SPECIAL: 2024 Elections

30/06/2024

ARTICLE: Ecumenism and Networking, Paths of Hope for Chiapas

30/06/2024Working on the disappearance of people is entering the realms of the emptiness of the soul. Disappearance bursts into the course of a person’s life to alter it completely and definitively. For this reason, the organizations and people who work on this problem cannot address it without fully entering into the dimension of the heart, of everything that moves in the emotions and relationships of the people who are shaken by it.

Activities for our missing people within the framework of Mother’s Day, San Cristóbal de las Casas, May 2024 © SIPAZ

An Unstoppable Crisis

For some years now, various human rights organizations and groups of searching families have been documenting and denouncing the crisis of disappearances in Mexico. In 2023, people spoke with surprise about the alarming figure that had been reached: 100 thousand missing people; today there are more than 116 thousand.

According to an article from the Human Rights Program at the University of Minnesota, “the disappearance crisis has developed as part of a larger pattern of criminal violence in Mexico, driven by the activities of organized crime and the involvement, support or consent of state players in these criminal activities.” It also states that “even when the State is not directly involved with a disappearance, it has a positive responsibility to prevent and punish the perpetrators, as well as to search for the disappeared, which is why the context of impunity that exists in Mexico has contributed to the disappearance crisis.”

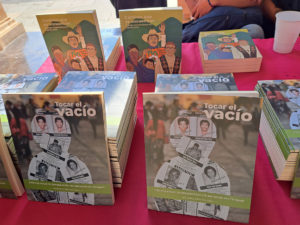

Touching the Void

Activities for our missing people within the framework of Mother’s Day, San Cristóbal de las Casas, May 2024 © SIPAZ

In April, the Working Group against Disappearance in Chiapas, consisting of the organizations Mesoamerican Voices, Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba), Services and Consultancy for Peace (SERAPAZ) and Melel Xojobal presented the report “Touching the Void”. It intends to do an x-ray of the situation of disappearance in Chiapas, about which they mention that “it is a historical problem that, currently, is going through an exponential increase derived, mainly, from a critical dispute for territorial control and social by organized crime.”

The National Registry of Missing and Unlocated Persons (RNPDNO) recorded a total of 68 missing and unlocated persons in Chiapas in 2019, 87 in 2020, 162 in 2021 and 244 in 2022. This indicates an increase of 358% between 2019 and 2022.

However, the report states that “beyond any official figure, from the documentation of the Working Group against Disappearances in Chiapas, we observe that this phenomenon has been increasing and the figure is, by far, higher than that reflected by any State body.”

The report talks about the crisis that is currently being experienced in the state due to the dispute over territorial control and the impact that this has on the crisis of disappearances. In this regard, it mentions that “this confrontation has left, to date, thousands of civilians in the middle of a war, under the constant threat of being victims of crimes, such as forced disappearance, related to homicides and femicides; forced recruitment; or human trafficking. The silencing of entire territories, added to state denialism and reductionism, prevents us from knowing the real dimensions of this situation. At least since June 2021, the Highlands region and the Border region stand out for the intensified violence caused by the dispute over territory between organized crime groups, and the diversity of armed players, who exercise population control based on threats, extortion and the disappearance of people.”

Another important point that is highlighted in this report is the diversity of situations and contexts in which disappearance occurs and how it differently affects the various populations that are victims of this crime. They speak of disappearance linked to territorial control of organized crime, to the context of political-electoral violence, or in the context of arbitrary arrests committed by state agents, among others. Regarding the victims, they mention the special vulnerability of people on the move, women, girls, boys and adolescents and human rights defenders.

In the case of the disappearance of women, and people belonging to sexual and gender diversity, “according to figures recovered by the UN Committee against Forced Disappearances (CED), after its visit to Mexico in 2021, Chiapas is one of the states where the disappearance of women far exceeds the national average of 25%, and reaches more than 60%, mostly affecting girls and adolescents between ten and 19 years old. According to what is documented, these cases would correspond to disappearances linked to the abduction of minors, to disappearances as a means to hide sexual violence and feminicide; to recruitment and reprisals. Disappearances that were aimed at trafficking and sexual exploitation were also reported.”

The report details that in our state there is a differentiation in the disappearance of women and men according to age range. While the majority of disappearances of men are concentrated between the ages of 25 and 44, in the case of women there are a greater number of disappearances of those who are between ten and 24 years old.

In the section on human rights defenders, the report states that “from 2019 to date, at least 46 cases of disappearance of defenders belonging to an indigenous people in Mexico have been recorded, many of them in retaliation for the territorial defense… in the majority of cases of homicide and disappearance, the hypotheses point mainly to organized crime groups, intertwined with economic and political power, for whom the defense of human rights represents an obstacle.”

Regarding people on the move, the Mesoamerican Voices organization points out that, of the total number of missing people in Mexico, at least 2,781 are foreigners, that is, transnational migrants, mainly Central Americans. Unfortunately, there is no real record of missing national migrants in Mexican territory. The report mentions that, in June 2010, national and international civil society organizations carried out a first survey, in the state of Chiapas, to make visible and give a statistical approach to the problem of disappearance of migrants, not only in transit, but also the local population that suffered disappearance on their migratory path. Over the course of ten months, it was possible to register 90 cases of disappearance of national migrants, mostly belonging to indigenous peoples. “In that context, the United Families Committee of Chiapas Looking for Our Migrants, Junax Ko´tantik (“Junax Ko´tantik” Committee) emerged, present to this day, demanding truth, justice, comprehensive reparation, non-repetition and collective memory”, the report states.

Regarding the disappearance of children and adolescents (NNA), the organization Melel Xojobal reports that Chiapas is in fourth place nationally in the disappearance of children and adolescents. In its own records, it recorded 2,144 cases of disappearances of children and adolescents as opposed to the 1,476 officially reported by the RNPDNO. They affirm that Tuxtla Gutierrez, Tapachula and San Cristobal de Las Casas concentrate the largest numbers, however, this last municipality has the highest rate of disappearance in the state, that is, it is the place where there is a greater risk of disappearance for children and adolescents. The report indicates that, of the total number of disappearances, 30% are of children and adolescents belonging to some indigenous people and the most common age is 15 years for men and women. It highlights that disappearance mainly affects girls and adolescent women who represent 70% of the cases. It also mentions that it is a phenomenon that has increased in the last two years and continues to grow.

As with Frayba regarding defenders and Mesoamerican Voices regarding people on the move, Melel denounces that “in the face of these alarming figures, we do not observe any interest on the part of the authorities to investigate the causes and patterns of the disappearance of children and adolescents in Chiapas.”

“Despite the different documentary difficulties such as the lack of reliable official information and the silencing of multiple territories where forced disappearance exists, we were able to say that in Chiapas there are various lines or patterns of disappearance of people, all of them denied, hidden and neglected by the Mexican State”, the report concludes.

Activities for our missing people within the framework of Mother’s Day, San Cristóbal de las Casas, May 2024 © SIPAZ

“I’ll swap my vote for my missing person”

On June 2nd, we witnessed the largest electoral process that Mexico has ever had. In this framework, groups of relatives of missing persons promoted the campaign “Vote for a missing person” through which they invited the population to place the name of one of the more than 116 thousand missing people in the space on the ballots designated for unregistered candidates.

This was done in order to make them visible and draw the attention of the authorities to their constant demand for justice. “We want them to look for them, it is their right. We want justice for our daughters even if they are not there. As a family, we deserve to have that peace that was taken from us,” explained relatives participating in this initiative.

According to the electoral authority, a vote is considered null when one of the boxes containing the name of the candidate or party of choice is not clearly marked or is completely crossed out or filled in with some slogan or demand.

On the other hand, ballots that contain the name of a person in the unregistered or independent candidacy box are considered valid: “the difference is that polling station officials are obliged to register the names of unregistered candidates, that is, the names of the missing people will appear in the official counts, making them visible,” according to what the campaign page explains.

On social networks, the campaign had a lot of traction and was shared with various slogans that emerged around it. “I’ll swap my vote for my missing person,” “#VotaXUnDesaparecidx” and “Vote with dignity” were some of these.

Election day was no different, social networks were filled with photographs of ballots with the names of missing people and messages like “Today I vote for the missing. There is no democracy without them.”, “I will swap my vote for my missing brother”, “Until we find them”, “Searching mothers are not a political campaign. Find your children!”, “Justice and truth”, “Ayotzinapa 43”, “Today I voted for you”, “Today my vote was for the disappeared of our Mexico” and “There is no democracy if they are not here!”, among others.

In Chiapas, searching mothers joined the campaign and also protested on several occasions at the Government Palace in Tuxtla Gutierrez, with banners, pink crosses and photographs of their relatives. They demanded that the candidates for the government of Chiapas pay attention to the problem of missing people in the state.

“We hope that the new government has empathy, that it is not indolent, that it welcomes the mothers, that we have the doors open in this Palace where we have been intimidated, rejected, violated and re-victimized by public servants. They must receive us with dignity. We want a fundamental change because corruption prevails here,” the mothers said.

Finally, according to data from the Preliminary Electoral Results Program (PERP) of the National Electoral Institute (INE), with 95% of the polls counted, more than one million 340 thousand people canceled their vote, of which 85 thousand 689 people voted for an unregistered candidate, of these, the “vote for a missing person” initiative counted that at least 3,511 of these were for missing people.

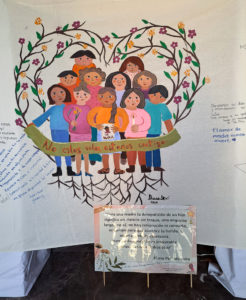

Facing Disappearance, We Sow Flowers of Hope

Another cry for attention from the relatives of missing people in Mexico occurs every May 10th, when groups of mothers of victims of disappearance and feminicide reaffirm that they have nothing to celebrate because their children have been taken from them.

On this occasion in Chiapas they did it through the “Flowers of Hope” event, through which they demanded that the authorities of the three levels of government search for their missing relatives.

“This action, called Flowers of Hope, responds to the simple reason that our lives today are dedicated to sowing hope in the midst of evil, corruption, hatred and the lack of interest on the part of the authorities in generating true change”, the Working Group against Disappearances in Chiapas said.

In their statement they mention: “the situation we are going through in Mexico and specifically in the state of Chiapas is complex, because on the one hand we have a growing wave of disappearances that is linked to unprecedented violence. And on the other hand, a silencing of reality, well planned and orchestrated by the authorities, who constantly deny the social and political crisis in the state.”

Therefore, “we sow flowers of hope with our daily actions of protest and denunciation, linking ourselves with other spaces and groups and networks that accompany families and searching mothers.”