LATEST: Mexico, Continued Insecurity

27/09/2023

ARTICLE: Spinning Alternatives with Children and Adolescents in Chiapas

27/09/2023Nobody leaves their home, unless home is the mouth of a shark.

You only run towards the border when you see that the whole city does too.

Your neighbors running faster than you. With breath of blood in their throats.

The boy you went to school with (…) holds a gun bigger than his body.

You only leave your home when your home does not allow you to stay (…)

Violence and Climate Change, the Main Threats

E very June 20th, World Refugee Day is celebrated, in a context in which, according to data provided by the United Nations (UN), twenty-four individuals leave their homes every minute, escaping war conflicts, persecutions or horror situations. Currently, it is estimated that more than 110 million people in the world are are in situations of forced displacement, both inside and outside their countries of origin.

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), “the majority of people forced to flee never cross an international border, but rather remain in its own country. These people are known as internally displaced people, who represent 58% of the total number of people displaced by force.”

The number of people displaced against their will has grown globally due to violence caused by recent or ongoing conflicts, as well as catastrophic natural events, among other factors, which are linked to climate change.

The Action Agenda of the Secretary General of the United Nations mentions: “The urgency of preventing internal displacement and finding solutions is particularly serious in light of climate change, which is not only a factor of displacement, but also a multiplier of risks. The World Bank estimates that 216 million people could be forced to move internally by 2050 in only six regions due to climate change if no action is taken immediately.”

In Mexico “there is no problem”

According to data from the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights (CMDPDH), in 2021, 42 displacement cases were recorded with 28,943 people affected. This investigation details the displacement cases of at least nine states of the country.

For its part, a report from the Internal Displacement Observatory (IDMC) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) documented that, in 2022, in Mexico, the vast majority of cases of forced internal displacement (IFD) were due to the violence that prevails in the country (386 thousand versus 3,600 people due to disasters). This through 9,200 forced movements.

They also reported that the number of internally displaced people in Mexico has risen steadily during the past decade and that in many cases families returning to their homes must leave them again due to lack of security. According to the latest data from the Observatory, Mexico is the country that occupies first place among nations that, without officially being at war, has most victims of displacement in the world, it is estimated that, today, there are between 350,000 and 400,000 internally displaced people throughout the territory.

In the International Spotlight

In January of this year, the LVI National Congress on “Indigenous and Afro-descendant Peoples and Communities” was held in the city of Oaxaca, in which the UN representative in Mexico, Guillermo Fernandez Maldonado Castro, gave a keynote speech on Forced Internal Displacement Affairs in Mexico during which he spoke about figures, legislation and trends of this problem: “Today Mexico still does not have national legislation, official national figures or disaggregated information, essential to know the magnitude and evolution of the internal displacement in the country, as well as the different profiles and geolocation of people displaced”, he stated.

Months before, between August and September 2022, the former UN Special Rapporteur on human rights of internally displaced persons, Cecilia Jimenez-Damary, visited the states of Chihuahua, Guerrero and Chiapas, where she met with government officials, human rights organizations and civil society. At the end of her visit, back in Mexico City, she held a conference where she detailed what she had observed and some of the data collected during those days: “I have observed that, in Mexico, the causes of displacement are diverse and multifactorial and require comprehensive care, including the adoption of prevention, care and protection measures for displaced people with a human rights, differentiated and intersectional approach and achieving conditions for lasting solutions”, she declared.

Later, in the report resulting from her visit presented by her successor Paula Gaviria Betancur in June of this year, she also mentioned that Mexico has high rates of violence and she pointed out that, during the mission, she listened to victims of organized crime and observed how “criminal groups terrorize and control territories and populations through threats, intimidation and violence.” She observed that, “despite the high rates of violence, few people dare to report, for fear of being subject to reprisals or lack of trust in the authorities, and particularly in the criminal justice system.” Likewise, she highlighted that, “in the cases in which there were complaints, the people interviewed stated that the competent authorities closed the investigation files or the investigations were not concluded, even in serious crimes such as homicides and disappearances. Added to this feeling of impunity is the perception of corruption at all levels of government.”

On another note, she made special mention of the situation of indigenous peoples and pointed out that “they have historically suffered structural inequalities, exclusion and systematic violence. Obstacles persist that prevent them from fully enjoying their human rights, such as extreme poverty; violence by armed actors, including organized crime groups; lack of recognition of regulatory systems and their own institutions; the progressive hoarding and appropriation of their lands, and the design and implementation of investment projects by the State and private companies.” She also expressed her concern about what representatives of these peoples and civil society organizations described “cases of internal displacement issues linked to disappearances, sexual violence, gender-based violence, femicides, homicides, massacres, recruitment, forced labor or extortion, among others.”

She pointed out that “in the framework of these conflicts, in addition to serious impacts on human rights as a result of forced disappearances, land grabs, environmental and social impacts, attacks and criminalization of indigenous leaders, have generated internal displacements of communities and indigenous peoples.”

The Special Rapporteur also confirmed the internal displacement caused by development plans and projects related to mining, logging, hydrocarbon extraction, construction of dams and tourism, including the Maya Train. In this sense, she observed with concern the irregularities and harassment that indigenous communities face to express their free, prior and informed consent.

It should be noted that, although indigenous peoples and communities represent ten percent of Mexico’s total population, more than 40 percent of recorded displacement episodes by civil society in 2020 affected these peoples. The states with the greatest number of indigenous internally displaced persons are Chiapas, Chihuahua, Guerrero and Oaxaca.

Finally, the rapporteur left some recommendations for the Mexican State, among which the need to create a law that protects internally displaced persons stands out, as well as a federal registry of victims of internal displacement: “While it is necessary to create a single federal registry of internally displaced persons, in addition to the records at the state level, this must not only include those who have been legally recognized, but also those who do not have that legal recognition, but are de facto displaced. Registration should not confer legal status, but should have the purpose of facilitating protection and humanitarian assistance in accordance with the individual and collective needs of internally displaced people”, she stated.

The Case of Chiapas: From Internal Conflicts to Turf Wars

In Chiapas, the problem of forced displacement is not new, and until recently, it was not mostly associated with organized crime. Internal displacement due to political and religious issues in the municipality of Chamula (1960- 1980), by the hydroelectric project in Chicoasen (1980) and by natural disasters, such as the eruption of the Chichonal volcano (1982) or Hurricane Stan (2005) in the coastal area, have not been forgotten. Displacements since the nineties linked to issues of socio-political violence, especially among the indigenous population in the Highlands Region and the northern part of the state, where massive displacements occurred in the years following the uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) due to the strategies of the federal government to combat the revolutionaries and the emergence of armed groups and paramilitaries who unleashed a harsh wave of violence.

However, in recent years and increasingly, FID can be linked to the turf wars between organized crime groups. This is how we were able to observe it in the case of Frontera Comalapa at the end of last May, where there was talk of at least three thousand displaced people, a figure that equals the episode that recently had the largest number of people affected, that of Pantelho, where around 3,205 Tsotsil and Tseltal indigenous people had to be displaced due to clashes between armed groups.

At the national level, Chiapas is the second most affected state in terms of FID. There is no data on the exact number of people that have been displaced by violence, however, in an investigation by the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba) it is estimated that, between 2010 and 2022, at least 16,775 people have left their homes due to insecurity. Of this, at least 4,634 were displaced during 2022. As of today, the figures are not clear, but could rise exponentially. The most affected municipalities have been Aldama, Chapultenango, Chenalho, Ocosingo, Pantelho, Venustiano Carranza and recently Frontera Comalapa and La Trinitaria.

Although Chiapas has a Law for the Prevention and Assistance of Internal Displacement in the State, the institutions’ capacity to react to so many events of displacement is very limited and does not guarantee that there can be real attention to the people in this situation or the causes that generated it.

Guerrero: Between Terror and Struggle

According to La Montaña Tlachinollan Human Rights Center, forced displacement in Guerrero, which today affects more than 26,700 people, is caused by “a model of criminal economy that has been established in the state with illicit businesses in which criminal groups are used for control; disputes over forests and mining projects, as well as the violence linked to drug trafficking, which seeks to take over territories and routes for the transfer of drugs.” It mentions that in recent years there has been a silent displacement of thousands of people, mainly in Tierra Caliente, the Sierra, the Costa Grande and the northern, central and La Montaña regions.

For its part, the Jose María Morelos y Pavon Center for the Defense of Human Rights points out that in Guerrero there are no guarantees for displaced people: “the State is incapable of guaranteeing human rights to the displaced, since since September 2020 the Chamber of Deputies unanimously approved the General Law on Forced Displacement, which was sent to the Senate of the Republic where it remains in the freezer.”

It should be noted that in May 2022, the first national meeting of the displaced, where victims of forced displacement from Chiapas, Guerrero, Chihuahua, Michoacan, Quintana Roo and Mexico City participated, was held in Chilpancingo. This meeting was an opportunity for the different groups to reach various agreements, among them that of uniting their demands for the Mexican State to guarantee material and psychological stability for women, girls and boys who are victims of forced displacement.

They also mentioned the importance of addressing the deepest causes of forced displacement and outline a work plan for this year that integrates several lines of strengthening and highlighting. During the event, they called on human rights organizations and groups to stay united and group others who want to join the movement, with the intention of giving greater visibility to the problem of forced internal displacement and achieving a higher level of impact on the authorities.

The Danger of Reporting and Defending Rights in Mexico

The risks faced by human rights defenders and journalists, as well as their displacement as a result of threats, assaults, criminalization and other attacks, have been subjected of concern of different experts at the international level. Proof of this is the report presented on July 11th by the CSO Space for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, made up of various organizations that work on issues of defense of human rights.

In the document titled “People and Communities Defending Human Rights and Journalists in a Situation of Forced Internal Displacement in Mexico”, show the reality that the human rights defenders and journalists in situations of forced internal displacement, which, they point out, becomes more acute when it occurs among groups of people who suffer from other historical and structural vulnerabilities.

In the section “Violence and Limitations for the Exercise of the Right to Defend Human Rights and Freedom of Expression in Mexico”, they point out, among other things, how, “in addition to attacks on their lives, defenders and journalists face campaigns of discrediting, acts of intimidation and harassment, threats, physical and digital attacks, arbitrary detentions, use of the justice system against them, disappearance and forced internal displacement.”

They emphasize in their report that “In the case of human rights defenders and journalists, they are increasingly forced to leave their place of origin or residence in order to safeguard their life as a result of the climate of hostility, threats and attacks to which they have been subjected, as well as the absence of effective measures of prevention, protection and delivery of justice, turning internal forced displacement into a survival resource.”

The document mentions that “there are no official sources that allow us to diagnose in a comprehensive and specialized way the nature and magnitude of the problem at national level, much less have specific instruments that offer exact figures on the number of human rights defenders and journalists who would have had to move from their places of origin or habitual residence in a forced manner” but that the number of beneficiaries of the Protection Mechanism of the Ministry of the Interior could offer some clues. According to the report, as of January 2023, the Protection Mechanism has 2,059 beneficiaries, of of which 581 are journalists: 152 women and 428 men; and, 1,099 are defenders: 609 women and 490 men. “Despite the scarcity of information, the data allow us to show the upward trend of the phenomenon and recognize that both groups face a particular situation of vulnerability, since their work exposes them to a high level of violence”, they conclude.

The Devastating Impact of Displacement

A large majority of victims of displacement have stated that it always comes accompanied by the loss of livelihood, there is also a loss of social and cultural identity, in particular, for indigenous peoples, who have a special attachment to their ancestral lands and customs. Family disintegration and psycho-emotional effects, fear and hopelessness are also a constant. In the case of journalists and defenders, the consequences and impacts of displacement also include the violation of their right to exercise freedom of expression and defend human rights.

Highlighting the situation of people in forced displacement is of vital importance to understand the causes and impacts that this has and avoid stigmatization, revictimization and criminalization of those who suffer from it.

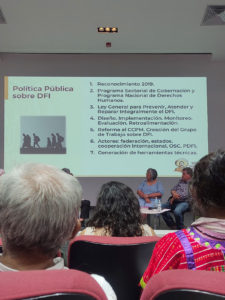

Recognition and Comprehensive Care

Recently, various international organizations and civil society organizations have expressed their concern to the government of Mexico about the internal displacement crisis that crosses the country, they have indicated that one of the great challenges is the recognition of the problem and the victims, as they point out, the seriousness of it has been minimized and even denied and this makes it impossible to generate appropriate action routes.

They agree that the State is primarily responsible for the protection and well-being of displacement victims and must address their particular situation of vulnerability. They emphasize the importance of promoting the creation and approval of comprehensive strategies, laws and public policies (prevention, protection, investigation, sanction and reparation with a gender, multicultural, age and a differential approach) that shed light on this serious crisis.