IN FOCUS: Children and adolescents in Mexico – an uncertain future

24/11/2014SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (From mid-August to mid-November 2014)

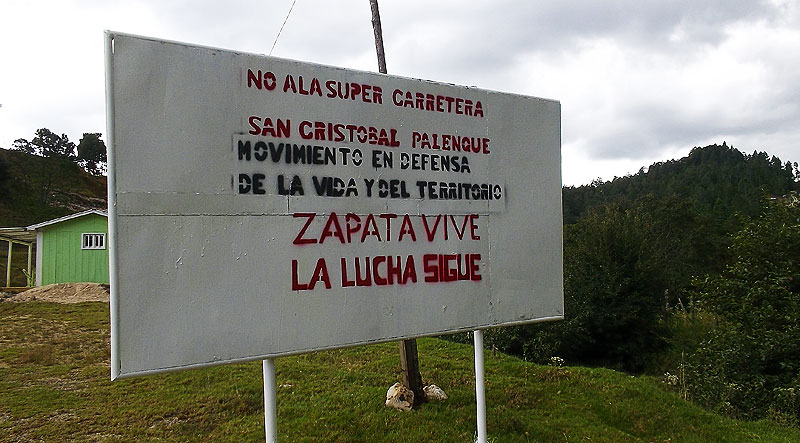

24/11/2014“It does not bring development for the original peoples.

Only death, depression, division. Only money for the wealthy transnationals.”

(Meeting in ejido Los Llanos, San Cristobal de Las Casas, October 2014)

In November 2013, the Secretary of Government of Chiapas, Eduardo Aguilar Ramirez, affirmed that there would be “no going back” in the project to build a mega-highway that would go from San Cristobal de Las Casas to Palenque, two of the most important tourist centers in the state. In the time since this declaration, communities opposing the project decided to form the Movement for the Defence of Life and Territory. The project is part of the National Infrastructure Plan and was already part of the Plan Puebla Panama (2001-2007). There has been little official information so far. In November 2013, Ramirez Aguilar added that “the affected parties will be compensated, there is no other way. Some of them can get social benefits, improved housing, productive projects”. He also stressed that “when public utility works are constructed, as in this case, the government may expropriate and compensate, but we are favoring the route of politics and dialogue.”

© SIPAZ

Although the final route has not yet been published, municipalities such as Huixtán, Tenejapa, Oxchuc, San Juan Cancuc, Ocosingo, Chilón, San Cristóbal and Palenque would be affected. According to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, ratified by Mexico, indigenous peoples potentially affected by a project have the right to a free, prior and informed consultation. In this case, the indigenous population has not been integrated into the development of the project.

The definition of development for the peoples can be very different from the governmental or business concept. The peoples have specific needs, which in many cases, are far from the idea of entering the market for tourism or ecotourist projects. Furthermore, the construction of the highway will involve damage to the environment, crops and homes which line the road from San Cristóbal-Palenque.

We must appreciate that a state so rich in natural resources is of great interest to the business sector, which has had serious difficulties in accessing these resources due to the opposition and distrust of the peoples. In January 2014, the Secretary of the Government of Chiapas said that “we cannot bring investment if we do not have the highway infrastructure; the first thing the private sector asks, whether it is foreign or domestic, is whether there are good roads and highways, and in Chiapas we have very few roads and highways.”

So far in 2014, from gatherings and community assemblies, several facts have emerged which violate the peace of the peoples and have led to a growing opposition to the project. In January 2014, the ejidatarios of Los Llanos, in the municipality of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, filed an “amparo” (request for legal protection) against the project, and they stated that, in November 2013, a representative of the city council of San Cristóbal came to their community “to threaten that the highway would cross the common lands, and if the community objected, the authorities of the community would go to prison and they would bring the army to start the construction works.” Los Llanos and the community of San José El Porvenir, Huixtán reported that “we are (not necessarily) against the highway, but we will be if they take away our lands, which are of fundamental value for the life of our community”. At the same time, they denounced that the government “has not come to ask if we give permission or not, they are simply saying that the highway will pass through”. “They have offered us other lands in Rancho Nuevo, supposedly for us to relocate to, yet these lands are in dispute because they belong to Mitzitón. We do not accept them, because to do so would involve conflict with our indigenous brothers who own them,” the ejidatarios explained. “They have told us that the road will go ahead by force, whether or not we want it to. They are looking to buy the community leaders, they refuse them infrastructure projects, such as pavements,” they said.

© SIPAZ

In July 2014, more than 15,000 people marched in 10 municipalities in Chiapas against the highway project. In August, an extraordinary assembly was held in the ejido San Jerónimo Bachajón, municipality of Chilón, where some 1,800 ejidatarios rejected the construction of the highway. They denounced that the ejidal commissioner had been harassed and pressurized to sign the authorization for the mega-highway, and that his son was fired from his job at a state government office on the grounds that he could only return to his post once his father had accepted the project.

In Candelaria, in the municipality of San Cristóbal, the ejidal authorities explained that the city council summoned them to inform them of their intention that the road should run across their land and to ask them to sign a document approving the project. The delegate of the Government of Chiapas assured them that neighboring communities had already accepted. After the meeting, the ejidatarios went to visit several communities and found that “the other communities do not agree (with the project).” “We were not given information, they just tried to force us to sign, but we did not want to,” they declared.

In subsequent months, days of mobilization were held. In many communities signs and banners were placed. On September 17, there took place in Laguna Suyul, a sacred place in the Highlands of Chiapas, a ceremony and joint declaration from more than 2,000 people from 14 municipalities in opposition to the mega-highway. The final declaration stated that “we will defend the environment, the web and the veins of mother earth; rivers, lakes, springs, mountains, trees, caves, hills. We will defend the lives of animals, sacred places, the ecosystem of mother nature and human life.” It was agreed: total rejection of the construction of the mega-highway; to make a plan of resistance (including pilgrimages, occupations and mobilizations); to send letters to embassies, organizations that care for the environment and to the authorities.

The mega-highway is one more example in Mexico and Latin America, of where business interests collide with indigenous peoples who understand “development” as respect for “life”.