ANALYSIS: Mexico – human rights and security, an impossible puzzle?

30/04/2009

ANALYSIS: A Serious deterioration of the human rights situation in Chiapas and Mexico

30/11/2009In the last few months, while Mexico was not the center of international attention for the violence linked to organized crime, it was at the forefront because of the AH1N1 influenza epidemic, due to being the first country to alert of the existence of this virus and to have the most cases of it at that moment. Once the immediate health emergency had been dealt with, even though the virus is growing to date, it exposed three major issues.

On one hand, it has been estimated that the economic impact of the epidemic could reach at least 1% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In addition to the effects on the tourism industry (one of the primary sources of income in the country), the restrictions imposed in order to contain the epidemic affected an economy, which even before the emergency, had the worst unemployment rate since the collapse of 1995. The economic situation could even become more critical because of the reduction in migration to the US, a phenomenon that has served as an ‘escape valve’ in the past. This reduction is not as much due to the increase in US immigration enforcement, but due to the lack of work opportunities in the US, which was the root of the work economic crisis. The media coverage of the war on drugs and of the epidemic has overshadowed the fact that 40% of the Mexican population still lives in poverty. On the other hand, the emergency showed the risks involved in industrial growth of livestock, dominated by transnational corporations, and the structural flaws in the Mexican healthcare system.

Elections in the midst of institutional discredit

It is noteworthy that so many Mexicans have come to doubt the existence of the AH1N1 virus. This skepticism is caused by a large measure of lack of faith in the Mexican institutions. In April, the Secretary of Government released the results of the 4th National Survey on Cultural Politics and Citizen Practices, which revealed that only half of Mexicans consider that they live in a democratic system, and a similar percentage believe that the government would rather impose than consult.

This rift between the people and their representatives is being reflected in various aspects, one of which is electoral. On July 5, the elections for more than 1,500 public figures nationwide were held. The abstention rate reached 55.19% and the null vote was 5.4%. The null vote had generated a significant movement leading up to the election.

Taking into account the low participation, the results show a marked change compared with the last ten years: after almost 12 years of having lost the Chamber of Representatives, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI, the party which maintained power for more than 70 years until 2000) was the clear winner of the election. Of a total of 500 seats, it won 237 representatives. Also on July 5, the PRI won five of the six governorships in dispute.

The National Action Party (PAN, in power now) only received 9,549,000 votes for the Congressional elections (12.3%), which many consider the result of a punishment vote against the government of Felipe Calderón. It is important to remember that in the middle of the controversy of electoral fraud, it was assumed that the PAN had won the presidential elections of 2006 by around 14 million votes. Its federal representatives will decrease from 206 to 143, the same thing will happen to the leftist parties, which is seen as a result of the divisions and internal conflicts: of the 126 representatives before the elections, they will be reduced to 90 (71 for the Democratic Revolution Party, PRD; 13 for the Workers Party and 6 for the Convergence Party).

Militarization: a solution that does not solve the issue

In spite of the critical economic situation aggravated by the influenza epidemic and the electoral results, there is no doubt that the war on drug trafficking continues to be the main priority of the federal government. Following a small reduction in the number of killings, the violence seems to have picked up in the last few months.

Looking at the larger picture, at the end of June, the World Bank released the Governance Indicators, which measures on a scale of 1 to 100, the political stability and lack of violence; Mexico received 24.4 points in 2008, 27 in 2007, and 45 in 2004. In the Rule of Law category (indicating the competence of the government in carrying out and respecting the laws), Mexico received a score of 29.7 in 2008, as opposed to 36.2 the year before, and 42.4 in 2004.

During the health crisis brought on by the influenza, the Congress approved orders dealing with the law of National Security proposed by the President. In April, the Federal Government proposed a group of four reform initiatives on matters of national security, military justice, arms dealing, and organized crime.

It is important to remember that Article 129 of the constitution states, “in peacetime, no military authority can exercise other functions than those directly related to military discipline.” Paradoxically, with the objective of containing “the expansion of organized crime” and “completely” guaranteeing national security, an exception was proposed under which in the case of something that “affects the security of the nation,” the civil authorities could become subordinate to the army. Among the possibilities in which this situation could occur is the case of “uprisings.”

Since the beginning of Calderon’s term, the Armed Forces have become more and more involved in public security tasks, and so it seems that the proposed reforms seek to legalize and normalize these types of practices. The concerns expressed by analysts and human rights organizations have to do with the fact that these reforms could involve the suspension of basic guarantees like freedom of expression, freedom of association, free movement, and the right to due process of law. According to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), during Calderon’s term they have registered more than 1,600 complaints against the Army for crimes like extrajudicial execution, torture, sexual assault, arbitrary detention, and excessive use of force and firearms.

The Military tribunal: a priority for Human Rights organizations

In the last few months, in media outlets on both a national and international level, human rights violations committed by members of the Army have been constantly denounced. They have noted that the levels of these violations in the war on drugs are as high as they were during the dirty war.

At the end of March, in Washington DC, as part of the 134th session of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), a hearing was held on the issue of military justice and human rights. Civil Mexican organizations presented the cases that they have been working on, especially during Calderon’s term. These show that the Mexican State is not complying with international human rights standards. At the end of the hearing, the Inter-American Human Rights Commission (IACHR) released a communiqué which expressed “its concern because a number of countries in the region continue using military justice to investigate and judge common crimes committed by members of the Armed Forces or of the police. The IACHR reiterates that military jurisdiction is exceptional and should only be used for crimes pertaining to its function.”

Last April, Human Rights Watch released a report titled “Uniform Impunity: Mexico’s Misuse of Military Justice to Prosecute Abuses in Counter narcotics and Public Security Operations”. In this report, it pointed out the fact that the military tribunal system actually protects those responsible for human rights violations.

Six of the eight recommendations of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) (see SIPAZ Report Vol. 14 no. 1, April 2009) of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, which were rejected by the Mexican Government, dealt with the necessity of limited military justice.

On July 7, Mexico was forced to appear before the Inter-American Human Rights Court (IAHRC) in the case of the forced disappearance of Rosendo Radilla Pacheco, who was last seen in the old military base of Atoyac de Álvarez, Guerrero in 1974 (a case of forced disappearance from the Dirty War).

On July 8, the First Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice agreed to begin full discussion on the issue of an appeal of military justice. The case in question is the killing of civilian Zenón Medina by members of the Army, which took place in March of 2008 at a military roadblock in Sinaloa and was judged by a military tribunal. The Secretary of National Defense (Sedena) rejected the call for an appeal because it regarded the event as a case of lack of discipline by soldiers in the line of duty.

In the face of international pressure, and although the federal government continues defending the military tribunals, Calderón informed the UN that the military tribunals presently involve six preliminary investigations and that in three cases, 32 investigators were deployed, in addition that in nine rulings, 14 military members were condemned.

In spite of concerns, the US increased aid to the Mexican Military

In the last few months, many high level US officials visited Mexico, including the first official visit of President Barack Obama in April. They did not make any significant announcements regarding issues, which had generated major expectations (business, migration, or security).

Possibly in part because of the US media coverage which presented Mexico as a ‘failed state’; in the middle of June, the US legislature approved a Supplemental Military Spending Bill, which included 420 million dollars for Mexico. This amount represented a significant increase from Obama’s proposal, which had originally been for 66 million dollars. In fact, it replaced and exceeded the funds cut from the first two years of the Mérida Initiative.

Another area of collaboration between the US and Mexico was the participation of the Mexican Navy in the International Anti-Submarine Forces (UNITAS), coordinated by the US Fourth Fleet which was reactivated almost a year ago. Experts consider that the US Fourth Fleet, responsible for Latin America and the Caribbean, along with the Northern Command forms part of a strategic military re-orientation towards Latin America. This process could increase following the military coup, which took place in Honduras on June 27, an event whose geopolitical implications for the region remain to be seen.

From social movements to armed groups: a gloomy panorama

At the end of March, with low expectations following the ruling on the case of Atenco (see SIPAZ Report, April 2009), the full Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) received the preliminary report regarding human rights violations committed in Oaxaca, from May of 2006 to July of 2007. Although once again they established the existence of “grave violations of individual rights,” the commission decided not to point to “those responsible, instead to only identify those who directly participated in the events where grave violations of individual rights occurred.”

Dealing with one of the issues most emphasized by human rights organizations, on April 20 the “International Forum on Criminalization of Human Rights Defenders and Social Protest” took place in the state of Guerrero. In addition to denouncing the general tendencies in the country, the final declaration emphasized the “right to protest because the institutional mechanisms do not efficiently respond to social demands.”

In April, the National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” presented a document which identified at least 41 cases in the last two years where there was police repression, arbitrary detentions, intercommunity confrontations, threats, hostilities, and killings carried out against environmental activists in 13 Mexican states (including Chiapas). It stated that the work of defenders of natural resources in the country is more and more difficult because their actions conflict with the economic interests of the government, local bosses, and transnational corporations.

Another event that could go unnoticed was the enactment of the Manifesto of Ostula, a document approved by indigenous peoples and communities from nine states who attended the 25th assembly of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) in the central Pacific region in the middle of June. Faced with government and paramilitary repression, and neo-liberal policies “of disregard, discrimination, destruction, and death,” they took back the right of self-defense in order to protect their territory and natural resources.

On April 21, the Mediation Commission between the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR) and the Government ended its mission almost a year after it was formed in order to resolve the situation of two militants of the armed group who were considered to be disappeared detainees. It justified the decision by explaining that the “federal government did not have the will to resolve the issue.”

Chiapas: Impunity and “new-old” conflicts

In June, the first American Meeting Against Impunity took place in the Zapatista Caracol (municipal center) of Morelia, with the participation of 15 countries from the continent, in addition to delegations from Europe and Australia. Impunity was repeatedly denounced as an issue in the past and present of Latin America, something that is certainly true in Chiapas. One of the most striking situations in the past months was the resolution of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) to release 12 of those convicted of the Massacre of Acteal, which occurred on December 22, 1997. The Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (CDHFBC) expressed fear “that the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, in this decision is contributing to the impunity, with irreversible consequences for the indigenous communities of Chiapas where the Internal Armed Conflict persists.”

At the end of March, a special office for the Protection of Non-Governmental Organizations for the Defense of Human Rights in Chiapas was created at the initiative of the State Executive, after accepting the recommendation of the National Commission of Human Rights (CNDH), in order to deal with delays in justice regarding the aggressions against the CDHFBC which occurred in October of 2006. Nevertheless, newly these types of aggression appeared not to be just things of the past when in June of this year a renewed tendency of harassment against Human Rights Defenders in San Cristóbal de las Casas was observed.

On the other hand, the majority of the reactions to social organizing efforts, which led to repression, are linked to issues of “land and territory.” Although many of the cases have to do with decades-old, unresolved land disputes, there are also still cases involving Zapatista “recuperated lands” following the armed uprising. Other focal points of conflict have to do with a wider definition of territory. We will give just three examples:

Highways and Eco-tourism projects

At the beginning of June, construction began in San Cristóbal of a highway which will unite San Cristóbal to the equally tourist attraction community, Palenque. This construction, as well as the expansion and internationalization of the airport in Palenque, is part of the completion of the Planned Integral Center of Palenque- Agua Azul (CIPP), which is being presented by the State Government as the “first eco-archeological development project in the country”.

The population’s rejection of these projects has multiplied, particularly in the community of Mitzitón, in the municipality of San Cristóbal, and in San Sebastian Bachajón. At the beginning of July, five of the seven indigenous tzeltales, members of Bachajón, were freed from prison after being detained last April in distinct police actions. They denounced that they had been tortured and forced to confess to participation in assaults on the highway between San Cristóbal and Palenque. The CDHFBC explained their detention, saying, “The people of the ejido of San Sebastian Bachajón, Adherents to the Other Campaign, are part of an indigenous movement which opposes neo-liberal plans to steal their territory and exploit its natural resources. For many years, the region of Agua Azul has been a tourism zone which has been cared for and used for the benefit of the tstelal people of Bachajón”.

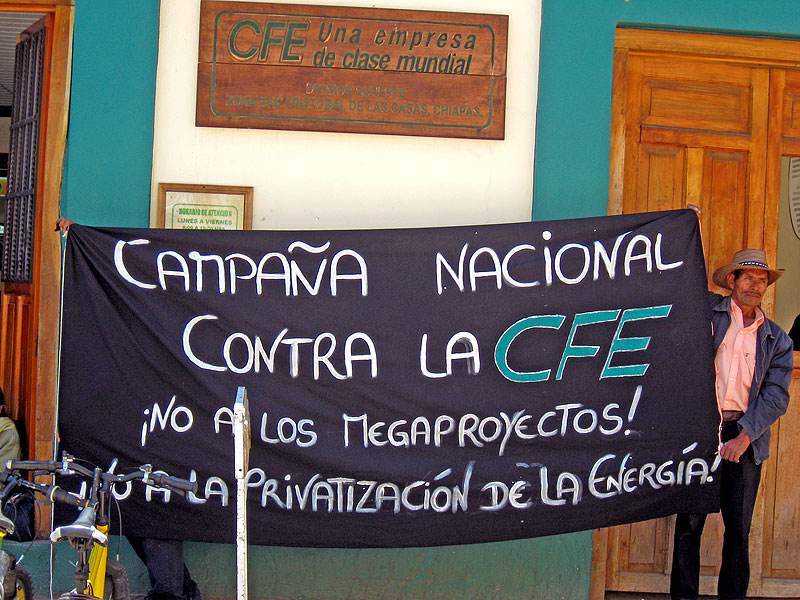

High Electricity Prices

In addition to a growing local organization (40% of the people of Chiapas refuse to pay electricity bills), in San Cristóbal in May, representatives of 20 organizations from seven Mexican states formed the National Network of Civil Resistance to the High Prices of Electrical Energy. Rooted in the strength of their organization (“if one is affected, all are affected”), the detention of 5 people resisting against high electricity prices in Candelaria, Campeche at the beginning of July has sparked acts of solidarity and protest in many other parts of the country.

Mines

Another issue which continues to generate mobilization has been that of mining. In the middle of April, around three thousand Catholics from various municipalities in the sierra of Chiapas marched to demand the cancellation of 56 mining exploitation concessions granted to corporations from the United States and Canada.