LATEST: Mexico – Pressure from US and Human Rights Crises

27/06/2017

ARTICLE: On the Chiapas Estate and the Neoliberal Capitalist System – Critical Reflection Seminar “The Walls of Capital, the Cracks of the Left”

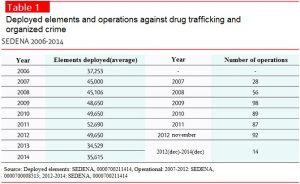

27/06/2017December 2016 marked the tenth anniversary of the so-called “war on drugs” in Mexico, during which time thousands of Army, Air Force and Navy soldiers have been deployed on the streets to fight not only drug trafficking, but also organized crime in all its aspects: arms trafficking, money laundering, extortion, trafficking of people (including migrants), kidnapping, theft, etc.

marked by a massive increase in murders and human rights violations, and a general increase in violence and insecurity. From 2006 to date, the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP in its Spanish acronym) has registered more than 213,000 murders, while the National Registry of Disappeared Persons (RNAPED in its Spanish acronym) has estimated that there have been over 30,973 disappeared in that period without counting migrants.

Within this context, the Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA in its Spanish acronym), General Salvador Cienfuegos Navara, requested a legal framework for the intervention of the armed forces in public security activities. That opened the debate on an Internal Security Act, whose proposals to date have been widely criticized for their unconstitutional character and are perceived as a threat to human rights.

Drug trafficking in Mexico

Due to its geographical location, Mexico has been used as a transit country for drugs (mainly cocaine and marijuana) between producers in Latin America, especially Colombia, and one of the main markets in the world: the United States. Nevertheless, it has not only been a country of transit but also of production. According to Luis Astorga, a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM in its Spanish acronym), the production of marijuana and opium, as well as its transformation into opiates, began in the 1960s. To explain how they managed to expand production and drug trafficking activities in the country, he said in La Jornada, “Drug trafficking in Mexico, from its beginnings has been a business of the ruling elite, in the shadow of the government monopoly held by the PRI for more than 70 years. This means that, instead of constituting a threat to government institutions, there has been collusion with the politicians who have allowed it to operate with total impunity.”

According to research by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, drug trafficking is the most lucrative activity for organized crime. Its profits constitute hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Its lucrative and illicit status makes drug trafficking a changing industry, which adapts to market demand and makes it a complex and difficult phenomenon to analyze and combat.

Growth of the cartels through recruitment of the marginalized population

Poverty, marginalization, lack of education and unemployment have been the main causes of the tendency to join crime as a means of subsistence and social advancement. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), poverty continues to increase in Mexico. In 2014, ECLAC noted that 53.25% of the population lives in poverty and 21% in conditions of extreme poverty. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) noted that the Mexican government does not make sufficient efforts to break these conditions of poverty, since budgeted expenditure for relief and social development accounts for only about a third of the average of the OECD countries. Living in the midst of scarcity, family violence, hostile environments and with the spread of narco-culture by means of music, soap operas and films, there is a perception of “success” of drug traffickers, for the money, possession of luxury goods and the company of women, such that being part of organized crime has become a tempting option. The Mexican Youth Institute (IMJUVE in its Spanish acronym) indicated that young people are even more vulnerable to being recruited by organized crime becoming cannon fodder for it.

Michoacan: cradle of the Calderon’s war on drugs

Due to its port in Lazaro Cardenas, Michoacan is a key state for drug trafficking. From September 2006, three months before Felipe Calderon Hinojosa (of the National Action Party – PAN in its Spanish acronym), took the presidency, La Familia Michoacana (The Michoacan Family) made its premiere with a bloody appearance. According to online magazine Animal Politico, the former governor of Michoacan, Lazaro Cardenas Batel, called for urgent support to combat growing crime. Calderon, a native of the state, responded with Joint Operation Michoacan, in which 4,200 elements of the Army were deployed, 1,000 of the Navy, 1,400 federal police and 50 agents of the Public Ministry. Similar military operations followed in Guerrero, Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosi and Coahuila, with which Felipe Calderon publicly decreed a full-on war against the drug cartels. In his six-year term, Felipe Calderon increased federal security spending by 50%, instead of investing in job creation, among other things, as he had promised in his election campaign.

For his part, in his first years of office, Enrique Peña Nieto, of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI in its Spanish acronym), had a less bellicose discourse, replacing “war against narcos” with “Mexico in Peace”, but that did not stop him increasing deployment and military expenditure. “If Calderon was the father of this policy, Enrique Peña Nieto is like the teenage son who wants to break away from the father but mirroring the paternal behaviors that he saw in childhood,” said The New York Times.

Public security and national security: two different concepts

In 2009, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (IACHR), in its report on citizen security and human rights, explained that despite the confusion between the concepts of public security and national security “there is no doubt that ordinary crime – no matter how serious it is – is not a military threat to the sovereignty of the State.” In 2015, in its report “Use of the Forces”, the IACHR emphasized that the police forces and the Armed Forces are two institutions that are substantially different in terms of the purposes for which they were created and in terms of training and preparation. Police forces are formed for public security, that is to say protection and civilian control; the Armed Forces focus their training and preparation on a single objective, national security, consisting of the rapid defeat of the enemy with the least number of human casualties and economic losses. Because of their national coverage and the variety of their functions, civilian police are, in theory, the state institutions most frequently associated with citizens, for which reason the IACHR called them “irreplaceable” for the proper functioning of the democratic system and to guarantee the security of the population.

Military as police: corruption continues, violence rockets

The “incapacity and corruption of state and municipal police officers who have been penetrated by organized crime” explains why the military has assumed public security functions, said retired Gen. Sergio Aponte Polito in an interview with Proceso. Studies by the Organized Crime Investigation Center indicated that more than 70% of municipal police in Mexico are corrupt, some even on the payroll of criminal groups.

That is one of the factors that explains the tendency to militarization of the police forces in the last decade. Even today, more than a third of the states are in the hands of the military as state secretaries of public security, including Guerrero and Oaxaca. According to the Mexico Peace Index 2017 of the Institute for Economy and Peace, it is in those states that security has most deteriorated in the last six years.

Furthermore, organized crime managed to infiltrate and corrupt elements of those forces. At the end of October 2008, the so-called Operation Cleanup revealed, for example, that 24 army officers, police agents, prosecutors and elements of the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) were giving official information from the public prosecutor and the DEA on investigations and operatives to the cartels in exchange for thousands of dollars per month. To date nobody has been arrested for this. Another example is that at the beginning of May of this year, eight army officers were sentenced to 26 years in prison for the crime against health in their collaboration with the Zetas criminal organization. It should be remembered that the Zetas were started by 14 former soldiers.

Failure of Calderon’s war against criminal gangs

From March 2009, the Attorney General’s Office (PGR in its Spanish acronym) offered millions in rewards to those who provided information that would lead to the capture of 37 of the top drug lords and their lieutenants. However, the arrest and annihilation of operative heads of drug trafficking did not lead to a disarticulation of the cartels, on the contrary, it generated an unprecedented crisis of violence.

Carlos Montemayor warned the same year that the country could suffer a civil war. The conflict, in effect, became a multiple war: of the Mexican State against criminal organizations; of criminal organizations among themselves, for the control of the territory, to access a growing internal market and to maintain the monopoly of the transit routes; and there were also internal conflicts in criminal organizations for assuming the vacant position of leader, often generating fragmentation and the creation of new groups. Studies of the Drug Policy Program (PPD in its Spanish acronym) of the Center for Economic Research and Development (CIDE in its Spanish acronym) revealed that drug trafficking groups grew by more than 900% during the administration of Felipe Calderon.

A bloody decade

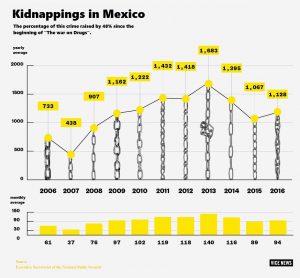

In addition to being a failure to stop the cartels, the war generated an explosion of human rights violations. The victims have not only been criminals and of the armed forces, the degree of collateral damage for innocent civilians has also skyrocketed. No state has been exempt from being part of such macabre statistics. According to Vice News only one tenth of the terror of the war against the narcos is known, since many murders and violations of human rights were never reported for fear of reprisals. CIDE figures show widespread torture and a multiplication of extrajudicial executions. In addition, criminal groups have diversified their income based on impunity: extortion increased, money laundering soared, kidnappings grew, with an intensification of those of professionals for whom ransom is not demanded but who are “enslaved” for their skills. According to the SESNSP in 2006, 733 abductions were reported, reaching a peak in 2013 with 1,683. In total, there were 12,585 in the last decade. Trafficking of persons to be subjected to sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, organ extraction, as well as Illegal trafficking of migrants and children also intensified.

Ten years after the start of the war on drugs, insecurity has spread throughout the country, drug production and consumption has advanced and in the United States, heroin deaths have become epidemic. The justification for launching this war – subdue the criminals and strengthen the state – has collapsed. The justice system is overstretched. There is no effective State policy to compensate victims for damages or to keep young people away from armed groups.

Worrying possibility of normalizing military presence and intervention

On December 8th, 2016, the Secretary of National Defense, Salvador Cienfuegos, publicly urged that the activities of the armed forces be regularized in the fight against organized crime or that a deadline be set for the Army to return to its barracks. He said that in the absence of a legal framework, the soldiers “are already thinking if it suits them to continue to confront these groups.” He argued that the military “did not study to chase criminals …” and that as an Army “we are doing functions that do not correspond to us, all because there is nobody who should do it or they are not trained.”

In response, business leaders demanded that the Mexican Army not return to the barracks until state governments have the capacity to deal with organized crime, urging the legislative branch to pass laws that give greater judicial certainty to the armed forces. Also, several legislators from PRI, PAN and PRD sent bills to the Senate of the Republic on internal security. It should be noted that none of these proposals included direct incentives for the withdrawal of the armed forces from security tasks or for the progressive strengthening of civilian police.

Faced with the possibility of an Internal Security Act being imposed in a rushed and opaque manner that could lead to the regulation of the activities of the Armed Forces, several civil society organizations called for a broader debate incorporating all points of view. The Red Todos los Derechos para Todas y Todos (All Rights for All Network) demanded a public discussion on this project. “It aims to normalize what in any democracy would be an exception […] Such a legal framework cannot simply state that what happens today unconstitutionally be normalized and made permanent. Neither should the suspension of individual guarantees so that the army can carry out the task that corresponds to the civil authority without controls and without transparency be advocated.” The National Human Rights Commission (CNDH in its Spanish acronym) also proposed that the law be subject to a wide-ranging discussion, involving “all players” and that experts be included. The UN, for its part, recommended prioritizing the design of a program for the gradual withdrawal of the Armed Forces from the tasks they are carrying out today and for a real plan for the progressive strengthening of civilian security bodies.

Main arguments against the Internal Security Act

First and foremost, the adoption of an Internal Security Act would violate the Constitution. Article 129, for example, prevents the Armed Forces from carrying out functions in times of peace that are not linked to military discipline. In addition to its unconstitutional character, an Internal Security Act would contravene the international treaties that Mexico has ratified and ignore the recommendations made by the treaty bodies. After visiting Mexico in 2014, the UN Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions noted that one of the particularly pressing problems in Mexico is the application of a military approach to the maintenance of public security. “The main objective of a military corps is to subject the enemy by using the superiority of its force, while the human rights approach, which must be the criterion for judging any police operation, focuses on prevention, arrest, investigation and prosecution, and only contemplates the use of force as a last resort, allowing recourse to lethal force solely to prevent the loss of human life,” the rapporteur said.

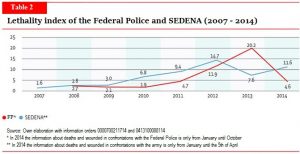

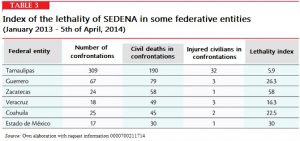

On the other hand, there is no guarantee that a law of this type would provide effective tools to reduce insecurity, as the ten-year military deployment experience did not show a decrease in violence. On the contrary, it could pose a threat to human rights. In ten years of war, more than 10,751 complaints have been filed against the Army and Navy for serious violations of human rights before the CNDH. The study “Death rate 2008-2014: confrontations decrease, same amount of deaths, opacity increases” showed that more and more civilians are killed for each civilian injured in clashes with the Army. In any confrontation between civilians and security forces, the number of dead should not exceed the number of wounded by much. Therefore, the index value should not be much higher than one. However, CIDE studies show extremely high death rates. In 2007, the Army’s death rate was 1.6 and rose to 14.7 in 2012. In the first two years of Peña Nieto’s rule, the rate dropped to 7.7 in 2013, but then rose to 2014 to 11.6. On average, from 2006 to date, the Mexican Army has killed 8 people for each one it injured. In addition, the CIDE reported that four out of ten combats were of “perfect fatality”, that is to say, only deaths were registered with no injuries.

An Internal Security Act could imply legislating “to size” for the Armed Forces without prioritizing the public interest. Some analysts point out that an initiative that arises directly from a requirement of the Armed Forces seems to be a further indication of the current weakening of civilian controls over the Army and Navy. The deputy director of the Miguel Agustin Pro Juarez Center for Human Rights (PRODH in its Spanish acronym), Santiago Aguirre, emphasized that empowering these institutions more would “risk the stability of civil-military relations, which is one of the pillars of any rule of law”.

The PRODH Center also drew attention to the danger of adopting such a regulation “given the chronic impunity prevailing in Mexico regarding human rights violations committed by the Army, in what the Inter-American Court of Human Rights itself termed “institutional military impunity.” However, the PRODH Center stressed that the design of a security policy compatible with human rights and the rule of law is possible. But this will only happen by adopting laws that include fundamental changes in the security paradigm that has prevailed in the last decade.

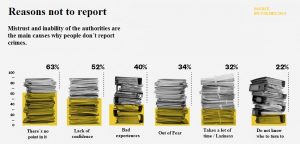

- Unreliable authorities

- Index

- Index

- Reasons not to report

- Black Numbers

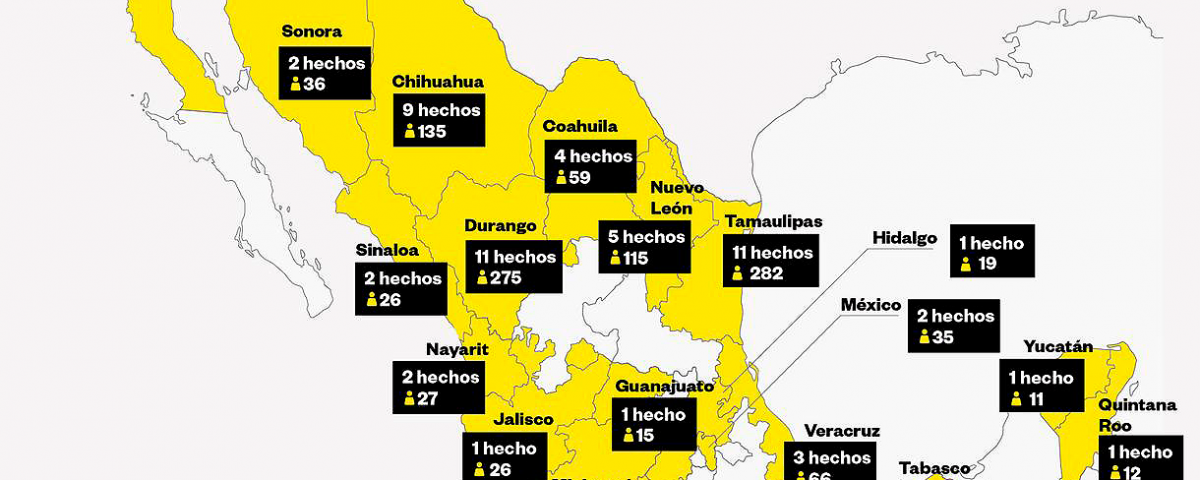

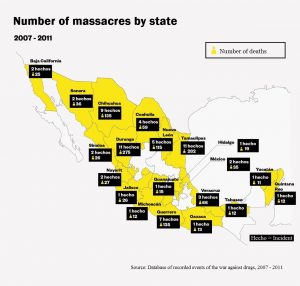

- Number of massacress by state