ARTICLE: We Want Us Alive

25/08/2016

LATEST: Social Unrest in Southern Mexico

25/08/2016“Education is an act of love, therefore, an act of courage.”

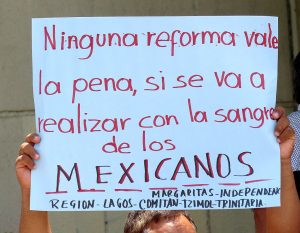

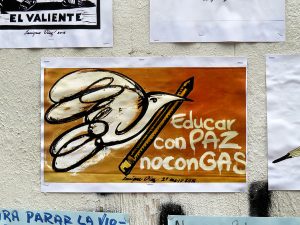

View of the “Barricade of words” that was installed in San Cristobal de Las Casas to express solidarity with the teachers’ movement © SIPAZ

In recent months, protests against the education reform have gained strength in many parts of the country, especially in the states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Michoacan. Since May 15 -a symbolic date, as it is Teachers’ Day- Section 7 of the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE) in Chiapas joined the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE), spearheading the teachers’ movement, to begin an indefinite labor strike. Joining forces in demanding a negotiating table with the Ministry of the Interior (Segob) and the Ministry of Public Education (SEP), the SNTE and CNTE entered an impasse given that, at first, both governmental bodies remained firm in their rejection of a dialogue. This is how entire schools were closed two months before the end of the school year across the country, leaving millions of children and young people without classes. Students, mothers and fathers, social organizations, small farmers, and people from the civil society joined the teachers who oppose the education reform. In Chiapas, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) announced in early July its decision to suspend its participation in the CompArte festival as a sign of “solidarity, respect, and admiration” to the teachers. This way, as material support, the five Caracoles delivered all the food they had initially intended to use during the festival to teachers in resistance, which amounted to about MXN$ 290,000.

As external support for the teachers’ movement was increasing, repression by police forces intensified in return. On June 19, nine people were killed, more than a hundred were injured, and 18 were detained in a roadblock in Nochixtlán, Oaxaca. This blockade, in support of the teachers’ struggle and as an impediment to the arrival of police who could dismantle the teachers’ encampment in the capital through use of violence, was ambushed by members of the gendarmerie and of state and federal police who were carrying weapons. Desinformémonos considered that these facts show “the serious democratic setback that Mexico is living, where a civil protest is met with the use of heavy caliber firearms despite them being banned to discourage any social protest in international protocols.” According to La Jornada, a week after the deaths in Nochixtlán, Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN) was greeted with shouts of “Murderer!” within the framework of the North American Leaders’ Summit in Quebec, Canada. However, he did not hesitate to lash out against the dissident teachers. First he said: “It is unfortunate that the demonstrations we have seen in different parts of our country, […] specifically in the state of Oaxaca […] that go beyond simply fighting for a cause […] are causing problems to the community to which they belong”, before reaffirming his rejection of dialogue: “There will be no dialogue with teachers on education reform.” The next day EPN again disparaged the teachers opposed to education reform, urging them to “carry out their social function (sic.)”. The Canadian president, Justin Trudeau, who was a teacher, reacted to that call by inviting his Mexican counterpart to engage in “constructive dialogue and ensure the strengthening of the rule of law.”

But why this level of repression of the demonstrations? Where do protests come from? What are their objectives? Who are they composed of? In what is to come, we will review some issues to try to answer these questions.

The Education Reform

In 2013, the President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto – from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) – presented a package of reforms to the Constitution, the so-called “Pact for Mexico” -an agreement between the main political parties to promote economic growth and the construction of a society of rights with justice, security, transparency, and free from corruption, which resulted in the approval of reforms such as those to energy or the Internal Revenue (IRS). While the first did not lead to the expected economic growth, the second did not provide the promised fiscal stability. Moreover, three years after its approval, Mexico increased the number of people living in poverty by 2 million, according to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL).

The education reform was also included among this set of reforms. Approved in the short term of just twelve days, it produced signs of rejection from the beginning. One of the innovations that it proposed was autonomy in the management of schools. “With this term the government expects that parents will have the responsibility of addressing the administrative problems of schools, which have always been a governmental obligation, such as payment for electricity and water, breakdowns and materials,” according to Imágenes Múltiples. Analysts have pointed to this reform as the beginning of the privatization of education, to cease being public and free. As the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) pointed out in a joint statement, “Those who delight in power decided that education, health, indigenous and campesino territories, and even peace and security are a commodity for whoever can pay for them, that rights are not rights but rather products and services to be snatched away, and they dispossess, destroy, and negotiate according to what big capital dictates”.

Teacher Evaluation

Pilgrimage of the Believing People in solidarity with the teachers’ movement in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas © SIPAZ

Another point that caused widespread opposition has been the performance evaluation. By means of an examination of teachers, which will be held at least every four years, the government intends to measure the adequacy of their educational practice, regardless of their academic level, experience, the human quality of the treatment of students, and also ignoring the cultural and socioeconomic differences that exist in the country.

Wide sectors understood this evaluation as a way of selecting teachers. This exam would end the labor stability of education professionals on the pretext of only keeping the “apt’ teachers. Hugo Aboites, Rector of the Autonomous University of Mexico City (UACM), said on the same note: “They clearly opted for an evaluation to find culprits, to search for those unsuitable and somehow get them out of the classroom.” The reform stipulates that non-approval of a third evaluation involves relocation or removal from office without the teacher being able to appeal. Although the Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN) recognized the right of teachers to administratively and judicially challenge adverse outcomes, the challenge can only refer to the syntax of evaluation questions. In this way, the lack of right to review or replication fuels the discontent and distrust of teachers to an evaluation that they consider “punitive”. Who will qualify them and under what criteria?

That is why this reform is increasingly known as “the badly-called education reform” and increasingly understood as a labor reform. In the communiqué FROM WITHIN THE STORM, the EZLN and the CNI repudiated the imposition of “the neoliberal capitalist reform, supposedly about “education,””, which comes with “violence used to dispossess [the teachers] of their basic work benefits “. “When one reads it, one realizes that it does not say anything about education in Mexico at all,” the cartoonist and writer Rius said, “it is only a labor administrative reform, and it aims to bring teachers’ unions to heel.” The education reform “tramples our labor protections that were achieved precisely with the union struggles of the 70s, when the CNTE was created,” said one teacher in Chiapas.

The Fight Against Trade Unions

The National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE) is an alternative trade union organization of teachers to the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE). The CNTE was created in 1979 in Chiapas, precisely in the southeast of the country, where the teachers’ movement is stronger, “with intentions of democratizing their own union,” according to La Jornada. It has historically affiliated teaching sectors that differ from the policies of SNTE, known for having corrupt practices and ties to the government, despite being a union independently.

According to statements in the Program “Aristegui Noticias CNN”, sociologist Gilberto Guevara, author of Power for the Teacher, Power for the School, recalled that “2008 is the apogee of power of Elba Esther Gordillo and the SNTE, because those who governed, in this case Felipe Calderon who was president, handed the management of national education to the SNTE in exchange for the electoral functions of the union “.

The Mobilizations

Pilgrimage of the Believing People in solidarity with the teachers’ movement in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas © SIPAZ

Since the approval of the education reform in February 2013, the opposing teachers have expressed their dissatisfaction through hundreds of protests ranging from traditional marches, sit-ins, road blockades and labor strikes, to artistic and cultural events such as cultural barricades with films projections and the installation of newspaper murals. At the end of this report, the teachers remained on an indefinite strike, which began on May 15 of this year, demanding the repeal of the education reform

Many of the demonstrations have had police force interventions, the most brutal example of repression being in Nochixtlan, Oaxaca. Although the Secretary of State for Public Security, Jorge Ruiz, stated that the security forces “came to evict them [the protesters], in a peaceful way and agreed with the leaders of those who remained in this blockade” eyewitnesses interviewed by Animal Político, asserted that there were beatings from the police and tear gas from the outset. “They [the police] did not speak […] they came throwing bombs and we [the protesters] ran but they followed us,” even attacking pedestrians who did not participate in the protests, but were only passing through. Moreover, after the death of several people from the civil society from gunshot wounds, the head of the Federal Police, Enrique Galindo, denied that those in uniform who participated in the operation in Nochixtlan were carrying weapons, even to launch tear gas canisters, but only wore“riot gear: shield, helmet, body armor, no weapons.” However, as officials involved in the national security cabinet revealed to La Jornada newspaper (03/07/2016), about 100 gendarmerie officers arrived armed, disobeying the decision taken in the capital of the country. In late June, the decision was taken to establish the facts in Nochixtlan and pay damages done to the families of the deceased.

Prior to Nochixtlan, police operations claimed the lives of three teachers in protests, one of those in Chiapas and two in the state of Guerrero. The three cases had similar media coverage: officials denied the participation of the armed forces in the deaths, while teachers and pointed directly to the security forces as being responsible.

Criminalization of Social Protest

Pilgrimage of the Believing People in solidarity with the teachers’ movement in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas © SIPAZ

For months a smear campaign has been conducted against the teachers’ movement in many media outlets. With arguments such as them abandoning girls and boys during the strike, that their struggle is only based on hollow complaints and do not provide concrete proposals to improve education, teachers in protest have been called “lazy, vandals, privileged” among other insults. “We have seen some teachers, the minority, in open rebellion. And teachers as examples of violence, irresponsibility, even impunity […] How do we confront those Mexicans who do not build the Mexico I need?” or “in some states like Chiapas, like Oaxaca, education is held to ransom […] it cannot be that these individuals give class in the classroom. What kind of education are they giving to children?” are just some examples of sound bites that can be heard on different radio stations.

In late May, social organizations and teachers symbolically occupied dozens of town halls for several hours, in Chiapas more than half of them. In Comitán, an event attracted the media coverage of the day, six teachers had their heads shaved and forced to walk barefoot carrying signs with slogans like “traitors to the homeland” and “charros”. Most of the press claimed the CNTE was responsible for this public humiliation, although it was carried out by the Emiliano Zapata Independent Popular Organization (OPIEZ in its Spanish acronym), a social organization made up mostly of street vendors. As Luis Hernandez Navarro pointed out, “one of the most active offenders is, curiously, one of the biggest operators of the mayor”, and OPIEZ “operates in the municipality as the clash groups of the mayor.” The writer and journalist branded this coverage as a “nationwide media attack” in order to “falsely accuse the democratic teachers of the offense.” It noted that this was not the first national media campaign, that eleven months ago a supposed teacher had publicly had his head shaved in Tuxtla Gutierrez was discovered to be a federal agent. These reports are “manipulated by the government, when they say teachers shave heads, teachers run over [people], they are disturbing society,” a CNTE teacher in Chiapas declared. “We know that they handle infiltrators, that they are people paid by the government precisely to discredit the movement we are creating.”

Pilgrimage of the Believing People in solidarity with the teachers’ movement in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas © SIPAZ

Opposition to the evaluation has also been the subject of defamation in the media. Presented as a fear of instructors of being evaluated, “is very simplistic,” said one teacher in Chiapas. “We are seeing our work situation being fraudulently affected.”

Beyond the media campaign, in Oaxaca, the CNTE reported that during the tenure of the current governor, Gabino Cué Monteagudo -from the coalition United for Peace and Progress- there are more than 75 political prisoners, of whom at least 25 are dissident teachers. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention considered that several arrests were directed against human rights defenders and were carried out in arbitrary conditions. Among the arrests, those of Ginés Ruben Nunez, secretary general of Section 22 of the Oaxacan teachers, and Francisco Villalobos, secretary of organization of the same section stood out. Both were arrested in early June and transferred to the Federal Center for Social Rehabilitation in Hermosillo, Sonora, nearly 2,500 kilometers away from their hometowns. The first was charged with laundering more than 24 million pesos in backhanders from companies providing services to the union, while the latter was accused of stealing textbooks for free distribution from the Ministry of Public Education (SEP). In response, the lawyer Magdalena Gomez said that “what matters is suppressing social protest” for the current the federal government, “it knows that there are many mobilized fronts and prefers to sow fear” instead of “processing the conflicts with the logic of democratic governance.”

Besides these two teachers’ leaders, at least 24 more face arrest warrants. And this only in the state of Oaxaca. Various United Nations rapporteurs issued “urgent calls to the Mexican authorities” over human rights violations, mainly over arrests without warrants or search warrants and the use of torture in the moments following the arrests.

Solution to the Conflict?

Mural during the cultural event that took place on June 26 in San Cristobal de Las Casas for 21 months of the disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa © SIPAZ

Protests by the educators do not seem to be waning. Moreover, in the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca they are gaining more and more sympathy and support from the civil society. Many people understand that the teachers’ struggle not only seeks to maintain their labor rights but also that the demand for the repeal of the education reform “also affects all citizens, among other things because it threatens free education,” the illustrator Helguera said. After the deaths in Nochixtlán and pressure both domestically and internationally, the government had no other option than to establish the negotiating table requested by the CNTE from the outset and which the authorities had repeatedly opposed. At the end of this report, the installation of a negotiating table between the Secretary of the Interior, Miguel Angel Osorio Chong and a representative of the CNTE was achieved. A first general agreement was reached in which three parallel negotiating tables will be installed. Political, educational and social tables will be held in late July. Also, the CNTE noted that they will maintain their action plan and the demand that the claims raised before the federal agency are met, which would be the “permanent suspension of the reform, construction of an integrated model of education and immediate reparations for the harmful effects of reform.”

As an organization of international accompaniment, as SIPAZ we call for a resolution to the teachers’ opposition through dialogue, avoiding that both teachers and civil society have to go through violent acts that leave tolls of injuries or even deaths.