied to social projects and for the most part, economics: highways (like the announcement of the superhighway from San Cristobal de las Casas to Palenque), tourist projects (theme parks in Palenque and the waterfalls of Agua Azul), and development projects (protected natural areas like Huitepec or the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, and mining among others; see the Focus article in this report).

EZLN: Festival of Dignified Rage (Digna Rabia)

In the first week of August, a national and international solidarity caravan documented a number of violations of human rights in Zapatista territories. This caravan also attended the commemoration of the 15th anniversary of the founding of the Zapatista Good Government Councils (JBG, Juntas de Buen Gobierno).

In September, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) gathered to support the movement for the liberation of the 13 people still held prisoner after the repression in San Salvador Atenco in May of 2006, all of their sentences are for more than 30 years and several leaders of the Peoples Front in Defense of the Land (FPDT, Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra) received up to 112 years. The EZLN also announced the first Global Festival of Dignified Rage, which will be celebrated the last week of December and the first days of January, 2009 in Mexico City and in Chiapas. The communiqué explains that: “Disgust in the face of the cynicism and incompetence of the traditional political parties has become rage. At times this rage gives us hope for a change in the old ways and it halts the immobilizing disillusion and the arbitrary forces which tyrannize us.”