LATEST: Mexico “happy, happy, happy”?

19/12/2019

ARTICLE: Civil Observation Mission in the Isthmus: Amplifying and connecting voices

19/12/2019“The absence of permanent spaces for dialogue between the State and indigenous peoples make the consultation of an investment project the only space where all the historical demands of indigenous peoples are addressed, and therefore this requirement for projects of investment is very important.” (6)

In the middle of the month of November of this year, the government of the “Fourth Transformation” convened the authorities and representative institutions of the municipalities and indigenous communities belonging to the indigenous Maya, Ch’ol, Tseltal, and Tsotsil, among other groups, from the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo, located in the area of the “Mayan Train Development Project”. The general public of these states was also invited to participate in the Indigenous Consultation process and Participatory Citizen Exercise Day, regarding the Mayan Train Project.

The indigenous consultation intends to establish a dialogue with approximately 3,400 indigenous communities, covering several phases and highlighting 15 regional assemblies, in order to receive their opinions and establish agreements regarding the participation of the peoples that are in the area of influence of the project, both in its implementation and in the “fair and equitable” distribution of benefits.

The project in the words of the government

According to official data, “the Mayan train is an integral project of territorial planning, infrastructure, economic growth, and sustainable tourism.” It aims to connect the main cities and tourist destinations in the five states of the Mexican peninsula in the southeast, through 1,460 km of railway and 18 train stations. The main objective stated is “the social welfare of the inhabitants of the Mayan Zone” through the potential generation of jobs, the economy growth of the area, and the development of infrastructure with basic services to improve the quality of life of the people of the region.

According to the government, “the Mayan Train implies the implementation of a new tourism paradigm that not only seeks to preserve local ecosystems, tourist sites, and cultures as much as possible, but will also generate a context that fosters the recognition and respect of native peoples and the ecology of the region; as well as integrating the population into the dynamics of economic growth.”

During the day, the railway will be used to transport local passengers and tourists, and at night to move cargo. “This will facilitate the commercial flow of local products to meet regional demand and optimize transportation costs.” The train is planned to be built in different phases and times; thus “during 2019, obsolete train tracks that go from Palenque to Valladolid will be rehabilitated, a section that represents half of the route. And in 2020 the construction of the sections of Selva and Caribe II will begin.” They plan to complete the project in four years and start its operation in 2024. (See Annex 1)

The project itself will have an investment of 120 billion pesos. The financing will be sourced by a mixed public-private model. When the government announced the project, they thought about 10% public financing, but in October of this year they announced that this figure will probably be around 40% of public money, leaving the rest for private investment (1).

In November of this year, the president affirmed that “at first it was planned to finance the construction of the Mayan Train through credits, but he clarified that thanks to the savings achieved by his administration in the first year of government, the work will be paid with the 2020 budget so as not to generate more debt to the country.”

The project is supported by the UN-Habitat and the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS). The Secretary of Commerce of the United States government, Wilbur Ross, reported that “they are willing to invest and help to build the Mayan Train and other infrastructure works in the southeast [of Mexico].”

Second consultation for the implementation of the project

The indigenous consultation process on the Mayan Train takes place one year after the first “general” or “citizen” consultation was carried out, in which 946,081 people participated and 89.9% voted in favor of the project. At the time, different communities, activists, organizations, and academics criticized the lack of a specifically indigenous consultation.

After this citizen consultation, on December 16, 2018, AMLO officially initiated the construction program when, through a Mayan ritual, AMLO requested permission from Mother Earth. For May 2019, the National Fund for Tourism Promotion (FONATUR in its Spanish acronym), published the bidding rules for the contracting of the basic engineering services of the train. The consortium composed of SENERMEX Engineering and Systems, Daniferrotools, Geotechnics, and Technical Supervision and Key Capital won, for an amount of just over 298 million pesos.

Subsequently, and on several occasions, the president spoke on the project presenting it as a fact. In September 2019, he expressed that “it is a work accepted by the majority of the inhabitants of the states of Yucatan, Tabasco, Chiapas, Campeche, and Quintana Roo, there is acceptance (2)”. During an event in Campeche, he mentioned that“hail, rain, or shine, kicking or shouting, the Mayan Train is going ahead because it is going ahead.”At other times, he stated the opposite: for example, in relation to the indigenous consultation, he said that “if people say no, we go there; the people rule.”

ILO Convention 169: Theoretical basis -but not practice- of indigenous consultation regarding the Mayan Train

Consultation process for the Constitutional and Legal Reform on the Rights of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican Peoples, San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, July 2018 © SIPAZ

Since announcing the Mayan Train plan, the director of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI in its Spanish acronym), Adelfo Regino, has repeatedly mentioned the importance of a prior, free, and informed consultation, in accordance with the terms of Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO). This Agreement on indigenous and tribal peoples was adopted by the International Labor Conference in 1989 and ratified by Mexico in 1990. It defines the consultation as a human right of collective ownership, with specific scope for indigenous peoples. There are also other laws and declarations, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that support such consultations.

All these texts imply that an indigenous consultation is a requirement for the Mexican government to initiate a megaproject, such as the Maya Train. In November 2019, Adelfo Regino once again pointed out that “the purpose of conducting a citizen consultation [read indigenous] to begin the construction of the Mayan Train is in order to comply with what is established in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) and to listen to the voice of the people (…) ILO Convention 169 establishes the duty to consult before legislative or administrative measures are made that have an impact on indigenous peoples and communities.”

A review of the “Protocol for the implementation of consultations to indigenous peoples and communities in accordance with the standards of Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries”, prepared by the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI in its Spanish acronym), now INPI, demonstrates that one of the basic conditions for an indigenous consultation is that the consultation be carried out prior to the start of the measures, authorizations, concessions, permits, or actions intended to promoted the project. That is, during the design of the project (3).

Challenges and criticisms of the consultations

Consultation process for the Constitutional and Legal Reform on the Rights of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican Peoples, San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, July 2018 © SIPAZ

Both in this case and in other projects proposed by the AMLO government, different sectors of civil society denounced that it seems as though “consultation processes are used to legitimize decisions already taken, without the participation of the affected peoples.”

We must take into account, as shown by an ILO regional report that “one of the main obstacles to the implementation of prior consultation in Latin America has been the high level of distrust between the parties that interact in these processes (States, indigenous, and private peoples), which hinders dialogue and the generation of agreements.” According to the report “both [the] State[s] and companies have been slow to understand that a consultation process, not only is to inform and propose compensation measures, but in many cases to make important changes to the investment project, finding ways to give indigenous peoples benefits. In turn, companies must understand that a prior consultation can also conclude that a given project is not suitable for the territory. Regarding the institutional aspects, it can be seen that the lack of consultation structures, official procedures, and teams trained to develop these processes also constitutes a great difficulty in developing consultation processes (4).”

In Mexico, indigenous consultations which have been conducted, such as the Program for the Development of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Trans-Isthmus Train), or the Consultation for Constitutional and Legal Reform on the Rights of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican Peoples, or the (yet to be carried out case of) the Maya Train, fall into the scope of the difficulties mentioned above.

For example, the organizations and communities that make up the Network of Community Defenders of the Peoples of Oaxaca (REDECOM in its Spanish acronym) and adherent organizations talked about an “express” consultation for the Tehuantepec Isthmus Development Program: “We believe that the urgency with which it is intended to be implemented prevents people and communities from properly informing us and using our own forms of community organization and agreement building, such as the Community Assembly,” they said.

Victoria Tauli-Corpus, UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, visits Chiapas, 2018 © Frayba

The Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining (REMA ion its Spanish acronym), stated that “the consultations are not informed, but manipulated. The imbalance in the power relationship starts with information control. The institutional media generates a social lynching in order to pressure the opponents of the project, it is generating divisions and violence where there were none and, in addition, the information that reaches the communities is insufficient, unintelligible, and without useful value so that communities can make good decisions.”(5)

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in her “Technical Note on Free Prior and Informed Consultation and Consent of Indigenous Peoples in Mexico” published in March 2019, called on the government to comply with the international standards of indigenous consultations regarding megaprojects in their territories. She stressed that “citizen consultation processes designed for the national population in general do not guarantee the safeguards of the rights of indigenous peoples enshrined in the international standards of rights of indigenous peoples”; Specific rights “that derive from the distinct character of the models and cultural histories of indigenous peoples, and because current democratic processes are usually not enough to meet the particular concerns of peoples, which are generally marginalized in the political sphere.”

In this regard, it is noteworthy that, along with the indigenous consultation on the Mayan Train, at the same time the general public is called to participate in a participatory citizen exercise, with the objective of “facilitating social consensus that contributes to maintain the conditions of unity and social cohesion, promote the strengthening of government institutions and democratic governance.” There is concern that the opinion of indigenous peoples remains as “minority” and therefore “expendable”.

Who should be consulted?

Convention 169 stipulates that indigenous peoples must be consulted through their representative institutions. Taking into account the characteristics of the country, the specificities of indigenous peoples and the subject and scope of the consultation, it is possible to determine which are the representative institutions. Depending on the circumstances, the appropriate institution may be representative at the national, regional, or community level; it can be part of a national network or it can represent a single community. An important criterion is that representativeness must be determined through a process of which the indigenous peoples themselves are part.

In this regard, there are also challenges posed in the ILO regional report, mentioned above. It indicates that according to different studies “indigenous organizations and their representatives are permanently questioned by their peers, which makes it difficult to establish lasting agreements.”

How should they be consulted and how will they be consulted?

Victoria Tauli-Corpus, UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, visits Chiapas, 2018 © Frayba

In the schedule of the Maya Train consultation process published by the government (see Annex 2), we can verify that, in comparison with the indigenous consultation or also called “Regional Consultative Assemblies on the creation of the Tehuantepec Isthmus Development Program” , the different stages of the consultation process are divided over the course of a month. One of the reasons why different organizations and communities spoke about an “express” consultation in Oaxaca, was because each assembly lasted only one day.

In one of his morning press conferences, the president noted that during the regional consultative assemblies, the population of Juchitan voted freehand in favor of the project in the Isthmus. According to the aforementioned, a consultation in accordance with Convention 169, will not seek a vote whose result is limited to “being in favor or being against.” Beyond this, the REMA noted that “the consultations do not include ‘binding consent’. The decision of the community does not determine the future of the project, because consultation is an administrative requirement that requires its exercise for projects that are already at very advanced stages in the generation of interests.”

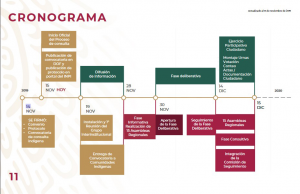

Officially, the consultation on the Maya train began on November 15th, with an “informative stage.” On November 29 and 30, 15 Regional Information Assemblies will be held before declaring the deliberative phase open in which meetings or assemblies may be held in the communities to reflect on the information received and build proposals, suggestions, or approaches regarding the project.

Subsequently, 15 Regional Consultative Assemblies will be held on December 14 and 15 of this year to receive these suggestions or approaches, which may also be received by email or directly at INPI facilities.

Unlike the previous one, the indigenous consultation on the Mayan Train is a little closer to what is established in Convention 169 on the appropriate procedures that the government “must give enough time to indigenous peoples to organize their own processes of decision making and participate effectively in decisions made in a manner consistent with their cultural and social traditions.”

However, “in terms of consent with full information, (the consultation) could be achieved hypothetically, but knowing how the processes are regarding worldviews and community processes, I do not see it feasible to do so in such a short time. That is, it is possible, but not feasible,” said the former head of the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP in its Spanish acronym), Ernesto Enkerlin Hoeflich, in an interview with El Universal newspaper.

Mayan Train: A green and sustainable project?

Another legal requirement that must be met is the Environmental Impact Authorization (AIA in its Spanish acronym). The Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA in its Spanish acronym) reported that, “any project of this type requires authorization in matters of environmental impact by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT in its Spanish acronym). In the case of railways, an Environmental Impact Manifestation (EIM) must be submitted in regional modality. ”As far as the Mayan Train is concerned, these requirements have also not been fully met (6), which is worrying and will hardly be taken before the indigenous consultation as an element to be taken into account. It is also paradoxical, when the project proposes to look for “green development”, in and/or near several Protected Natural Areas (PNAs).

However, different academics have published environmental impact studies, including a study on the impact on the Calakmul and Balam-ku PNAs in Campeche. They concluded that “both the construction of the Mayan Train, as well as the urban-tourist development proposed by FONATUR, will cause negative effects on the ecological functions of the PNAs of Calakmul and Balam-ku (…) the trends of habitat loss and fragmentation, and it will also cause barrier (blocking and running over) and edge (noise and vibration) effects”(7).

The government has announced that “they will use existing rights of way, respect environmental reserves,” which will build wildlife passages and protect biological corridors (8).

These mitigation methods are also mentioned in the same study of academics, however they affirm that “despite the implementation of these measures, there are critical points in the Los Laureles-Constitucion section, such as the cave of bats, whose deterioration is not compensable with conventional mitigation measures. In addition, the main ecological function of the PNAs in this section, which consists in giving continuity to the flora and fauna of the region, is incompatible with the current design of the urban-tourism project.”

In the Calakmul Biosphere Reserves, and others such as Sian ka’an and the Petenes, “it is forbidden to change land use, establish new population centers, and carry out development projects, since its main purpose is conservation of its environmental characteristics,” says Cemda.

South-Southeast Territorial Reorganization Project

The Mayan Train project is related to the Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life) program, but not only for the repair of environmental damage through reforestation. AMLO explained that the Mayan Train, the Trans-Isthmus corridor, and Sowing Life among other “regional development projects” will serve as “curtains” to “capture the migratory flow in its transit” to the United States and “anchor those fleeing poverty” in these regions.

The Mayan Train, according to Geocomunes researchers, is a “much broader and more complex project: The South-Southeast Territorial Reorganization Project. It is a large regional project consisting of various other initiatives (among which are the Mayan Train, Sowing Life, Special Economic Zones (SEZ), and the Trans-Isthmus corridor), towards a long-term and still unfinished objective: the control, distribution, and neoliberal instrumentalization of territories and peoples of the peninsula (9).”This broader project can be very abstract for the indigenous communities consulted on the Mayan train if they are offered this information.

Tourism project as development?

According to the 2018-2024 Nation Project of the Morena party, “the archaeological sites of Mayan culture and the surrounding communities must be integrated into national development to better conserve and improve the competitiveness of our tourism offer.”

FONATUR reported in October of this year through the newspaper Reforma that the launch of the Fiber (See Annex 3) of the Maya Train will be delayed, due to difficulties in negotiations with ejidatarios when six of the 18 trusts were formed in the planned stations: Escarcega, Campeche; Izamal and Valladolid in Yucatan; Coba, Quintana Roo; and Palenque, Chiapas. Note that these agreements were achieved before a formal indigenous consultation.

Although there are different declarations by public officials in this regard, the increase in visitor flows is expected to be exponential. Beyond development, what this will mean for the communities and the affected population should be reviewed.

Inhabitants of the area have declared, referring with fear to what happened in other tourist centers such as Cancun, where, according to an interview from Animal Politico, “the Mayan people have only obtained bad jobs, after losing their lands. For them poverty and inequality followed. The areas have become the focus of violence and tourism has brought problems such as drug trafficking and human trafficking.”

Horizons

There are serious doubts about the appropriate consultation processes in a project such as the Mayan Train. Clearly, the stages prior to the ongoing consultation failed to respect several laws, treaties, and conventions ratified by Mexico in order to recognize and protect its indigenous peoples. The fact that the government has not yet met the other requirements, including an environmental or market impact study, is particularly worrying when the information stage is already in progress. It is also feared that the income generated will not be left to the communities themselves. It could also generate more divisions in the already injured indigenous communities both during the same consultation process and when the project is carried out, with resources that benefit some more than others, breaking down the values of communality and solidarity. These are some things to consider when deciding whether or not to endorse the project.

- Regional report: Convention No. 169 of the ILO, on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries [Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Chile] and prior consultation of indigenous peoples in investment projects

- The Fourth Transformation reached all the communities of Yucatan, says President Lopez Obrador in Merida

- Protocol for the implementation of consultations with indigenous peoples and communities in accordance with the standards of Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries

- Regional report: Convention No. 169 of the ILO, on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries [Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Chile] and prior consultation of indigenous peoples in investment projects

- COMUNICADO | LAS CONSULTAS “BUENAS” NO EXISTEN “BASTA DE ENGAÑAR A LOS PUEBLOS”

- INVITACIÓN A CUANDO MENOS TRES PERSONAS NACIONAL MIXTA NO. TMFON-EA/19-S-01

- Impact of the Railroad and Tourism Growth Associated with the Mayan Train; mitigation measures and design changes for the Calakmul and Balam-kú reserves

- Consultation processes for the Mayan Train

- The Mayan Train. A new territorial linkage project in the Yucatan Peninsula