ANALYSIS: Chiapas – Carrot and Stick?

26/02/2010

ANALYSIS: Current Events – Of changes and continuities

30/07/2010For decades, Mexico has enjoyed having a favorable international image with regard to human rights. Such an image has less to do with domestic realities and more to do with the mediating role Mexico had played in the armed conflicts in Central America of the 1980s, as well as their strong diplomatic efforts in different international and multilateral institutions. Beyond this, several countries came to think that the fall of the PRI from power in 2000 (the PRI being the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which held the presidency of the country for more than 70 years) marked the beginnings of a “democratic transition” during which a certain margin would be afforded the new governments to affect changes. But at the same time, a number of other countries share Mexico’s understanding of “security,” especially since the declaration of war by the government of Felipe Calderón against drug trafficking and organized crime in 2006.

In Mexico, human rights violations seem to be increasingly considered to constitute “collateral damage” that inevitably occur while efforts are made to realize “the common good.” In this sense, the following declaration, made by the Secretary of National Defense during a mid-April speech before the Congress in which he attempted to justify the presence of the military in the streets of Mexico for the next 10 years, is particularly illustrative: “Despite the deaths of civilians—children, youth, students, and adults—in conflicts between the armed forces and organized crime, the strategy will be maintained; this is collateral damage that is lamentable.”

According to official statistics, violence associated with organized crime has left more than 22,700 dead since December 2006. It should be stressed that murder is only one of the many types of human-rights violations the prevalence of which has exploded with the increasing militarization of the country. Journalistic sources assert that complaints regarding abuse of civilians at the hands of the military have increased more than 400 percent during the current six-year presidential term; the number of such complaints reached 1,644 in 2009. During the first trimester of this year, the Secretary for National Defense had already received 389 complaints—a total greater than that reported each year between 2000 and 2007. In spite of this, only 40 soldiers face imprisonment for abuse, and another 55 find themselves subject to 37 inquiries regarding human-rights violations.

International challenge on various fronts

In recent months, the Mexican State has been strongly challenged on human rights by NGOs (non-governmental organizations) as well as country-governments and multilateral organizations such as the OAS (Organization of American States), the UN (United Nations), the US, and the European Parliament.

On 8-9 March in New York, a session was held of the UN Human Rights Council during which the Mexican government was questioned regarding the implementation of the International Agreement on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by Mexico in 1981, on such issues as militarization, military tribunals, detention, past crimes, the disappearance of the Special Prosecution Office for Past Social and Political Movements (FEMOSSP), torture, prison conditions, lack of clarity on the hierarchy of international agreements above Mexican law, violence against women, the situation of the rights of indigenous communities, and the application of the Constitution’s Article 33 (which has to do with the possibility of expelling foreigners if they are considered to be involving themselves with Mexican political affairs).

On the other hand, on 11 March, the US State Department, allied with Mexico through the “war on drugs,” published the document Reports by country on human rights, 2009. The section on Mexico states that the government respects rights in general, but it also details an immense number of cases of arbitrary executions prosecuted by security forces as well as cases of physical abuse, bad prison conditions, arbitrary arrest, impunity in the judicial system, confessions acquired by means of torture, attacks on journalists, as well as forced disappearances on the part of the military.

On the same day, the plenary of the European Parliament in Strasbourg adopted a resolution entitled “Escalation of violence in Mexico” that expressed its concern regarding the levels of violence seen in Mexico and the climate of impunity that exists in the country, in addition to the attacks on human-rights defenders, journalists, and women. On 12 May, the Mexican government and the European Union arranged a meeting dedicated to a deepening of dialogue and cooperation on human rights. The principal concerns expressed by the EU had to do with impunity and the use of excessive force. It nonetheless recognized the efforts made by the Mexican government to guarantee the respect for human rights in the country.

Finally, the OAS has for several months now come to question the human-rights situation in Mexico through the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court on Human Rights with regard to such cases as that of the Guerrero social activist Rosendo Radilla Pacheco (forced disappearance in 1974 during the “Dirty War.” (See SIPAZ Report – March 2010).

Increasing vulnerability of human rights defenders

On 17 April, the final communiqué of the Third National Encounter of Human Rights Defenders held in Mexico City confirmed tendencies that SIPAZ has been pointing out regarding the increasing vulnerability in which human rights defenders find themselves.

The participants denounced that “due to the work in promotion and defense of human rights” in which they engage, they find that they are “constantly under threat” due to “death-threats, torture, intimidation, illegal privation of liberty, harassment, and even murder.” They affirmed that “adequate mechanisms of protection for our labor” do not exist in Mexico, and they claim that many human rights defenders have had to flee their homes and places of origin due to having received death-threats. Militarization, moreover, “has aggravated the vulnerable situation in which we find ourselves.” They also concluded that this violent context particularly affects women, the indigenous, and journalists.

In this context, the Senate on 8 April adopted a constitutional reform regarding human rights that was passed on to the House of Deputies. According to several human-rights organizations, both national and international, this reform would include such positive measures as the importance of international law, a clear definition of how and under which circumstances a state of emergency can be declared, the right granted to the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH) to investigate violations, and guarantees against the arbitrary expulsion of foreigners. This reform has not yet been adopted, leaving human-rights defenders highly unprotected.

Attack on observation mission in Oaxaca, an extreme example of such vulnerability

On 27 April, a human rights observation caravan was attacked in the community La Sabana, presumably by members of the organization Union for the Social Welfare of the Triqui Region (UBISORT). The caravan had been in route to the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copalá. It mission was to bring humanitarian aid to the residents of San Juan Copalá and document the situation there, given that, as has been denounced, the community has for several months been encircled by UBISORT. This attack constitutes an extreme example of the “situation of vulnerability of those who work in defense and promotion of human rights amidst ever-increasing political violence, criminalization of human-rights work, and governmental disregard of the protection of life and physical security” during the time covered by the report (Communiqué of the Peace Network, 28 April).

The attack resulted in the deaths of Beatriz Alberta Cariño Trujillo, director of the Center for Community Support Working Together (CACTUS), and the international Finnish observer Jyri Jaakkola. The attack left a number of injured, and four were reported disappeared after they resorted to hiding in the mountains for two days. Given the impact that the aggression has had together with the national and international condemnation that followed it, the Federal Attorney General’s Office (PGR) has decided to take on the investigation regarding the events.

Certainly, the region of the indigenous Triqui group has for years suffered a high level of violence within the context of disputes for political, social, and economic control of the region. This situation, claim Oaxacan organizations, has not been addressed meaningfully by the state authorities. It should be mentioned moreover that the attack took place just before the beginning of the electoral campaigns at the state level, developments that have in the past seen a deepening of socio-political conflict.

The Governor of the state of Oaxaca, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz (PRI), denied all responsibility on the part of the state government for the attack. Furthermore, he challenged the participation of foreigners in the caravan, warning that their migratory status should be investigated. With this in mind, the Peace Network denounced in its communiqué that “the Oaxacan government is calling into question international observation, a peaceful mechanism of civil intervention that has proven to be key in putting an end to violence in several different places and contexts.”

Vulnerability exacerbated by the role of the media: more controversy regarding the EZLN in Mexican media

Another tendency that SIPAZ has been pointing out in recent months is the role being played by mass media in the ongoing criminalization of social protest and of the work of human rights defenders: distorting accounts and events, introducing religious interpretations of occurrences, and underplaying other social forces, among other things. The most telling example of this that took place during the time covered by this report was on 27 March, when the daily newspaper Reforma published an article in which a putative ex-member of the EZLN “revealed” that there exists a supposed relationship between the EZLN and the separatist Basque organization ETA. In an unsigned article, the newspaper claimed to have received “a lengthy document” of 83 pages that reportedly details the structure of the EZLN, its finances and armaments, and the international support it receives. More than 100 media outlets, taking the source of the assertions as genuine, ran the following as their headlines: “The investigation of a link between the EZLN and ETA is demanded.”

On April 1, the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights shared the clarification and reply of Leuccio Rizzo, whose face was shown as being that of Subcomandante Marcos on Reforma’s front-page. The Center stressed that “we are concerned that the daily newspaper Reforma […] would offer to publish information lacking in substance that violates the stipulations of the American Convention on Human Rights in articles 11 and 14 which serves as a counter-insurgency measure of the Mexican state to identify and criminalize human-rights defenders.”

Much could be said regarding this journalistic polemic, calling into doubt its content as well as the intentions that lay behind its publication. The federal representative from the PRD José Narro Céspedes, coordinator of the COCOPA (Commission for Agreement and Pacification) emphasized that “To begin with, the granting of eight columns on the front-page and a page in its entirety based on lies, falsehoods, and information of dubious origin speaks to conscious political intentions, or to a pretext for some sort of repressive action.”

The academic and specialist in indigenous law Magda Gomez stressed the following in an article published in La Jornada on 31 March: “What do we suppose is behind the attempt to link Zapatismo with an organization like ETA? Why is the public denunciation omitted that Subcomandante Marcos made of all forms of terrorism, come from wherever it may, in a conflictive interchange of letters with ETA? This is no minor matter, given that it is reminiscent of 9 February 1995, only that this time we don’t know if the attack will be only from the media, or if it is an announced preview of major actions taken by the State—an eventuality we cannot rule out.”

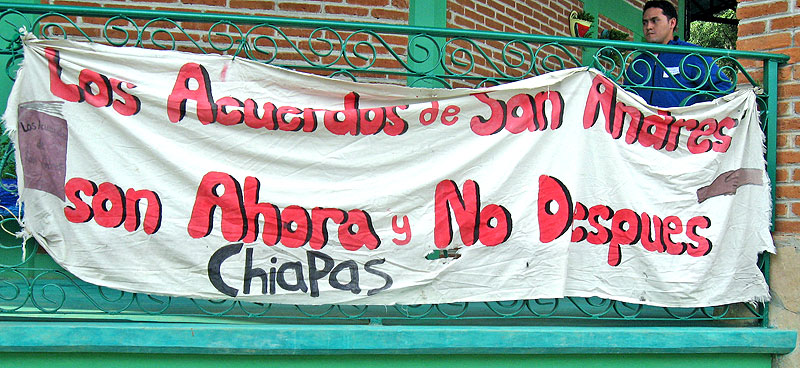

On 22 April, in a forum that took place in the Congress that could seem to be out of place if it were not for the purpose of preventing a return to an “armed solution,” legislators, bishops, intellectuals, representatives of NGOs and indigenous individuals demanded the implementation of the San Andrés accords (Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture signed by the EZLN and the federal government in 1996). The participants in the forum stressed that, in spite of indigenous reform in 2001, the indigenous of Mexico continue to go without their basic liberties: they are discriminated against, excluded, exploited, dispossessed of their resources and lands; they go without legal justice; they lack education and access to health-care.

Before the beginning of the forum, José Narro claimed that “The federal government ought to provide genuine indicators that it is willing to sign the San Andrés Larráinzar accords, because otherwise it would be too late for there is evidence that the EZLN and other groups in the country would return to armed struggle.”

Prior to this, on 8 March, some 500 women and men—adherents to the Other Campaign—engaged in a protest in observance of International Women’s day in the Cathedral plaza of San Cristóbal de las Casas. They denounced “the war that the bad governments direct by means of shock troops paramilitary groups, and their military forces, in which rebellious women are converted en targets, exploitation, and the bounty of heartless men […]. The bad governments use their power to control the mass media, fabricate stories, and hence hide their strategy of terror and death. But the women and men who struggle clearly know that their intention is to create conditions for a military intervention against the support-bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, communities and organizations of the Other Campaign, as well as all those who impede capitalist interests that solely seek to benefit the richest in place of the people and life itself.”

Chiapas: Attention to symptoms, not roots, of conflicts

Many examples exist of conflicts in Chiapas that have over the past decade been recycled without attention being given to dealing with their roots or the legitimate demands that at times drive them. We give a few examples at the state level that illustrate impunity together with criminalization of rights-defenders (including international observers), as well as the role played by the media in this context.

Ranchería Amaytic

Five tzeltal campesinos, EZLN support-bases, were imprisoned in the municipal jail of Ocosingo starting on 11 May, but they were released without charges the following day by the authorities. They had initially been arrested by residents of the ejido Peña Limonar, and later were transferred by the State Preventive Police to be placed under the charge of the Public Ministry.

The La Garrucha Good-Government Council (JBG), located in the municipality of Ocosingo, denounced this detention on 10 May together with the disappearance of 9 other Zapatistas from the Ranchería Amaytic community, in the autonomous municipality of Ricardo Flores Magón. In its communiqué, the JBG found “the three levels of government: FEDERAL, STATE, AND MUNICIPAL” responsible for the events, as they had failed “to attempt to solve this problem.”

The conflict dates back to at least August 2002, when two Zapatista authorities were killed. The perpetrators were forced to go to live in Peña Limonar. According to La Garrucha, in March 2010 they tried to return to Amaytic occupying land by force and generating new conflicts.

The Montes Azules nature reserve

Since at least 2002, evictions—some negociated, others violent—have been carried out in the nature reserve of Montes Azules. In January of this year the communities of Laguna El Suspiro (also known as El Semental) and Laguna San Pedro (or San Pedro Guanil) were forcibly removed. The State has announced plans for the future evictions of seven communities that constitute some 3000 hectares.

Amidst all this, on 5 and 6 March there was held the “Montes Azules Social Forum” in the Ejido Candelaria, municipality of Ocosingo; about 200 people, including indigenous individuals who could soon be expelled as well as representatives from social organizations from the rest of the country, attended the event. The final declaration emphasized that “No persons, communities, or people can be deprived of their rights, especially the right to life, to human security, and free self-determination due to their residing in a natural protected area.” Recognizing that “one of our great challenges is diffusing our work and proposals in the media, so as to change the image that governments promote which present us as ‘predators’ and ‘destroyers’ of nature.” The declaration stresses that “Our strategies seek to articulate the political struggle with juridical defense, the sustainable management of natural goods, and the construction of projects of good-living.”

For its part, the Good-Government Council “Towards Hope” of the border-jungle region of Chiapas located in La Realidad denounced in a 30 April communiqué that “Calderón is planning new evictions in Zapatista communities, thus opening a breach that would enclose the Montes Azules biosphere; these are the plans of the three types of bad government: municipal, state, and federal.” The JBG added that “for us, the land is for s/he who works it; therefore, this JBG publicly condemns the events that are taking place. In light of this situation, we announce that, as the EZLN, we will not allow a single other eviction; we will not tolerate these actions, much less stop. We will defend our land whatever happens because for us, the land is not for rent, let alone to be made an object of sale.”

Chenalhó

On 9 March, the civil organization Las Abejas released a communiqué in which it presented its position to the call to dialogue on the part of the state government that was reiterated in a paid advert published in various media on 27 February.

Amidst the concern expressed in the official bulletin regarding the presence in the region of Acteal of foreigners from Pakistan, India, Peru, Spain, and the United States, who are claimed to have requested that Las Abejas refuse governmental programs, Las Abejas assert that “we tell the governor that his ears have provided him with erroneous information. Human-rights observers have also come from Germany, Argentina, Chile, Sweden, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Norway, Japan, Australia, Guatemala, and many other places. If he doesn’t know, the Acteal massacre and the responsibility of the government for such is recognized on the five continents. But the government shows its racist mentality, as it has done since the EZLN’s uprising: ‘if the indigenous decide on something, it must be that foreigners are directing them, since they don’t know how to think for themselves.’ And after insulting us so, do they expect us to sit down to dialogue with them? We tell the governor that we do what our hearts and consciences tell us when we reject support and productive projects and when we disbelieve the government’s false promises. We see what is said in the government’s acts, not its words; we don’t need foreigners to tell us what our own eyes can see.”