SIPAZ Activities (December 2002 – February 2003)

30/04/2003

UPDATE: Chiapas, ten years after the armed uprising

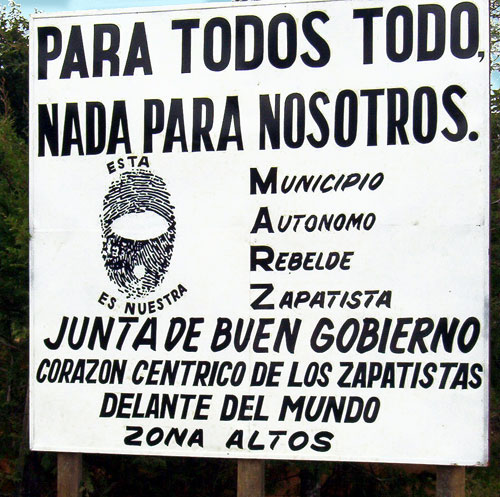

26/12/2003ANALYSIS: Resistance and autonomy, the creation of the zapatista juntas of good government

Last July, the Zapatista Army for National Liberation (EZLN) reclaimed the initiative with a series of communiqués, which announced the end of the Aguascalientes (meeting spaces for the EZLN and civil society, located in the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities) and the creation of the Juntas of Good Government, all of which amounted to a surprising political repositioning (see www.ezln.org.mx). The Zapatistas continue to create autonomy by acting through and strengthening the civil resistance process, a process that has been maturing for many years.

One More Step Toward Creating Autonomy

In July, Subcomandante Marcos (the designated spokesperson for the Zapatista command) stated that, due to the lack of responses from various levels of power in regard to the indigenous demand for autonomy, the San Andres Accords “will simply be applied in rebel territory”. In addition, he announced that Zapatista municipalities “have prepared a series of changes, which have to do with their internal functioning and their relationships with national and international civil society”.

Subsequently, after critically analyzing the difficulties that they face, the EZLN announced the death of the “Aguascalientes“. In their place, they have installed “Caracoles, Houses of the Juntas of Good Government”: “(. . .) they will serve as doors of entry into and exit from communities; as windows so we can see into ourselves and so that we may see the outside; as horns that will broadcast our word far and wide and will allow us to hear other words from afar.”

Each of the five Juntas of Good Government will consist of one or two delegates from each of the Autonomous Councils in each zone, thus embracing the 30 Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Rebellion.

The Juntas of Good Government will perform the following functions, among others:

- “Attempt to counteract the inequality of development between autonomous municipalities and communities.

- Mediate conflicts presented to autonomous municipalities and conflicts between autonomous municipalities and official municipalities.

- Attend to denunciations against the Autonomous Councils for human rights violations, protests, and inconsistencies, investigate their veracity, and order the Autonomous Councils to correct errors and monitor changes.

- Monitor projects and community works in the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Rebellion, ensuring that projects and works are completed in the timeframe and manner agreed to by the communities; and promote support for community projects in Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Rebellion.

- Monitor the implementation of laws that, having been agreed to by the communities, function within the jurisdiction of the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Rebellion.

- Attend to and guide national and international civil society members who visit commu-nities, support productive projects, install human rights observation camps, carry out research (note: research should benefit communities), and participate in any other activity approved by communities in rebellion.

- In accord with the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee–General Command (CCRI-CG) of the EZLN, promote and approve the participation of members of the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Rebellion in activities or events outside of the communities in rebellion, and select and prepare these members for said activities and events.

- Care for Zapatista territory in rebellion that it manages, which it manages by obeying.”

The EZLN invited civil society to the death of the Aguascalientes and the inauguration of the Caracoles at the “Caracol” of Oventik (in the Highlands of Chiapas) from the 8th to the 10th of August. Ten zapatista comandantes, 100 representatives of autonomous municipalities, thousands of zapatistas and members of national and international society attended the event.

The new structure strengthens the EZLN from within and without, from top to bottom, clearly establishing channels for communication with national and international civil society: “So that the civil society now knows with whom it must confer for projects, human rights observation camps, visits, donations, etc. Human rights defenders now know to whom they must turn in relation to denunciations that they receive and from whom they should await responses. The army and the police now know who to attack (taking into account that the EZLN will also be there). The media that says ‘those who pay us speak,’ now know whom to slander and/or ignore. The honest media now know where to go to solicit interviews or reports in communities. The federal government and its “commissioner” now know what they have to do to stop existing. And Power and Money now know who else they should fear” (The Thirteenth Stele, Part Six).

Proposals, From Local to International

In the fifth communiqué from July, Marcos raised a sensitive topic: the delicate relationships between zapatista communities and non-zapatista communities. The EZLN has aimed to strengthen the operation of communities where power is distributed democratically, horizontally, and on a rotating basis. Yet it has recognized that, in cases of conflict or differences, the final word has rested with the EZLN: “The military structure of the EZLN in a way “contaminated” democratic traditions and self-government. The EZLN therefore constituted an “antidemocratic” element within a communal system of direct democracy.”

At Oventik, the EZLN announced the end of checkpoints and tolls on highways and roads within its control as a gesture of good will toward non-zapatista communities. It also defined a new relationship between the autonomous municipalities and the military arm of the Zapatistas: the “shadow” of the EZLN will step back and allow the communities to take the lead. Now more than ever, the zapatista experiment appears as one of resistance rather than military force, adopting a proactive attitude in terms of civil disobedience, each time assuming more explicitly the functions of government.

Nevertheless, the EZLN will continue defending the autonomous municipalities. In this vein, it sent strong messages to paramilitary groups, “especially those in the Highlands zone of Chiapas.”

On an international level, in relation to Plan Puebla Panama (PPP) , “the Zapatistas have the means and the organization to stop steps being taken to put into effect this plan.” As counterproposals, the EZLN has proposed Plan La Realidad-Tijuana; for the north of the American continent, Plan Morelia-North Pole; for Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, Plan La Garrucha-Tierra del Fuego; for Europe and Africa, Plan Oventik-Moscow, reaching toward the east; for Asia and Oceania, Plan Roberto-Barrios New Delhi reaching toward the west. The EZLN also announced that it would participate in the mobilizations against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Cancun during September. It had been a long time since the EZLN announced its social agenda against economic globalization with such clarity and definition.

The words of the EZLN arrived at the summit in Cancun through the organization “Via Campesina,” which brought a recording of comandante Esther, comandante David, and Subcomandante Marcos. They motivated civil socierty to continue resisting in the struggle against neoliberalism and to construct, through autonomy, a world where life triumphs over war.

Reactions

Members of the federal government took a variety of positions in response to the Zapatista repositioning. For Xóchitl Gálvez, head of the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Villages, the indigenous problem that persists in Chiapas has “only one real solution: to advance in constitutional reform, as the last changes have left both communities and zapatistas dissatisfied.” She celebrated the fact that the new proposals were more political than martial in character, an aspect celebrated by the State Department as well.

On September 1, President Fox presented his third report to the government, dedicating a large portion of his speech to structural reforms within the agricultural, labor, telecommunications and energy sectors. In regard to the situation of indigenous villages, he emphasized the creation of the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Villages. Said Commission was rejected by more than 50 indigenous organizations and human rights defenders because they were not consulted before its creation.

Official government speech has tried to frame the Juntas of Good Government within the Constitution which, thanks to the last constitutional reform, allows for indigenous autonomy. We must remember that this very reform was rejected by the EZLN for not respecting what had been established in the reform law known as COCOPA. The COCOPA law took into account the most important agreements from the San Andres Accords. For the EZLN the Juntas of Good Government represent one more step on the path of resistance, meanwhile the government is trying to define them within a constitutional framework so they appear to be government-backed reform.

At the state level, PRI and PAN representatives from Chiapas’s Congress rejected the creation of the Juntas of Good Government, claiming that they violate the state’s rights and that they will further polarize the social fabric.

On the other hand, Chiapas’s government commissioner for reconciliation of communities in conflict, Juan González Esponda, affirmed that Pablo Salazar’s administration believes that “no form of government that seeks to improve the situation of the indigenous violates the law.” He characterized the initiative as “an interesting effort by communities to search for new solutions to their conflicts.”

Representatives of the National Indigenous Congress (which brings together a large part of the indigenous movement in Mexico) committed to continue following the Zapatista example, promoting indigenous autonomy throughout the country and defending the rights of the indigenous people. Representatives from a variety of campesino organizations celebrated the birth of the Juntas of Good Government, affirming that the Juntas represent an extraordinary instrument for exercising popular democracy.

Legislative Elections: Abstention, The Only Winner

The repositioning of the EZLN was all the more relevant within the post-election environment in which it arose. On July 6, Mexico held federal elections for members of Congress, and there occurred the largest rate of abstention in the country’s recent history, with a record 58.32% of voters (more than 37 million abstaining). Although the electoral census counted 15 million more voters, fewer cast their votes this time around than in the interim elections during 1997 and 1994. Beginning in 1988, civil society mobilized, demanding respect for each vote and clean elections. Today, however, it appears that disenchantment prevails: the large percentage of abstentions is read as political punishment, not only of the Fox government but also of the dominant political parties, reflecting society’s disappointment with alternative policies and the lack of real options.

In the last elections, none of the political parties obtained above 35% of the vote. Nevertheless, the final results point to an apparent reconsolidation of power for the Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI), after its defeat in the presidential elections of 2000. The PRI obtained 36.9% of the vote and a total of 224 representative seats, which means it now has the highest percentage of the seats in the Congress among the different political parties, though the party is still far from its heyday when it represented more than 50% of congressional votes.

The National Action Party (PAN, President Fox’s party) was this election’s big loser, as it did not obtain the majority necessary to pass proposed reforms without negotiating with the opposition. Nevertheless, the PAN won 32.83% of the vote (which translates into 153 representative seats), corresponding to the voting percentages it has won in the past, barely three points below the PRI.

The Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD, the center-left opposition party) consolidated its position in Mexico City, where it won in a landslide, due to the popularity of PRD member Manuel Lópex Obrador, governor of Mexico City. Obtaining a total of 18.77% of the vote (95 representative seats), the PRD maintains itself as Mexico’s third political force, but it did lose presence outside of Mexico City.

The other three parties that will be represented in the next Congress are the Green Ecology Party of Mexico (PVEM) with 6.55% of the vote (17 representative seats), the Labor Party (PT) with 2.55% (6 representative seats), and Convergence with 2.41% (5 representative seats). The rest of the parties that were up for election did not obtain enough votes to win seats in Congress.

With these results, even if it is true that Mexico has reached a level of credibility in regard to its electoral processes, it is concerning the lack of legitimacy the next House of Representatives will have. The largest minority is the PRI, representing around 15% of the electorate identified by the census. On the other hand, the significant fragmentation of the House of Representatives will make it difficult to reach consensus on any reforms.

Conflict in the Montes Azules Biosphere: A Preeminent Red Light

After much tension generated by months of threats and displacements (see www.sipaz.org), the government of the state of Chiapas and Lacandón authorities agreed to a truce, which will put a halt to the displacement of communities in the Montes Azules Reserve. Government authorities will undertake to guarantee diverse economic supports for the ethnic inhabitants of the Reserve, while the Lacandones will stop their attempts to expel other indigenous groups from the region.

In May, the relocation of 28 indigenous Chols, who voluntarily abandoned the Montes Azules Reserve in December, was postponed for the fifth time. The Federal Prosecutor for Environmental Protection (PROFEPA) had promised to give the Chols new lands. The Choles broke dialogue with the government and decided to move themselves to the municipality Marqués de Comillas at their own expense.

Mario Hernández Pérez, from the Coalition of Autonomous Organizations in the State of Chiapas (COAECH) stressed that, “this shows that the federal government has neither the will nor the resources to resituate the communities currently located in Montes Azules.” He added that, “now more than ever, the position of the indigenous people living in Montes Azules is that they will not accept relocation, because the government does not live up to its word.”

Human Rights Latecomers

Although there have been advances in regard to Mexico’s human rights situation, the Interamerican Commission of Human Rights (CIDH), in a report released in April, expressed concern at the steady deterioration of institutionalized democracy. In 2002, Mexico occupied second place in denunciations presented to the CIDH and sixth place in requests sent by the CIDH to the government asking it to implement measures of security for the purpose of offering protection to people who made denunciations when their fundamental rights were violated.

The Mexican Office of the High Commission for Human Rights is initiating an analysis of the human rights situation. The end goal is to obtain precise information about human, individual, civil, and political rights obstruction so as to comply with international agreements.

Almost a year and nine months after the death of lawyer Digna Ochoa y Plácido, the special commission created to investigate the case closed the investigation affirming that the human rights lawyer killed herself. After family members decided to challenge the decision and national and international organizations rejected it, attorney Bernardo Bátiz said that he would give the go ahead to departments of internal and external revision.

Processes of Resistance at a Regional Level

In June, the President of the Central American Parliament, Augusto Vela, recognized three pending issues within PPP: project financing, more consultations and meetings with involved populations, and, above all, social development.

Mexico, much like the rest of Central America, has seen an increase in the coordination of meeting spaces for those opposed to the economic mega-projects. Here, we highlight a few among many of such meetings.

The Continental and Global Meeting against the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) and the WTO took place in Mexico on May 11 and 12. Delegates from more than 150 international organizations agreed to a world agenda for mobilizations, actions of resistance and civil disobedience against FTAA promotion, the WTO meeting in Cancun, and to “unmask” the fourth summit of the Presidents of the Americas, which will also take place in Mexico at the end of this year.

The National Meeting in Response and Resistance to Neoliberal Globalization in Mesoamerica took place in May in Oaxaca, where around 400 representatives from 130 social and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) united themselves under the slogan “For a future without PPP and without the FTAA!” As the event concluded, attendees underlined the importance of indigenous, campesinos, the marginalized, and excluded creating their own social projects.

The Workdays of Resistance 2003, which took place in Honduras in mid-July, consisted of a series of forums and meetings aimed at strengthening popular struggles in Mesoamerica and the Caribbean and looking for alternatives to economic mega-projects. These forums included The Third Week of Cultural and Biological Biodiversity*, The Second Mesoamerican Forum Against Dams, and The Fourth Mesoamerican Forum Against PPP.

During these forums, attendees planned mobilizations against the Fifth Minsterial Summit of the WTO, which took place September 10-14 in Cancun. Numerous campesino, indigenous, and social organizations as well as Mexican and international non-governmental organizations worked together to provide alternative forums to the summit, in addition to protesting the trade laws established by the WTO’s participating governments. During the week of the WTO summit, there were mobilizations in many countries and states in memory of all of the victims of economic and military wars generated by WTO policies.