ANALYSIS: Mexico: growing polarization

30/05/2008

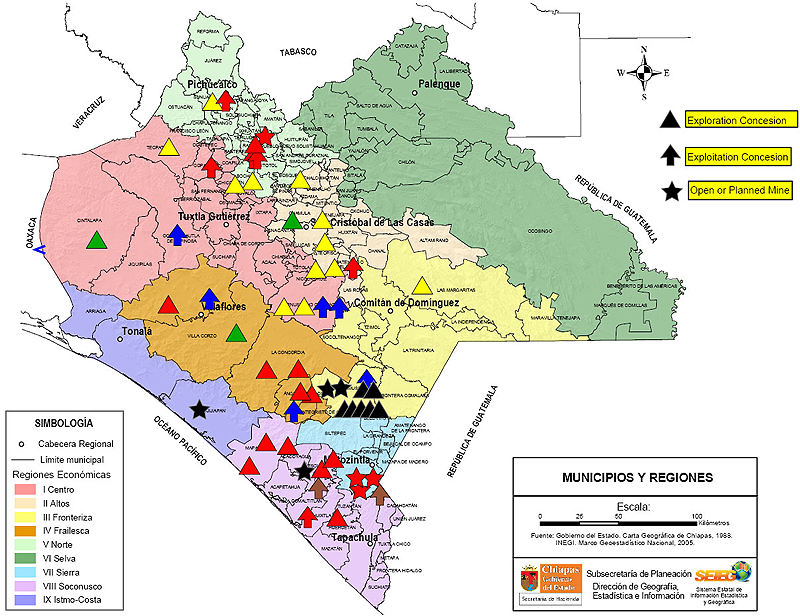

IN FOCUS : Mining in Chiapas – A New threat for the survival of indigenous peoples

29/12/2008In the last few months, the major concern of the Mexican population has revolved around the increase in the prices of basic foodstuffs. Since April, civil organizations, headed by Food First Information and Action Network, Mexico section, warned that the country is showing signs of a food crisis such as that suffered by at least 37 other nations in accordance with the parameters set by the Unite Nations. It is a high-risk situation due to the importation of basic foodstuffs, which now composes 35% of the overall consumption in the country.

A preliminary diagnostic prepared by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) made public in June and titled “Food Prices, Poverty and Social Policy in Mexico,” states that, in the last two years there has been an increase of 1 million 300 thousand people living in poverty (in which individuals are unable to satisfy necessities such as housing, transportation and clothing) and 1 million 800 thousand more Mexicans are now classified as living in extreme poverty.

Within this same time frame, an even more alarming report published by the Chamber of Deputies Center for Public Finance Studies (Centro de Estudios Finanzas Públicas de la Cámara de Diputados) prepared a study named, “Impact of the increase in food prices on poverty in Mexico.” It concluded that the number of Mexicans living in extreme poverty rose to at least 7 million people due to the rise in food prices, increasing the percentage of the total national population from 13.7 to 20 percent.

The governmental responses were strongly questioned by social actors. In late May, agrarian leaders stated that the steps to be taken in terms of familial economic support as announced by the government were “demagogic,” “insufficient” and “ineffective.” They pointed out that the lifting of tariffs, which was part of the plan, would have little effect in reducing the prices of agricultural products as the majority of imports come from the United States and as such are already not subject to tariffs.

In mid June, legislators, union leaders and campesinos considered the control of the prices of various foods, as announced by President Felipe Calderón, were also “insufficient” and above all “late,” since the majority of the present prices already included the raised prices that they had been meant to control.

Energy Reform: latent conflict… for now

Another topic that has continued to have a strong media presence is the controversial energy reform presented by President Felipe Calderón on April 9. According to those in opposition to the reform, the plan implies a privatization of the national petroleum resources. The fact that the Senate decided to organize more than two months of open debates, with the participation of experts, before making a decision on the reform, allowed for a slight reduction in the tension that had been generated around the subject.

The National Democratic Congress (CND), headed by the ex-presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and the Broad Progressive Front (FAP, which is a coalition of the principle leftist political parties in Mexico including the Democratic Revolutionary Party, PRD; the Labor Party, PT; and Convergence, Convergencia) decided to organize a public consultation on the energy reform which took place July 27 in 9 states and the national capital. Both the Senate and the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) had refused to participate in the consultation. The following day the coordinator of the consultation, Manuel Camacho Solís, stated that the consultation had been a “success” as more than one and a half million people participated, of which slightly more than 80% stated that they were against the reform presented by the administration.

The Secretary of Energy, Georgina Kessel, stated that the results only confirm the information that is already available. She added that the consultation affirmed the results that were expected with a smaller turnout than anticipated and various irregularities. She also stated that, “there is an enormous quantity of surveys that have been carried out on a national level which tell us that there is a majority of Mexicans that are in favor of a reform to the national petroleum company (Pemex), and who want to modernize our state company.”

Questions regarding the consultation have come not only from the government or the right, but also from some sectors of the left which have commented that the PRD would lose credibility organizing the consultation without being able to resolve its internal elections within the party (which took place in March). According to the same critics, while recognizing the value of an open consultation process, the PRD’s internal issues could explain the low turnout rates.

The reform has yet to be decided upon in the Congress and the CND and FAP could again take up civil and pacific resistance to it.

Human Rights: A lack of “commitment”?

One of the most noteworthy events in terms of human rights took place in May when Amérigo Incalcaterra, the representative of the UN High Commission on Human Rights (OHCHR) in Mexico, left his position supposedly due to pressure from the Mexican government. According to the Spanish daily El País, the critical attitude of Incalcaterra in the last two years “made the authorities uncomfortable to the point that the situation became intolerable.” It is interesting to note that this information became public shortly after an agreement was to take effect between the OHCHR and the Mexican government, supposedly allowing for greater participation and greater critical power in the investigations carried out by the organization in terms of the human rights situation in Mexico. Various national human rights organizations have asked the government to clarify the situation, a request that has, as of yet, gone unanswered.

In late May Amnesty International (AI) pointed out that the Mexican people continue in their hopes that Felipe Calderón will take a leading role in the defense of human rights. However, in 18 months of the Calderón administration, “it has yet to demonstrate a full commitment in advancing protections” for human rights which is considered “worrisome.”

The principle complaints have to do with increased militarization, which has marked the administration from the very beginning. So far, during the Calderón presidency the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) has received 634 complaints against the Mexican Army for presumed abuses and violations of fundamental rights, with a significant rise in the frequency of complaints. Even so, the second general inspector of the CNDH, Susana Pedroza, seemed to minimize the situation stating that the complaints were not as serious as those registered in 1997.

In May, representatives of Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) maintained that the action taken by the CNDH when faced with the complaints against the military was a “limited” response which did not take into account international standards on the matter.

In July, the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center (Center Prodh) presented a preliminary report that covers the period between January 2007 and July 2008, in which they denounce close to 50 cases of supposed abuses committed by the by elements of the armed forces, mainly in the states of Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Chihuahua, Guerrero and Sinaloa. They report the deaths of 11 individuals due to military actions in 2007, while in 2008 (as of June 10) another 11 deaths were registered. Among the abuses most frequently encountered are physical aggression and fire arm attacks at road blocks or near military barracks.

From Acteal (Chiapas) to Atenco (State of Mexico): the shadow of impunity looms

In late May the civil organization Las Abejas confirmed that the public prosecutor for their case, Noé Maza Albores, threatened the directors of Las Abejas with imprisonment if they did not put a halt to the public denunciations they issued on the 22nd of each month in commemoration of the massacre of 45 indigenous people on December 22, 1997.

In addition, relatives of the 33 indigenous prisoners from Chenalhó, accused of participating in the massacre at Acteal, began a sit-in in Tuxtla Gutiérrez (the capital of Chiapas) in June, requesting a revision of their cases by federal judicial authorities. According to their version, only a dozen of the 78 individuals detained actually participated in the massacre. They maintain that all of the accused were sentenced in criminal proceedings filled with judicial irregularities. In June, more than 10 years after the massacre, the case of those sentenced has been taken up by the National Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN) which has the power to make a decision on the possible irregularities.

Two years after the police operation that repressed a demonstration in San Salvador Atenco, on May 3 and 4 of 2006, Amnesty International has once again demanded justice for the women who were raped during the operation and pointed out that the “serious cases of torture” that were committed are “a sign of the insufficient commitment on the part of the Mexican government to end these crimes and violence against women.”

A few days before the two year anniversary of the events in Atenco, 11 of the 26 women who were assaulted and raped by police enforcement officials during the operation presented a petition before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The Catalan woman Cristina Valls also brought a lawsuit before the National Court of Spain for torture against the police and Mexican authorities that participated in the operation. In July, a judge (magistrado) refused to hear the case. Valls has decided to appeal the decision.

In an interview in May, the governor of the State of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party) denied that the repression in Atenco was a “burden” for his government, and stated that he would again act in the same way if needed to reestablish order and societal peace. In response to international criticism in terms of human rights, he said that “the same will and disposition remains” in his government to clarify the events currently being analyzed by the National Supreme Court of Justice.

Chiapas: intensification of police and military operations

Since the second half of May the police and military operations in indigenous regions of Chiapas have intensified to a level not seen since the late 1990’s, especially, but not exclusively, in zapatista communities located in the Selva and Northern Zones of the state. The Fray Batolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) denounced “a counter-insurgency logic” in which the military and police operate “in tactical deployments in territories with civilian population that are organized around just social demands” and that “also allows them to observe the response of the population to such operations.”

According to the Center for Political Analysis and Social and Economic Research (CAPISE), the aforementioned operations represented “threats of repression, imprisonment, dispossession of property, eviction from their land or death made against the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), Zapatista communities, and members of the Other Campaign.“

Jorge Lofredo, of the Center for Documentation of Armed Movements, while presenting Corte de Caja, a recently published book by Laura Castellanos and Ricardo Trabulsi that consists of an ample interview with sub-comandante Marcos, referred to one of Marcos assertions, “We are in the same situation as in 1993, except in reverse. (…) Now it is the government that is preparing the attack.” Lofredo emphasized in the same presentation: “Although they have reiterated denunciations in regards to military incursions in the Zapatista zone that have not been solidified, it could be considered the execution of a military strategy that resides precisely there: constant sieges or the threat thereof, in which they speculate that with the constant reaction of the EZLN and non-governmental organizations they will be discredited or will create an indifference, leading to a suicidal end.”

In early July, given this situation, more than 200 collectives from various parts of the world demanded a cease to aggression against the Zapatistas. In late July, some 300 activists, principally from Europe, arrived in Chiapas to monitor and denounce a situation which they consider forms part of a “war scenario.”

Finally, it is important to note, especially from the perspective of the connection that has been mentioned between economic interests and militarization, that June 28 saw the conclusion of the Tenth Tuxtla Gutierrez Summit of Heads of State and Government (including the heads of State from Mexico, Central America and Colombia) which took place in Villahermosa, Tabasco. The leaders present reaffirmed the objectives of the Plan Puebla Panamá which was subsequently renamed the “Mesoamerican Project.” The final declaration makes repeated reference to the fight against organized crime and adherence to the Merida Initiative, which is financed by the United States.

… … … … … …

Police and military operations: Principle cases

- On April 27, at least 500 police agents violently entered the community of Cruztón, municipality of Venustiano Carranza.

- On May 19 and 20 a military incursion aided by the Federal Investigation Agency took place in the community of San Jerónimo Tulijá (within the official municipality of Chilón and the autonomous municipality of Ricardo Flores Magón).

- On May 22 armed forces carried out a patrol of 11 communities in Venustiano Carranza where there is a presence of the Emiliano Zapata Campesino Organization-Carranza Region (OCEZ-RC).

- On May 23, in various communities located in the municipality of Tila (Northern Zone), several military check points were installed. The same day, circling aircraft were noted and an incursion took place in Carrizal y Río Florida (municipality of Ocosingo).

- On May 27 the Federal Attorney General for Environmental Protection reported that, with asístanse from the Federal Police, the Federal Attorney General, and the Mexican Navy, they evicted two campesino groups that had settled on 35 hectares in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve in an irregular manner.

- On May 29 the National Front of Struggle for Socialism (FNLS) reported the presence of circling helicopter gunships over communities belonging to the Emiliano Zapata Campesino Organization (OCEZ).

- On June 4 military and police incursions reportedly took place in the vicinity of the Zapatista caracol La Garrucha as well as in the zapatista communities of Hermenegildo Galeana y San Alejandro.

- On July 17 military personnel circled the community of 28 de Junio, in the municipality of Venustiano Carranza, where they remained for three days. They claimed they were looking for fields planted with drugs ; however, they appeared to be looking for members of the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR).

- On July 23 the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center reported that state police had assaulted campesinos from the community of Cruztón in the municipality of Venustiano Carranza, as well as observers belonging to the Other Campaign.

… … … … … …

Chiapas: other points of tension

Various parts of the state continue to experience alarming situations. In the Highlands in May, the autonomous zapatista council of Magdalena de la Paz and the Good Government Council (JBG) of Oventic denounced an attempt to seize a portion of their territory. In Huitepec threats of the dismantling of the Zaptista ecological reserve located in the area remain. In June a group connected to the municipal government attempted to plant trees in the reserve. In July residents of Section III Las Palmas, as well as those in Huitepec, confirmed that the municipal government of San Cristóbal was trying to compel them to back a forced dismantling of the reserve.

In the Selva Zone due to a dispute over water and electricity in May, members of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and zapatistas confronted each other in the community of Morelia, the seat of another Zapatista Caracol, in the official municipality of Altamirano, resulting in at least 10 wounded.

Another point of contention continues to be the high price of electricity. In April, members of the Peoples United in Defense of Electrical Energy (PUDEE) from several municipalities of the Northern Zone of Chiapas continued to denounce the fact that the government has required people to show proof that they have paid their electricity bill in order to receive government services. In July more than one thousand indigenous people participated in a march in Ocosingo demanding that the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) implement just prices for electricity, the cancellation of all debts and an end to the cutting of electrical service.

With regard to the organizational process initiated in various prisons in March and April of this year (see previous SIPAZ report), in early June the zapatista prisoners, Ángel Concepción Pérez Gutiérrez and his father Francisco Pérez Vázquez, were released after 12 years in a prison in Tacotalpa, Tabasco. In late July, three members of the inmate organization “La Voz de Los Llanos,” were released from the State Center for the Social Reinsertion of Sentenced Prisoners (CERSS) n.5 near San Cristóbal de las Casas; as well as three other prisoners from the inmate organization “La Voz de El Amate” who were being held in the CERSS n.14

Dialogue between the EPR and the government: large media coverage, few results

In late April, the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR, an armed group with origins in the guerilla movements that arose in southern Mexico some 40 years ago) called upon various Mexican public figures to form a mediation group that would permit them to enter into an indirect dialogue with the federal government in order to obtain proof of life in the cases of two of their members, Edmundo Reyes Amaya and Gabriel Alberto Cruz Sánchez, both disappeared in Oaxaca in May of last year. The aforementioned public figures agreed to participate in the mediation process given that the EPR agreed to accept certain conditions set by the mediation commission, including the immediate suspension of all armed activities

Negotiations seemed improbable when the federal government added their own conditions to the dialogue: a direct meeting with the EPR (in which the mediators would take on a “witness” role in the negotiations); a public declaration on the part of the EPR to definitively suspend all “radical activities” that include sabotage and violence; and an agreement that the dialogue would not be exclusively tied to the disappeared members of the EPR, but would include negotiations in regards to a decisive end to the armed struggle.

The writer Carlos Montemayor and the anthropologist Gilberto López y Rivas, both put forward by the EPR to participate in the mediation, pointed out that in order for the proposed talks to achieve success it was imperative that the Secretary of the Interior understand “that when a guerrilla force opens a political negotiation, they are not proposing their own capitulation.” They also rejected the notion of being “convidados de piedra” which means “invited to play a silent role” at the negotiating table as “witnesses.” Through a communiqué, the EPR warned that there would be no “dialogue or negotiation which would signify an unconditional surrender, much less one that would imply a giving up of armed struggle in order to incorporate into the institutional life.”

The federal government finally agreed to hold meetings with the mediation commission on May 13 and 20. According to Montemayor, when “the members of the commission made proposals in greater depth, for the first time, on the political and procedural aspects of the issue,” the press maintained “an unexpected silence” after all of the media attention that the event had attracted.

Part of the difficulty and distinctions between the federal government and the mediation commission is that the commission felt that they needed to put together the legal requirements necessary to typify the forced disappearance of persons, an aspect that would put another series of responsibilities in front of the State. In an article published in the Mexican daily La Jornada, Montemayor emphasized the fact that the “protracted sequence of frustrating and ineffective lawsuits could suggest, in the context of international legislation, the shaping of one of the principle aspects that typify the crime of forced disappearance of persons,” according to the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons, which the Mexican government signed onto in 2001.

After the initial dialogue process, investigations have continued, surrounded by rumors and speculation as to the participation or lack thereof on the part of officials of the Attorney General’s Office in Oaxaca as well as the army without having come to any conclusions as of yet. In a new communiqué circulated in June, the EPR warned the federal government that “the time is short” for them to produce the proof of life of their members and pointed out that “there are [indeed] forced disappearances” in Mexico and, according to the organization, there exist at least 75 current cases.