LATEST: Extreme Vulnerability of Defenders and Journalists in Mexico

03/03/2022

ARTICLE: Friar Gonzalo Ituarte Verduzco receives Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Medal

03/03/2022“The state of Guerrero combines a multiplicity of antagonistic and complex conflicts that are added to and intertwined with a series of historical structural flaws, such as social inequality and the consequent violence that has increased in recent years.”

T he twenty-seventh report on the activities of the La Montaña Tlachinollan Human Rights Center, Your Name that I Never Forget, presents the scenario in which a human rights crisis is developing that has kept the wounds of the Guerrero population open for decades. A crossroads of violence in which various sectors of the population live, particularly the indigenous.

No Man’s Land, Intersecting Violence

The state of Guerrero has a strategic geography. Its borders with Puebla, Mexico State and in particular Morelos, give it access to the center of the country; The Tierra Caliente region is characterized by its agrobusiness and livestock wealth, but also for being a strategic route for the transfer of drugs and the sale of weapons: an area of dispute for rival groups from Guerrero and Michoacan.

Chilpancingo, being the political center, is the place where the interests of those who decide on the seven regions of the state converge. It is the “necessary step” for people who travel from the northern area of Guerrero to the port of Acapulco. This has given criminal groups control of the routes that wind and fork towards the communities of the Sierra to which they have subjugated.

Acapulco boasts great economic power that contrasts with the misery belt on the outskirts: extreme poverty, unemployment, crime and a political power that has widened the inequality gap. For many, Acapulco is “the cemetery of the forgotten.”

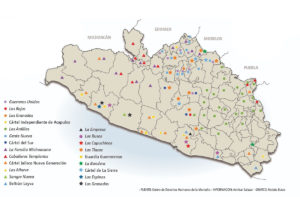

According to Tlachinollan, at least 22 organized crime groups are vying for the state of Guerrero. They are not only dedicated to cultivating and moving drugs, but also control the exploitation of natural resources in collusion with mining companies; they control formal and informal businesses in various regions and even “govern” municipalities, forcing the population to abide by their decisions. It mentions that, despite the militarization of the state, neither the National Guard nor the Army enter these areas.

According to data from the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP) in the state of Guerrero 1,200 murders were recorded during the first nine months of 2021, with the port of Acapulco heading the list of the five most violent of the state.

“The geographical location of the state has been strategic since ancient times to be taken advantage of by different organized crime groups, which currently operate alongside and often in collusion with public institutions, which have used these criminal groups as a private army to guarantee their impunity”, the Tlachinollan report points out.

Ayotzinapa, “The Justice that Distances Itself”

State police confront the students of the Normal of Ayotzinapa with stones, bombs and blows © Tlachinollan

In this context, the levels of violence and human rights violations in the state are not surprising, one of the most emblematic cases being that of Ayotzinapa. September 26th, 2021, marked seven years since the disappearance of the student teachers and their relatives marched in Mexico City where dozens of contingents endorsed their support and solidarity for the movement. In turn, Tania Reneaum, executive secretary of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), expressed her recognition and admiration for “keeping this demand alive in a country that soon forgets.”

In this long journey of the fathers and mothers, the IACHR welcomed the establishment of a dialogue with the President of the Republic and the creation of the Special Investigation and Litigation Unit for the Ayotzinapa Case and the Commission for Truth and Access to Justice decreed by the federal government in 2018. Without a doubt, these are advances of the current government that contrast with the stagnation of the searches during the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto. The location of the remains of Cristian Alfonso Rodriguez Telumbre in July 2020 and Jhosvani Guerrero de la Cruz in June 2021 are added to this, with which the “historical truth” fabricated by the then Attorney General’s Office (PGR) was rejected.

The fathers and mothers of the 43 recognized the work carried out by both the Special Prosecutor’s Office and the Presidential Commission chaired by the Undersecretary for Human Rights, Population and Migration Alejandro Encinas, and the independent experts. However, for them it is imperative to break the pact of silence that covers up the participation of the Army in these disappearances because there are data that indicate that different security forces, including the Army, were involved in this massive aggression, as they describe in the report. They believe that there should be no further delay in issuing the 40 arrest warrants pending for several months, nor in the extradition of Tomas Zeron de Lucio, former head of the Criminal Investigation Agency, who led the initial investigation into the disappearance of the student teachers and who is accused of torture.

It seems that justice is distancing itself for Ayotzinapa, dragged out by what analysts consider “a pact of impunity.” Despite the initiatives of the federal government to protect witnesses who give information about the whereabouts of the young people, “no one wants to talk”, the relatives complain. In a Mexico that ranks 60th out of 69 countries evaluated in the Global Impunity Index, and in a state where 96.1% of reported crimes go unpunished, the government continues to owe the entire country the truth about the events that occurred “that bitter night.”

Forced Disappearance: An Omnipresent Historical Phenomenon in the State

Forced disappearance in the state of Guerrero has been omnipresent since what is known as “The Dirty War.” According to the Tlachinollan report, during this period, relatives have documented more than 600 people disappeared. The “Death Flights” threw the bodies into the sea, staining the Pacific Ocean with blood along with the disappearances and murders carried out by the army, the navy and the state police corporations.

“The repression exerted against 800 coconut farmers, on August 20th, 1967, by the army, together with state police and Governor Raymundo Abarca’s gunmen, left a balance of 35 people killed and 150 injured”, Tlachinollan recalls.

The National Search Commission showed in its latest report that from March 15th, 1994, to November 7th, 2021, 98,008 people were declared missing nationwide, while in Guerrero, this figure reaches 3,719 cases.

For its part, the State Commission for the Search for Persons registered 175 missing persons in the first half of 2021, of which 48 were registered in Acapulco and 39 in Chilpancingo. According to the Other Disappeared Collective (Colectivo Los otros Desaparecidos) in Iguala, from November 2014 to mid-June 2021, 243 human bones and fragments have been found in various points on the outskirts of that city. During this time they managed to identify 68 people and 52 of them were handed over to their families.

One of the most recent cases is that of Vicente Suastegui Muñoz, who was deprived of his liberty by three armed men on his way back home on August 5th, 2021. The disappearance of the land defender and member of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP) is framed within the decomposition of the police bodies and “this climate of criminal violence that murders and disappears people they classify as enemies, without the authorities carrying out exhaustive investigations to arrest the perpetrators”, stressed Tlachinollan.

In 2017, the General Law on the Matter of Forced Disappearance of Persons, Disappearance Committed by Private Parties was adopted in the same way as the National Search System for Persons thanks to the shared effort between civil groups and organizations. Although this represents a triumph in regulatory matters, four years after its approval institutional barriers continue to be a challenge to be overcome. The authorities are indifferent to and distant from the victims; they make judgments without knowing the causes of this growing phenomenon. For Tlachinollan, “the search for disappeared persons represents irreparable damage to the families”, they are stigmatized and blamed such that the authorities justify disclaiming responsibility for accompanying and supporting them.

Marco Antonio Suastegui, leader of the CECOP, undertook the search for his brother, Vicente, due to the lack of implementation of a protocol by the authorities. Like many other relatives of the disappeared, Marco Antonio has put his life at risk by having to search on his behalf in highly insecure areas.

A Region of Silence for Environmental Defenders and Journalists

“The disappearance of Vicente is an example that in Mexico there is a crisis of insecurity to preserve the lives of defenders”, states La Montaña Human Rights Center in its report. The document also mentions that the state of Guerrero ranks fourth nationally in the number of attacks against human rights defenders and journalists, a region of silence where “media coverage is not given or avoided, due to the imminent risk that implies accounting for the insecurity, impunity and injustice that prevail.”

The crisis in which the right to free expression finds itself in Mexico is a reflection of what is happening at the local level. In Guerrero, journalists are also victims of municipal authorities who criticize, delegitimize and criminalize them. One case is that of the municipal president of Tlapa de Comonfort who dismissed the work of the journalist Carmen Benitez Garcia and the defender Neil Arias Vitina. These attacks against them occurred a few months before the forced disappearance of defender Arnulfo Ceron Soriano, on October 11th, 2019, who also suffered a campaign of delegitimization and criminalization by the same official.

“The attacks on human rights defenders and journalists are not an unusual practice, but, on the contrary, part of a state malpractice that is evident at the different levels of government, as exemplified by the statements of the President of the Republic Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who continually disqualifies the defense work and discredits the consequences of risk to which they are exposed, sending a message of permissibility and impunity to the aggressors”, the report states.

Tlachinollan presents the cases of murdered human rights defenders that they have documented between September 2020 and August 2021 in the report. The first was the environmentalist leader of the Los Guajes ejido, Elias Gallegos Coria, and his son, Fredy Gallegos; the last one, that of Guerrero journalist Pablo Morrugares and his bodyguard, this despite the fact that he had been a beneficiary of the Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists since 2016. They also highlighted the case of the Jose Maria Morelos y Pavon Regional Center for the Defense of Human Rights whose members suffered different attacks by organized crime and local authorities for their work accompanying the communities victims of forced displacement.

“There are many pending issues, but even in the darkness of this forgotten Mountain, we know that the demands are legitimate, that our work is peaceful and above all necessary, so the right to defend human rights and the right to information should not cost life, but on the contrary, it is the authorities that must guarantee that our work is carried out in conditions of safety and freedom”, Tlachinollan points out in its report.

“Displace to Rule”

According to the latest report of the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights, in 2020 the victims of forced displacement at the national level rose to 9,741, of which 3,952 are concentrated in Guerrero. However, there is still no official census and the Senate has been paralyzing the Federal Law on Forced Displacement for more than a year. In addition, “as it is not classified as a crime in the federal or state codes, the victims are defenseless”, said the Jose Maria Morelos y Pavón Regional Human Rights Center.

The new lines of business in which criminal groups are entering are another cause of this phenomenon. Conflicts with extractivist companies have been aggravated by the influence of criminal groups that are in charge of terrorizing communities by assassinating heads of families to displace their widows and children, seize the forests or rivers that the communities protect.

Entrepreneurs have made use of these criminal organizations and the support of federal officials responsible for protecting the environment and state and municipal authorities who join forces to conduct business under the protection of power and continue with the looting of natural resources. During the online forum Latin American Experiences of Forced Displacement and Prevention Measures, Tlachinollan mentioned that the control of organized crime, together with authorities, private companies and the public force “systematically transgresses human rights without any consequence” and “gives a glimpse of how state players and criminal groups operate in a mining region, where the owners of the land have to bow to the macroeconomic interests of transnational companies.”

In the Sierra region, the cultivation and movement of drugs aroused the greed of criminal groups that have displaced dozens of families to take control of the routes. In other areas such as the Center, North, Tierra Caliente, Acapulco and Costa Grande there are also cases of internal forced displacement.

The state government has only partially complied with the demands for housing and the construction of a school, leaving aside the issue of security and the dismantling of the armed groups that patrol their communities and are part of organized crime. In addition, displaced people suffer from medical neglect in times of pandemic, they do not have access to medicines and when a family member dies and they want to return to their community to bury them, it is the criminal group that controls the municipal capital who decides whether they can enter or not. This shows that the chances of return are close to zero.

Femicidal Violence, Executioner of Guerrero Women

According to official figures from the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System, of the 626 femicides registered in Mexico in 2020, ten occurred in Guerrero; 91 intentional homicides of women; 1,925 cases of family violence; 214 case reports of alleged crimes of rape; as well as 4,262 emergency calls related to incidents of violence against women.

From September 2020 to October 2021, they documented 26 femicides in different municipalities of the state. According to the follow-up that the Center has given, in only 20% of the cases have those responsible been prosecuted and a minimum percentage has reached convictions.

The victims of gender violence in the state are many, but they are, above all, girls. When forced marriages occur, the lives of girls are cruelly truncated “leaving disastrous messages within the indigenous communities: domination is exercised by men and the role of women is to subordinate themselves. Any dissent is paid for with life”, says the Tlachinollan report. For some, “the custom that existed before has been perverted, (…) Now everything is to be fixed with money. (…) Women are not merchandise, no matter how obedient and respectful we are of the customs of the people”, the testimony of a young woman in the report states. In many cases, the lack of close support networks and the remoteness of the communities in which the women live, empowers the perpetrators to commit these acts without witnesses to account for the facts.

Indigenous women are especially vulnerable due to the absence of institutions. There is an environment of normalized and dehumanized violence that is coupled with the ineffectiveness of the justice system that maintains these crimes in impunity. Despite the fact that, since June 2017, ten municipalities in Guerrero have had a Declaration of Gender Violence against Women (AVGM) and a second one for compared tort in June 2020, there have been no effective results to reverse this violence. The hundreds of cases of femicide violence show the indifference and inefficiency of the institutions. The investigation protocol for femicide is not applied, there are delays in investigations and discriminatory practices continue.

Guerrero, “Free and Sovereign” State

During the electoral contest in June 2021, the National Electoral Institute (INE) registered a total of 1,465,543 votes in the state of Guerrero, which represents a participation of 57.83% of the electorate. The candidate for the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), Evelyn Salgado Pineda, won the contest with a total of 643,814 votes. However, contrary to expectations, one hundred days after her inauguration, La Montaña Human Rights Center showed in its report that under the MORENA government “the institutions drag out the vices of corruption, continue with the practices of contempt and indifference to the population, the lack of dignified and truthful attention.”

The election of Evelyn Salgado took place on a stage where the backdrop was the map of violence and insecurity in Guerrero. In this scenario, organized crime groups are leading a struggle for control and territorial expansion while the authorities play the role of allies, Tlachinollan evidenced. Guerrero is one of the states where “the intervention of organized crime became more evident.” Through threats to the candidates and/or their families, the criminal groups forced them to desist from their intention to govern and in other cases, they supported and imposed a particular candidate, said Animal Politico.

For La Montaña Tlachinollan Human Rights Center, in addition to declaring a frontal fight against impunity, this government has the challenges of addressing the great legislative deficit in the state; care for victims of serious human rights violations; reverse poverty rates and institutional abandonment. For this, it is necessary to purge the institutions in charge of security and the administration of justice.

“The people of Guerrero have always been up for the fight and have never allowed themselves to be defeated in the face of so many atrocities, on the contrary, they are willing to fight at all times to free themselves from the chains of a political system that only uses their vote to elevate people who have betrayed and defrauded them. This new political configuration is to promote substantive changes that place the citizen at the center of political action”, the report mentions. Much of it aims to highlight their processes and commitments, their dignity and resilience.