SIPAZ Activities (November 2006 – February 2007)

30/03/2007

ANALYSIS: Chiapas – a reactivation of a state of social conflict

31/10/2007It has been a year, in an over heated social context, since it was predicted that the incoming government of Felipe Calderón would face a series of outbreaks of violence and other destabilizing risks that would affect its ability to govern the country. The demonstrations at the end of 2006 and the massive post-electoral protests reflected a polarized society and a clash between social and government forces.

One year later, it appears that the context has changed; at least that is how the mainstream media has presented it. Although the fundamental causes underlying the social unrest expressed in 2006 have been unresolved, the new government has managed to act as if a state of “democratic normality” has returned.

The government laid out a mano firme (firm hand) strategy, which would use the armed forces in its implementation (see the feature piece in this newsletter). Nonetheless, efforts against organized crime and narco-traffic have up to now not reduced the problem. Not a day goes by without reports of an execution, an ambush, or a shoot-out. Since the beginning of the year, the number of executions has surpassed 1,200.

In the area of economy, the government has advanced in the elaboration of the National Development Plan for 2007-2021, in which social welfare and security are two of its key elements. A re-launching of Plan Puebla Panamá(1) has also been confirmed with a summit held in Campeche, Mexico, between Central American and Latin American Heads of States and Mexican governors. Newly passed laws and those currently being debated, particularly around the issues of labor and taxes, have ignited strong discussion and nonconformity.

Movement in Support of Lopez Obrador: A force to take into account

As has been noted earlier, Mexico faced a political crisis brought on by last year’s electoral process. Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), former presidential candidate for the Revolutionary Democratic Party (together with the Convergencia and the Workers´ Party), after denouncing the fraudulent elections, has tried to politically focus the 15 million persons who voted for him and strengthen the National Democratic Convention (CND) formed in September 2006. The CND designated Lopez Obrador “legitimate president” in light of the allegations of electoral fraud. The group has also proposed that Obrador tour the country’s 2, 500 municipalities. Parallel to this tour has been the creation of a national network of representatives for the “Legitimate Government”. To date, one million representatives have registered with the goal of reaching 5 million by the end of next year.

This process has received little coverage on the part of the mainstream media. In June, the AMLO team denounced a new blow against them when HSBC (Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank Corporation) decided to cancel “for their own reasons” accounts that held the deposits of the “Legitimate Government” supporters.

Although many have spoken of a declining support for López Obrador´s movement because of an apparent inability to draw the large crowds congregated last year, on July 1st, he once again filled the main plaza of Mexico City. The Ample Progressive Front (FAP-integrated by the three parties that supported AMLO in the 2006 elections) took the opportunity to reaffirm AMLO as the “legitimate president” of Mexico. López Obrador began his speech reinforcing the movement’s persistence: “A year after the electoral fraud, we can proudly and decisively say that the right wing and its allies have been mistaken. We are still here, and moving forward, convinced more than ever of the need to push ahead an alternative project for the nation.”

In the aftermath, the principal issues monopolizing national attention in the last months have been the Social Security and Services Institute Law for State Workers (ISSSTE) (a labor reform targeted at state worker), the subject of mass mobilizations in May, immigration, and issues affecting Mexico’s rural areas. In regards to the tax reforms announced by the new government, AMLO responded: “I appeal to representatives and senators of the Ample Progressive Front to by no means approve the tax reforms proposed. Zero negotiations with those who support policies that go against the people and hand over national sovereignty to foreigners.”

Since last year, the Mexican left has experienced a tension between the particular logic characteristic of social movements and another that continues to respect the institutional political party system. For example, against the determination to reject proposed tax reforms assumed in the CND, the National Council and the PRD governors rejected taking far out positions and decided not to exclude themselves from discussions on the issue within Congress. It is also worth emphasizing that unity among the integrated parties of the FAP has not been maintained in many local elections. These parties have faced internal struggles and readjustments unfavorable for building an articulated opposition.

The “Other Campaign” Marches On

At the end of March, in an event held in San Cristóbal (Chiapas), Vía Campesina and the “Movement of Those Without Land” (Movimiento Sin Tierra)of Brazil joined the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in their call for a “Global Campaign in the Defense of Land and Territory of Indigenous Peoples and Peasant Farmers.” By mid-April, more than 200 organizations and persons from 40 countries expressed their solidarity with the campaign.

The second phase of the Other Campaign, in an initiative promoted by the EZLN since 2005 for the purpose of forming an anti-capitalist front, was put in march through sending three delegations of commanders, including the sub-commander Marcos, to tour the northern part of the country at the beginning of June.

In May, just one year after the violent incident in Atenco, the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa de la Tierra de San Salvador Atenco, part of the Other Campaign, denounced the lack of political will to punish those responsible for the murders, 26 sexual violations and acts of torture. For some analysts, Atenco represented the beginning of the criminalization of social movements, a fact that seemed to be corroborated when a few days later a judge condemned three movement leaders to 67 years in prison on “kidnapping charges”, for having detained several officials for several hours.

From the 21st to the 30th of July, the Second Encounter of Zapatista Peoples with the Peoples of the World was held in 5 of the Zapatista Caracoles with more than 3 thousand participants.

Resurgence of the “option to take-up arms”

Recently, the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR), whose presence has been recognized in Guerrero, Oaxaca and Chiapas, claimed responsibility for 8 explosive charges detonated in the ducts of Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) located in Guanajuato and Querétaro. They stated that the bombings were meant as pressure on Felipe Calderón´s government as a means to demand the release of their two members that disappeared in Oaxaca and have not been seen since May. Consequently, they warned of new attacks until their fellow members are liberated.

A few days later, the Lucio Cabañas Barrientos Revolutionary Movement (an armed group that vindicated the bombings against the head offices of the Electoral Tribunal and the Institutional Revolutionary Party in the Federal District of Mexico City in 2006) demanded that authorities present the disappeared EPR members alive and called for its own militants to be ready for future “military actions”. At the end of July, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of the People (FARP, a split of the EPR) warned that they are currently “discussing in order to decide that which no one wants but the tumultuous situation drags us there.” It has been repeatedly pointed out that the closing of channels of communication and negotiation could corner social movements to radicalize their methods of resistance.

Strong doubts in the matter of human rights

In March, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights and the fundamental freedoms of Indigenous peoples, Rodolfo Stavenhagen, pointed out Mexico as an example of a country with the tendency of criminalizing social protest of Indigenous peoples and using public security forces to repress them.(2)

In April, the President of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH), Florentín Meléndez, visited Mexico. In the reports grass-roots organizations turned in concerning the country’s human rights situation, these groups stressed that the president’s government has shown little signs of elaborating a political position in this matter: “[the president] has not made any public declarations over what will be his political position around this issue.” The CIDH criticized the high incidences of attacks against human rights defenders in Mexico. In Chiapas, the Center for Human Rights Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas registered 20 aggressions just in 2006. In the most recent case, in February of this year, members of the Center for Economic and Political Research for Community Action (CIEPAC) received an anonymous note threatening their lives.

In May, in her presentation of their 2007 Report, the president of Amnesty International in charge of Mexico affirmed that the actions of the new government in the defense and promotion of human rights up to now “has been disappointing.” “So far it has not demonstrated the will to elaborate programs that address grave violations in this matter.” She also pointed out that impunity is the phenomenon most rooted “in all the cases of human rights abuses in Mexico, and it is the most important challenge for this government.”(3).

Chiapas: between impunity and new conflicts

In April, in an interview from Spain, Luís H. Álvarez, Chairman of the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and former Commissioner for Peace in Chiapas, indicated that to solve the situation of marginalization of Indigenous communities in Mexico does not require a solution to the conflict in Chiapas, a conflict he himself did not recognize. He pointed out that the “EZLN is not a negotiator with Felipe Calderon’s government” now that it neither represents nor is integrated into Indigenous communities(4).

Even with this perspective, various aspects related to the armed conflict continue to exist and demand present responses. Proof of this was in March, as groups displaced by the military and violence demanded of Governor Juan Sabines solutions to their already old demands: “We lived through forced displacement from our homes, some since 1994. We have suffered from a lack of respect for our human rights as Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, threats, violence, mistreatment of women and children, hunger and death.”(5).

On the other hand, the Governor, Sabines Guerrero, “announced the creation of a special investigative body for the case of Acteal (…) to find the truth behind the homicides committed on December 22, 1997, an injury felt in all of Chiapas and Mexico, in order to not leave any impunity.” However, to date, this body has not presented any reports on the actions undertaken to fulfill the official announcement.

In regards to the issue of militarization (see also the feature article), various communities continue to solicit the exit of military forces from their lands – for example, Nuevo Poblado 24 de Diciembre (formerly Nuevo Momón)(6).. In July, the Center of Political Analysis and Social and Economic Research (CAPISE) projected that the issue of military presence in Chiapas would be less prevalent in public opinion now that militarization has become a general phenomenon around the national territory. However, they point out that even though the federal military has withdrawn units and bases, they have also brought in new “elite” forces with significant offensive capabilities, coordinated directly with the 1st Military Unit of Mexico City and not the usual command in the military zones of Chiapas as had been the custom up until 2006 (7).

Parallel to this, various organizations have denounced the reactivation of paramilitary groups in different municipalities in the northern zone and jungle region of Chiapas. One of the organizations most pointed out has been the Organization for the Defense of the Indigenous and Peasant Farmer Rights (OPDDIC), an organizing body close to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). In a communiqué they sent out in November of 2006, OPDDIC members stated, “We demand the immediate evacuation of the territories that have been occupied by the EZLN support base (…), if this does not happen, those holding titles to these lands will take the necessary measures to recuperate land that legitimately corresponds to them.”

In March, OPDDIC leader, Pedro Chulín Jiménez and at least 25 of its militants were detained by the State General Prosecutor (Fiscalía General) to clarify the alleged aggression and retention of three journalists. Eight of them have been held under house arrest and the organization has appeared to lower its profile.

Generally speaking, in the last months, conflict has increased in the “recuperated lands” taken over by the EZLN support bases after the armed uprising in 1994. The area includes between 500,000 and 700,000 hectares. The agrarian problem in the state of Chiapas is nonetheless much broader.

A model case: Last November 13th, 2006, there was an attack against the community known as Viejo Velasco in the municipality of Ocosingo. According to the testimony of the victims, this act of aggression was perpetrated by community members of Nueva Palestina, as well as, persons dressed in public security police uniforms. The incidence ended with four deaths, 4 disappeared persons, and the forced displacement of over 30 persons.

Since then, authorities have been denounced for not carrying out the necessary investigations to locate the disappeared persons. On July 6th of this year families of the victims and a civil observation commission found human remains and clothing of at least two persons. The clothing indicated that they belonged to the two disappeared persons, for which there could be a total of 6 murdered in the incidence.

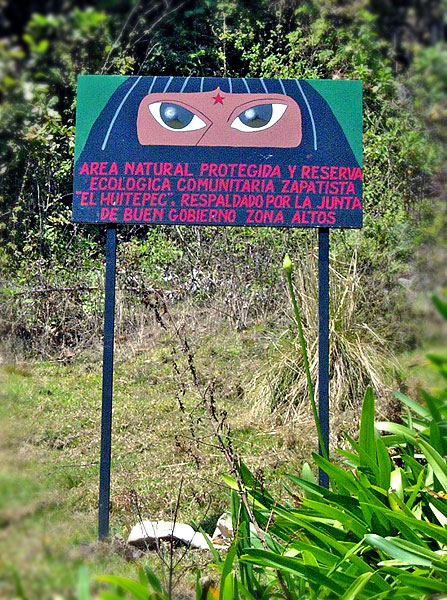

In another case, the Junta of Good Government (JBG) of Los Altos, since September of 2006, announced that “because their concerns went unheard and instead they were pursued and imprisoned [by authorities], Zapatista supporters from the community ‘Huitepec Ocotal segunda sección’ [located close to San Cristóbal] has proposed declaring 103 hectares as the Zapatista Community Ecological Reserve. At almost the same time, the official creation of the Huitepec-Alcanfores Nature Reserve, which includes the 103 hectares of the Zapatista ecological reserve, was announced. To reinforce Zapatista control of the zone, the Junta of Good Government called for the installation of civil observation camps.

The Center for Human Rights Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas indicated that the government did not fulfill the recommendations concerning the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Indigenous peoples made by the Special Rapporteur, Rodolfo Stavenhagen, who in December of 2003 stated: “The creation of new ecological reserves in Indigenous regions should only be done with the previous consultation of affected communities, and the government should respect and support their decisions and the right of Indigenous communities to establish in their territories community-based ecological reserves.”

Another reoccurring issue in local organizing efforts has been around high electricity tariffs. In June, more than two thousand Indigenous and peasant farmers, and adherents to the Other Campaign from municipalities around the border, jungle, and the highlands of Chiapas, marched in the city of Comitán to protest the “repression” that the Federal Commission of Electricity (Comisión Federal de Electricidad) exerts against those who refuse to pay as a form of resistance. They belong to the State Civil Resistance Network Voice of Our Heart (Red Estatal de Resistencia Civil La Voz de Nuestro Corazón).

Oaxaca: new confrontations are a reminder that the social-political conflict in the state continues unresolved

In March, the final report of the International Civil Commission for the Observation of Human Rights (CCIODH) affirmed that security operations implemented in Oaxaca at the end of last year did not have the objective of re-establishing order in the state after the prolonged social conflict began in 2006; instead they “went beyond, seeking to cause social paralysis and immobilization.” In a press conference, they pointed out it is “naïve to think that the conflict is resolved,” and warned that “postponing justice could unleash new violence.”

Simultaneously, the Ombudsman for the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH), José Luis Soberanes, recognized that grave human rights violations (torture, arbitrary detentions, legal failures, and the death of at least 20 persons) occurred during the most tense moments of the social conflict, asserting that the conflict “even though unresolved, has a solution that has been put off, and continues to boil with the potential of a more violent social explosion.”

However, the issue has ceased to be front-page news for now. On June 14th, a year after the beginning of the conflict, the Popular Assembly of the People of Oaxaca (APPO) concluded a massive march without incident. Representatives of Section 22 of the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE), a key actor in the APPO, accused the Secretary of Interior of not responding to their list of demands, already accepted by the previous government, and of avoiding responding to their demands to dismiss Ulises Ruiz.

In the face of this manifestation, Governor Ulises Ruiz assured that the situation in the state is normal, now that protests are a daily part of life and the conflict that erupted in 2006 has been overcome: “Oaxaca with its normal problems, with its daily problems, with its draw-backs and demands, is a state that functions, is a state in peace.”

The federal government also distanced itself from the governor. The Secretary of Interior, Francisco Ramírez Acuña said that mobilizations and demands of the APPO are the exclusive responsibility of Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz. “We have fulfilled our responsibilities in full; it is now Governor Ruiz’s turn to resolve [the conflict] in time so that it does not reignite.” A few days later, the nation’s Supreme Court agreed to investigate possible violations of individual rights in light of the conflict in Oaxaca last year.

On the 16th of July, a week before the commencement of the traditional festival the Guelaguetza, violence erupted once again in Oaxaca: during more than three hours, members and sympathizers of the APPO confronted municipal and state police, leaving at least 40 persons injured on both sides, two seriously, and 60 detained.

As a result of the events, the APPO demanded that the Secretary of Interior reinstall a “table of dialogue” to deter the “new repression campaign” and solve the conflict. While the resignation of the Governor of Oaxaca, Ulises Ruiz, is at the top of demands for the APPO in the negotiating process, the federal government responded that, “it is not in the hands” of the Secretary of Interior. A few days later, a silent march was held with the participation of thousands of Oaxaca’s residents without any incident despite a great police mobilization.

On Monday the 23rd, the first day of regional festivities, the “official Guelaguetza” was held in the middle of a virtual siege. Erangelio Mendoza, Council member of the APPO, asserted “Only with police and transport could they bring people to the Guelaguetza auditorium.” Simultaneously, in the streets of the capital’s center, thousands of people demonstrated once again. Demonstrators denounced the climate of intimidation and the continued repression of the APPO with new illegal detentions. Members of APPO detained two military soldiers during the march, obligating them to walk barefoot before turning them over to the Red Cross. A caravan of teachers that departed from Mexico City to Oaxaca was also intercepted by state police who impeded their arrival to the city.

Even though there was no confrontation on this day, there are fears that violence may spring up again. It is worth emphasizing that state elections in Oaxaca will be held on August 5th, another event that may provoke new tensions. On the other hand, signs of possible links between the APPO and the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR) could be used to justify repressive actions on a larger scale.

Notes:

- Cooperation proposal that seeks to intergrate the Meso America Region in order to promote its integral development. (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- Article from the end of February (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)