ANALYSIS: Current Events – Of changes and continuities

30/07/20102010

03/01/2011On Oct. 18, president Felipe Calderon proposed a reform to the legal code pertaining to military and legislative justice. Mexican civil society had called for reform many times, but it appeared to be the recent condemnation by The Inter-American Court of Human Rights that brought about this action. The reform would change military law so that torture, forced disappearances and sexual assaults would be tried in civil courts. Up until now, military tribunals have had the power to punish members of the Armed Forces who had violated human rights. This reform is an attempt for the federal executive to comply with punishment dictated by The Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the case of the forced disappearance of Rosendo Radilla during the so-called “Dirty War” and of the rapes of two meph’aa indigenous women, Ines Fernandez y Valentina Rosendo. These human rights violations occurred in 2002 and were committed by members of the Mexican army in Guerrero.

International human rights organizations criticized the proposed reform as inadequate. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Mexico declared the initiative fell short because it didn’t address all the violations committed by the military against civil society. Following in the same vein, the United Nations special envoy for the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul, criticized the reform for failing to include violations that were equally serious such as extrajudicial execution.

Various national human rights organizations protested in a joint press release, saying the reform maintains conditions that favour impunity. They explained the reform would fail to harmonize internal legislation with international treaties on the subject. On top of that, the organizations pointed out sentences imposed by The Inter-American Court of Human Rights would not be respected under this new ruling since the reform of article 57 of the military justice code takes into consideration the fact that military law isn’t competent to judge, under any circumstance, any violations committed by members of the armed forces when they involve civilians.

The violence continues

During the last few months, federal police have captured high-level drug traffickers, most notably Edgar Valdez Villarreal (La Barbie). Villarreal’s arrest occurred on Aug. 30, two days before the president’s report. The timing raised suspicions that a pact may have been made in light of the constant demands of various sectors of civil society regarding human rights violations and deaths caused by the government’s strategy against organized crime. Calderon’s government took advantage of the high-profile detentions to justify the deployment of troops to fight organized crime. But despite the arrests of various leaders, or capos, the level of violence has shown no signs of decreasing and there are no indications the violence will decrease over the short or long-term.

Attacks that can be categorized as massacres have been documented in recent months, most notably the murder of 72 Central and South American migrants in San Fernando, Tamaulipas at the end of August. Apart from showing the cruelty of the criminal gang responsible, it also highlights the lack of protection for migrants. It’s important to note that the lack of protection for migrants exists not only in the north, but also throughout the country along routes used by migrants. Testimonials by staff at shelters speak of frequent kidnappings and extortion.

The violence that has already claimed around 30,000 lives during Felipe Calderon’s presidency, and the attacks by organized crime and state force have caused innocent people to die from different levels of society. Another phenomenon that has increased since the military have been fighting organized crime is forced disappearances. The Latin American Association of Family members of Detained/Disappeared estimates that under Calderon, about 3,000 disappearances have occurred. Out of these, 400 are politically motivated, 500 are because of human trafficking. 2,100 are because of organized crime and often occur with no obvious reason. Organizations dedicated to searching for the disappeared say that many cases may have been committed by agents of the State, since testimonies say the perpetrators wore uniforms.

Social and human rights activists in the north have begun to talk about “social cleansing” as a hidden motive in the “war against drugs”. This theory is based in the fact that number of dead and disappeared has increased since the start of the current federal government’s anti-crime initiatives. In many cases the victims have been youth who belong to gangs. There is no proof to support this hypothesis – mostly because in the majority of cases the homicides go without being investigated, or higher levels of corruption limit the possibility of solving the crime. As a result of these suspicions, various members of the country’s Senate requested information from the National Security and Investigation Centre in September. They wanted to know about the possible existence of so-called “death squads” – armed groups hired to kill those who break the law.

Self-censorship on the part of the media is common because of the danger of reporting and investigating the violence in Mexico, and the lack of protection given to reporters by the authorities. The situation for journalists has gotten worse recently. They’ve become targets for cartels and their offices have been attacked, mainly in the northern part of the country. The cartels have begun to demand the media diffuse their messages. It was within this context that the newspaper El Diario (based in Juarez) published an editorial entitled “What do you want from us?” in September and asked “Members of the different organizations that are fighting over Juarez… You are the de facto leaders of the city because the legal authorities haven’t been able to do anything to prevent our colleagues from being killed despite the fact that we pleaded with them to protect us… We don’t want anymore dead. We don’t want anymore injured, or any more intimidations. It’s impossible for us to do our jobs under these conditions. Tell us; please what you want from us… The State has been absent in its role as protector of citizens’ rights, as well as reporters, during these years of war-like years. Their various operatives have been failures.” Human rights defenders denounced the protection mechanism initiated by the federal government in November as “weak and ineffective” in response to the attacks, murder, extortion and kidnapping facing the profession of journalism in Mexico.

Within this context the Subcomission of Human Rights in the European parliament expressed their worry about national security in Mexico. The commission’s president, Heidi Hautala said, “It’s probably time for Mexico to adopt a different strategy against drugs” – an opinion shared by many analysts in Mexico.

On the other hand, for the first time in the history of financial aid from the United States for Mexico, the U.S. decided to freeze $26 million in aid until advances are made in the area of human rights. The Mexican Senate rejected the stipulation by the U.S. In a meeting with the Secretary of Defence, the Senators asked that this stipulation be rejected saying the amount of financial aid was very little and gave the U.S. the power to influence internal decisions. It’s important to note the $26 million represents only 15 per cent of the total aid being given to Mexico by the U.S.

Some hope in Guerrero

© SIPAZ

Despite facing a context of abuse and human rights violations, some social activists have experienced victories in the state of Guerrero. Among them are the cases of Ines Fernandez and Valentina Rosendo, members of the Organization of Indigenous People Me’phaa (OPIM). These two women won their case against the state for sexual assault at the hands of the military in 2002. In addition, Raul Hernandez Abundio was released from jail on August 27 after being jailed unjustly for two years and four months. Hernandez Abundio had been accused of murdering Alejandro Feliciano Garcia in January 2008. Amnesty International pronounced in favour of compensation for the time Hernandez Abundio spent in jail.

But the harassment and threats haven’t stopped. On August 28 two unidentified people threatened and tried to kidnap the daughter of Ines Fernandez in the main town of Ayutla de los Libres. During the attempted kidnapping, the perpetrators made reference to Raul Hernandez which is why Hernandez decided to stop all public appearances. On August 30, a coordinator from the Organization for the Future of the Mixteco People (OFPM), Alvaro Ramirez Concepcion, was attacked with weapons and hospitalized as a result.

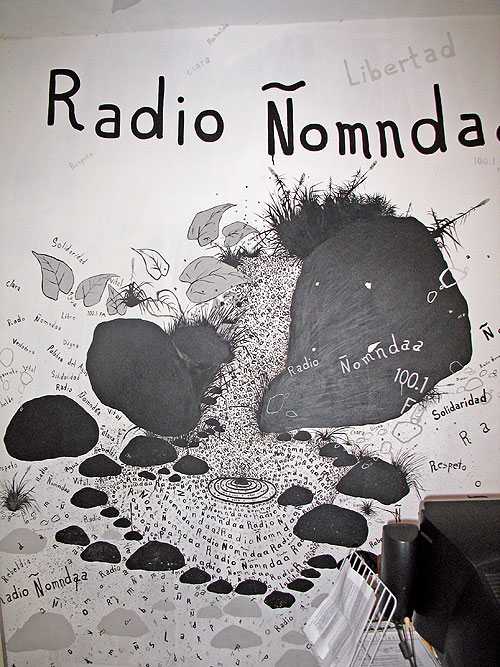

On Sept. 27, Genaro Cruz Apostol, Silverio Matia Dominguez and David Valtierra Arango were sentenced to three years and two months in prison. The three men were members of the community radio station “Radio Nomndaa” (The word of the water) and were jailed for allegedly holding Narcico Garcia Valtierra – someone close to the ex mayor Aceadeth Rocha Ramírez — against his will. The Montana Tlachinollan human rights centre said the sentence showed the corruption and lack of impartiality in the justice system, and the fact that the justice system criminalizes social protest and grants impunity to those who commit crimes from positions of power. The sentence will be appealed.

In October 2010, the regional coordinator of Community Authorities and Community Police (CRAC-PC) celebrated their 15th anniversary. The autonomous self-management model of justice was born out of the high level of crime at the time in the Montana y Costa Chico de Guerrero region. The final declaration of the assembly stated the mechanism of security and justice in the state are totally incapable of bringing safety and justice to the people. Its purpose has been to decimate and reprimand the communities and social organizations who have decided, with dignity, to raise their voices to denounce the abuses and insults from the government and the capitalist system.

A wave of assassinations at the end of Ulises Ruiz’s reign in Oaxaca

In the months between the state elections in July and the new governor’s entry into office at the beginning of December, there has been an increase in violence and political murders. On Oct. 22 Catarino Torres Peresa was killed in Tuxtepec. Torres Peresa was a member of the Citizens’ Defence Committee (Codeci) and was one of the first political prisoners of the Popular Assembly for the People of Oaxaca in 2006. The next day, in the capital of Oaxaca, the leader of the Unification and Triqui Fight Movement (MULT), Heriberto Pazoz Ortiz, was shot and killed. Pazoz Ortiz was the founder of the United Popular Party – considered the only indigenous political party in the American continent. The leaders of MULT condemned the murder and said it was committed from people in positions of power. The governor-elect, Gabino Cue Monteagudo said the murder would not go unpunished. Cue Monteagudo will take office at the beginning of December.

The assassination of the leader of MULT was one more aggresion in a series of violence that has affected the Triqui people recently. The Unification Movement and the Triqui Fight Independent (MULT-I), an organization linked to the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala, has denounced the murder of four people in September and October. In response to a rumour about a possible massacre, 100 families who support the Movement abandoned San Juan Copola in September. On Oct. 7, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights granted protection to 135 residents. But despite their involvement, the violence continues and the state government has continued showing itself to be unresponsive to the conflict the Triqui people face.

Oaxaca as well as Chiapas were very affected by the tropical storm “Matthew” at the end of September. In both states, intense rain caused landslides as well as the deaths of dozens of people. The loss of crops has also been reported as a result of the storm, which will affect populations that are among the poorest in Mexico (according to statistics) and who rely on these crops for their own consumption.

Chiapas: The harassment and threats continue

© Comité Hermanas González

After more than 16 years since the rapes of indigenous tseltals Ana, Beatriz and Celia Gonzalez Perez in Altamirano by the military, the women have accepted compensation from the Chiapas government. But in an open letter, the women wrote they accept the proposal “as the only proof that the Mexican government publicly acknowledges the violation of out bodies, our rights and our dignity. Of course we alsowant them to recognize the hurt they have caused our mother.” They added, “We do not accept to be present at any public appearance for the government so that the government can use our words in their favour. We don’t accept the programs they offer either, because they don’t fix the problems of the people. We’re already organized in our town to fix our problems… We demand and will always demand that the military that hurt us be punished… We also demand the military leave out towns because they continue to rape, they bring prostitution and they terrorize and hurt the people.” Their case was presented by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1996, and was accepted in 1998. But the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights only made one recommendation given that Mexico had accepted the jurisdiction of the Inter-American system in 1998, two years after the complaint was presented.

In the case of the Acteal massacre of 1997, last October 15 people were released from jail after serving time for having participated in the massacre. The civil group The Abejas demonstrated their indignation for the mass release. The Fray Bartolome Human Rights Centre (Frayba) said the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights was studying the Acteal case. It’s worth noting that 34 people were released from jail in 2009 despite having been charged with participating in the massacre because the proper justice process had not been followed. The release of prisoners has caused members of the Abejas worry and anxiety, as they fear for their safety if the newly freed prisoners return to their hometown.

© Common Frontiers de Canadá

As well, natural resources in Chiapas are being threatened by two projects. Various groups are fighting against a mining project in Chicomuselo started by a Canadian mining company called Blackfire. In November 2009, one of the leaders of the anti-mining movement, Mariano Abarca Roblero, was killed. The mining project is suspended for the moment, though not necessarily for the long term. The priest of Chicomuselo, Father Eleazar Juarez Flores, has also received death threats for accompanying the processes of local organizations that opposed the mining activities and were working to defend their land and environment.

On Sept. 9, 2010, 170 Bases de Apoyo Zapatistas (BAZ) were forced to abandon their community, San Marcos Aviles in the municipality of Chilon, because a faction of the community opposed the construction of an autonomous school and were threatening the members of BAZ. After more than one month of forced displacement, the Zapatistas dispite the risk involved decided to return to their homes. According to a complaint made to the Junta of Good Government in Oventik their homes had been “looted and some semi-destroyed, but also proclaimed “our base of support remains because we have the right to live on our land and to work the land.”

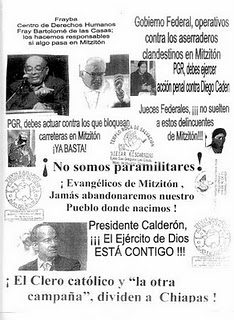

Civil organizations have also been targets of harassment recently. On Oct. 5, the Fray Bartolome Human Rights Centre (Frayba) said that during a demonstration a few days earlier by the evangelical group “Army of God”, pamphlets that were defamatory to some of Frayba’s workers were handed out. Before the demonstration, the Army of God’s leader, Esdras Alonso Gonzalez, wrote a letter to the Secretary of Government stating “the conflicts that have been developing in the highlands region are a result of the presence of activists and international organizations and the participation of foreigners in the social network belonging to the Fray Bartolome Human Rights Centre.”

On Oct. 14, the Indigenous Training Centre CIDECI-Unitierra denounced the harassment on the part of presumed employees of the Federal Electricity Commission. Its worth mentioning that the Indigenous Training Centre has had a generator for the past four years and as a result doesn’t need the services of the Federal Electricity Commission.

As part of the Chiapas government’s agenda in the area of human rights, the Executive has made a proposal to the Chiapas government that would shut down the present State Commission for Human Rights to create a State Council on Human Rights, with five councillors designated from different areas of civil society, including academia, non-governmental organizations, and human rights organizations. It is well that the new structure includes greater participation from civil society, but it remains to be seen whether it will be better able to confront the serious violations to human rights that still happen in Chiapas, and lately, more than ever against social movements.