SIPAZ Activities (From mid-November 2010 to mid-February 2011)

28/02/2011

ANALYSIS: Current Events: Seeking alternatives to increasing militarization

31/08/2011The violence that has overtaken Mexico in recent years, far from ceasing to be news, continues being the question of most concern for the nation. On one hand, the debate continues among the political class as to how to confront such violence; on the other hand these new events have shocked and frightened a society that at moments seemed to have accustomed and resigned itself to the violence that was exacerbated by the so-called “war on drugs” initiated by President Felipe Calderón in 2007. The situation is such that a mass grave was found in April in San Fernando, Tamaulipas that contained 177 victims of narco-trafficking, with the majority being migrants.

The indignation for the behavior and omission of the authorities in these cases is seldom directed at the drug cartels, given that whoever would do so would put him or herself in a state of greater vulnerability and at risk of being the next victim. Javier Sicilia, writer and journalist recognized at the national level, identified this challenge by writing an “Open Letter to politicians and criminals,” following the murder of his son in Cuernavaca, Morelos. Summarized by media as stating “we are fed up with you.” The letter questioned politicians’ lack of capacity for “creating the consensus that the nation needs to find the unity without which this country will have no exit […] because the corruption of the judicial institutions generates complicity with crimes and impunity to commit them” and because the majority of the political class “has only […] an imagination for violence, weapons, insults, and, with this, a profound disregard for education, culture, and the opportunities of honorable and good work.” He questioned the violence of the criminals and its lack of honor, given that “they now do not distinguish. Their violence can no longer be named as such because, like the pain and suffering it provokes, it has no name or meaning.” In the same letter, Sicilia called for a march that was held on 6 April in different cities of the country, with the participation of tens of thousands of people.

On 12 April, a communiqué written by Subcomandante Marcos of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) alluded to these manifestations: “the pain and rage of Javier Sicilia (physically far away but close in ideals for some time) make echoes that reverberate in our mountains. It is to be hoped that his legendary tenacity, as now called for by our word and actions, succeeds in bringing together the rages and pains that are being multiplied in Mexican lands.” At the end of April, the EZLN called on its support-bases, the Other Campaign, and the National Indigenous Congress to join the National March for Justice and against Impunity slated to be carried out at the beginning of May.

Human rights: challenges and tasks

The United Nations Work Group on Forced and Involuntary Disappearances presented a preliminary report at the close of its visit to Mexico in March. It recommended that the armed forces cease working in public-security operations. It recognized that disappearances in the country have occurred in the past “and continue on in the present.” Human-rights organizations claim that the frequency of this crime has increased since the armed forces began participating in the work of public security, and they report 3000 complaints.

In other news, challenges from international platforms multiplied, indicating the deterioration of the context for human-rights defenders in Mexico. 23 organizations from 11 countries represented in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in Washington denounced more than 2000 violations against defenders in the Americas. They described an alarming situation and detailed that the countries with most denunciations are Colombia, Mexico, and Guatemala, in that order. At the European Parliament in Brussels, Mexican human-rights defenders denounced that “the Mexican State pretends to have a legitimate interest before the international community in the attacks and harassment directed against rights-defenders, but daily reality is rather different. Contrarily a continuous situation of risk is experienced.” These defenders spoke to the necessity of having a protection-mechanism for defenders and journalists, with the participation of civil society in its design. This is a task that has met with little progress in spite of the concern expressed publicly by the government on the subject. Finally, at the close of April, the annual report on the situation of human rights in the world published by the U.S. State Department presented fairly negative conclusions regarding Mexico.

Chiapas: denunciations and mobilizations

Considering the national situation, the annunciation of new processes of militarization of the border of Chiapas with Guatemala is surely alarming. Some weeks ago, the anti-drug agency of the United States (the DEA) recommended that the Mexican government militarize the southern border in a manner similar to the case of the northern border. In response, and in a rather unusual manner, Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, commander of the Seventh Military Region, reported that 14000 soldiers are found in the state, and that 40000 had been stationed there following the EZLN’s 1994 insurrection. He added that the threats on the border are derived from groups of organized crime, and he denied the existence of groups of armed civilians—or, at least, he denied that such could be considered dangerous.

The beginning of the year was marked by several communiqués released by the EZLN, following a silence maintained since the end of 2008. In his communiqué of 12 April, Subcomandante Marcos presented a strong criticism of the state government of Juan Sabines, who “persecutes and represses those who do not join his false chorus of praise for his lies-made-government, which persecutes human-rights defenders in the Costa and Altos of Chiapas as well as the indigenous of San Sebastián Bachajón who refuse to prostitute their land, and which encourages the action of paramilitary groups against Zapatista indigenous communities.”

Similarly, at the close of March, the National Network “All Rights for All” at its National Assembly made a public statement on the situation of human rights defenders in the southeast of México. Denouncing that “the generalized violence in the country and the exacerbation caused by impunity worsen the context of repression, poverty, criminalization, migration, territorial looting, and attacks on those who promote, defend, and exercise all rights for all.”

© lavozdelanahuac

Whether a part or not of a strategy of harassment against the Other Campaign (an initiative started by the EZLN in 2005), the harassment directed against organizations of the coast, also adherents to the Other Campaign, in recent weeks has also proven alarming. On two occasions in less than a month, Nathaniel Hernández, director of the Digna Ochoa Center for Human Rights (Tonalá), was arrested. The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC) manifested its “concern for the utilization of legal actions against human-rights defenders toward the end of harassing such persons judicially and of discrediting their work as defenders and promoters of human rights.” Nataniel Hernández was released “with reservations” in the first case and under bail in the second; his legal case continues open to date.

In the case of San Sebastián Bachajón, municipality of Chilón, the CDHFBC published a special report entitled “Government creates and administers conflicts for the territorial control of Chiapas” that describes the confrontation over the control-point at the entrance of the Agua Azul waterfalls, which occurred on 2 February. It denounced the strategy of the state government to generate confrontations so as to have territorial control of regions rich in natural resources. Those of the communally held land of Bachajón (ejidatarios) expressed similarly that the controversy “was financed by the three levels of government, elaborating an agreement with the authorities of the municipality of Tambala and the officials of San Sebastián Bachajón so as to hand over the eco-tourist center to the government.” On 8 April, the participants in the common lands and adherents to the Other Campaign retook the control-point in a non-violent fashion. The following day, an operation in which some 800 federal and state police participated returned to recover it. The ejidatarios decided to flee, stressing that they did not do so voluntarily, as the official version stresses, but rather so as to protect themselves from aggression. Death-threats from official groups in the ejido have been directed against the human-rights defenders and those, who visit in solidarity – particularly internationals.

In general terms, the principal “red alerts” and flags of struggle in the state continue revolving around the problems of “land and territory.” The Regional Forum in Defense of Land, Territory, and Natural Resources, held in March in the municipality of Frontera Comalapa, denounced several types of projects such as “hydroelectric dams, eco-tourist centers, mining projects, monocultures (pine and African palm, among others)” that cause “divisions, confrontations, sickness, environmental pollution, conflicts, death-threats, deaths, [and] criminalization of social protest.”

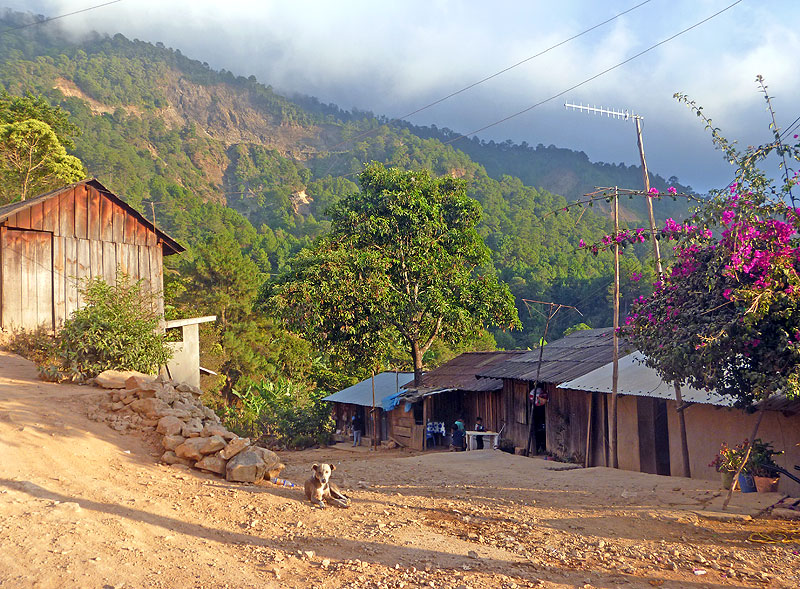

After visiting the state, “Global Justice Ecology Project” published that it had found in Chiapas “projects of economic development imposed on campesino and indigenous communities without any free and informed type of participation in the decision. Among other projects, a governmental program to mark the boundaries of the Protected Natural Areas.” is included. In an act that could represent a precedent, residents of the New Center of Population Montes Azules, municipality of Palenque, carried out a roadblock in March to demand that the promises made by the state government upon their relocation in 2005 be observed. The group, Enlace, Capacitación and Comunicación, stressed that “They were offered a dream but were given a nightmare.”

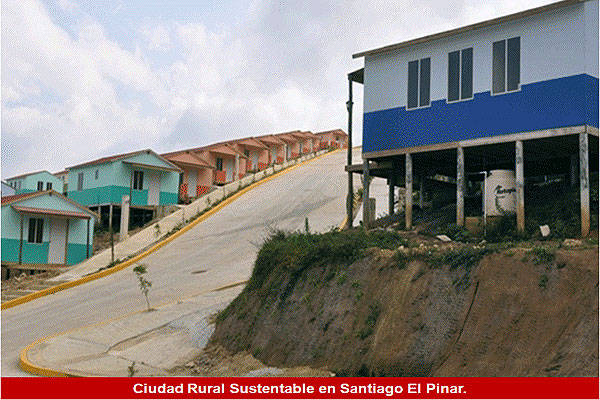

At the end of March, President Felipe Calderón inaugurated a new Rural Sustainable City (CRS) in Santiago El Pinar, one of the projects that the state government has promoted strongly. Although nearly all the media republished the state government’s press-release on the question without changes, it should be remembered that, from the beginning, the project of the CRSs has been criticized strongly by civil society.

With regard to impunity, serious irregularities were denounced in March in the judicial investigation regarding the murder of three indigenous individuals and the forced disappearance of four others during the violent incursion of civilians and 300 police into the community Viejo Velasco, municipality of Ocosingo, in 2006. In other news, another indigenous individual sentenced in the Acteal case (community of the massacre in which 45 people were murdered in 1997) have been released. To date approximately 60 indigenous individuals have been exculpated for these acts, while another 23 remain imprisoned for up to 35 years on the charges of homicide and bearing of arms for the exclusive use of the Army.

Oaxaca: some progress, but much to be done

Among the principal advances in the struggle against impunity was the announcement made by the Secretary of Control and Governmental Transparency in April that financial irregularities amounting to 1.735 billion pesos had been discovered within the final year of the state government of Ulises Ruiz Ortiz. The representative of the Secretariat noted that “we are barely scratching the surface thus far.”

Another advance was seen in the detention in April of one of the presumed material authors of the October 2010 murder of Heriberto Pazos Ortiz, founder of the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle (MULT). Nonetheless, the state attorney general recognized that the presumed contractors of the crime were murdered seven days after the attack, and for this reason more information is lacking as regards the possible intellectual authors of the murder.

Nevertheless, civil-society organizations have indicated several limitations in the struggle against impunity, for example in the case of the so-called Prosecutorial Office for Investigations into Crimes of Social Transcendence, which to date lacks a prosecutor. Civil society has requested that Gabino Cué commit to advancing with the creation of a Commission of Truth that would allow light to be shed on the political crimes of the past.

In other news, on 27 April occurred the one-year anniversary of the murder of Bety Cariño (member of the organization Center of Communal Support Working Together—CACTUS) and of Jyri Jaakkola (a Finnish international observer) as they particiapted in a humanitarian caravan en route to San Juan Copala. If little progress has been achieved in this case – even with the death of an international – little can be expected as regards the death of the other nor of the many murders that have taken place in the Triqui region since that time.

Another challenge for the new government is represented by the exacerbation of tension with the Section 22 of the National Union of Educational Workers (SNTE), with indications that suggest a possible return to the situation of 2006. On 15 February, protestors expressing their rejection of the visit to Oaxaca de Juárez of President Calderón engaged in confrontations with police units. At least 28 people were injured, including teachers, journalists, photographers, and police. The following day, teachers of Section 22 blocked more than 37 roads in the state to protest the repression. They also carried out a number of mobilizations in the subsequent weeks.

Finally, among the more thorny themes there still exist old agrarian problems (the case of Chimalapas) along new bases of tension regarding land and territory. For example, recent protests have been carried out against the planned hydroelectric dam Paso de la Reina and against the San José del Progreso mine exploited by the Cuzcatlán company, with Canadian financing.

Guerrero: new government, old problems

Upon finishing his term in office, governor Zeferino Torreblanca received strong criticism for the bloody legacy of his administration. The Workshop for Communal Development (TADECO) and the Committee of Relatives and Friends of the Kidnapped, Disappeared, and Murdered in Guerrero noted that “[the] government of Zeferino Torreblanca opted for repression as a means of governing […], as is reflected in the existence of more than 250 arrest-orders against social activists and human-rights defenders.” Juan Alarcón Hernández, president of the Commission on Human Rights in the state of Guerrero (CODDEHUM), assured that during the six-year term of Torreblanca, Guerrero suffered regression in terms of human rights. His organization registered at least 202 kidnappings, more than 5000 murders (including that of 11 journalists and 447 women), in addition to 170 disappeared. During the final week of the government of Torreblanca, the installations of the newspaper El Sur de Acapulco were closed due to death-threats directed against its employees. The director of the daily found the governor responsible for these threats.

On 1 April power was taken by the new governor, Ángel Aguirre Rivero, candidate from the “Guerrero Unites Us” alliance comprised by the Party of Democratic Revolution (PRD), Convergencia, and the Labor Party (PT). Days after taking office, Aguirre Rivero met with members of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to La Parota (CECOP) so as to familiarize himself with their arguments against the construction of the hydroelectric dam La Parota near Acapulco. In meeting with CECOP, Aguirre emphasized that he would respect the decision of the comuneros of the zone who would be affected by La Parota. CECOP also celebrated the annulment of the 28 April 2010 assembly that ‘approved‘ the expropriation of 1300 hectares for the construction of the dam, this in the absence of opponents of the project and with the presence of hundreds of soldiers. The Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights noted that “with [the recent resolution] there are five cases that have been resolved in favor of the comuneros and ejidatarios opposed to La Parota.”

That repression against activists continues to be critical in Guerrero was seen in the murder of Javier Torres Cruz, member of the Ecologist Organization of the Sierra de Coyuca and Petatlán and witness against the cacique Rogaciano Alba Álvarez in the case of the murder of the human-rights defender Digna Ochoa y Plácido (2001). After having testified, Torres and his relatives were harassed and received death-threats on various occasions. On 18 April, Javier torres was ambushed and murdered by a group of armed men, presumably following the orders of the aforementioned cacique. Upon learning of the event, two of Torres’ brothers sought out the place of the murder, where they were also fired upon. One of the two was gravely injured. Amnesty International has expressed concern for the life and integrity of the relatives of Torres Cruz and the residents of the community La Morena, where Javier lived.

In more hopeful developments, three members of the communal radio Ñomndaa were released from prison. They had been accused for the crime of kidnapping and had been sentenced to imprisonment for 3 years and 2 months as well as a fine of 1,753 pesos. In any case, according to counsel, no evidence existed for the claim that the accused had participated in the acts.

Another hopeful development is to be found in the regions of La Montaña and Costa Chica, where a campaign in Defense of Land has begun called “With open hearts we defend our Mother Earth against mining.” On 28 March, several organizations, communal free radios, and alternative media met to initiate activities against mining exploitation in the zone. From only 2005 to 2010, some 200,000 hectares of indigenous territory of the region were turned over by the federal government to foreign mining companies, with no regard for the right to consultation of indigenous peoples.