We need your support. Your contribution makes it possible for SIPAZ to continue offering international accompaniment in the regions of Chiapas, Oaxaca and Guerrero.

Facts About Chiapas

Indigenous Peoples :

Most populated state in the country for number of inhabitants

of the national population

Is the median age

Según el censo del INEGI de 2015

Chiapas, like other states in south eastern Mexico, has a multi-ethnic and multicultural population.

of the population of the state

According to INEGI 2015, some 1.361.499 people older than three years of age speak an indigenous language, which represents 27.94% of the population of the state. It is worth noting that the percentages vary according to the criteria used in the research. One the one hand “visible” criteria, such as speaking an indigenous language or wearing traditional dress, are established, while on the other prioritize an individual’s self-identification as indigenous prevails.

12 of the 62 officially recognized indigenous peoples in Mexico are found in Chiapas.

The population over three years of age who speak an indigenous language is mainly divided into 5 groups:

Tseltal 38,2%38%

Tsotsil 34,5%34%

Ch’ol 15,9%15%

Zoque 15,9%3%

Tojolabal 4,4%3%

The Mame, Chuj, Kanjobal, Jacalteco, Lacandon, Katchikel, Mochó (Motozintleco), Quiché and Ixil groups comprise the remaining indigenous population of the state.

29.34% of the population aged three years and over who speak an indigenous language cannot speak Spanish. It is the state with the highest monolingualism in the country.

Sources: INEGI conociendo Chiapas, Octava Edición 2018; Encuesta Intercensal del INEGI 2015. (INEGI Knowing Chiapas, Eighth Edition 2018; INEGI 2015 Intercensal Survey).

Social Inequalities :

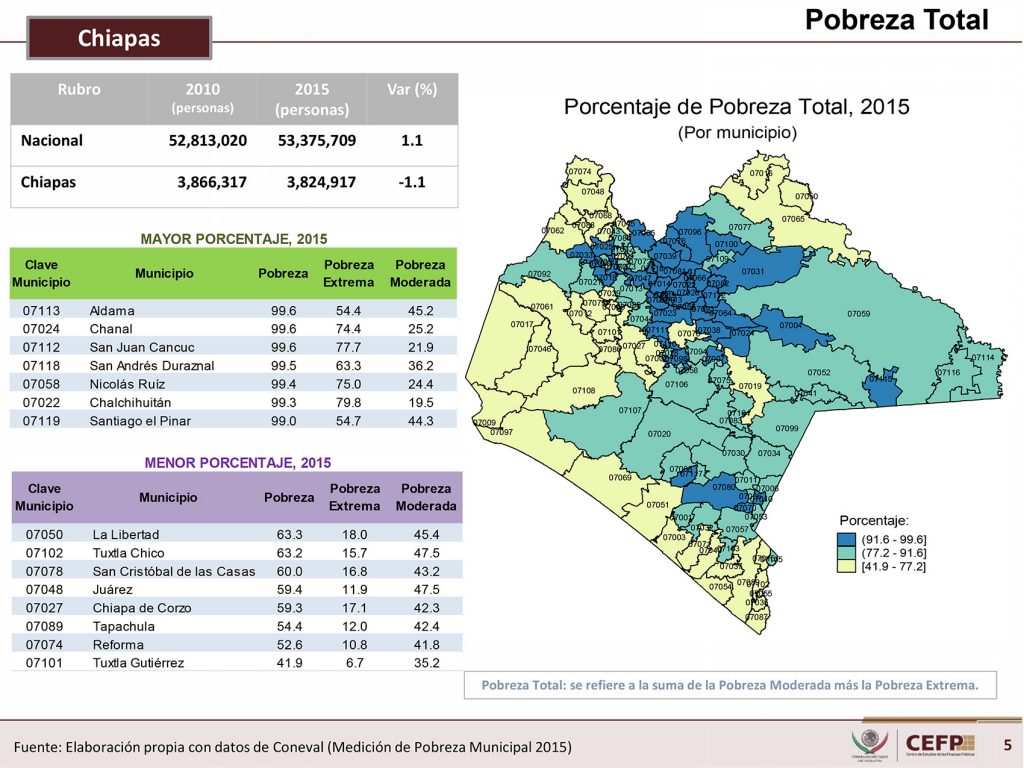

In 2015, Chiapas ranked second in the degree of marginalization at national level, preceded by Guerrero and followed by Oaxaca. It has 34 municipalities in the category of very high marginalization and 69 in a situation of high marginalization, which are located mainly in The Highlands and The Jungle. This means that 58.47% of the population is living in a high degree of marginalization and 28.81% in a very high degree. Only two municipalities in Chiapas are very low or low marginalization and only 6% of the Chiapas population is neither poor nor vulnerable to social deprivation. The municipality of Sitalá, located in the North-Jungle zone, occupies the first place within the most marginalized municipalities at the state level and sixth place at national level.

Chiapas ranked second in the degree of marginalization at national level, preceded by Guerrero and followed by Oaxaca.

in the category of very high marginalization

in a situation of high marginalization

which are located mainly in The Highlands and The Jungle

The municipality of Sitalá, located in the North-Jungle zone, occupies the first place within the most marginalized municipalities at the state level and sixth place at national level.

We find in Chiapas :

are very low or low marginalization

is neither poor nor vulnerable to social deprivation

Sources: Medición de Pobreza Municipal CONEVAL 2015; CONEVAL 2018; Declaratoria de Zonas de Atención Prioritaria 2020; CONAPO 2015

Income :

- 13.3% of the active population in Chiapas does not receive an income (almost double the national average).

- 34.1% of the economically active employed population (EAP) earn nothing more than a minimum wage. Although the part of the population belonging to this group has decreased compared to 2010, more than double the national average, Chiapas continues to occupy the first place at national level in terms of the EAP that receives less than a minimum wage.

- In general, average incomes are lower in rural and indigenous areas. In this sense, it is relevant to mention that 49.72% of the population is concentrated in urban areas and 50.28% in rural areas; at the national level the data is 78% and 22% respectively.

- Regarding the proportion of EAP by activity sector, Chiapas continues to occupy first place in the primary sector (36.9%); and last in the secondary sector (14.5%) and tertiary at national level (48.3%). The strong participation in agricultural activities is even higher in the indigenous part of the state where the subsistence agriculture model dominates, which does not allow agricultural surpluses with which to have significant economic income.

- Although the current minimum wage at the federal level is 123.22 pesos, the average income per hour worked for those employed in Chiapas is 21.1 pesos.

- The Labor Informality Rate for Chiapas is 79.2% of the active population.

Sources: Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo INEGI 2015, Encuesta Intercensal INEGI 2015, comité Estatal de Información Estadística y Geográfica de Chiapas

- According to data from the State Committee for Statistical and Geographic Information of Chiapas in 2018, Chiapas ranked 16th at national level in terms of attracting remittances. According to the Ministry of Economy, in 2019, remittances amounted to 815 million dollars. In the last ten years, the amount of remittances in the country increased in general by 60.02%, while in Chiapas the increase was 64.97% in the same period.

Sources: “Chiapas, Ingresos por Remesas Familiares”, Comité Estatal de Información Estadística y Geográfica de Chiapas, 2020

% of the active population in Chiapas does not receive an income

% of the economically active employed population (EAP) earn nothing more than a minimum wage

The current minimum wage at the federal level is :

$ 123.22

Right to Adequate Housing :

A large percentage of households in Chiapas do not meet the minimum conditions for adequate housing.

Lack of housing

Chiapas is the state that registers the highest proportion of the population with lack of housing (78.2%).

Of the homes are overcrowded

Almost double the national average.

Chiapas is still the state with the highest number of inhabitants per dwelling, although the average figure per dwelling was reduced to 4.02 people.

Have piped water inside the home

Have electricity

Of the occupants of the dwellings have drainage connected to the public network

Of the homes have dirt floors

For several years, there has been a social movement in resistance to high electricity chargesin the state. It considers free access to electricity as a human and constitutional right, since electricity comes from the natural resources of the territory where the majority of the population lives. In 2009, many joined the National Network of Civil Resistance to High Electricity Rates. By that date, 40 percent of the electricity users in the state, between individuals and municipal authorities, remained unpaid.

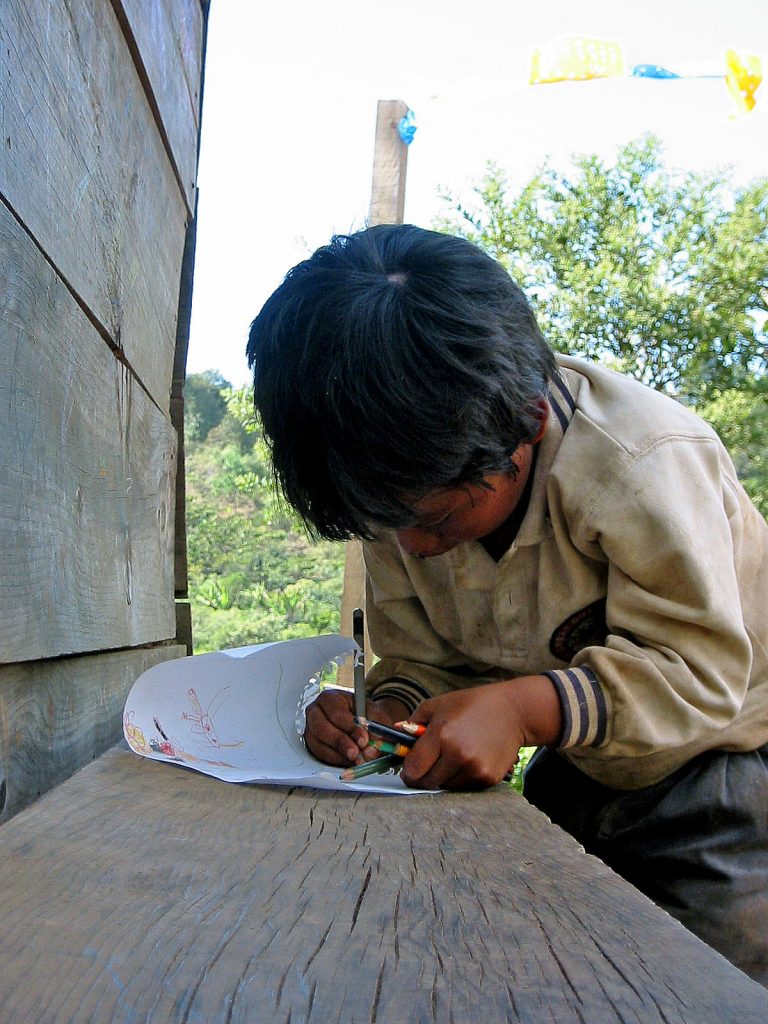

Education :

In Chiapas, for many people, especially indigenous people, and even more so, women, the right to education is not met for various reasons. The situation of poverty forces children to work to improve the family economy. Furthermore, many isolated communities do not have the adequate infrastructure to facilitate education (lack of classrooms, furniture, books, basic services, lack of teachers, overcrowded classes, lack of bilingual focus,…).

Of the population has an educational gap

The illiteracy rate is

of the population

Compared to the national total of 4.3%.

The average schooling in Chiapas is

(9.2 at the national level)

Being the entity with the lowest average schooling recorded.

Of the population over 15 years of age does not have any level of education

Of the population aged 15 to 17 do not attend school

Of students complete upper secondary education

Of students complete higher education

Of the students in Chiapas have basic services at their school

Study in schools with buildings made with lasting materials

Have class benches and blackboards

Sources : Medición de la pobreza CONEVAL 2018; Encuesta Intercensal 2015; Diagnóstico del Derecho a la Educación CONEVAL 2018

Health :

Of the population does not have access to health services

Has deficiencies in terms of access to social security

Of children under one year of age die per thousand live births, while the national average is 11.7

At national level in terms of infant mortality

Per 1,000 inhabitants (last place at national level)

Sources : INEGI 2017; CONEVAL 2015; . Medición de la pobreza CONEVAL 2018

Malnutrition and its consequences

Of the Chiapas population suffers from lack of access to food

In the 17 municipalities that make up the Highlands of Chiapas :

Chronic malnutrition in Chiapas is

Although at national level 33% of children and adolescents between five and 12 years of age are overweight and obese, Chiapas records 24% of students of the same age range with short stature.

Sources : Medición de la pobreza CONEVAL 2018

Maternal Mortality

The calculated maternal mortality rate is

Deaths

per 100,000 estimated births,

being the state with the second most cases at federal level

Sources : Secretaría de Salud de Chiapas 2020

The main causes of maternal death in Chiapas are:obstetric hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, complications of pregnancy or childbirth, indirect causes, miscarriages, HIV, and complications after childbirth. Many of the causes of maternal mortality in the state would be preventable by having timely quality care and a better quality of life

Sources : Centro Nacional de Equidad, Género y Salud

Childhood Pregnancies

Since 2014, Chiapas ranks

in the number of childhood pregnancies

This situation is alarming not only in the education system due to school dropouts, in addition the health sector is on constant alert, given the risks that young people not older than 13 years of age may lose their lives during childbirth or because health complications arise from health.

Sorces : Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica (ENADID)

VIH/SIDA

Between 1983 and November 2019, 11,450 notified cases of AIDS have been registered, of which 8,500 correspond to men and 2,950 to women, with a proportion of cases with respect to the national total of 5.4%.

Sorces : Centro Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del VIH y el Sida (CENSIDA)

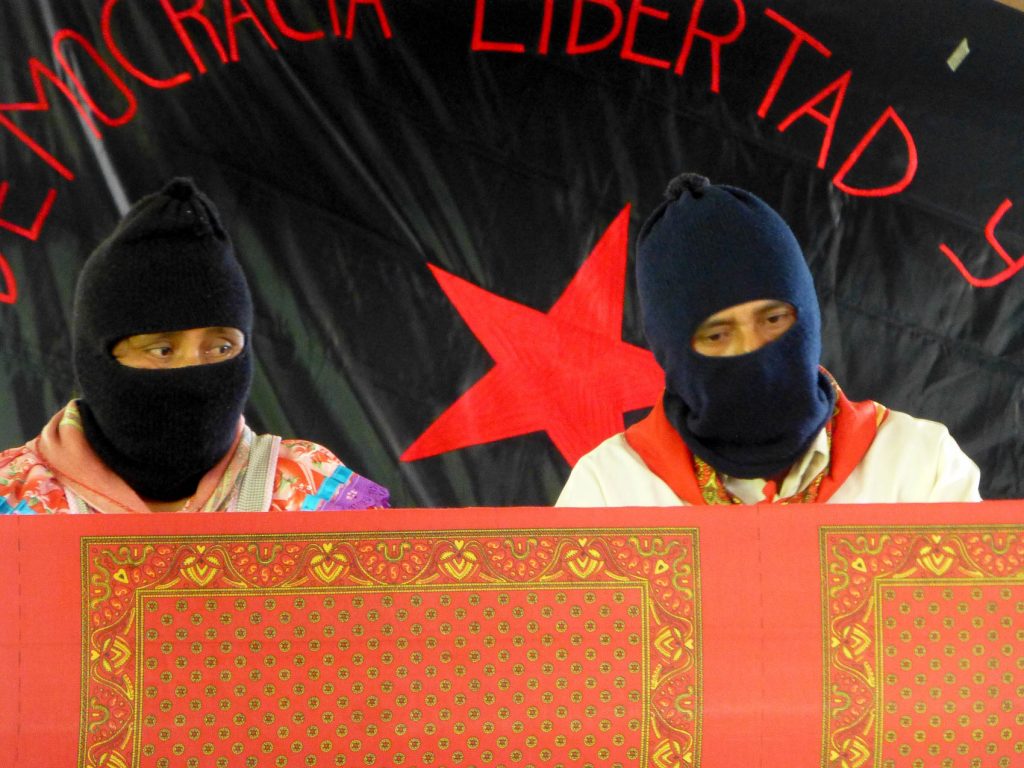

Zapatista Autonomous Health System

Due to a series of discriminatory policies, the majority of indigenous communities have not had access to the Mexican health system.

The lack of resources and the remoteness of some communities from large urban centers has led to the exacerbation and spread of easily curable diseases.

For this very reason, the Zapatistas have developed their own autonomous health system, with autonomous regional clinics in which patients are cared for by indigenous health promoters.

Land :

Of the state surface

Are lands for agriculture, urban areas, areas without vegetation and dams or lagoons;

the rest is covered by natural vegetation

Land : A Conflict of Visions

The concept of land held by the indigenous peoples is different from that of the mestizo population. The indigenous peoples continue to view the land as whole and sacred (“Mother Earth”), to be held collectively and not for sale. In Mexico, ejidos and communal lands have been the dominant form of landholding:

EJIDOS

Each ejidatario, member of the ejido, receives a parcel of land and all decisions pertaining to the ejidal land have to be made by the entire assembly of the ejidatarios.

COMMUNAL LANDS

The land belongs to all members of the community and, as a result, the benefits of the land are distributed among all members

In Chiapas, 59% of the total surface area of workable land pertains to these two types of landownership

3,552,030 hectares

Are ejidal lands divided among 3,107 ejidos, making Chiapas the state with most ejidos after Veracruz

801,752 hectares

Are communal lands

Sources : Registro Agrario Nacional (RAN) 2014

Legislation on Land: Fragmentation, Privatization and Source of Conflict

Chiapas is a state where the agrarian reform implemented after the Mexican Revolution did not take place. For a long time, the land remained in the hands of a few landowners. This fact made land one of the main factors of social conflict, which has deepened over time. The search for land generated, especially since the 50’s, a complex process of migration towards the Lacandon Jungle. To this it must be added that in the 1970s the state government decided to grant a few families of the Lacandon ethnic group more than 600 thousand hectares of the jungle without having satisfied the needs of the remaining and growing indigenous and peasant population. This is one of the factors why the Jungle today continues to be one of the most conflictive scenarios.

In 1992, Article 27 of the Constitution was amended, allowing communal and ejido land to be subject to free buying and selling (previously it was prohibited, protecting communal and ejidal land). This reform exploited social mobilization throughout the country, and its repeal was one of the main demands of the 1994 armed uprising. This reform gave rise to PROCEDE (Program for the Certification of Ejido Rights) and PROCECOM (Program for the Certification of Rights Communal).

Many civil organizations have denounced PROCEDE and PROCECOM for the divisions they have generated in the communities and ejidos, and for promoting land grabbing and sale of collective lands. For example, when the ejidos accept PROCEDE, the peasants can obtain loans, but they have to use their lands as collateral, and if they fail to comply with the loan later, they lose their lands. On the other hand, when they enter PROCEDE, they have to start paying property tax for both the plot and the site. For this reason, PROCEDE is seen by many people as a neoliberal mechanism against the peasant community through the privatization of land.

There is also much criticism of the way in which the program was “proposed”. Initially, in 1993, it was presented as a voluntary program. It has been reported that the Agrarian Prosecutor’s Office tried to impose PROCEDE in all agrarian nuclei, through pressure and blackmail with the communal and ejidal commissariats, so that they are the ones in charge of informing the people and convincing them of the benefits of this program. In this way it seems that the peasants freely decided to privatize their lands and assumed the consequences. In several places, the program was presented as a condition for those who want to benefit from other support programs in the countryside, such as PROCAMPO.

In December 2006, the government formally closed the PROCEDE program. In Chiapas, more than 2 million 880 hectares were registered. The Support Fund for Unregulated Agrarian Nuclei (FANAR) began in 2007 and operates to date, currently under the name Program for Regularization and Registration of Agrarian Legal Acts (RRAJA-FANAR), to conclude the measurement operations, certification and titling of land rights through PROCEDE.

Sources : YORAIL MAYA 4, junio de 2002; Escaramujo 94 “Radiografía de Ejidos y Bienes Comunales – Chiapas en disputa por los territorios indígenas y campesinos”, Otros Mundos, mayo de 2020

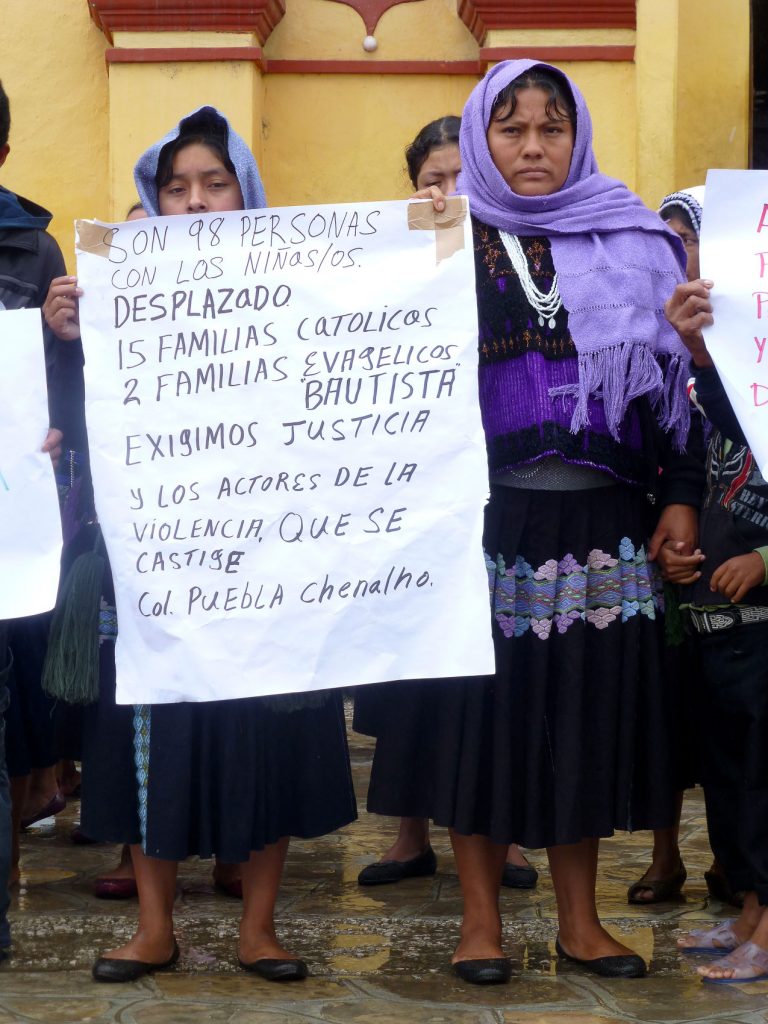

Agrarian Conflicts

Most of the multiple current agrarian conflicts in Chiapas are the continuation of old disputes, inheritance of measurement errors, of the clientelist and political use of agrarian reform, as well as of the distribution of certificates and deeds to many of the players in dispute to convenience. Conflicts over land boundaries have led to armed clashes, deaths, injuries, and sometimes massive internal forced displacement of part of the population.

"Hot Spots"

In recent decades, the main hot spots have been:

- The Lacandon Zone community and the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve.

- 115 agrarian nuclei that are in the power of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), which considers them as recovered lands, with an area of 355 thousand 769 hectares.

- At least 12 towns with 34,634 hectares, with boundary problems with community members of the municipalities of San Miguel and Santa María Chimalapas, Oaxaca.

- The Communal Assets of San Miguel Utrilla or Santa Martha of the municipality of Chenalhó disputed by inhabitants of San Pedro Chalchihuitán, a long-standing conflict that in October 2017 caused the forced displacement of thousands of people.

- The agrarian conflict over 60 hectares between the municipalities of Aldama and Chenalhó, in the Highlands of Chiapas, which since 1975 has left around 25 dead, dozens of displaced people and several people injured.

Sources : SIPAZ monitoring since 1995

Most Common Causes of Agrarian Conflict

Agrarian conflicts arise :

- Due to the lack of land when the “agrarian frontier” has already been exhausted, a phenomenon affected by population growth, the lack of spaces for agricultural use and the increase in urban areas with their irregular settlements.

- Due to ambiguities and legal voids regarding agrarian rights and titles for decades and even centuries.

- Due to overlapping plans resulting from the delivery of documents altered by the agrarian authorities.

- Over disagreements about territorial boundaries, including interstate boundaries (the case of Chimalapas with the neighboring state of Oaxaca).

- Due to the invasion of ejidal or private areas.

- Due to inadequate or negligent responses from the authorities in the resolution of said conflicts.

- Due to conflicts in the interior and between social and indigenous groups or organizations (according to the Agrarian Reform Commission of the State Congress, more than 700 organizations interact in Chiapas).

"Reclaimed Lands"

Special mention should be made of the so-called “recovered lands” of the Zapatistas after the 1994 uprising. The lands taken after the uprising are considered ‘Zapatista territory’ by their members and are considered as collective property that cannot be “negotiated”. To consolidate its control over these lands, the EZLN has promoted a policy of populating the properties taken, through the construction of settlements known as “new centers.”

“While the federal government offers legality, the Zapatista agrarian distribution is an invitation to fight for the land and join the basic Zapatista demands. What ensures their tenure is not a document but the unity of the organization. The members have an incentive to maintain unity, since otherwise they would lose access to the land.”

Source: Richard Stahler-Sholk, Reconfiguration of Spaces in a Social Movement: The Zapatista Autonomous Communities in the Selva Tseltal Zone