ANALYSIS: Mexico: growing polarization

30/05/2008

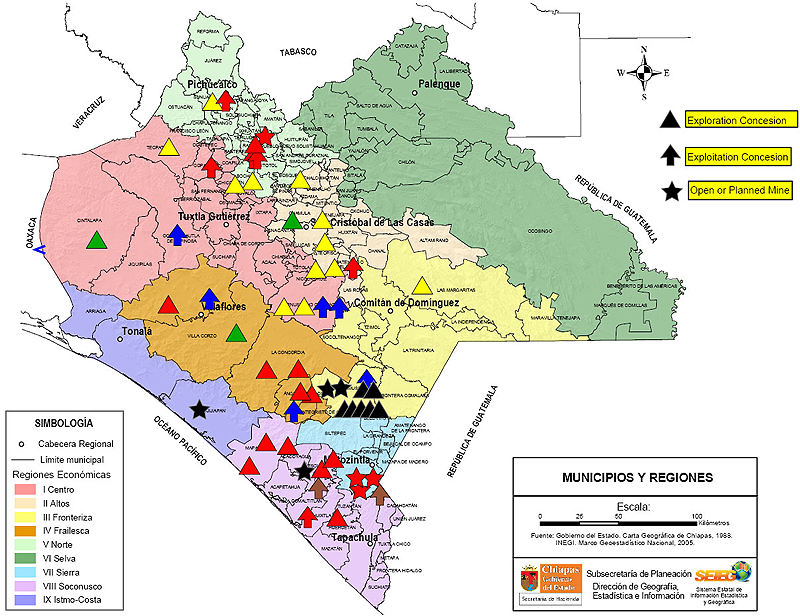

IN FOCUS : Mining in Chiapas – A New threat for the survival of indigenous peoples

29/12/2008The “war on drugs” is by no means a new phenomenon in Mexico however, since the controversial election of Felipe Calderón to the presidency in 2006, the issue has taken on a much higher profile. During the previous administration, under Vicente Fox, some 9,000 people were killed in drug-related violence and the rates have only risen since Calderón took office(1).

President Calderón has taken it upon himself to engage in a major campaign in an attempt to crush the drug cartels in Mexico. As of December 2007 he, along with the Mexican Congress, had approved $2.6 billion and 30,000 troops to support this new campaign(2). Calderón has also asked for support from the US government in the form of the so called Merida Initiative.

While the Merida Initiative is a relatively new proposition, it has its roots in a much longer trajectory of economic and security policies between the US and Mexico. The initiative appears to be closely linked to the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (SPP), which according to the official website is “…a White House-led initiative among the United States and the two nations it borders – Canada and Mexico – to increase security and to enhance prosperity among the three countries through greater cooperation,”(4) . The SPP has been formed through a series of private talks held between the three heads of state along with representatives of major corporations from the three participating countries.

In June, 2008 the Deputy Chief of Mission of the US Embassy in Mexico, Leslie Bassett, made the connection between the two policies clearer as she proposed that the Merida Initiative be integrated into the SPP. Through this connection with the SPP, the plan also has ties with much older policies including the North American Free Trade Agreement or NAFTA. Thomas Shannon, Sub-Secretary of Western Hemisphere Affairs for the US State Department, made this association apparent when he stated, “…as we have worked through the Security and Prosperity Partnership to improve our commercial and trading relationship, we have also worked to improve our security cooperation. To a certain extent, we’re armoring NAFTA.”

The Merida Initiative, armoring NAFTA?

The initiative was originally proposed to the US Congress in October 2007 as a $1.4 billion counter-narcotics package and was tagged to the Iraq supplemental funding bill as an appropriations amendment in order to expedite its passage though the US Congress for the 2008 fiscal year(5). It contains no provisions for cash payouts and in fact has no text regarding the spending plan for the bill however there has been speculation that the funding will go towards the training of law enforcement and military forces as well as a significant amount of hardware, which may include various types of aircraft and telephonic monitoring equipment for Mexico and Central America(6).

As pointed out by Laura Carlsen, director of the Americas Policy Program at the Center for International Policy, “The war on drugs model has always had this as an unspoken objective: to strengthen the executive power…(7)“ and this fits neatly within the agenda of the Bush administration which has fought for the accumulation of powers within the executive branch for the past eight years. Many members of the US Congress were frustrated with the Bush administration upon receiving the initiative as they felt there had been a serious lack of consultation with them on the initiative’s contents. Because the plan is not a treaty or formal agreement between the two countries, it has not been subject to approval by the Mexican Congress.(3) This left the Mexican Congress and civil society with little or no recourse on the initiative.

Despite the fact that the funding in the Merida Initiative is aimed at Mexican entities, the vast majority of the funding will most likely go to US military contractors such as Blackwater, KBR and Halliburton(8). In effect all of the funding will remain in the US under a plan that takes advantage of the violent drug trafficking issue in Mexico to create economic benefits for US companies. However, US government agents, such as those from the US Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms, could also be deployed in Mexico under the auspices of training the Mexican security forces and tracking the flow of arms from the US to Mexico (through Operation Gunrunner). These facets of the initiative implicate an issue of sovereignty in Mexico, especially when viewed against the backdrop of historic US/Mexico relations.

The appropriations bill eventually passed in the US Congress on June 26, 2008 though the budget was slimmed down and the majority of the human rights conditions were abandoned. The final version includes $400 million in anti-narcotics training, judicial reform and hardware for Mexico and another $65 million slated for Central America, Haiti and the Dominican Republic for the 2008 fiscal year(9).

Militarization and the impact on human rights

It is important to note as well, that the Merida Initiative was originally called Plan Mexico. However this name congers up memories of a similar plan that was implemented through a bilateral anti-narcotics initiative between the US and Colombia in 2000 known as Plan Colombia. In reality there are many similarities between the two plans especially in terms of the funding provided by the US to enhance public security forces. In eight years of Plan Colombia, the US has spent some $6 billion, 76% of which has gone towards military operations and equipment.(7)

Despite all of the funding and support that Plan Colombia has boasted over the past eight years, little has changed on the ground in Colombia in regards to drug trafficking. Studies show that the number of coca fields in the country have remained constant or increased.(7) Human rights violations continue to be a major issue as well, including the displacement of entire communities and numerous civilian deaths as a result of the intense militarization supported by the US.(7) In addition, the Center for International Policy has estimated that some 35% of the funding in Plan Colombia for 2007 went toward “non-drug missions,” and it is speculated that much of that funding actually goes toward counter-insurgency missions.(10) While the Merida Initiative does seem to imply a “Colombianization” of Mexico and Central America, it appears that politicians within both the Bush and Calderón administrations decided to change the name of the plan giving it a public relations polish.

Perhaps one of the most alarming issues with respect to the Merida Initiative is the lack of binding human rights conditions associated with it. In the original plan, there were minimal conditions tacked on to the bill that were severely cut and very nearly dropped all together. The conditions that do remain are weak at best. Those conditions, which apply to a mere 15% of the entire funding package, were included in the final bill voted into law at the end of June 2008 and provide for the establishment of a commission to receive and investigate complaints on misconduct on the part of the police or military entities; a periodic consultation between the Mexican government and human rights NGOs; the implementation of civil trials in cases of violations by member of the military; and a ban on the use of testimony acquired under torture.(9) In reality these conditions have no teeth as illustrated in the case of testimony acquired under torture. This condition does not say anything about the actual use of torture but rather the restriction of the use of testimony acquired under torture.

These requirements, soft as they are, may still be a challenge for the Mexican government and public security forces. The not so distant past of Mexico is riddled with atrocities such as the “Dirty War” of the 1970’s, which according to a former general of the Mexican Army, José Francisco Gallardo in an interview with the Mexican daily La Jornada in June 2008 (a major proponent of human rights within the military as well), has never really ebbed as indicated by the rising rates in grave human rights violations throughout the country including torture and arbitrary detentions.

The US State Department itself has also cited corruption, kidnapping, extortion and impunity within the Mexican police forces in its latest human rights report on the country.(9) And the violence in the country has not abated even with the increased financing for the war on drugs in Mexico. If anything it has increased. Radio Fórmula in Mexico reported that in June of 2008 alone, some 468 civilians were killed in Mexico due to drug related violence in comparison with the 509 civilians who were killed in Iraq during the same period.(11)

Equally troubling are the implications that increased support for the military could have on social protest. In a report released in September of 2004 by the Center for International Policy, this preoccupation was highlighted, stating, “Too often in Latin America, when armies have focused on an internal enemy, the definition of enemies has included political opponents of the regime in power, even those working within the political system such as activists, independent journalists, labor organizers, or opposition political-party leaders.”(12)

While the military model in the fight against drug trafficking has long proven inefficient and has even been shown to increase violence and concentrate executive powers(13), the bulk of the financing laid out in the Merida Initiative will in fact go to the Mexican military and police forces. In 2008 alone, Calderón increased spending to improve security forces in combating drug trafficking to some $4 billion.(2) Even the current Republican candidate for the US presidency, John MaCain, has stated in the past that “There is no evidence that the U.S. military’s involvement in the war on drugs has reduced the flow of narcotics into the country.” Already the Mexican military is involved in major anti-drug trafficking operations in eleven states(14) including Guerrero, Michoacán, Tamaulipas and most recently in Chihuahua(15).

The Mexican military is also performing operations that would normally fall under the jurisdiction of law enforcement agencies, creating a situation ripe for human rights violations due to the fact that military personnel are trained for war scenarios, in which the object is to kill an enemy, not to maintain public order, as demonstrated in a study published by the Centro Prodh based in Mexico City.(13) Public opinion polls administered in states where the military has carried out these operations have shown that support for such intervention has weakened.i In addition, many soldiers have deserted the army in favor of higher paid positions within the drug cartels themselves,i demonstrating a troubling link between the military and drug traffickers.

The military fortification that the Merida Initiative will provide is likely to lead to an increase in the number of human rights violations. The Mexican National Commission on Human Rights has called for the military’s withdrawal in combating drug trafficking.(1) The military has a long history of human rights violations and since the beginning of its involvement in the drug wars, the violations have not ceased as there have been reports including, but not limited to, fatal shootings, rape and kidnappings as described in the 2007 Mexico Human Rights Report of the US State Department.(16) The army has traditionally preferred to prosecuted these cases in military tribunals leaving the victims little recourse.(16) There are also claims that these violations are founded in the training received by members of the military in the US or the Canal Zone of Panama.(1)

The Merida Initiative, judicial reform and the criminalization of social protest

Reforms to the judicial system in Mexico also play a large role in the funding provided by the Merida Initiative. The initiative stipulates that a percentage of the funds will go towards training and equipment to strengthen judicial reforms which amount to a harmonization of the Mexican judicial system with that of the US. Many of these changes have already taken place in a constitutional reform that was approved by the Mexican Congress on February 26, 2008. These reforms can be summarized as “establishing the presumption of innocence, allowing for oral trials, imposing limits on pre-trial detention, suppressing evidence obtained through coercion, improving access to legal counsel, and enhancing the police’s investigative capabilities.”(17)

While many of these reforms appear beneficial, there are others that are of great concern to human rights defenders in Mexico. These other reforms include a revised definition of organized crime to include “an organization made up of three or more people to commit crimes in a permanent or repeated manner;” an administrative detention (arraigo) of 40 days with the option to extend the detention for a total of 80 days before charges have been made; and a compulsory detention that “is mandated for certain specific crimes such as organized crime… and serious crimes that the law determines are against the security of the nation, the free development of the entity and the public health.”(18)

All three of these reforms can easily be applied to social activists and organizations creating an environment for the criminalization of social protest. The new powers that these reforms confer on law enforcement agencies and prosecutors creates an ample margin for human rights violations especially in the case of arraigo in which police will have suspects at their disposal and may engage in torture to obtain information as has been previously documented in Mexico.(19)

There has been great resistance on the part of Mexican politicians, judges and civil society with regard to US involvement in Mexican judicial affairs.(7) Many see the situation as an infringement on Mexican sovereignty. Miguel Sarre, a professor at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM), points out that the real issue lies within the Mexican judicial system itself stating, “These realities and concerns illustrate the fact that the crucial problem is the willingness and ability to combat impunity, more than the lack of helicopters, planes and other sophisticated equipment.”(20)

The horizon of the Merida Initiative

The future of the Merida Initiative looks to be long and perhaps arduous. While the original plan is composed of three years of funding, recently, Senator Patrick Leahy (Democrat from Vermont) stated that he believes that should the initiative show results, it will become a “multi-year commitment.” This implies that regardless of who wins the US presidential elections coming up in November, 2008, the incoming president will quite possibly be tied to Bush’s security legislation for years to come. The future for the fight against the Merida Initiative by the civil societies of both the US and Mexico becomes bleaker in light of Democratic nominee Barak Obama’s comments that the plan does not provide sufficient investment in combating drug trafficking. In fact the US Congress is currently considering an extra $400 – $470 million to be approved for the 2009 fiscal year under the initiative.(20)

It is obvious that the US is mandating and looking to continue a cycle of economic benefits for the private military sector in the US through this so-called bi-lateral initiative. With that in mind it is important to remember the words of former US Secretary of State under Eisenhower, John Foster Dulles, who while attending the inauguration of Mexican president Adolfo Lopez Mateos in December 1958 stated, “The United States of America does not have friends; it has interests.”

… … …

- Roderic Ai Camp, “Role of Military to Military Cooperation and the Implications and Potentials Risks to Civil-Military Relations,” Testimony to Congressional Policy Forum 9 May 2008: 3, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Ray Walser, “Mexico, Drug Cartels, and the Merida Initiative: A Fight We Cannot Afford to Lose,” The Heritage Foundation, [Washington], 23 Jul. 2008, (11 Aug. 2008) (Return…)

- Carl Meacham, “The Merida Initiative: Guns, Drugs and Friends,” A Report to Members of the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate 21 Dec. 2007: 5, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- United States, Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America, SPP Myth and Facts (Washington: 2008), (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Jennifer Johnson, “The Forgotten Border: Migration & Human Rights at Mexico’s Southern Border” Latin American Working Group, January 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- United States, US Congress, Merida Initiative to Combat Illicit Narcotics and Reduce Organized Crime Authorization Act of 2008, Title I, Sec. 113, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Laura Carlsen, “A Primer on Plan Mexico,” Center for International Policy: Americas Policy Program, 5 May. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- United States, Department of State, PSC – NAS Policy Advisor, Mexico City, Mexico, 25 Jun. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- United States, US Congress, Military Construction and Veterans Affairs and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2008, Chapter 4, Subchapter C, Sec. 1406, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- “How much U.S. security aid is not counter-drug? Perhaps 35%,” Center for International Policy: Plan Colombia and Beyond, 9 Jul. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Fórmula de la Tarde, Radio Fórmula, Mexico, 1 Jul. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- “Blurring the Lines: Trends in U.S. military programs with Latin America,” Center for International Policy, September 2004, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- “Military Abuses in Mexico,” Prodh Briefing, Centro Prodh, 14 Jul. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- United States, US State Department, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report: Mexico, Sec. III Country Actions Against Drugs in 2007, March 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Eric Olson, “Six Key Issues in United States-Mexico Security Cooperation,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Mexico Institute: Security Initiative, May 2008: 7, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- United States, US State Department, Mexico: Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 11 Mar. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Andrew Selee, “Overview of the Merida Initiative,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, May 2008: 3, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- Mexico, Secretaría de Gobernación, Decreto por el que se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos de Mexicanos, 18 Jun. 2008 (Return…)

- Miguel Sarre, “Mexico’s judicial reform and long-term challenges,” Presented at the Policy Forum: U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation and the Merida Initiative, conveyed by the Mexico Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars. Capitol Building, Washington, D. C., 9 May. 2008: 3, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)

- “Repeat Offense! Congreso Plans to Double Merida Funding!” Witness for Peace, 25 Jul. 2008, (31 Jul. 2008) (Return…)