LATEST: Mexico – “A long way to go to exit human rights crisis”, Government

18/03/2021

ARTICLE: Samuel Ruiz García – Ten Years of Living Memory

18/03/2021Of the 100 largest economies in the world, 51 are companies; only 49 are countries.

G lobalization in today’s world has resulted in changes at both the micro and macro levels, with pros and cons, including new challenges when it comes to the protection of human rights (HR). The globalized world has reshaped economic powers into a world in which multinational companies have especially come to gain unprecedented power and influence.

Businesses have an enormous impact on the lives of people and the communities in which they function, including positive impacts. However, human rights organizations and civil society, through various reports with countless examples, have shown situations in which companies take advantage of inefficient national regulations, which end up contributing to violating human rights and causing serious damage to the environment, without any consequences for those responsible[1].

Companies: the obligation to respect human rights

The obligation to protect and ensure that human rights are respected is the responsibility of the State[2]. However, in a world in which companies have more and more power, sometimes even more than states themselves, a complex situation is created. Businesses also have an obligation to respect human rights no matter in which country or where they are operating.

It should be clarified that the obligation to respect human rights is not the same as what is called Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) [3], of which a growing number of companies boast. In this field, they are allowed to choose what they want to do and what social responsibility they can assume depending on their good will, while, with human rights, you cannot choose which ones you want to comply with, something that concerns both companies and investors behind their projects.

Human Rights Defenders at Risk

“The responsibility of companies to respect human rights implies not only a negative duty to refrain from violating the rights of others, but also a positive obligation to support a safe and conducive environment for human rights defenders in the countries in which they operate.” – Michel Forst, former Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders for the UN.

It has been documented that defenders and communities that defend the environment, as well as the land and territory, are increasingly facing serious threats due to the strategies of some companies that try to silence them, which sometimes has even led to their death. The Business and Human Rights Resource Center highlights how prioritizing the commercial interests of companies often prevails over those of communities[4]. A legal term has even been coined for it: SLAPP, which stands for “Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation”, which describes a lawsuit filed by companies with the purpose of preventing a person or a group of people from speaking freely about certain things or exercise their rights[5].

Multiplication of international initiatives to protect human rights regarding companies

With the empowerment of companies, their responsibility for human rights has become a more relevant debate. During the last ten years, international initiatives have been presented with the aim of creating or improving effective mechanisms for the protection of human rights, both for the protection of victims and for the companies themselves.

In 2011, the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights was created which, among other tasks, makes official visits to the different States, the last one in Mexico being in 2016. In addition, after a six-year investigation, a normative framework was created the same year grouped in the “Guiding Principles of Business and Human Rights”, under three pillars: “Protect, Respect and Remedy.” It establishes 31 principles directed to States and companies, in which they clarify the duties and responsibilities of each with regard to the protection and respect of human rights in the context of business activities. It defines that States must not only protect the rights of citizens, but also that they must regulate the companies’ actions through laws and public policies, and when there is a violation of human rights by a company, they must ensure that redress mechanisms are implemented[6].

The European Union has been consolidating an initiative through what would be a binding “Due Diligence” * Treaty, the objective of which is to have a regional legal framework that requires European companies to integrate the issue of human rights, as well as the environmental due diligence in all its operations, and holding them responsible for their behavior in third countries[7]. It has been reported that the legislative initiative will be presented by the European Commission during the year 2021.

* Due diligence is the way in which a company understands, manages and communicates the risks involved in its operation (European Commission. 2020)

The lack of real openness of the Mexican government

In both Mexico and several other countries, the debate on Business and Human Rights is increasingly present on the agendas of different players, largely due to pressure from civil organizations working on the issue. For example, in March last year, several multilateral agencies and organizations, including the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) in Mexico, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the European Union and the Focus Group of Civil Society on Business and Human Rights in Mexico, organized a multi-sector forum to discuss the best way to implement due diligence, and explore alternatives to better protect people in vulnerable situations from possible corporate abuse.

Several Mexican governments have expressed openness to include civil society and communities affected by business projects in the development of public policies, however, so far, none has managed to open a truly participatory process. “Rather, it was a simulation process where the government meets with organizations and communities and reaches agreements, but in the end they are not fulfilled”, says Yvette Gonzalez, from the organization Project on Organization, Development, Education and Research (PODER), who participated in the working groups organized at the initiative of the government of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018).

Last December, the government of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador presented the National Human Rights Plan (PNDH in its Spanish acronym) that contains several important strategic lines towards promoting mandatory due diligence for companies in the country. They could be a major breakthrough. However, doubts remain that its implementation will become a reality.

Sustainable development for whom?

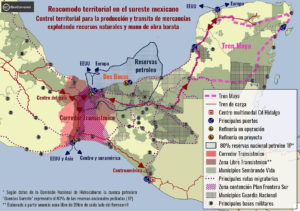

Despite the fact that the Mexican State has signed and ratified hundreds of human rights conventions, including on this issue, for decades, successive governments have promoted megaprojects and extraction as priority forms of development, many of these projects causing as much serious environmental damage as human rights violations of indigenous communities and the population in general. Several of them are implemented by public companies, making it difficult for the State to play a mediating role between the population and companies. Furthermore, with the energy reforms since the late 1980s, various sectors of the economy have been liberalized, which has facilitated the entry of transnational companies into the country.

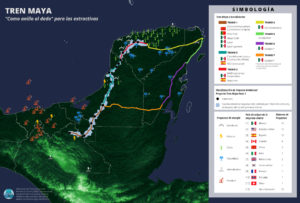

Currently, one of the flagship projects of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador is the Maya Train, which has not only raised strong questions about the environmental effects it would have, but also about the violations of the rights of the indigenous peoples affected, omitting several rights included in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) *. In addition, several investigations show that the main beneficiaries of the Maya Train project will be mainly large companies. However, this project and the questions it has raised are not an isolated case.

Ejido Carrizalillo, Guerrero

The Carrizalillo ejido in the state of Guerrero has one of the most important mines in Mexico for the production of gold and silver with two open pits and an underground mine. It has had a mining presence since 2008, then through the Canadian company, Goldcorp. From 2014 to the present day, it is exploited by the mining company Leagold Mining Corporation merged with Equinox Gold, also with Canadian capital.

Over the years, the ejido that had initially managed to negotiate various compensations with the company has experienced dispossession, environmental contamination and damage to health, as well as lack of compliance by the company with the agreements signed. In addition, there have been actions of criminalization and violence on the part of the authorities.

According to the ejidatarios, the current company has violated different clauses of the Collaboration and Consideration Agreement signed in 2019[1]. Faced with the imbalance of power to negotiate again, the ejidatarios initiated a blockade of the mine in September 2020.

Parota Dam, Guerrero

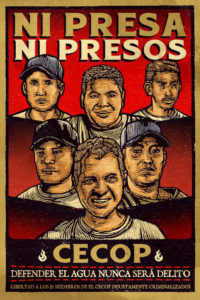

The Parota Dam project has existed for more than 30 years. In 2003, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE in its Spanish acronym) entered communal lands and began to carry out works without consulting or informing the campesinos about the effects[8]. It should be clarified that this project would imply changes in the use and ownership of the land, the relocation of several localities, the direct displacement of around 25,000 people and some 75,000 would be indirectly affected.

In 2003, the Council of Ejidatarios and Communities Opposing La Parota (CECOP) [9] was formed. Its resistance process to date has involved imprisonment, deaths and divisions. Given the lack of legal resources, they decided to fight to be recognized as comparable communities to appeal to the framework provided for indigenous peoples that, even with its limitations, offers some defense routes.

The resistance of CECOP, which has been accompanied by La Montaña Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center, has undergone multiple legal actions (allowing the order of temporary suspension of the works by different legal entities and on several occasions the release of prisoners). They continue to ask for the definitive cancellation. The current President has said that, at least during his tenure, he will not continue with this project[10].

Chicomuselo, Chiapas

Since 2008, the Canadian company BlackFire has tried to work in the municipality of Chicomuselo, Chiapas, for the creation of the largest barite mine in the world. Communities have opposed this project. The resistance, as in many cases, has come at a high cost to opponents, including the 2009 assassination of human rights defender Mariano Abarca[11].

Resistance through various actions such as demonstrations and complaints before federal and international authorities have allowed the mine to be temporarily closed. However, 12 mining concessions granted by the Mexican government to various companies, which have not been consulted with the affected communities, are still valid until the year 2059 the “Samuel Ruiz Garcia” Committee for the Promotion and Defense of Life denounced in 2017. In addition, harassment continues to be reported towards the population that rejects mining exploitation. It has also been reported that companies have taken advantage of the existing poverty to offer financial support and other incentives, which has caused divisions among the inhabitants.

In 2019, a federal judge in Canada admitted the possibility that Mariano Abarca “might not have been assassinated” if the Canadian Embassy in Mexico had “acted differently”, following the complaint that relatives of the defender filed with the Federal Court of Canada in Ottawa by act and omission in the mining conflict in 2008[12].

San Jose del Progreso, Oaxaca

The community of San Jose del Progreso opposes the operations of the Cuzcatlan mine, owned by the Canadian company Fortuna Silver Mines (FSM) since 2009[13]. The Coordinator of United peoples of Ocotlan Valley (COPUVO in its Spanish acronym) and the Magdalena Ocotlan Defense Committee against Mining were created, which are confronting the mining operation, something that has been increasingly dangerous and even deadly. In 2012, COPUVO defender, Vasquez Sanchez, was assassinated, a case that continues to go unpunished, after receiving threats from San Jose authorities and the Fortuna Silver Mines mining company, the same threats that were ignored by federal and state authorities.

The FSM mining company, through its subsidiary Cuzcatlan, has continued to operate in the region despite the fact that the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) has assured that it will not grant permission and despite the decision of the regional assemblies to declare that their territories will be free from mining. In July 2020, Cuzcatlan requested for the second time from SEMARNAT the authorization of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in its Regional modality (EIS-R San Jose II), in order to continue exploiting gold and silver for ten more years[14].

Variety of strategies in the absence of an established defense route

It is important to highlight the diversity of defense strategies that have been implemented with local, national and international components.

For example, there is the case of Union Hidalgo, Oaxaca, where the French transnational company Electricite De France (EDF Group), through its local Mexican subsidiaries, began to implement the “Gunaa Sicaru” wind project on indigenous Zapotec community land in 2015, without consulting or informing the community. France, being a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), is obliged to ensure that its companies respect human rights in other countries, so representatives of Union Hidalgo, together with the human rights organizations ProDESC and the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), filed a civil lawsuit in France in October 2020 denouncing violations of their rights by the French company[15].

In the case of Rio Sonora, Sonora, the worst mining environmental disaster in Mexico’s history happened, when, in August 2014, a Grupo Mexico mine, Buenavista del Cobre, spilled 40 million liters of acidified copper sulfate into the Sonora and Bacanuchi rivers, affecting more than 22 thousand people from seven municipalities. Almost seven years after the disaster, the promises of the Government and Grupo Mexico remain unfulfilled. Despite direct and indirect intimidation towards the affected people or opponents of business projects, the communities organized in the Rio Sonora Basin Committees with the support of national organizations for the defense of human rights, and the accompaniment of PODER, have demanded justice, remediation, reparation and non-repetition in front of national and international judicial mechanisms in the form of a strategic litigation[16].

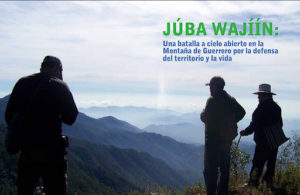

In the case of the Juba Wajiin community, Guerrero; in 2011, the indigenous Me Phaa began a community and regional struggle in defense of territory and life against the mining policy of the Mexican State, after the Federal Government granted two concessions on their territory, without having informed or consulted them. Faced with the environmental and social damage that open-pit mining would imply, the community decided to wage a fight and managed to obtain a historic ruling in 2016 in their favor that prevents mining companies from entering their territory for violating collective rights of indigenous peoples[17].

The cases highlighted in the text are just a few that exemplify how these processes use different defense strategies. They show challenges such as the double interest of the government, which, on the one hand, is responsible for guaranteeing human rights but, on the other, has its own economic interests or seeks to benefit companies as “development agents”. Furthermore, the main energy companies in Mexico are public.

It also shows how communities and defenders, after many years, continue to defend their rights and territories. What has often strengthened the defense has been the organization of the affected communities, forging alliances with others, with civil society and human rights defense organizations to be able to share tasks and exchange both experiences and information, said two members of PODER, part of the Focus Group of Civil Society on Business and Human Rights in Mexico, in an interview with SIPAZ.

Challenges and opportunities from the growing field of Business and Human Rights

“We must stop privileging business, competitiveness over human rights”

In the same interview, the members of PODER highlighted the global debate and the recognition that there is a responsibility of companies as a great advance, although it should be based more in Mexico. They expressed that many cases show the need for a binding treaty for public and private companies to make due diligence effective, to ensure that the rules that already exist are mandatory; and, in particular, to draft legislation that obliges companies to also respect human rights when they operate in third countries, even if the national legislative framework does not establish it.

The aforementioned international initiatives are positive, but a clearer demand mechanism is needed and little progress towards local implementation of the guiding principles has been observed during their ten years of existence[18].

Due to the power of companies, which is growing more and more, there is a serious risk that companies may have a greater interference in public policies, until they have the ability to “capture the State”, said Miguel Soto from PODER. In addition, in Mexico, there remains a major challenge in terms of access to justice and the right to reparation in general, said Ivette Gonzalez from PODER. Another challenge is being able to truly dialogue with companies so that they assume their responsibility and realize that, in the end, complying with it could be beneficial for them.

It is also worth mentioning that the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in the last year have led to greater difficulty in continuing with resistance processes, particularly those related to access to justice and reparation. This together with the limitations to be able to meet, demonstrate or organize events that are not exclusively digital. Meanwhile, megaprojects and extractivist companies have been able to continue their activity, being recognized as “essential activities.” [19] This makes the need and urgency of establishing one or more mechanisms that regulate the actions of companies even clearer, as well as a real and balanced debate on development models that are committed to the future.

Notes

- [1] Amnistía Internacional, 2021 EMPRESAS. Recuperado 28 de enero de 2021.

- [2]

SEGOB, 2020. Plan Nacional de Derechos Humanos 2019-2024. Recuperado 2 de febrero de 2021.

- [3] Observatorio de responsabilidad social corporativa. 2021 ¿Qué es RSC?. Recuperado 10 de febrero de 2021.

- [4] Centro de Información de Empresas y Derechos Humanos, 2021. Human Rights Defenders & Civic Freedoms. Recuperado 8 de febrero 2021.

- [5] TexasLawHelp, 2021. ¿Qué son las Demandas SLAPP?. Recuperado 5 de febrero 2021.

- [6] ONU- Oficina de alto comisionado de las Naciones Unidas. 2011. Principios Rectores sobre Empresas y Derechos Humanos. Rec. Recuperado 5 de febrero. 2021.

- [7] CIDSE. Together for global Justice. 2020. Nuevo documento: Una legislación de diligencia debida obligatoria de la UE para promover el respeto de las empresas por los derechos humanos y el medio ambiente Recuperado 18 de febrero 2021.

- [8] Rema

- [9] Rodolfo Chávez Galindo. El Conflicto Presa La Parota. Recuperado 18 de febrero 2021.

- [10] Tlachinollan Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Montaña. 2019. NOTA INFORMATIVA | 16 años del CECOP: hacia la construcción del tejido comunitario en los Bienes Comunales de Cacahuatepec. Recuperado 18 de febrero 2021.

- [11] El Proceso.2020. López Obrador descarta retomar proyecto de presa La Parota, en Guerrero. Recuperado 18 de febrero 2021.

- [12] Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina, 2021. Chicomuselo, Chiapas. Recuperado 16 de febrero 2021.

- [13] El País. 2019. Canadá se niega a investigar su actuación en la muerte de un activista mexicano. Recuperado 16 de febrero 2021.

- [14] Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina, 2021. Criminalizan protesta de habitantes de San José del Progreso por mina La Trinidad. Recuperado 16 de febrero 2021.

- [15]

ISTMO-Press. 2020. Denuncian a Minera Cuzcatlán-Fortuna Silver Mines (FSM) por contaminar pozos de agua en Oaxaca. Recuperado 17 de febrero 2021.

- [16] ProDESC. Unión Hidalgo se defiende de transnacional en Francia. Recuperado 12 de febrero 2021.

- [17] PODER.2021. Campaña Río Sonora. Por justicia, remediación, no repetición. Recuperado 12 de febrero 2021.

- [18] Tlachinollan Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Montaña. LA INCANSABLE LUCHA de Júba Wajiín por ser y vivir como hijas e hijos del fuego. Recuperado 12 de febrero 2021.

- [19] PODER. 2021. Entrevista con Miguel Soto y Ivette González. 11 de febrero 2021.

- [20] Centro de Información de Empresas y derechos humanos. 2021. México: Estudio del CIEDH revela violaciones de derechos humanos por parte de empresas durante la pandemia de Covid-19. Recuperado 15 de febrero 2021.

Other sources

- Comité Económico y Social Europeo 2020: INT/911 DICTAMEN Diligencia debida obligatoria, [Dictamen exploratorio]

- Informe: México: Empresas y Derechos Humanos. 2016. Compendio de información que presentan la Coalición de Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil al Grupo de Trabajo sobre Empresas y Derechos Humanos de la ONU

- COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS CIDH. 2019. Informe Empresas y Derechos Humanos: Estándares Interamericanos .

- SEGOB. 2020. Secretaria de Economía. INVERSIÓN EXTRANJERA DIRECTA EN MÉXICO Y EN EL MUNDO CARPETA DE INFORMACIÓN ESTADÍSTICA. Recuperado 8 de febrero 2021.