SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (From mid-November 2013 to mid-February 2014)

21/02/2014

IN FOCUS: Thinking of another justice

21/05/2014One of the most relevant happenings in the past months has been the arrest of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, “El Chapo,” the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, which is considered to be one of the most important organized crime groups in the world. However, according to experts, this arrest does not imply a definitive strike against organized crime, given that El Chapo’s successor already has replaced him. In addition, they recall that when he was arrested in 2001, this had little impact on the cartel’s activity or on the operational capacity of El Chapo from prison. Furthermore, he escaped from a high security prison, something that would be possible only with assistance from State authorities – a scenario that can be expected to be repeated. Lastly, the fragmentation of the cartel does not necessarily open the door to a more hopeful context with regard to insecurity. On the contrary, indeed, it could reopen a struggle for power, particularly in several states of northwestern Mexico.

While this arrest can be considered a success, some analysts fear that it will reinforce the militarist and authoritarian model adopted by the federal government which has had negative impacts on other aspects of social life. These analysts indicated that both at the federal and state levels, legislation has been passed that could restrict the exercise of some human rights. According to the Front for Freedom of Expression and Social Protest, a platform founded in April, there exist at least 13 bills that are cause for concern in this sense.

The first example of this was an increase in protests against legislative proposals to reform the telecommunications regulations passed in 2012. Among the criticisms raised by protestors is the idea that the reform would promote censorship, violate the right to privacy of users, and threaten net neutrality. On 22 April, a march in Mexico City was repressed. The Front for Freedom of Expression and Social Protest affirmed that “the new aggressions against representatives of media, activists, human rights defenders, and representatives of the Commission of Human Rights of Mexico City are reasons for concern.” These protests have begun to spread to other states. As a second example, the Senate in April approved regulatory laws to re-examine the process whereby a state of emergency is declared. Civil organizations expressed their opposition, noting that “This should be reviewed and changed, because we are concerned that there is a tendency to legalize repression and to criminalize social protest.”

As an exception to this trend, the Senate also in April unanimously approved a reform to the Code of Military Justice limiting military tribunals in cases in which members of the Armed Forced commit crimes against civilians, stipulating that they must be tried in civil courts, not military ones. This reform is a response to the demands and recommendations made by Mexican and international human rights organizations for the last 8 years.

Lastly, in April the National Program on Infrastructure (PNI) for 2014-2018 was approved, backed by an investment of 7.7 billion pesos. It would especially impact the southern and southeastern regions of the country, where 189 projects are sought to increase tourist, agro-livestock, energy, and industrial potential. It should be stressed that some of the projects announced within the PNI have generated rejection from the populations that will be affected by their development, such as, among others, the construction of the Paso de la Reina dam or wind energy farms on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, and the highway between San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque. These projects have been repudiated by local communities and organizations due to the grave impacts they could have such as loss of lands, environmental degradation, or forced displacement, given the lack of respect for the rights of local peoples to be informed and consulted previously about any administrative or legislative decree that could affect them.

Mexico continues to be monitored on the international stage in terms of human rights

In February, Salil Shetty, General Secretary for Amnesty International, visited Mexico. He deplored that in the country human rights are not “a priority, particularly in the agenda of the president”: “In the last five or six years we have seen a regression […] and some of the data even indicate a crisis.” The official expressed his concern regarding forced disappearances “which have taken tens of thousands of lives in the last decade,” the vulnerabilities faced by undocumented migrants, and the continuous aggressions against journalists and human rights defenders. Shetty lamented “the near-total impunity of these crimes and the infiltration of organized crime in the security forces.”

This diagnosis coincided in large part with that of Mexican human rights organizations, as was exposed in Belgium in March at the Fourth High-Level Dialogue on Human Rights between Mexico and the European Union. There, organizations denounced that in Mexico “there is a context of violence and impunity that has led the country to an unprecedented humanitarian crisis.” They stressed that “the statistics on abuse speak of a systematic and generalized violation of human rights on the part of the police, soldiers, and public officials, who commit arbitrary arrests, torture, forced disappearances, and extrajudicial executions, among other violations; public and private actors who commit acts of violence and discrimination against women; and Mexican and transnational corporations that pollute, displace populations, and exploit natural resources without consulting the affected peoples and communities.”

Upon ending his visit to the country, Juan E. Méndez, UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, affirmed that torture is a “generalized phenomenon” in Mexico. He noted impunity and the regular use of torture by security forces as a “means of criminal investigation” to obtain confessions as great problems in this sense. He expressed his concern for the continued militarization of various regions of the country, in addition to the persistent participation of military personnel in civilian security forces.

Nearly two years after its creation, the Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists in Mexico found itself in a delicate moment, in light of the resignation of its head in March. Civil councilors of the Mechanism retired from the Governmental Council, given their view that there do not exist adequate conditions for its functioning. They identified a number of structural failures: the impossibility of having a stable and qualified team due to constant firings and a delay in attending to cases (70% of petitions presented had not been attended). Víctor Manuel Serrato Lozano has been named the new head of the Mechanism. From the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH), he has participated as a member of the Governmental Council, which he now heads.

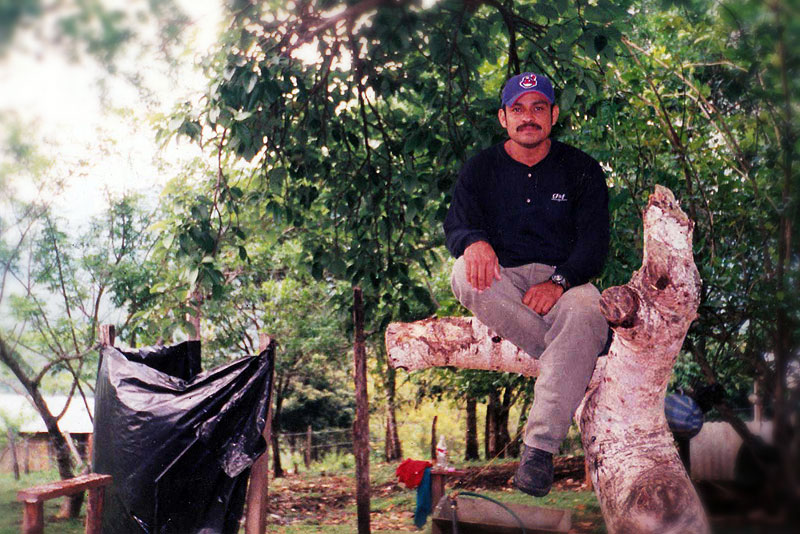

Chiapas: EZLN on alert after murder of one of its support base members

On 2 May, members of the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM), the National Action Party (PAN), and the Historical Independent Center of Agricultural Workers and Campesinos (CIOAC-H) attacked support bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (BAEZLN) in the La Realidad ejido, Las Margaritas municipality (official), governing seat of a Zapatista Caracol (autonomous region). As a result of the attack, the Zapatista support base member José Luis Solís López (known as Galeano) died and fifteen other Zapatistas were injured. Since the previous day, a dialogue process had been opened between the Zapatista Good Government Council (JBG) at La Realidad and a member of the Historical CIOAC to resolve the appropriation by the CIOAC-H and political party members of a vehicle that belonged to the JBG. The CIOAC-H argued that the JBG had arrested its secretary, a charge that was in fact denied by the person in question. The JBG unequivocally clarified that the event was an attack rather than a confrontation between the two groups.

On 8 May, the EZLN published a communiqué announcing that the activities it had planned for the end of May with indigenous peoples of Mexico will be canceled, including an event in homage to Don Luis Villoro Toranzo and the “Ethics in the Face of Looting” seminar. The communiqué explains the reasons for declaring a state of alert: “the primary results of the investigation, in addition to the information which is reaching us, leaves no room for doubt: […]. This was a planned attack.” Another communiqué announced the continuation of threats against support bases in La Realidad and the plans to carry out an homage to José Luis Solís López on 24 May in all the Zapatista Caracoles. Several civil organizations and solidarity groups have denounced the attack on the Zapatista autonomous project. Despite declaring itself on alert, the EZLN affirmed that “our efforts have been for peace, while their efforts have been for war.”

Human rights agenda: many tasks remain

The visit to Mexico of the UN Special Rapporteur on torture has been one of the most-covered events. A recent example has been the death of a youth in the Acala municipality after his detention by municipal police. The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC) stated that “it is aware of two other cases of death while in custody in 2014 […] in Tapachula […], which shows the recurring pattern of police action.” Subsequently, the indigenous prisoners Audentino García Villafuerte and Andrés and Josué López Hernández were released. According to denunciations made by human rights organizations, the charges against these three were fabricated and they were subjected to torture during their imprisonment. The CDHFBC affirmed that “in the prisons of the state of Chiapas, indigenous peoples are discriminated against and abused, but due to fear of reprisals against them and their families, they do not denounce the acts of torture or other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. Furthermore, even when torture is obvious, justice is absent because it is not investigated.”

In a parallel to the national debate, in May the state congress of Chiapas approved the initiative to reform the Code governing the legitimate use of public force. The change has been considered by human rights defenders and opposition legislators as “yet another regression in terms of human rights” in Chiapas.

With regard to human rights defenders, in March there were denunciations of harassment suffered by lawyers of Strategic Defense for Human Rights, Leonel Rivero Rodríguez and Augusto César Sandino Rivero Espinoza. These attorneys are known for their interventions in cases such as that of now ex-prisoner Alberto Patishtán (Chiapas) and communal police from Michoacán. In addition to death threats communicated in person and by phone in Michoacán, in March the office that Rivero Rodríguez maintains in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, was ransacked.

An omnipresent question in terms of human rights has been forced displacement. Beginning in April 2013, a dispute started over land on which a Catholic chapel was located in the Puebla Colony, Chenalhó municipality. For this reason, 17 families – not all of them Catholics – were displaced. In February, the state government turned over the disputed plot of land to the Catholic diocese. However, the possibility of return was delayed first by the burning of the entrance door to the community catechism building, and then by arson against the home of two of the displaced. Two persons were arrested for these acts, but the displaced families believe that they are not the responsible ones. They finally returned to their homes on 14 April, calling the move a “return without justice.” Eduardo Ramírez Aguilar, Secretary General for Governance, warned that if the problems continued, “what will follow is not dialogue but instead application of the law.” The Las Abejas Civil Society, to which the vast majority of the displaced in fact belong, has noted that it will not accept this “climate of injustice” but will continue denouncing and seeking out “true justice.” In other cases, the displaced from Banavil (Tenejapa municipality) and Aurora Ermita (Pueblo Nuevo Solistahuacán) publicly denounced the conditions in which they find themselves as well as the lack of response made by the authorities.

Lastly, several activities were organized on 8 March for International Women’s Day. The members of the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women and Femicide have declared themselves “on permanent popular alert.” In April, they denounced the release of two presumed murderers of women and accused the State of being complicit with the femicides, noting that the number of cases continues to rise.

Land and territory: between attacks and accords

In March, Carlos Gómez Silvano, adherent to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, was murdered in the Chilón municipality. On 26 April, ejidatarios carried out an homage to their leaders who had “fallen in defense of their people and territory.” They indicated that “the three levels of government […] do not cease their attacks and lootings by means of lies and tricks, death threats, violence, imprisonment, torture, and even murder, all of which they employ to realize their ambition of taking control of the communal lands of the ejido for the construction of a luxury tourist complex beside the waterfalls of Agua Azul.”

In addition, in April a “historic” agreement was reached between the Lacandón Zone Community and the ARIC UU-ID (Rural Association for Collective Interest-Union of Independent and Democratic Unions) that would permit the recognition of three communities located in the Montes Azules biosphere reserve or its surroundings. A presidential resolution from 1976 provided the Lacandones with 614,000 hectares of land. Since that time, other ethnicities who reside in the zone have had to live under constant threat of displacement. This accord is the fruit of a process of dialogue that began directly between both involved parties, without the participation of the government, due to the government’s “lack of will” in resolving the conflict, as ARIC representatives affirmed in a press conference. The State’s position has been to recall that, since the area is a protected reserve, new population centers cannot be authorized, nor can “irregular” settlements be normalized.

Oaxaca: worrying rise in violence

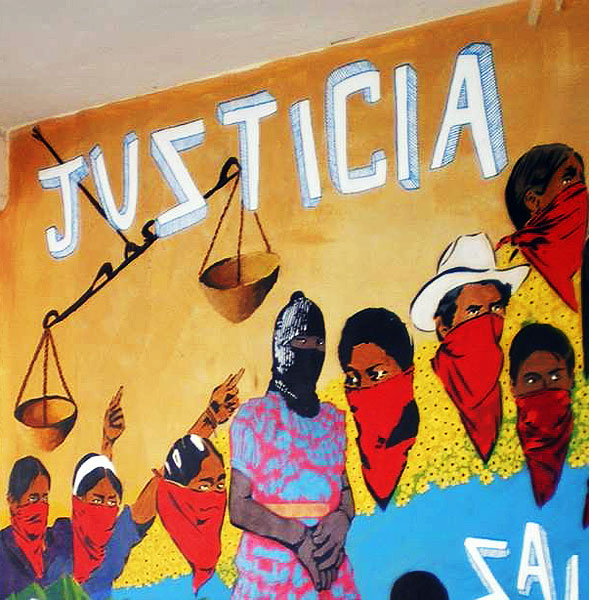

© SIPAZ

A significant increase in the number of cases of violence against journalists, social organizations, and human rights defenders has been noted in the state of Oaxaca. In February, the Democratic Civic Union of Neighborhoods Colonies and Communities (UCIDEBACC) denounced death threats directed at its spokesperson as well as attacks against two other members who were injured by the Preventive Police while participating in a peaceful protest. In March, the State Preventive Police (PEP) proceeded to violently displace members of the teacher training school from the State Coordination for Education in Oaxaca (CNEO), arresting 162 and injuring several others. Another violent displacement took place in March on the land of the Cacalotillo Cooperative of Aquaculture and Fishing in Juquila. Using juridical means, the Cooperative recovered the land more than a year ago, thus confronting economic interests that want the region for tourist purposes. Analysts note that the increase in police violence has coincided with the change at the highest levels of the Oaxacan Secretary for Public Security.

In April, several murders and executions took place in the state, some of them presumably having a political character. Among others, the dead have included an ex-member of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO), the leader of the Freedom Union, two members of the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle (MULT), two teachers from the National Union of Educational Workers (SNTE-CNTE), and a relative of the mayor of San Agustín Loxicha. In May, personnel from different communication media and the organization Article 19 denounced the increase in the number of attacks on journalists, with Oaxaca among the most dangerous states in the country for the exercise of this profession.

In the Isthmus region, death threats and an attempted kidnapping against opponents of the wind-energy project promoted in Juchitán by the multinational energy firm Fenosa Natural Gas have been denounced. Several attacks in the Álvaro Obregón community against members of the General Assembly and the Communal Police have also been reported. In March the Isthmus Region National Indigenous Congress (CNI) was held in Álvaro Obregón, where the principal question was the organization of communities to struggle against wind-energy projects in Tehuantepec.

In observance of the second anniversary of the murder of Bernardo Vásquez Sánchez, the Oaxacan Collective in Defense of Land organized events in Oaxaca, Mexico City, and Chiapas to publicly present its report “Justice for San José del Progreso.” The report gives evidence of the systematic violations of human rights produced by the imposition of the mining project developed by the Fortune Silver Mines firm since 2006. In addition to the impunity represented by the lack of resolution of the murder of Bernardo Vásquez, in observance of the fourth anniversary of the murders of Bety Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola (a Finnish observer) while they participated in a humanitarian aid caravan to San Juan Copala, members of the European Parliament and relatives affirmed that the cases could have been resolved in two months, had the authorities expressed the necessary political will. On 29 April, Omar Esparza, Bety Cariño’s widower, together with relatives and members of civil society, undertook a hunger strike in front of the Federal Attorney General’s Office (PGR) in Mexico City. After sixteen days, they succeeded in having the authorities commit themselves to arresting those responsible and to protecting witnesses of the crimes.

Guerrero: new cases of harassment and impunity

Several acts of violence and harassment against journalists and social and communal organization have been registered in the state of Guerrero. The Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP) denounced the police-military operation carried out in the Concepción community aimed at arresting the spokesperson of the organization, illegally searching homes and stealing belongings, and beating residents. In April, 5 members of the communal police of CECOP (incorporated in March to the Regional Coordination of Communal Authorities-Communal Police [CRAC-PC]) were injured during an ambush carried out by armed civilians working for gravel companies.

In March, a police operation in Tixtla resulted in the detention of Aurora Molina González, the sister of a CRAC-PC leader who was arrested last October. The state government affirms that the CRAC-PC House of Justice in El Paraíso de Ayutla de los Libres has links to guerrilla movements.

Lastly, in April, a march was held in San Luis Acatlán to support the naming of the new coordinators of the CRAC-PC. Protestors called for the rescue of the communal justice system, indicating to the state and federal governments that this was not for sale. This same month, Nestora Salgado García, a communal police officer from Olinalá imprisoned in Nayarit, received the “Don Sergio Méndez Arceo” National Human Rights Prize.

In other news, the CNDH has initiated an investigation into the attacks carried out by Governor Ángel Aguirre Rivero’s security personnel against a correspondent from the daily El Sur .

Once again, some of the cases of impunity which exist in the State have come to light, such as that of the activist Rosendo Radilla Pacheco, who was disappeared by the military in 1974. On the centenary of his birth, relatives and social organizations held a memorial demanding punishment of those responsible. Similarly, the report of the “Light against Impunity” Observation Mission was presented; it denounces that 13 social activists were murdered in 2013 in the state, and that no clarification of these crimes has yet been provided.